Movers & Shakers in American Ceramics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

European Art & Decorative Arts Wall Text and Extended Labels

European Art & Decorative Arts Wall Text and Extended Labels FIRST FLOOR The Morgan Memorial The construction of the Morgan Memorial, completed in two sections in 1910 and 1915, more than doubled the size of the original Wadsworth Atheneum that opened in 1844. The building is dedicated to Junius Spencer Morgan, whose bust by William Wetmore Story stands at the top of the western stairs. Morgan was a Hartford man who founded a banking empire, and his son, J. Pierpont Morgan, chose to build the museum’s new wing as a tribute to his father. The total cost of the Memorial—over $1,400,000—represents the largest of J. Pierpont Morgan’s generous gifts. He spent over twelve years purchasing the several properties on which the Memorial stands, and was involved in its construction until his death in 1913. Benjamin Wistar Morris, a noted New York architect, was selected to design what was to be a new home for the Wadsworth Atheneum’s art collection. It was built in the grand English Renaissance style, and finished with magnificent interior details. Four years after J. Pierpont Morgan’s death, his son, J. Pierpont Morgan Jr., followed the wishes outlined in his father’s will and gave the Wadsworth Atheneum a trove of ancient art and European decorative arts from his father’s renowned collection. Living in the Ancient World Ordinary objects found at sites from the countries surrounding the Mediterranean Sea and the Middle East reveal a great deal about daily life in the ancient world. Utensils for eating and drinking, glassware, lamps, jewelry, pottery, and stone vessels disclose the details of everyday life. -

Philippa H Deeley Ltd Catalogue 17 Oct 2015

Philippa H Deeley Ltd Catalogue 17 Oct 2015 1 A Pinxton porcelain teapot decorated in gilt with yellow cartouches with gilt decoration and hand hand painted landscapes of castle ruins within a painted botanical studies of pink roses, numbered square border, unmarked, pattern number 300, 3824 in gilt, and three other porcelain teacups and illustrated in Michael Bertould and Philip Miller's saucers from the same factory; Etruscan shape 'An Anthology of British Teapots', page 184, plate with serpent handle, hand painted with pink roses 1102, 17.5cm high x 26cm across - Part of a and gilt decoration, the saucer numbered 3785 in private owner collection £80.00 - £120.00 gilt, old English shape, decorated in cobalt blue 2 A Pinxton porcelain teacup and saucer, each with hand painted panels depicting birds with floral decorated with floral sprigs and hand painted gilt decoration and borders, numbered 4037 in gilt landscapes with in ornate gilt surround, unmarked, and second bell shape, decorated with a cobalt pattern no. 221, teacup 6cm high, saucer 14.7cm blue ground, gilt detail and hand painted diameter - Part of a private owner collection £30.00 landscape panels - Part of a private owner - £40.00 collection £20.00 - £30.00 3 A porcelain teapot and cream jug, possibly by 8A Three volumes by Michael Berthoud FRICS FSVA: Ridgway, with ornate gilding, cobalt blue body and 'H & R Daniel 1822-1846', 'A Copendium of British cartouches containing hand painted floral sparys, Teacups' and 'An Anthology of British Teapots' co 26cm long, 15cm high - -

Annual Report 2013-2014

The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston Arts, Fine of Museum The μ˙ μ˙ μ˙ The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston annual report 2013–2014 THE MUSEUM OF FINE ARTS, HOUSTON, WARMLY THANKS THE 1,183 DOCENTS, VOLUNTEERS, AND MEMBERS OF THE MUSEUM’S GUILD FOR THEIR EXTRAORDINARY DEDICATION AND COMMITMENT. ANNUAL REPORT ANNUAL 2013–2014 Cover: GIUSEPPE PENONE Italian, born 1947 Albero folgorato (Thunderstuck Tree), 2012 Bronze with gold leaf 433 1/16 x 96 3/4 x 79 in. (1100 x 245.7 x 200.7 cm) Museum purchase funded by the Caroline Wiess Law Accessions Endowment Fund 2014.728 While arboreal imagery has dominated Giuseppe Penone’s sculptures across his career, monumental bronzes of storm- blasted trees have only recently appeared as major themes in his work. Albero folgorato (Thunderstuck Tree), 2012, is the culmination of this series. Cast in bronze from a willow that had been struck by lightning, it both captures a moment in time and stands fixed as a profoundly evocative and timeless monument. ALG Opposite: LYONEL FEININGER American, 1871–1956 Self-Portrait, 1915 Oil on canvas 39 1/2 x 31 1/2 in. (100.3 x 80 cm) Museum purchase funded by the Caroline Wiess Law Accessions Endowment Fund 2014.756 Lyonel Feininger’s 1915 self-portrait unites the psychological urgency of German Expressionism with the formal structures of Cubism to reveal the artist’s profound isolation as a man in self-imposed exile, an American of German descent, who found himself an alien enemy living in Germany at the outbreak of World War I. -

