The Archaeology Coursebook: an Introduction to Study Skills

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Book Self-Publishing Best Practices

Montana Tech Library Digital Commons @ Montana Tech Graduate Theses & Non-Theses Student Scholarship Fall 2019 Book Self-Publishing Best Practices Erica Jansma Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.mtech.edu/grad_rsch Part of the Communication Commons Book Self-Publishing Best Practices by Erica Jansma A project submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of M.S. Technical Communication Montana Tech 2019 ii Abstract I have taken a manuscript through the book publishing process to produce a camera-ready print book and e-book. This includes copyediting, designing layout templates, laying out the document in InDesign, and producing an index. My research is focused on the best practices and standards for publishing. Lessons learned from my research and experience include layout best practices, particularly linespacing and alignment guidelines, as well as the limitations and capabilities of InDesign, particularly its endnote functionality. Based on the results of this project, I can recommend self-publishers to understand the software and distribution platforms prior to publishing a book to ensure the required specifications are met to avoid complications later in the process. This document provides details on many of the software, distribution, and design options available for self-publishers to consider. Keywords: self-publishing, publishing, books, ebooks, book design, layout iii Dedication I dedicate this project to both of my grandmothers. I grew up watching you work hard, sacrifice, trust, and love with everything you have; it was beautiful; you are beautiful; and I hope I can model your example with a fraction of your grace and fruitfulness. Thank you for loving me so well. -

New Traveling Exhibition from the Guild of Book Workers with 50 New Book Artists' Work Form Across the Country

New Traveling Exhibition from the Guild of Book Workers with 50 New Book Artists’ Work form Across the Country May 24, 2021 Contact Person: Jeanne Goodman Contact Email: [email protected] The Guild of Book Workers traveling exhibition will travel from June 2021 to September 2022. The opening and close dates for “Wild/LIFE” should be confirmed with each venue before travel and to check local public health precautions in place due to COVID-19. EXHIBITION “Wild/LIFE: Guild of Book Workers Triannual Exhibition”, June 2021 to September 2022 DESCRIPTION This exhibition features approximately 50 works by members of the Guild of Book Workers, an book artists organization that promotes interest in and awareness of the tradition of the book and paper arts by maintaining high standards of workmanship, hosting educational opportunities, and sponsoring exhibits. Members were invited to interpret the theme of “wildlife” in any way they wish, be it literal or abstract, humorous or serious. In a biological sense, wildlife describes the myriad of creatures sharing this planet, interacting and adapting, all connected to each other and their environment. "Wild" also describes an untamable essence that survives despite the constraints of society and culture. As craftspeople, knowledge of materials and keen observation of how they behave (and often how they refuse to comply) is an integral part of the practice of book making, and a reminder of how traditional bookbinding materials originate in nature. The exhibition opens at the American Bookbinders Museum in San Francisco, CA in June 2021, and will continue to travel to five additional venues across the country, closing in the fall of 2022. -

Human Remains, Museum Space and the 'Poetics of Exhibiting'

23 — VOLUME 10 2018 UNIVERSITY MUSEUMS AND COLLECTIONS JOURNAL Human remains, museum space and the ‘poetics of exhibiting’ Kali Tzortzi Abstract The paper explores the role of the design of museum space in the chal- lenges set by the display of human remains. Against the background of ‘embodied understanding’, ‘multisensory learning’ and ‘affective distance’ and of contextual case studies, it analyses the innovative spa- tial approach of the Moesgaard Museum of the University of Aarhus, which, it argues, humanizes bog bodies and renders them an integra- tive part of an experiential, embodied and sensory narrative. This allows the mapping of spatial shifts and new forms of engagement with human remains, and also demonstrates the role of university museums as spaces for innovation and experimentation. 24 — VOLUME 10 2018 UNIVERSITY MUSEUMS AND COLLECTIONS JOURNAL Introduction and research question This paper aims to explore the issue of the respectful presentation of human physical remains in contextual exhibitions by looking at the role of museum space in the challenges set by their display, with particular reference to the contribution of experimentation in the university museum environ- ment. The debate raised by the understanding that human remains “are not just another artefact” (stated by CASSMAN et al. 2007, in GIESEN 2013, 1) is extensively discussed in the literature, and increasingly explored through a range of museum practices. In terms of theoretical understanding, authors have sought to acquire an overall picture of approaches towards the care of human remains so as to better understand the challenges raised. For example, among the most recent publica- tions, O’Donnabhain and Lozada (2014) examine the global diversity of attitudes to archaeological human remains and the variety of approaches to their study and curation in different countries. -

