Transatlantic: the Flying Boats of Foynes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Extended Travel OPEN to STUDENTS 18 and OLDER

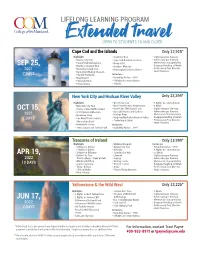

LIFELONG LEARNING PROGRAM Extended travel OPEN TO STUDENTS 18 AND OLDER Cape Cod and the Islands Only $2,925* Highlights • Cranberry Bog • Sightseeing per Itinerary • Boston City Tour • Cape Cod National Seashore • Admissions per Itinerary • Faneuil Hall Marketplace • Newport RI • Motorcoach Transportation SEP 25, • Martha’s Vineyard Tour • Breakers Mansion • Baggage Handling at Hotels • Professional Tour Director 2021 • Nantucket Island Visit • New England Lobster Dinner • Nantucket Whaling Museum • Hotel Transfers 7 DAYS • Plimoth Plantation Inclusions • Mayflower II • Roundtrip Airfare – HOU • Plymouth Rock • 6 Nights Accommodations • Provincetown • 9 Meals .................................................................................................................................................... New York City and Hudson River Valley Only $3,399* Highlights • West Point Tour • 6 Nights Accommodations • New York City Tour • New Paltz/Historic Huguenot St. • 8 Meals OCT 15, • Statue of Liberty/Ellis Island • Hyde Park-FDR Historic Site • Sightseeing per Itinerary • 9/11 Memorial/Museum • Boscobel House and Gardens • Admissions per Itinerary 2021 • Broadway Show • Hudson River • Motorcoach Transportation • One World Trade Center/ • Kingston/Manhattan/Hudson Valley • Baggage Handling at Hotels 7 DAYS • Professional Tour Director Observation Deck • Crown Maple Syrup • Hotel Transfers • Rockefeller Center Inclusions • Times Square and Central Park • Roundtrip Airfare – HOU ................................................................................................................................................... -

Limerick Timetables

Limerick B A For more information For online information please visit: locallinklimerick.ie Call us at: 069 78040 Email us at: [email protected] Ask your driver or other staff member for assistance Operated By: Local Link Limerick Fares: Adult Return/Single: €5.00/€3.00 Student & Child Return/Single: €3.00/€2.00 Adult Train Connector: €1.50 Student/Child Train Connector: €1.00 Multi Trip Adult/Child: €8.00/€5.00 Weekly Student/Child: €12.00 5 day Weekly Adult: €20.00 6 day Weekly Adult: €25.00 Free Travel Pass holders and children under 5 years travel free Our vehicles are wheelchair accessible Contents Route Page Ballyorgan – Ardpatrick – Kilmallock – Charleville – Doneraile 4 Newcastle West Service (via Glin & Shanagolden) 12 Charleville Child & Family Education Centre 20 Spa Road Kilfinane to Mitchelstown 21 Mountcollins to Newcastle West (via Dromtrasna) 23 Athea Shanagolden to Newcastle West Desmond complex 24 Castlemahon via Ballingarry to Newcastle West - Desmond Complex 25 Castlmahon to Newcastle West - Desmond Complex 26 Ballykenny to Newcastle West- Desmond Complex 27 Shanagolden to Newcastle West - Special Olympics 28 Tournafulla to Newcastle West - Special Olympics 29 Abbeyfeale to Newcastle West - Special Olympics 30 Elton to Hospital 31 Adare to Newcastle West 32 Kilfinny via Adare to Newcastle West 33 Feenagh via Ballingarry to Newcastle West - Desmond Complex 34 Knockane via Patrickswell to Dooradoyle 35 Knocklong to Dooradoyle 36 Rathkeale via Askeaton to Newcastle West to Desmond Complex 37 Ballingarry to -