Q (Q § « ^ O.2 E (9 •G 0 § ^ 0 22 May—13 September 1964 S Trustees of the American Craftsmen's Councii Mrs

»he Museum of Contemporary Crafts, 29 West 53rd Street, New York Q (Q § « ^ o.2 e (9 •g 0 § ^ 0 22 May—13 September 1964 s Trustees of the American Craftsmen's Councii Mrs. Vanderbilt Webb, Chairman of the Board Kenneth Chorley, Vice-Chairman William J. Barrett, President and, Treasurer May E. Walter, Secretary Mrs. 8. D. Adams Alfred Auerbach Thomas D'Arcy Brophy Rene d'Harnoncourt Mark EIIingson Mrs. John Houseman Bernard Kester Walter H. Kilham, Jr. V. Lada-Mocarski Jack Lenor Larsen Dorothy Liebes Harvey K. Littleton Francis S. Merritt Forrest D. Murden, Jr. Mary S. Nelson De Witt Peterkin, Jr. Frank Stanton John B. Stevens Mrs. R. Peter Straus Edward Worm ley Museum Staff Paul J. Smith, Director Sybil Frank Marion Lehane Robert Nunnelley Ben E. Watkins An introduction to THE AMERICAN CRAFTSMAN In assembling this exhibition, emphasis was given to representing the wide range of work being done today by America •: ::";: ftsmen—from the strictly utilitarian object to the non-functional work of fine art, from use in personal adornment to application in architectural setting, from devotion t<^ traditional means of work- ing to experimentation with new fabrication pro: .. -rom creation of unique pieces to design application in industrial production. The thirty craftsmen rep- resented, chosen from the hundreds of craftsmen of equal stature, are from every section of the country, of all ages, with every type of background and a wide variety of training. In illustrating the diversity of the work of the American craftsmen no attempt has been made, however, to explain this diversity in terms of geographical areas; cultural influences, or mingling of various art forms. -

Ceramics Monthly Jan86 Cei01

William C. Hunt........................................ Editor Barbara Tipton ...................... Associate Editor Robert L. Creager ........................ Art Director Ruth C. Butler............................. Copy Editor Valentina Rojo ...................... Editorial Assistant Mary Rushley................ Circulation Manager Mary E. Beaver. Circulation Assistant Jayne Lohr .................... Circulation Assistant Connie Belcher .... Advertising Manager Spencer L. Davis.............................. Publisher Editorial, Advertising and Circulation Offices 1609 Northwest Boulevard Box 12448, Columbus, Ohio 43212 (614) 488-8236 Ceramics Monthly (ISSN 0009-0329) is published monthly except July and August by Professional Publications, Inc.—S. L. Davis, Pres.; P. S. Emery, Sec.: 1609 North west Blvd., Columbus, Ohio 43212. Second Class postage paid at Columbus, Ohio. Subscription Rates:One year SI8, two years $34, three years $45. Add $5 per year for subscriptions outside the U.S.A. Change of Address:Please give us four weeks advance notice. Send both the magazine wrapper label and your new address to: Ceramics Monthly, Circulation Office, Box 12448, Columbus, Ohio 43212. Contributors: Manuscripts, photographs, color separations, color transparencies (in cluding 35mm slides), graphic illustrations, texts and news releases dealing with ceramic art and craft are welcome and will be con sidered for publication. A booklet describing procedures for the preparation and submis sion of a manuscript is available upon re quest. Send manuscripts and correspondence about them to: Ceramics Monthly, The Ed itor, Box 12448, Columbus, Ohio 43212. Telecommunications and Disk Media: Ceramics Monthly accepts articles and other data by modem. Phone us for transmission specifics. Articles may also be submitted on 3.5-inch microdiskettes readable with an Ap ple Macintosh computer system. Indexing:Articles in each issue of Ceramics Monthly are indexed in the Art Index. -