Fall 2003 Online Supplement

Electronic Archaeology News Volume 21 Number 3, Online Supplement Fall 2003 From the Editor: MVAC is excited to offer a new way for our members to receive current news about ongoing projects, new finds and upcoming events. We will continue to mail out a newsletter with announcements three times a year, and will provide more information in the online supplement. Please let me know what you think of this change and any suggestions you have for new MVAC at the University material to include. Members who would like a hard copy of the supplement of Wisconsin - La Crosse mailed to their homes can contact me at (608) 785-8454 or 1725 State Street [email protected]. Enjoy the newsletter! La Crosse, WI 54601 Jean Dowiasch, Editor www.uwlax.edu/mvac ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ State Highway 33 Projects Yields Upland Sites Vicki Twinde, Research Archaeologist In June of 2003, MVAC personnel conducted a MVAC has recommended more Phase I survey of approximately 7 miles of STH 33, archaeological work be done on from the intersection of County Highway F and STH these sites. Therefore, this fall, 33 at the top of Irish Hill to approximately 1/2 mile pending landowner permis- east of the town of St. Joseph. This is part of a sions, MVAC will undertake Wisconsin Department of Transportation project in additional archaeological work which approximately 21 miles of STH 33 will be re- on eight of these sites. done from CTH F all the way into the town of Cashton. The highway project will be completed in three different sections, as will the archaeology. -

Archaeology Book Collection 2013

Archaeology Book Collection 2013 The archaeology book collection is held on the upper floor of the Student Research Room (2M.25) and is arranged in alphabetical order. The journals in this collection are at the end of the document identified with the ‘author’ as ‘ZJ’. Use computer keys CTRL + F to search for a title/author. Abulafia, D. (2003). The Mediterranean in history. London, Thames & Hudson. Adkins, L. and R. Adkins (1989). Archaeological illustration. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press. Adkins, L. and R. A. Adkins (1982). A thesaurus of British archaeology. Newton Abbot, David & Charles. Adkins, R., et al. (2008). The handbook of British archaeology. London, Constable. Alcock, L. (1963). Celtic Archaeology and Art, University of Wales Press. Alcock, L. (1971). Arthur's Britain : history and archaeology, AD 367-634. London, Allen Lane. Alcock, L. (1973). Arthur's Britain: History and Archaeology AD 367-634. Harmondsworth, Penguin. Aldred, C. (1972). Akhenaten: Pharaoh of Egypt. London, Abacus; Sphere Books. Alimen, H. and A. H. Brodrick (1957). The prehistory of Africa. London, Hutchinson. Allan, J. P. (1984). Medieval and Post-Medieval Finds from Exeter 1971-1980. Exeter, Exeter City Council and the University of Exeter. Allen, D. F. (1980). The Coins of the Ancient Celts. Edinburgh, Edinburgh University Press. Allibone, T. E. and S. Royal (1970). The impact of the natural sciences on archaeology. A joint symposium of the Royal Society and the British Academy. Organized by a committee under the chairmanship of T. E. Allibone, F.R.S, London: published for the British Academy by Oxford University Press. Alves, F. and E. -

Dynamics of Religious Ritual: Migration and Adaptation in Early Medieval Britain

Dynamics of Religious Ritual: Migration and Adaptation in Early Medieval Britain A Dissertation SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Brooke Elizabeth Creager IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Peter S. Wells August 2019 Brooke Elizabeth Creager 2019 © For my Mom, I could never have done this without you. And for my Grandfather, thank you for showing me the world and never letting me doubt I can do anything. Thank you. i Abstract: How do migrations impact religious practice? In early Anglo-Saxon England, the practice of post-Roman Christianity adapted after the Anglo-Saxon migration. The contemporary texts all agree that Christianity continued to be practiced into the fifth and sixth centuries but the archaeological record reflects a predominantly Anglo-Saxon culture. My research compiles the evidence for post-Roman Christian practice on the east coast of England from cemeteries and Roman churches to determine the extent of religious change after the migration. Using the case study of post-Roman religion, the themes religion, migration, and the role of the individual are used to determine how a minority religion is practiced during periods of change within a new culturally dominant society. ii Table of Contents Abstract …………………………………………………………………………………...ii List of Figures ……………………………………………………………………………iv Preface …………………………………………………………………………………….1 I. Religion 1. Archaeological Theory of Religion ...………………………………………………...3 II. Migration 2. Migration Theory and the Anglo-Saxon Migration ...……………………………….42 3. Continental Ritual Practice before the Migration, 100 BC – AD 400 ………………91 III. Southeastern England, before, during and after the Migration 4. Contemporary Accounts of Religion in the Fifth and Sixth Centuries……………..116 5. -

