Download Article

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Human Remains, Museum Space and the 'Poetics of Exhibiting'

23 — VOLUME 10 2018 UNIVERSITY MUSEUMS AND COLLECTIONS JOURNAL Human remains, museum space and the ‘poetics of exhibiting’ Kali Tzortzi Abstract The paper explores the role of the design of museum space in the chal- lenges set by the display of human remains. Against the background of ‘embodied understanding’, ‘multisensory learning’ and ‘affective distance’ and of contextual case studies, it analyses the innovative spa- tial approach of the Moesgaard Museum of the University of Aarhus, which, it argues, humanizes bog bodies and renders them an integra- tive part of an experiential, embodied and sensory narrative. This allows the mapping of spatial shifts and new forms of engagement with human remains, and also demonstrates the role of university museums as spaces for innovation and experimentation. 24 — VOLUME 10 2018 UNIVERSITY MUSEUMS AND COLLECTIONS JOURNAL Introduction and research question This paper aims to explore the issue of the respectful presentation of human physical remains in contextual exhibitions by looking at the role of museum space in the challenges set by their display, with particular reference to the contribution of experimentation in the university museum environ- ment. The debate raised by the understanding that human remains “are not just another artefact” (stated by CASSMAN et al. 2007, in GIESEN 2013, 1) is extensively discussed in the literature, and increasingly explored through a range of museum practices. In terms of theoretical understanding, authors have sought to acquire an overall picture of approaches towards the care of human remains so as to better understand the challenges raised. For example, among the most recent publica- tions, O’Donnabhain and Lozada (2014) examine the global diversity of attitudes to archaeological human remains and the variety of approaches to their study and curation in different countries. -

The Early Bryologists of South West Yorkshire

THE EARLY BRYOLOGISTS OF SOUTH WEST YORKSHIRE by Tom Blockeel [Bulletin of the British Bryological Society, 38, 38-48 (July 1981)] This account brings together information which I have encountered during work on the bryology of South West Yorkshire (v.-c. 63). It lays no claim to originality, but is rather a collation of biographical data from disparate sources, and is presented here in the hope that it may be of interest to readers. I have confined myself largely to those botanists of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries who made significant contributions to the bryology of v.-c. 63. If there are any omissions or other deficiencies, I should be grateful to hear of them, and of any additional information which readers may have to hand. The Parish of Halifax has been a centre of bryological tradition for over two hundred years. It was there that there appeared, in 1775, the first contribution of substance to South Yorkshire bryology, in the form of an anonymous catalogue of plants published as an appendix to the Rev. J. Watson’s History and Antiquities of the Parish of Halifax. Traditionally, the catalogue was attributed to James Bolton (d. 1799) of Stannary, near Halifax, whose life was researched by Charles Crossland at the beginning of this century (Crump & Crossland, 1904; Crossland, 1908, 1910). Bolton was the author of fine illustrated botanical works, notably Filices Britannicae and the History of Fungusses growing about Halifax, the latter being the first British work exclusively devoted to fungi. However, his work extended beyond the purely botanical. Shortly after the completion of the History of Fungusses, which was dedicated to and sponsored by Henry, the sixth earl of Gainsborough, Bolton wrote to his friend John Ingham: ‘You must know, John, that I have been so long tilted between roses and toadstools, and back again from toadstools to roses, that I am wearied out with both for the present, and wish (by way of recreation only) to turn for awhile to some other page in the great volume. -

Dynamics of Religious Ritual: Migration and Adaptation in Early Medieval Britain

Dynamics of Religious Ritual: Migration and Adaptation in Early Medieval Britain A Dissertation SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Brooke Elizabeth Creager IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Peter S. Wells August 2019 Brooke Elizabeth Creager 2019 © For my Mom, I could never have done this without you. And for my Grandfather, thank you for showing me the world and never letting me doubt I can do anything. Thank you. i Abstract: How do migrations impact religious practice? In early Anglo-Saxon England, the practice of post-Roman Christianity adapted after the Anglo-Saxon migration. The contemporary texts all agree that Christianity continued to be practiced into the fifth and sixth centuries but the archaeological record reflects a predominantly Anglo-Saxon culture. My research compiles the evidence for post-Roman Christian practice on the east coast of England from cemeteries and Roman churches to determine the extent of religious change after the migration. Using the case study of post-Roman religion, the themes religion, migration, and the role of the individual are used to determine how a minority religion is practiced during periods of change within a new culturally dominant society. ii Table of Contents Abstract …………………………………………………………………………………...ii List of Figures ……………………………………………………………………………iv Preface …………………………………………………………………………………….1 I. Religion 1. Archaeological Theory of Religion ...………………………………………………...3 II. Migration 2. Migration Theory and the Anglo-Saxon Migration ...……………………………….42 3. Continental Ritual Practice before the Migration, 100 BC – AD 400 ………………91 III. Southeastern England, before, during and after the Migration 4. Contemporary Accounts of Religion in the Fifth and Sixth Centuries……………..116 5. -