Glasunternehmen Vista Alegre Atlantis Group Und Glaswerk IVIMA, Portugal

Pressglas-Korrespondenz 2006-2 Dieter Neumann, Ralph Sadler, SG März 2006 Glasunternehmen Vista Alegre Atlantis Group und Glaswerk IVIMA, Portugal Guten Tag Herr Neumann, tons per day in 1974, and therefore creating opportuni- ties in new markets. The Atlantis crystal was by then die Firma IVIMA ist unseres Wissens 1998 von der being exported to 20 different countries and has become "Grupo Atlantis" gekauft worden. (siehe unten) famous as one of the purest crystals in the world. Die Website ist folgende: During that same year, 1974, the glass factory in Ma- http://www.atlantis-cristais-de- rinha Grande was converted to produce automatic- alcobaca.pt/ivima/pt/flash/en/index.html made glass in Portugal, which is nowadays, commer- Anschrift und Ansprechpartner finden Sie unter: cialized under the name CRISAL GLASS. http://www.atlantis-cristais-de- In 1985 Atlantis decided do build a new factory to pro- alcobaca.pt/ivima/pt/flash/en/contactos.html. duce 10 tons of crystal per day, and moved to Casal da Mit freundlichen Grüßen, Areia, also in Alcobaça. In 1986 the company was listed António Teixeira on the Lisbon Stock Exchange. [email protected] In 1991 the production capacity of the Marinha Gran- Tauentzienstrasse 7 b/c – 10789 Berlin de factory was increased to 50 tons/day. Tel. +49 30 254106 15, Fax +49 30 254106 99 http://www.portugalinbusiness.com http://www.visitportugal.com http://www.atlantis-cristais-de- alcobaca.pt/ivima/pt/flash/en/historia.html In 1972 the factory was converted to produce top quali- ty handmade lead crystal - the Atlantis crystal, which was launched on the American market that same year. -

Process & Presence

ProCeSS & PreSenCe: Selections from the Museum of Contemporary Craft March 15-July 4, 2011 hroughout history, hand skills Most inDiviDuals now learn craft processes and the ability to make things have been in academic environments, rather than within necessary for human survival. Before the the embracing context of ethnic or other cultural advent of industrial mechanization and traditions. The importance of individual expression the dawn of the digital age, all members of and experimentation has caused the contemporary Tany given community were craftspeople. Everything craft world to come alive with innovation and ever- that was necessary for life—clothing, tools and home changing interpretations of traditional styles, objects furnishings—was made by hand. In America, diverse and techniques. In recent years, the hallowed and populations—Native peoples, immigrant groups and often contentious ideological separation of fine art and regional populations—have preserved and shared craft has begun to ease. Some craft artists have been ancient and evolving traditions of making functional embraced by the fine art community and included in objects for everyday use. the academic canon. Many colleges and universities During the twentieth century, the mass now incorporate crafts education into their overall arts production of utilitarian wares removed the need for curricula and work by studio craft artists routinely functional handmade objects from modern society. appears in art galleries and art museums. This ultimately gave rise to the studio craft movement. PortlanD’s MuseuM of contemporary craft Unlike traditional crafts, studio crafts include visual has long been an important proponent of the studio values as a primary function of creative expression. -