Guidelines for the Field Collection of Archaeological Materials and Standard Operating Procedures for Curating Department of Defense Archaeological Collections

Guidelines for the Field Collection of Archaeological Materials and Standard Operating Procedures for Curating Department of Defense Archaeological Collections Prepared for the Legacy Resource Management Program Office Legacy Project No. 98-1714 Mandatory Center of Expertise for the Curation and Management of Archaeological Collections Form Approved REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE OMB No. 0704-0188 Public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instructions, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing this burden, to Washington Headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports, 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302, and to the Office of Management and Budget, Paperwork Reduction Project (0704-0188), Washington, DC 20503. 1. AGENCY USE ONLY (Leave blank) 2. REPORT DATE 1999 3. REPORT TYPE AND DATES COVERED 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE 5. FUNDING NUMBERS Guidelines for the Field Collection of Archaeological Materials and Standard Operating Procedures for Curation Department of Defense Archaeological Collections 6. AUTHORS Suzanne Griset and Marc Kodack 7. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) PERFORMING ORGANIZATION REPORT NUMBER U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, St. Louis District 1222 Spruce Street (CEMVS-ED-Z) St. Louis, Missouri 63103-2833 9. SPONSORING/MONITORING AGENCY NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 10. SPONSORING/MONITORING AGENCY Legacy Resource Management Program Office REPORT NUMBER Office of Deputy Under Secretary of Defense (Environmental Security) Legacy Project No. -

![Review (Abridged) of Bogle, Sophia S.W. Book Restoration Unveiled: an Essential Guide for Bibliophiles. [N.P.]: First Editions Press, 2019](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0483/review-abridged-of-bogle-sophia-s-w-book-restoration-unveiled-an-essential-guide-for-bibliophiles-n-p-first-editions-press-2019-220483.webp)

Review (Abridged) of Bogle, Sophia S.W. Book Restoration Unveiled: an Essential Guide for Bibliophiles. [N.P.]: First Editions Press, 2019

Syracuse University From the SelectedWorks of Peter D Verheyen June, 2019 Review (Abridged) of Bogle, Sophia S.W. Book Restoration Unveiled: An Essential Guide for Bibliophiles. [n.p.]: First Editions Press, 2019. Peter D Verheyen This work is licensed under a Creative Commons CC_BY-NC-SA International License. Available at: https://works.bepress.com/peter_verheyen/54/ BOOK REVIEW by Peter D. Verheyen Book Restoration Unveiled - An Essential Guide for Bibliophiles <' ~ Sophia S. w Bogle I.... -::-,·::.. :-;:v->~~-.•;,-/..-ic·-<-.· -.. ,<:-/s-'.'7-.-·::-.)-_;.;~-':-"li-/}-~.\..... ~\-,,:~-;t-,\t-\'.?,.....,~~~j--.;t'.--;.;·-j~-}l: .....}-l-f.J ~ u 0 (Ashland, OR: First Editions Press, 2019) :::0 (D o' 5: In Book Restoration Unveiled, Sophia S.W Bogle Book Restoration (D r6 sets out "to provide the tools to spot restorations so ~ that everyone can make more informed decisions s'-I when buying or selling books." The second reason was CJ UnvedJ c% p.J her realization that "instead of a simple list of clear "D 8 0 0 terminology, [there] was a distressing lack of agreement ~ ~ (") (D and even confusion about the most basic of book repair 0 () 8 ~ If ......__ (D terms." She writes, "this book [is] a bridge between the Iv :::0 /,8'~.4' 0 ....... world of collecting, buying, and selling books, and that <..O-< (D ......__ '-I of book repair, restoration, and conservation." In the ~ 0 (D case of the latter, she describes some of the minutiae ::: ~- 8" ~ 0 (") of the book such as structure, and treatments, good ;;,;- p.J ~ :::0 as well as bad. But, "this is not a 'how-to' manual." (D u ~ (D Rather, it is a "guide to help you understand the world S; o' of restoration, to recognize restorations, and to choose §. -