Culture Derbyshire Papers

Culture Derbyshire 9 December, 2.30pm at Hardwick Hall (1.30pm for the tour) 1. Apologies for absence 2. Minutes of meeting 25 September 2013 3. Matters arising Follow up on any partner actions re: Creative Places, Dadding About 4. Colliers’ Report on the Visitor Economy in Derbyshire Overview of initial findings D James Followed by Board discussion – how to maximise the benefits 5. New Destination Management Plan for Visit Peak and Derbyshire Powerpoint presentation and Board discussion D James 6. Olympic Legacy Presentation by Derbyshire Sport H Lever Outline of proposals for the Derbyshire ‘Summer of Cycling’ and discussion re: partner opportunities J Battye 7. Measuring Success: overview of performance management Presentation and brief report outlining initial principles JB/ R Jones for reporting performance to the Board and draft list of PIs Date and time of next meeting: Wednesday 26 March 2014, 2pm – 4pm at Creswell Crags, including a tour Possible Bring Forward Items: Grand Tour – project proposal DerbyShire 2015 proposals Summer of Cycling MINUTES of CULTURE DERBYSHIRE BOARD held at County Hall, Matlock on 25 September 2013. PRESENT Councillor Ellie Wilcox (DCC) in the Chair Joe Battye (DCC – Cultural and Community Services), Pauline Beswick (PDNPA), Nigel Caldwell (3D), Denise Edwards (The National Trust), Adam Lathbury (DCC – Conservation and Design), Kate Le Prevost (Arts Derbyshire), Martin Molloy (DCC – Strategic Director Cultural and Community Services), Rachael Rowe (Renishaw Hall), David Senior (National Tramway Museum), Councillor Geoff Stevens (DDDC), Anthony Streeten (English Heritage), Mark Suggitt (Derwent Valley Mills WHS), Councillor Ann Syrett (Bolsover District Council) and Anne Wright (DCC – Arts). Apologies for absence were submitted on behalf of Huw Davis (Derby University), Vanessa Harbar (Heritage Lottery Fund), David James (Visit Peak District), Robert Mayo (Welbeck Estate), David Leat, and Allison Thomas (DCC – Planning and Environment). -

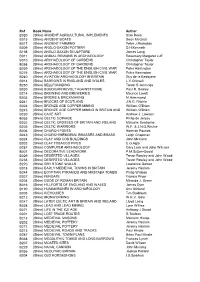

2013 CAG Library Index

Ref Book Name Author B020 (Shire) ANCIENT AGRICULTURAL IMPLEMENTS Sian Rees B015 (Shire) ANCIENT BOATS Sean McGrail B017 (Shire) ANCIENT FARMING Peter J.Reynolds B009 (Shire) ANGLO-SAXON POTTERY D.H.Kenneth B198 (Shire) ANGLO-SAXON SCULPTURE James Lang B011 (Shire) ANIMAL REMAINS IN ARCHAEOLOGY Rosemary Margaret Luff B010 (Shire) ARCHAEOLOGY OF GARDENS Christopher Taylor B268 (Shire) ARCHAEOLOGY OF GARDENS Christopher Taylor B039 (Shire) ARCHAEOLOGY OF THE ENGLISH CIVIL WAR Peter Harrington B276 (Shire) ARCHAEOLOGY OF THE ENGLISH CIVIL WAR Peter Harrington B240 (Shire) AVIATION ARCHAEOLOGY IN BRITAIN Guy de la Bedoyere B014 (Shire) BARROWS IN ENGLAND AND WALES L.V.Grinsell B250 (Shire) BELLFOUNDING Trevor S Jennings B030 (Shire) BOUDICAN REVOLT AGAINST ROME Paul R. Sealey B214 (Shire) BREWING AND BREWERIES Maurice Lovett B003 (Shire) BRICKS & BRICKMAKING M.Hammond B241 (Shire) BROCHS OF SCOTLAND J.N.G. Ritchie B026 (Shire) BRONZE AGE COPPER MINING William O'Brian B245 (Shire) BRONZE AGE COPPER MINING IN BRITAIN AND William O'Brien B230 (Shire) CAVE ART Andrew J. Lawson B035 (Shire) CELTIC COINAGE Philip de Jersey B032 (Shire) CELTIC CROSSES OF BRITAIN AND IRELAND Malcolm Seaborne B205 (Shire) CELTIC WARRIORS W.F. & J.N.G.Ritchie B006 (Shire) CHURCH FONTS Norman Pounds B243 (Shire) CHURCH MEMORIAL BRASSES AND BRASS Leigh Chapman B024 (Shire) CLAY AND COB BUILDINGS John McCann B002 (Shire) CLAY TOBACCO PIPES E.G.Agto B257 (Shire) COMPUTER ARCHAEOLOGY Gary Lock and John Wilcock B007 (Shire) DECORATIVE LEADWORK P.M.Sutton-Goold B029 (Shire) DESERTED VILLAGES Trevor Rowley and John Wood B238 (Shire) DESERTED VILLAGES Trevor Rowley and John Wood B270 (Shire) DRY STONE WALLS Lawrence Garner B018 (Shire) EARLY MEDIEVAL TOWNS IN BRITAIN Jeremy Haslam B244 (Shire) EGYPTIAN PYRAMIDS AND MASTABA TOMBS Philip Watson B027 (Shire) FENGATE Francis Pryor B204 (Shire) GODS OF ROMAN BRITAIN Miranda J. -