Antonio Prieto; » Julio Aè Pared 30 a Craftsman5 Ipko^Otonmh^

Until you see and feel Troy Weaving Yarns . you'll find it hard to believe you can buy such quality, beauty and variety at such low prices. So please send for your sample collection today. and Textile Company $ 1.00 brings you a generous selection of the latest and loveliest Troy quality controlled yarns. You'll find new 603 Mineral Spring Avenue, Pawtucket, R. I. 02860 pleasure and achieve more beautiful results when you weave with Troy yarns. »««Él Mm m^mmrn IS Dialogue .n a « 23 Antonio Prieto; » Julio Aè Pared 30 A Craftsman5 ipKO^OtONMH^ IS«« MI 5-up^jf à^stoneware "iactogram" vv.i is a pòìnt of discussion in Fred-Schwartz's &. Countercues A SHOPPING CENTER FOR JEWELRY CRAFTSMEN at your fingertips! complete catalog of... TOOLS AND SUPPLIES We've spent one year working, compiling and publishing our new 244-page Catalog 1065 ... now it is available. In the fall of 1965, the Poor People's Corporation, a project of the We're mighty proud of this new one... because we've incor- SNCC (Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee), sought skilled porated brand new never-before sections on casting equipment, volunteer craftsmen for training programs in the South. At that electroplating equipment and precious metals... time, the idea behind the program was to train local people so that they could organize cooperative workshops or industries that We spent literally months redesigning the metals section . would help give them economic self-sufficiency. giving it clarity ... yet making it concise and with lots of Today, PPC provides financial and technical assistance to fifteen information.. -

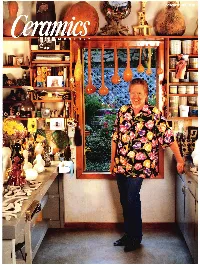

Adrian Saxe by Elaine Levin

October 1993 1 William Hunt.................................... Editor Ruth C. Butler ................Associate Editor Robert L. Creager..................... Art Director Kim Nagorski..... .............Assistant Editor Mary Rushley ............... Circulation Manager Mary E. Beaver ....Assistant Circulation Manager Connie Belcher .......Advertising Manager Spencer L. Davis .......................... Publisher Editorial, Advertising and Circulation Offices 1609 Northwest Boulevard Post Office Box 12448 Columbus, Ohio 43212 (614) 488-8236 FAX (614) 488-4561 Ceramics Monthly (ISSN 0009-0328) is pub lished monthly except July and August by Profes sional Publications, Inc., 1609 Northwest Bou levard, Columbus, Ohio 43212. Second Class postage paid at Columbus, Ohio. Subscription Rates: One year $22, two years $40, three years $55. Add $10 per year for subscriptions outside the U.S.A. In Canada, also add GST (registration number R123994618). Change of Address:Please give us four weeks advance notice. Send the magazine address label as well as your new address to: Ceramics Monthly, Circulation Offices, Post Office Box 12448, Columbus, Ohio 43212. Contributors: Manuscripts, announcements, news releases, photographs, color separations, color transparencies (including 35mm slides), graphic illustrations and digital TIFF or EPS im ages are welcome and will be considered for publication. Mail submissions to Ceramics Monthly, Post Office Box 12448, Columbus, Ohio 43212. We also accept unillustrated mate rials faxed to (614) 488-4561. Writing and Photographic Guidelines:A book let describing standards and procedures for sub mitting materials is available upon request. Indexing:An index of each year’s articles appears in the December issue. Additionally, Ceramics Monthly articles are indexed in the Art Index. Printed, on-line and CD-ROM (computer) index ing is available through Wilsonline, 950 Univer sity Avenue, Bronx, New York 10452; and from Information Access Company, 362 Lakeside Drive, Forest City, California 94404. -

Postmodernism

Black POSTMODERNISM STYLE AND SUBVERSION, 1970–1990 TJ254-3-2011 IMUK VLX0270 Postmodernism W:247mmXH:287mm 175L 130 Stora Enso M/A Magenta(V) 130 Stora Enso M/A 175L IMUK VLX0270 Postmodernism W:247mmXH:287mm TJ254-3-2011 1 Black Black POSTMODERNISM STYLE AND SUBVERSION, 1970–1990 TJ254-3-2011 IMUK VLX0270 Postmodernism W:247mmXH:287mm 175L 130 Stora Enso M/A Magenta(V) 130 Stora Enso M/A 175L IMUK VLX0270 Postmodernism W:247mmXH:287mm TJ254-3-2011 Edited by Glenn Adamson and Jane Pavitt V&A Publishing TJ254-3-2011 IMUK VLX0270 Postmodernism W:247mmXH:287mm 175L 130 Stora Enso M/A Magenta(V) 130 Stora Enso M/A 175L IMUK VLX0270 Postmodernism W:247mmXH:287mm TJ254-3-2011 2 3 Black Black Exhibition supporters Published to accompany the exhibition Postmodernism: Style and Subversion, 1970 –1990 Founded in 1976, the Friends of the V&A encourage, foster, at the Victoria and Albert Museum, London assist and promote the charitable work and activities of 24 September 2011 – 15 January 2012 the Victoria and Albert Museum. Our constantly growing membership now numbers 27,000, and we are delighted that the success of the Friends has enabled us to support First published by V&A Publishing, 2011 Postmodernism: Style and Subversion, 1970–1990. Victoria and Albert Museum South Kensington Lady Vaizey of Greenwich CBE London SW7 2RL Chairman of the Friends of the V&A www.vandabooks.com Distributed in North America by Harry N. Abrams Inc., New York The exhibition is also supported by © The Board of Trustees of the Victoria and Albert Museum, 2011 The moral right of the authors has been asserted. -