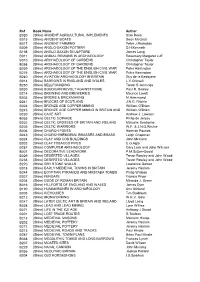

2013 CAG Library Index

Ref Book Name Author B020 (Shire) ANCIENT AGRICULTURAL IMPLEMENTS Sian Rees B015 (Shire) ANCIENT BOATS Sean McGrail B017 (Shire) ANCIENT FARMING Peter J.Reynolds B009 (Shire) ANGLO-SAXON POTTERY D.H.Kenneth B198 (Shire) ANGLO-SAXON SCULPTURE James Lang B011 (Shire) ANIMAL REMAINS IN ARCHAEOLOGY Rosemary Margaret Luff B010 (Shire) ARCHAEOLOGY OF GARDENS Christopher Taylor B268 (Shire) ARCHAEOLOGY OF GARDENS Christopher Taylor B039 (Shire) ARCHAEOLOGY OF THE ENGLISH CIVIL WAR Peter Harrington B276 (Shire) ARCHAEOLOGY OF THE ENGLISH CIVIL WAR Peter Harrington B240 (Shire) AVIATION ARCHAEOLOGY IN BRITAIN Guy de la Bedoyere B014 (Shire) BARROWS IN ENGLAND AND WALES L.V.Grinsell B250 (Shire) BELLFOUNDING Trevor S Jennings B030 (Shire) BOUDICAN REVOLT AGAINST ROME Paul R. Sealey B214 (Shire) BREWING AND BREWERIES Maurice Lovett B003 (Shire) BRICKS & BRICKMAKING M.Hammond B241 (Shire) BROCHS OF SCOTLAND J.N.G. Ritchie B026 (Shire) BRONZE AGE COPPER MINING William O'Brian B245 (Shire) BRONZE AGE COPPER MINING IN BRITAIN AND William O'Brien B230 (Shire) CAVE ART Andrew J. Lawson B035 (Shire) CELTIC COINAGE Philip de Jersey B032 (Shire) CELTIC CROSSES OF BRITAIN AND IRELAND Malcolm Seaborne B205 (Shire) CELTIC WARRIORS W.F. & J.N.G.Ritchie B006 (Shire) CHURCH FONTS Norman Pounds B243 (Shire) CHURCH MEMORIAL BRASSES AND BRASS Leigh Chapman B024 (Shire) CLAY AND COB BUILDINGS John McCann B002 (Shire) CLAY TOBACCO PIPES E.G.Agto B257 (Shire) COMPUTER ARCHAEOLOGY Gary Lock and John Wilcock B007 (Shire) DECORATIVE LEADWORK P.M.Sutton-Goold B029 (Shire) DESERTED VILLAGES Trevor Rowley and John Wood B238 (Shire) DESERTED VILLAGES Trevor Rowley and John Wood B270 (Shire) DRY STONE WALLS Lawrence Garner B018 (Shire) EARLY MEDIEVAL TOWNS IN BRITAIN Jeremy Haslam B244 (Shire) EGYPTIAN PYRAMIDS AND MASTABA TOMBS Philip Watson B027 (Shire) FENGATE Francis Pryor B204 (Shire) GODS OF ROMAN BRITAIN Miranda J. -