Limerick Walking Trails

11. BALLYHOURA WAY 13. Darragh Hills & B F The Ballyhoura Way, which is a 90km way-marked trail, is part of the O’Sullivan Beara Trail. The Way stretches from C John’s Bridge in north Cork to Limerick Junction in County Tipperary, and is essentially a fairly short, easy, low-level Castlegale LOOP route. It’s a varied route which takes you through pastureland of the Golden Vale, along forest trails, driving paths Trailhead: Ballinaboola Woods Situated in the southwest region of Ireland, on the borders of counties Tipperary, Limerick and Cork, Ballyhoura and river bank, across the wooded Ballyhoura Mountains and through the Glen of Aherlow. Country is an area of undulating green pastures, woodlands, hills and mountains. The Darragh Hills, situated to the A Car Park, Ardpatrick, County southeast of Kilfinnane, offer pleasant walking through mixed broadleaf and conifer woodland with some heathland. Directions to trailhead Limerick C The Ballyhoura Way is best accessed at one of seven key trailheads, which provide information map boards and There are wonderful views of the rolling hills of the surrounding countryside with Galtymore in the distance. car parking. These are located reasonably close to other services and facilities, such as shops, accommodation, Services: Ardpatrick (4Km) D Directions to trailhead E restaurants and public transport. The trailheads are located as follows: Dist/Time: Knockduv Loop 5km/ From Kilmallock take the R512, follow past Ballingaddy Church and take the first turn to the left to the R517. Follow Trailhead 1 – John’s Bridge Ballinaboola 10km the R517 south to Kilfinnane. At the Cross Roads in Kilfinnane, turn right and continue on the R517. -

1911 Census, Co. Limerick Householder Index Surname Forename Townland Civil Parish Corresponding RC Parish

W - 1911 Census, Co. Limerick householder index Surname Forename Townland Civil Parish Corresponding RC Parish Wade Henry Turagh Tuogh Cappamore Wade John Cahernarry (Cripps) Cahernarry Donaghmore Wade Joseph Drombanny Cahernarry Donaghmore Wakely Ellen Creagh Street, Glin Kilfergus Glin Walker Arthur Rooskagh East Ardagh Ardagh Walker Catherine Blossomhill, Pt. of Rathkeale Rathkeale (Rural) Walker George Rooskagh East Ardagh Ardagh Walker Henry Askeaton Askeaton Askeaton Walker Mary Bishop Street, Newcastle Newcastle Newcastle West Walker Thomas Church Street, Newcastle Newcastle Newcastle West Walker William Adare Adare Adare Walker William F. Blackabbey Adare Adare Wall Daniel Clashganniff Kilmoylan Shanagolden Wall David Cloon and Commons Stradbally Castleconnell Wall Edmond Ballygubba South Tankardstown Kilmallock Wall Edward Aughinish East Robertstown Shanagolden Wall Edward Ballingarry Ballingarry Ballingarry Wall Ellen Aughinish East Robertstown Shanagolden Wall Ellen Ballynacourty Iveruss Askeaton Wall James Abbeyfeale Town Abbeyfeale Abbeyfeale Wall James Ballycullane St. Peter & Paul's Kilmallock Wall James Bruff Town Bruff Bruff Wall James Mundellihy Dromcolliher Drumcolliher, Broadford Wall Johanna Callohow Cloncrew Drumcollogher Wall John Aughalin Clonelty Knockderry Wall John Ballycormick Shanagolden Shanagolden & Foynes Wall John Ballygubba North Tankardstown Kilmallock Wall John Clashganniff Shanagolden Shanagolden & Foynes Wall John Ranahan Rathkeale Rathkeale Wall John Shanagolden Town Shanagolden Shanagolden & Foynes -

ORIGINAL BUREAUOFMILITARYHISTORY1913-21 BUROSTAIREMILEATA1913-21 No. W.S. 1,272 ROINN COSANTA. BUREAU of MILITARY HISTORY, 1913

BUREAUOFMILITARYHISTORY1913-21 BUROSTAIREMILEATA1913-21 No. W.S. 1,272 ORIGINAL ROINN COSANTA. BUREAU OF MILITARY HISTORY, 1913-21. STATEMENT BY WITNESS. DOCUMENT NO. W.S. 1272 Witness James Collins, T.D., Convent Terrace, Abbeyfeale, Co. Limerick. Identity. Captain Abbeyfeale Company; Vice O/C. Abbeyfeale Battalion; Brigade Adjutant West Limerick Brigade. Subject. Abbeyfeale Irish Company Volunteers, Co. Limerick, l9l5-192l. Conditions, if any, Stipulated by Witness. Nil File No. S.2564 Form B.S.M.2 1913-21 BUREAUOFMILITARYHISTORY BUROSTAIREMILEATA1913-21 No. W.S. 1,272 STATEMENT OF JAMES COLLINS, T.D., ORIGINAL Convent Terrace, Abbeyfeale, Co. Limerick. I was born in the parish of Abbeyfeale on the 31st October, 1900, and was one of a family of three boys and three girls. My parents, who were farmers, sent me to the local national school until I was fourteen years of age, after which I attended a private school run by a man named Mr. Danaher. While attending the private school, I became an apprentice to a chemist in the town of Abbeyfeale whose name was Richard B. Woulfe. After completing my apprenticeship, I was retained in his employment for some years until I was forced to go on the run during the Black and Tan terror. Mr. Woulfe's wife was Miss Cathie Colbert, sister of Con Colbert (executed after Easter Week 1916) and James Colbert, and cousin of Michael Colbert who later became Brigade Vice 0/C, West Limerick Brigade. The Woulfe's were great supporters of the Irish independence movement and their shop and house, from the earliest days of the movement, became a meeting place for men like Con Colbert, Captain Ned Daly and others who later figured perminently in the fight for freedom. -