Gareth Mason: the Attraction of Opposites Focus the Culture of Clay

focus MONTHLY the culture of clay of culture the Gareth Mason: The Attraction of Opposites focus the culture of clay NOVEMBER 2008 $7.50 (Can$9) www.ceramicsmonthly.org Ceramics Monthly November 2008 1 MONTHLY Publisher Charles Spahr Editorial The [email protected] telephone: (614) 794-5895 fax: (614) 891-8960 editor Sherman Hall assistant editor Brandy Wolfe Ceramic assistant editor Jessica Knapp technical editor Dave Finkelnburg online editor Jennifer Poellot Harnetty editorial assistant Holly Goring Advertising/Classifieds Arts [email protected] telephone: (614) 794-5834 fax: (614) 891-8960 classifi[email protected] telephone: (614) 794-5843 advertising manager Mona Thiel Handbook Only advertising services Jan Moloney Marketing telephone: (614) 794-5809 marketing manager Steve Hecker Series $29.95 each Subscriptions/Circulation customer service: (800) 342-3594 [email protected] Design/Production Electric Firing: Glazes & Glazing: production editor Cynthia Griffith design Paula John Creative Techniques Finishing Techniques Editorial and advertising offices 600 Cleveland Ave., Suite 210 Westerville, Ohio 43082 Editorial Advisory Board Linda Arbuckle; Professor, Ceramics, Univ. of Florida Scott Bennett; Sculptor, Birmingham, Alabama Tom Coleman; Studio Potter, Nevada Val Cushing; Studio Potter, New York Dick Lehman; Studio Potter, Indiana Meira Mathison; Director, Metchosin Art School, Canada Bernard Pucker; Director, Pucker Gallery, Boston Phil Rogers; Potter and Author, Wales Jan Schachter; Potter, California Mark Shapiro; Worthington, Massachusetts Susan York; Santa Fe, New Mexico Ceramics Monthly (ISSN 0009-0328) is published monthly, except July and August, by Ceramic Publications Company; a Surface Decoration: Extruder, Mold & Tile: subsidiary of The American Ceramic Society, 600 Cleveland Ave., Suite 210, Westerville, Ohio 43082; www.ceramics.org. -

Kate Maury, in an Architectural Context Clay Culture: Pacifi C Standard Time Mr

Cover: Kate Maury, in an Architectural Context Clay Culture: Pacifi c Standard Time Mr. Bailey’s Museum of Wonders Spotlight: Clay at Otis “My Brent CXC is 24 years old and still handles all the clay I can pile on and has never had to be repaired! I don’t expect to ever have to replace it.” George McCauley Photo: Tom Ferris brentwheels.com The Beauty & Magic of the Shino Carbon Trap Lou Raye Nichol My work focuses on carbon trapped porcelain. When I first saw the accidental results it produces, I was enthralled. There is a magic in opening a kiln full of surprises. The beauty of the effects created by this method can be breathtaking. Their unpredictability can be humbling – pots that I thought of as throw-away have turned out to be the most successful. I had to change the way I make pots because of the complexity of the glazes. With Shino Carbon Trap glazes, I am always push- ing to see how much is too much. I chose a Bailey gas kiln because it was highly recom- mended at the shino carbon trap workshops I had attended. Our teacher fired all his shinos in a Bailey. I had never fired a gas kiln on my own when I started, so this was a great leap for me. With significant support from the Bailey team, I have become comfortable managing such sensitive firings. Their responsiveness to my technical questions, and interest in my results has been invaluable. This is a great kiln, and my firing results confirm that I made the right choice.