Lindow Man: a Bog Body Mystery, Manchester Museum

Subject: Lindow Man: a Bog Body Mystery, Manchester Museum [exhibition review] Author: Stuart Burch, lecturer in museum studies, Nottingham Trent University Source: Museums Journal, vol. 108, no. 7, 2008, pp. 46-49 What objects would you expect to find in an exhibition about Iron Age Britain? Potsherds, swords and other archaeological finds? Human remains? Oh, and don’t forget the obligatory Care Bear and a copy of the Beano. All this and more feature in Manchester Museum’s remarkable exhibition Lindow Man: a Bog Body Mystery. It’s not the first time this star attraction (Lindow Man, not the Care Bear) has returned to the north west since he was discovered in a Cheshire bog in 1984. On each occasion he has been loaned by the British Museum, the institution that was given custody of the body in 1984. Manchester Museum has reawakened this debate through a thought-provoking exhibition and accompanying blog, talks, walks and family activities. While the museum hasn’t suppressed calls for the “restitution” of Lindow Man to the north west, its own position is unequivocal: he will return to London in April 2009. Other things are far less clear. Lindow Man is so well preserved that we even know what he ate before he died. Yet who exactly was he? He died a violent death – but how, when and why? There are many questions and even more answers to this “bog body mystery”. Lindow Man was clearly an important person. And he was as important in life and as he is in death. This is as true today as it was 2,000 years ago. -

Reconstructing Palaeoenvironments of the White Peak Region of Derbyshire, Northern England

THE UNIVERSITY OF HULL Reconstructing Palaeoenvironments of the White Peak Region of Derbyshire, Northern England being a Thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the University of Hull by Simon John Kitcher MPhysGeog May 2014 Declaration I hereby declare that the work presented in this thesis is my own, except where otherwise stated, and that it has not been previously submitted in application for any other degree at any other educational institution in the United Kingdom or overseas. ii Abstract Sub-fossil pollen from Holocene tufa pool sediments is used to investigate middle – late Holocene environmental conditions in the White Peak region of the Derbyshire Peak District in northern England. The overall aim is to use pollen analysis to resolve the relative influence of climate and anthropogenic landscape disturbance on the cessation of tufa production at Lathkill Dale and Monsal Dale in the White Peak region of the Peak District using past vegetation cover as a proxy. Modern White Peak pollen – vegetation relationships are examined to aid semi- quantitative interpretation of sub-fossil pollen assemblages. Moss-polsters and vegetation surveys incorporating novel methodologies are used to produce new Relative Pollen Productivity Estimates (RPPE) for 6 tree taxa, and new association indices for 16 herb taxa. RPPE’s of Alnus, Fraxinus and Pinus were similar to those produced at other European sites; Betula values displaying similarity with other UK sites only. RPPE’s for Fagus and Corylus were significantly lower than at other European sites. Pollen taphonomy in woodland floor mosses in Derbyshire and East Yorkshire is investigated. -

Direct Dating of Neanderthal Remains from the Site of Vindija Cave and Implications for the Middle to Upper Paleolithic Transition