PAN Ilher/CAN WORLD A/Rwat Y' ~ S;S/~M Of1j,{'(--7Fr1ilf Czjjt'rs

~ PAA PAA PAN AMERJCAN WOHLD AIRWAYS IN IRELAND HISTORY HE f,rst il\spirin~ c1Llph'r in .til c history of "vi<ttion in Ircland will T always h,· 11flk"L1 closcly WI' h the name o[ PUll Anlerlcan \Vorld Airways. U n Ihe afternoon oi July (;th, 19.17, while cmwds lin(:J the mads leading to the Co. Limerick village of F ('ynes ann ncw,pal"'rmr:-n lllSTOHY representing the press of th" Wo rld were there to retell the story, the giant Pan Anwrican Airways Sikor',ky Clippcr III hlawn in acco;s the Atlantic ,~nd landed the quiet waters of th,. Shannon amid gn-"t. ORGANJZATION II" chN:r!; fmrn til(' crowds. This was ;hc f,rst cornm"ccial aircraft ever 10 arrive in lrchnn from the l lnil<'oi St.ates ,)f .'\mericCl. Not onl" was th:, PEIISONNEL achi"vern('llt of this Clipper hif: news ill lr('\a nd, hnt it ranI( ';). nl1le pf prid" in the h eart o f e\'ITV Trish n"me in the United States. The crllwd haJ every rcason to cheCI. fnr Captain lIarold Cra),. Pilot of thc Clippcl. han lJriclg..d the Atlantic in what was then thc remarkable tillle of 11 hou r" ane! 40 Illinutcs. 'filat was" memorablc <lay at Foynt';. fnr only the previous cvcning the Imperial Airways Flying Boat' 'Caledonia" look ,) fl on the lirst westbound lIight to BotwO()[I. N"wfoundlantl, tyill/-: th(: kllot in mid-Atlantic wh~n C;ll'lain \Vilcockson and Captaill Cray of ihp. (lip!'('r gr,' c\cd tach other by radio Io'\P.l'hone ut a I\t'ight of ;limost 'J .ooo fCd. -

Information and Services for Older People Across Limerick

INFORMATION AND SERVICES FOR OLDER PEOPLE ACROSS LIMERICK 1 INFORMATION AND SERVICES FOR OLDER PEOPLE ACROSS LIMERICK CONTENTS USEFUL NUMBERS .............................................................................3 SECTION 1: BEING POSITIVE: ACTIVITIES INVOLVING OLDER PEOPLE Active Retired Group .............................................................................4 PROBUS ..............................................................................................5 Courses and Activities ........................................................................5 General Course Providers ....................................................................5 Computer Skills Courses .....................................................................6 Men’s Sheds .......................................................................................7 Women’s Groups ............................................................................... 9 Get Togethers and Craft Groups .......................................................10 Cards .................................................................................................10 Bingo .................................................................................................11 Music and Dancing ............................................................................12 Day Centres ......................................................................................13 Libraries ............................................................................................18 -