Bioarchaeology (Anthropological Archaeology) - Mario ŠLAUS

PHYSICAL (BIOLOGICAL) ANTHROPOLOGY - Bioarchaeology (Anthropological Archaeology) - Mario ŠLAUS BIOARCHAEOLOGY (ANTHROPOLOGICAL ARCHAEOLOGY) Mario ŠLAUS Department of Archaeology, Croatian Academy of Sciences and Arts, Zagreb, Croatia. Keywords: Bioarchaeology, archaeological, forensic, antemortem, post-mortem, perimortem, traumas, Cribra orbitalia, Harris lines, Tuberculosis, Leprosy, Treponematosis, Trauma analysis, Accidental trauma, Intentional trauma, Osteological, Degenerative disease, Habitual activities, Osteoarthritis, Schmorl’s nodes, Tooth wear Contents 1. Introduction 1.1. Definition of Bioarchaeology 1.2. History of Bioarchaeology 2. Analysis of Skeletal Remains 2.1. Excavation and Recovery 2.2. Human / Non-Human Remains 2.3. Archaeological / Forensic Remains 2.4. Differentiating between Antemortem/Postmortem/Perimortem Traumas 2.5. Determination of Sex 2.6. Determination of Age at Death 2.6.1. Age Determination in Subadults 2.6.2. Age Determination in Adults. 3. Skeletal and dental markers of stress 3.1. Linear Enamel Hypoplasia 3.2. Cribra Orbitalia 3.3. Harris Lines 4. Analyses of dental remains 4.1. Caries 4.2. Alveolar Bone Disease and Antemortem Tooth Loss 5. Infectious disease 5.1. Non–specific Infectious Diseases 5.2. Specific Infectious Disease 5.2.1. Tuberculosis 5.2.2. Leprosy 5.2.3. TreponematosisUNESCO – EOLSS 6. Trauma analysis 6.1. Accidental SAMPLETrauma CHAPTERS 6.2. Intentional Trauma 7. Osteological and dental evidence of degenerative disease and habitual activities 7.1. Osteoarthritis 7.2. Schmorl’s Nodes 7.3. Tooth Wear Caused by Habitual Activities 8. Conclusion Glossary Bibliography Biographical Sketch ©Encyclopedia of Life Support Systems (EOLSS) PHYSICAL (BIOLOGICAL) ANTHROPOLOGY - Bioarchaeology (Anthropological Archaeology) - Mario ŠLAUS 1. Introduction 1.1. Definition of Bioarchaeology Bioarchaeology is the study of human biological remains within their cultural (archaeological) context. -

Monuments, Materiality, and Meaning in the Classical Archaeology of Anatolia

MONUMENTS, MATERIALITY, AND MEANING IN THE CLASSICAL ARCHAEOLOGY OF ANATOLIA by Daniel David Shoup A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Classical Art and Archaeology) in The University of Michigan 2008 Doctoral Committee: Professor Elaine K. Gazda, Co-Chair Professor John F. Cherry, Co-Chair, Brown University Professor Fatma Müge Göçek Professor Christopher John Ratté Professor Norman Yoffee Acknowledgments Athena may have sprung from Zeus’ brow alone, but dissertations never have a solitary birth: especially this one, which is largely made up of the voices of others. I have been fortunate to have the support of many friends, colleagues, and mentors, whose ideas and suggestions have fundamentally shaped this work. I would also like to thank the dozens of people who agreed to be interviewed, whose ideas and voices animate this text and the sites where they work. I offer this dissertation in hope that it contributes, in some small way, to a bright future for archaeology in Turkey. My committee members have been unstinting in their support of what has proved to be an unconventional project. John Cherry’s able teaching and broad perspective on archaeology formed the matrix in which the ideas for this dissertation grew; Elaine Gazda’s support, guidance, and advocacy of the project was indispensible to its completion. Norman Yoffee provided ideas and support from the first draft of a very different prospectus – including very necessary encouragement to go out on a limb. Chris Ratté has been a generous host at the site of Aphrodisias and helpful commentator during the writing process. -

Lindow Man: a Bog Body Mystery, Manchester Museum

Subject: Lindow Man: a Bog Body Mystery, Manchester Museum [exhibition review] Author: Stuart Burch, lecturer in museum studies, Nottingham Trent University Source: Museums Journal, vol. 108, no. 7, 2008, pp. 46-49 What objects would you expect to find in an exhibition about Iron Age Britain? Potsherds, swords and other archaeological finds? Human remains? Oh, and don’t forget the obligatory Care Bear and a copy of the Beano. All this and more feature in Manchester Museum’s remarkable exhibition Lindow Man: a Bog Body Mystery. It’s not the first time this star attraction (Lindow Man, not the Care Bear) has returned to the north west since he was discovered in a Cheshire bog in 1984. On each occasion he has been loaned by the British Museum, the institution that was given custody of the body in 1984. Manchester Museum has reawakened this debate through a thought-provoking exhibition and accompanying blog, talks, walks and family activities. While the museum hasn’t suppressed calls for the “restitution” of Lindow Man to the north west, its own position is unequivocal: he will return to London in April 2009. Other things are far less clear. Lindow Man is so well preserved that we even know what he ate before he died. Yet who exactly was he? He died a violent death – but how, when and why? There are many questions and even more answers to this “bog body mystery”. Lindow Man was clearly an important person. And he was as important in life and as he is in death. This is as true today as it was 2,000 years ago.