Direct dating of Neanderthal remains from the site of Vindija Cave and implications for the Middle to Upper Paleolithic transition Thibaut Devièsea,1, Ivor Karavanicb,c, Daniel Comeskeya, Cara Kubiaka, Petra Korlevicd, Mateja Hajdinjakd, Siniša Radovice, Noemi Procopiof, Michael Buckleyf, Svante Pääbod, and Tom Highama aOxford Radiocarbon Accelerator Unit, Research Laboratory for Archaeology and the History of Art, University of Oxford, Oxford OX1 3QY, United Kingdom; bDepartment of Archaeology, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of Zagreb, HR-10000 Zagreb, Croatia; cDepartment of Anthropology, University of Wyoming, Laramie, WY 82071; dDepartment of Evolutionary Genetics, Max-Planck-Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, D-04103 Leipzig, Germany; eInstitute for Quaternary Palaeontology and Geology, Croatian Academy of Sciences and Arts, HR-10000 Zagreb, Croatia; and fManchester Institute of Biotechnology, University of Manchester, Manchester M1 7DN, United Kingdom Edited by Richard G. Klein, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, and approved July 28, 2017 (received for review June 5, 2017) Previous dating of the Vi-207 and Vi-208 Neanderthal remains from to directly dating the remains of late Neanderthals and early Vindija Cave (Croatia) led to the suggestion that Neanderthals modern humans, as well as artifacts recovered from the sites they survived there as recently as 28,000–29,000 B.P. Subsequent dating occupied. It has become clear that there have been major pro- yielded older dates, interpreted as ages of at least ∼32,500 B.P. We blems with dating reliability and accuracy across the Paleolithic have redated these same specimens using an approach based on the in general, with studies highlighting issues with underestimation extraction of the amino acid hydroxyproline, using preparative high- of the ages of different dated samples from previously analyzed performance liquid chromatography (Prep-HPLC). -

Group 5: Village Farmlands

GROUP 5: VILLAGE FARMLANds GROUP 5: VILLAGE FARMLANDS P G AGE ROUP 5 S 149-174 Rolling landform and frequent woodland and hedgerow trees are characteristic of the Village Farmlands (© Derbyshire County Council) 149 SECTION 4 150 5A: VILLAGE FARMLANds 5A: VILLAGE FARMLANDS Gently undulating landscape with well treed character (© Derbyshire County Council) KEY CHARACTERISTICS ▪ Gently undulating lowlands, dissected by stream valleys with localised steep slopes and alluvial floodplains; ▪ Moderately fertile loamy and clayey soils with impeded drainage over extensive till deposits on higher ground and gravel terraces bordering main rivers; ▪ Mixed agricultural regime, with localised variations but with a predominance of either dairy farming on permanent pastures, or arable cropping; ▪ Small and moderately sized broadleaved woodlands and copses, often on sloping land; extensive new areas of planting associated with The National Forest; ▪ Hedgerows and frequent oak and ash trees along hedgelines and streams contribute to well treed character of landscape; ▪ Moderately sized well maintained hedged fields across rolling landform create patchwork landscape of contrasting colours and textures; ▪ Extensive ridge and furrow and small historic villages linked by winding lanes contribute to historic and rural character of the landscape; and ▪ Localised influence of large estates. 151 SECTION 4 LANDSCAPE CHARACTER PHYSICAL INFLUENCES The Village Farmlands Landscape Character Type The underlying geology of Permian and Triassic forms part of an extensive tract of landscape that mudstone, siltstone and sandstone gives rise to a extends beyond the Study Area and across wide gently undulating lowland landscape that is further areas of the West Midlands. The landscape is softened by extensive deposits of till and by gravel characterised by undulating farmlands over Triassic terrace deposits and alluvial floodplains fringing the and Permian geology, with localised influences main river channels. -

Guide to the Devonshire Collection Archives

Guide to the Devonshire Collection Archives Part 2 Estate Papers and Related Collections Aidan Haley Assistant Archivist Devonshire Collection 2017 Contents Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 1. Archival Catalogues ...................................................................................................... 2 1.1. Collections originating from estate offices .................................................................. 2 1.2. Other Estate Collections .............................................................................................. 4 1.3. Derbyshire Mining Records ....................................................................................... 10 1.4. Maps and Plans .......................................................................................................... 11 1.5. Related Collections .................................................................................................... 13 2. A note on the accumulation of the Devonshire Estates ................................................ 16 3. A note on the management of the Devonshire Estates ................................................ 18 Summary of the Devonshire Collection Archive Estate Papers and Related Collections Introduction Founded in the 1540s by Sir William Cavendish, and reaching a peak of c.180,000 acres in the late 19th century, for the last four centuries the Devonshire estates have required considerable oversight and administration. -