Mount Trenchard in Co. Limerick

Mount Trenchard in Co. SLIGO Limerick OFFALY Mount Trenchard accommodation centre is located just outside Foynes. Limerick County is located in the West of Ireland. This centre houses single males. COUNTY LIMERICK Centre Managers: Raja Anjum & Andrius Gronskis Community Welfare Officer: Gerry Meehan Jesuit Refugee Service Ireland LOCAL SERVICES PUBLIC SERVICES Social Welfare Citizen’s Information Service Intreo Centre, Dominick Street, Limerick Riverstone House, Ground floor, Henry Street, Phone: 061212200 Limerick, V94 3T28 Phone: 0761075780 Foynes Garda Station Ballynacragga North, Foynes, Co. Limerick Phone: 06965122 VOLUNTEERING AND EDUCATION Limerick Volunteer Centre Limerick and Clare Education and 40, The Tait Business Centre, Training Board Dominic St, Limerick Marshal House, Dooradoyle Rd, Phone: 0877387481 Limerick, V94 HAC4 Phone: 061442100 Limerick City Library The Granary, Michael St, Limerick Foynes Library Phone: 061407510 Main St, Ballynacragga North, Foynes, Co. Limerick Phone: 06965365 SUPPORT GROUPS Jesuit Refugee Service Doras Luimní: Legal Aid Della Strada, Dooradoyle, Limerick 51 O’Connell St, Limerick Phone: 061480922 Phone: 061310328 Email: [email protected] GOSHH: LGBT Support Legal Queries: [email protected] Redwood Place, 18 Davis Street, Limerick, V94 K377 Women’s Organisation Phone: 061314354 Northside Family Resource Centre Clonconnane Road, Ballynanty, Co. Limerick Confidential Helpline: 061316661 Phone: 061326623 National LGBT Support Line 1890 929 539 CHILD AND FAMILY Northside Family Resource Centre Southill Family Resource Centre Clonconnane Road, Ballynanty, Co. Limerick 268 Avondale Court, Co. Limerick Phone: 061326623 Phone: 061440250 For information on schools in the area visit: www.education.ie/en/find-a-school SPORTS CLUBS Old Christians GAA Club Ballynanty Rovers FC Rathbane, Co. Limerick 91 Inis Mor, Fr. -

Revised Foynes

Ireland, the Irish Meteorological Service and "The Emergency" [an expanded version of a paper that appeared in Weather 56(11) (2001) 387 - 397] Donard de Cogan1and John A. Kington2 1School of Information Systems 2Climatic Research Unit University of East Anglia, Norwich NR4 7TJ Note: The figures that appeared in the original article are cited next to the figures in this revised version Introduction Obtaining meteorological information about the development and movement of weather systems over the North Atlantic was an essential element of forecasting for both Allied and Axis forces during the war. An obvious source for such data was Ireland, or Eire as it was then called. Yet, Ireland had declared itself as neutral and in an effort to ignore the events beyond its borders, the euphemism, "The Emergency", was generally adopted. However, the official line on neutrality seems to have been slightly different from what actually happened. For example, an examination of the synoptic coverage on the wartime weather maps presented by Lewis (1985) shows that meteorological observations were available at the Central Forecasting Office, Dunstable from southern as well as Northern Ieland (Fig. 1). The key factor in this, something which is frequently overlooked, is the detail contained in the Anglo-Irish Treaty of 1922 which led to the establishment of the Irish Free State. This stipulated that anchorages, airfields, radio transmitters and submarine cables remained under British control, and, in fact, this situation remained in force (apart from anchorages) until 1949-1950. Anchorages had been relinquished in 1938 through negotiations with the British government (MacDonald 1972) but the ensuing unfavourable relations with Churchill overshadowed the extent to which the Irish Prime Minister, Eamon de Valera, assiduously adhered to the terms of the Treaty even if these required a slightly biased form of neutrality. -