A∴A∴, Order of the Silver Star, 83, 98 Abelar, T., 437 Aboriginal

INDEX A∴A∴, Order of the Silver Star, 83, 98 Ancient Druid Order, 480 Abelar, T., 437 Ancient Order of Druids, 489 Aboriginal Australians, 407, 602 Andreae, Johann Valentin, 29 Abraham, 488 Anger, Kenneth, 571 Abrahamic, 283, 285, 286, 293, 294, Anglo-Saxon and ‘Prittlewell Prince’, 295, 296, 297, 300, 301, 302, 306, 591, 601. See ‘King of Bling’ 308 Anglo-Saxon and Sutton Hoo, 592. Abram, David, 303 See sacred site Academia Masonica, 85 ‘Anglo-Saxon King of Bling’, 601. Acerbot, 426 See ‘Prittlewell Prince’ Adam Kadmon, 16, 17 Anglo-Saxon, 591, 592, 598 Adler, Margot, 63, 80, 157, 162, Anglo-Saxonism, 579 242– 243, 245, 247– 249, 251, 264, Anglo-Saxons, 484 283, 288 anima/animus, 285 Advaita Vedanta, 91, 95 animal rights, 219 Aesir/aesir, 285, 287, 307n, 415. animism, 301, 302, 306, 393– 411 See Heathenry, deities of ANSE, 585, 586 African-American, 611 Aphrodite, 337, 382 Aïsa, Hadji Soliman ben, 91 Apollo, 284 Albanese, Catherine, 109– 111, 113– 114, Appropriation, 487– 8. See also cultural 434 borrowing; Neo-shamans and Aldred, L., 447, 448 appropriation Alexander Keiller Museum and Druid Aquarian Press, 578 protest, 592, 598, 602, 603 Aquinas, Thomas, 302 Alexandrian Craft, 465, 466, 473 Arn Draiocht Fein (ADF), 489– 90 Alliette, Jean-Baptiste, 25 Aradia, 60 Aloi, Peg, 513, 514, 525, 536, 537 archē, 305 American Nazi Party, 614 Ariosophy/Ariosophist, 619– 20 American Religious Identifi cation Arkana, 578 Survey (Aries), 153, 154, 155, 489. Arthen, Andras Corban, 251 See also City University of New York Aryan, 611– 2, 614– 22 Amerindian, 285, 611 Asatru, 352, 354, 415, 611, 614, 623– 4. -

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-12012-9 — the Cambridge World History of Violence Edited by Garrett G

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-12012-9 — The Cambridge World History of Violence Edited by Garrett G. Fagan , Linda Fibiger , Mark Hudson , Matthew Trundle Index More Information Index Abbink, Jon 608 Aijmer, Göran 608 Abner, and Joab 619–20 Akhenaton, pharaoh 188, 191 ‘abomination’, biblical notion of 615–16 Akhtoy III, pharaoh 345 Abram (Abraham) 611 Akkad, kingdom of 221, 228 sacrifice of son 617 culture 460 Abu-Lughod, Lila 395 fall of 230 Abydos, Egypt, First Dynasty burials 464 Alcibiades 542 acephalous society warfare see hunter- treatment of wife and dog 392–4 gatherers; raiding Alesia, battle of (52 BCE) 154 Achaemenides, son of Amestris 370 Alexander the Great 29, 235, 552 Acts of Ptolemy and Lucius 583, 584 Alexander Severus, emperor 254 Acy-Romance, France, Iron Age human Alexandria, destruction of the Serapeion (391 sacrifice 453 CE) 513, 515, 520–2 Adrianople, battle of (378 CE) 264, 268 Alken Enge, Jutland, Iron Age massacre adultery deposit 448 biblical punishment of women 616 Allan, William 540 punishment by male members of Allen, Danielle 383 household 385 Alvarado, Pedro de 214 by women in Greece 384, 390 Amarna Letters, between Babylon and Aegospotami, battle of (405 BCE) 538 Egypt 234 Aeneas 550 Amenemhet II, pharaoh 346 and Anchises 676, 681 Amenhotep II, pharaoh 183, 186 Africa Americas Homo erectus 58 evidence of violence in Paleoamericans Homo sapiens in 58 23, 54 Later Stone Age 99–104, 104 initial colonisation 199 see also hunter-gatherers; Kalahari ritualised violence 7 Agathonike, martyr 583 skeletal evidence