ST. MARY's COLLEGE C.S.Sp. 2005 and 2006 ANNUALS

ST. MARY’S COLLEGE C.S.Sp. ST. MARY’S COLLEGE ANNUALS 2005 and 2006 Published by ST. MARY’S COLLEGE C.S.Sp., RATHMINES, DUBLIN 6. 2005 and 2006 ANNUALS www.stmarys.ie ST. MARY’S COLLEGE ANNUAL 2006 106th* ACADEMIC YEAR PUBLISHED BY ST. MARY’S COLLEGE CSSp, RATHMINES, DUBLIN 6. A B C D E F G H BOYS IN BLUE A – (l-r) Sean Connaughton, Alan Keane, Rory Sweeney, Ross Church. F – (l-r) Conor Corcoran, John Hannin, Niccolai Schuster. B – Front (l-r) Neal Flynn, Ross Williams. G – (l-r) Brian Roebuck, Ben Connery, Jack O’Donoghue, Behind (l-r) John Jones, Odhrán Byrne, Ronan O’Mahony, Daniel Barnwell, John McCarthy. Sam Wallis, Ian Downey, Eoin Drumm. H – Front (l-r) Michael Scott, Matthew Creedon. C – Front (l-r): Robert Edge, Simon Walsh, Cillian Foynes, Behind (l-r) Cian O’Carroll, Luke Carey. Zach Murray-Golden and Philip Doran. I – (l-r) Cillian O’Donohoe, with Conor Sheridan and Colm Byrne Behind (l-r): Danny Spring, Adam Devereux, John Twomey, (behind), Jack Hogan, Niall McDermott. Sean Cranley, John Vather. J – (l-r) Hugh Lambert, Doug Leddin, David Owen-Mahon, D – Cillian Foynes. Niall Bolger. K E – (l-r) Michael O’Malley, Luke Talbot. K – Thomas O’Reilly. I J Contents Boys in Blue! 136 College Community, Senior School Board of Management and Staff 2005-2006 139 Senior School Roll 2005-2006 140 Senior School Class Photographs 2005-2006 145 That Was The Year That Was 163 6th Year Prizegiving 2005-2006 176 Transition Year 2005-2006 179 Senior School Prizegiving 2005-2006 181 First Year Round-Up 187 The Wiz 2005 188 Obituary – Rory Moore R.I.P. -

Foynes Maintenance Maintenance Dredging of Silts

PROJECT SHEET FOYNES MAINTENANCE DREDGING 2018 SHANNON FOYNES PORT, COUNTY LIMERICK, IRELAND FEATURES PROJECT DESCRIPTION Project Name Foynes Maintenance Dredging 2018 Shannon Foynes Port is a natural deep water harbour on the southern shore of the Shannon Client Shannon Foynes Port Company Limited estuary on the west coast of Ireland. It caters for Contractor Irish Dredging Company Ltd a variety of vessels including bulk and general cargoes and liquid products. Location Foynes, Co. Limerick, Ireland Execution period 2018 The works were for the maintenance dredging of silts from 6 areas within Foynes Harbour. Dredging was carried out by the trailing suction hopper dredger 'Freeway' on a charter rate to bulk dredge material for a fixed period of time. The port's plough boat 'Shannon 1' worked closely with the Freeway ploughing material into the channel and levelling the bed on completion of the dredging. The areas had various design A depths varying between -4.2m and -11.7m CD. The dredged material was discharged at the disposal ground a short distance from the Foynes entrance channel in the River Shannon. The method of working for each 24-hour period A was based on daily surveys, which were A TSHD Freeway working close to the quay performed by the Client's own surveyors. B 'Freeway' dredging in Foynes Harbour C 'Freeway' working close to the quay The licence constraints limited dredging to a 7 day campaign. Working closely with Shannon Foynes Port led to a successful project being completed ahead of schedule and under budget. B C. -

Limerick City and County Council Croom Local Area Plan 2009 – 2015

Limerick City and County Council Croom Local Area Plan 2009 – 2015 (extended for a further 5 years) Amendment to incorporate additional lands at Skagh, Croom, Co. Limerick. Strategic Environmental Assessment Screening, Habitats Directive Assessment Screening Report and Flood Risk Assessment Stage 1 April 2015 1 Contents: SEA Screening: 1.1 Introduction…………………………………………………… p.3 1.2 Screening Statement………………………………………… p.4 1.3 Conclusions…………………………………………………… p.10 AA Screening: 2.1 Introduction…………………………………………………….. p.12 2.2 Screening Matrix………………………………………………..p.14 2.3 Finding of No Significant Effects Matrix…………………… p.18 Flood Risk Assessment: 3.1 Introduction………………………………………………….….p.19 3.2 Flood Risk Identification…………………………………… p.19 3.3 Comments and Overall Conclusions…………………….. p.29 Appendix: Zoning map with proposed amendment 2 SEA/AA Screening Report 1.1 Introduction Croom is a tier 3 population centre in the Limerick County Development Plan 2010- 2016. This is a settlement on a transport corridor. It is located 12 miles to the south west of Limerick and is on the N20 Cork to Limerick National Primary Route. In April 2011 Croom had a population of 1,157, consisting of 591 males and 566 females. The population of pre-school age (0-4) was 87, of primary school going age (5-12) was 153 and of secondary school going age (13-18) was 76. There were 158 persons aged 65 years and over. Having regard to the local population the proposed amendment falls below the mandatory population threshold for Strategic Environmental Assessment, which is currently 5000 people. The zoned area of Croom is 151.07 ha which is below the mandatory area threshold for SEA which is 50km2.