Revised Foynes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

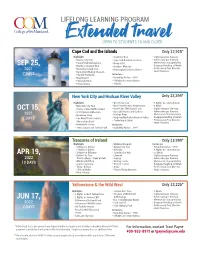

Extended Travel OPEN to STUDENTS 18 and OLDER

LIFELONG LEARNING PROGRAM Extended travel OPEN TO STUDENTS 18 AND OLDER Cape Cod and the Islands Only $2,925* Highlights • Cranberry Bog • Sightseeing per Itinerary • Boston City Tour • Cape Cod National Seashore • Admissions per Itinerary • Faneuil Hall Marketplace • Newport RI • Motorcoach Transportation SEP 25, • Martha’s Vineyard Tour • Breakers Mansion • Baggage Handling at Hotels • Professional Tour Director 2021 • Nantucket Island Visit • New England Lobster Dinner • Nantucket Whaling Museum • Hotel Transfers 7 DAYS • Plimoth Plantation Inclusions • Mayflower II • Roundtrip Airfare – HOU • Plymouth Rock • 6 Nights Accommodations • Provincetown • 9 Meals .................................................................................................................................................... New York City and Hudson River Valley Only $3,399* Highlights • West Point Tour • 6 Nights Accommodations • New York City Tour • New Paltz/Historic Huguenot St. • 8 Meals OCT 15, • Statue of Liberty/Ellis Island • Hyde Park-FDR Historic Site • Sightseeing per Itinerary • 9/11 Memorial/Museum • Boscobel House and Gardens • Admissions per Itinerary 2021 • Broadway Show • Hudson River • Motorcoach Transportation • One World Trade Center/ • Kingston/Manhattan/Hudson Valley • Baggage Handling at Hotels 7 DAYS • Professional Tour Director Observation Deck • Crown Maple Syrup • Hotel Transfers • Rockefeller Center Inclusions • Times Square and Central Park • Roundtrip Airfare – HOU ................................................................................................................................................... -

Transatlantic: the Flying Boats of Foynes

Transatlantic: The Flying Boats of Foynes A Documentary by Michael Hanley Transatlantic: The Flying Boats of Foynes Introduction: She'd come down into the water the very same as a razor blade... barely touch it ‐ you'd hardly see the impression it would make. That was usual, but other times they might hit it very hard... ah yes, they were great days, there's no doubt about it. Poem: I'm sure you still remember the famous flying boats, B.O.A.C., P.A.A. and American Export. With crews - some were small, some tall, some dressed in blue, And in a shade of silvery grey, Export hostess and crew. Narrator: The town of Foynes is situated 15 miles west of Limerick city at the mouth of the River Shannon. Today it is a quietly prosperous port that at first glimpse belies its significance in the history of aviation. 60 years ago the flying boats, the first large commercial aeroplanes ploughed their heavy paths through the rough weather of the transatlantic run to set their passengers down here, on the doorstep of Europe, gateway to a new world. In a time of economic depression and growing international conflict, Foynes welcomed the world in the embrace of the Shannon estuary. "It can't be done!" That was most people's reaction to the idea of flying the Atlantic. After the First War, aircraft could just not perform to the levels needed to traverse the most treacherous ocean in the world. But the glory and the economic rewards for those who succeeded were huge. -

Limerick Timetables

Limerick B A For more information For online information please visit: locallinklimerick.ie Call us at: 069 78040 Email us at: [email protected] Ask your driver or other staff member for assistance Operated By: Local Link Limerick Fares: Adult Return/Single: €5.00/€3.00 Student & Child Return/Single: €3.00/€2.00 Adult Train Connector: €1.50 Student/Child Train Connector: €1.00 Multi Trip Adult/Child: €8.00/€5.00 Weekly Student/Child: €12.00 5 day Weekly Adult: €20.00 6 day Weekly Adult: €25.00 Free Travel Pass holders and children under 5 years travel free Our vehicles are wheelchair accessible Contents Route Page Ballyorgan – Ardpatrick – Kilmallock – Charleville – Doneraile 4 Newcastle West Service (via Glin & Shanagolden) 12 Charleville Child & Family Education Centre 20 Spa Road Kilfinane to Mitchelstown 21 Mountcollins to Newcastle West (via Dromtrasna) 23 Athea Shanagolden to Newcastle West Desmond complex 24 Castlemahon via Ballingarry to Newcastle West - Desmond Complex 25 Castlmahon to Newcastle West - Desmond Complex 26 Ballykenny to Newcastle West- Desmond Complex 27 Shanagolden to Newcastle West - Special Olympics 28 Tournafulla to Newcastle West - Special Olympics 29 Abbeyfeale to Newcastle West - Special Olympics 30 Elton to Hospital 31 Adare to Newcastle West 32 Kilfinny via Adare to Newcastle West 33 Feenagh via Ballingarry to Newcastle West - Desmond Complex 34 Knockane via Patrickswell to Dooradoyle 35 Knocklong to Dooradoyle 36 Rathkeale via Askeaton to Newcastle West to Desmond Complex 37 Ballingarry to -

Irish Marriages, Being an Index to the Marriages in Walker's Hibernian

— .3-rfeb Marriages _ BBING AN' INDEX TO THE MARRIAGES IN Walker's Hibernian Magazine 1771 to 1812 WITH AN APPENDIX From the Notes cf Sir Arthur Vicars, f.s.a., Ulster King of Arms, of the Births, Marriages, and Deaths in the Anthologia Hibernica, 1793 and 1794 HENRY FARRAR VOL. II, K 7, and Appendix. ISSUED TO SUBSCRIBERS BY PHILLIMORE & CO., 36, ESSEX STREET, LONDON, [897. www.genespdf.com www.genespdf.com 1729519 3nK* ^ 3 n0# (Tfiarriages 177.1—1812. www.genespdf.com www.genespdf.com Seventy-five Copies only of this work printed, of u Inch this No. liS O&CLA^CV www.genespdf.com www.genespdf.com 1 INDEX TO THE IRISH MARRIAGES Walker's Hibernian Magazine, 1 771 —-1812. Kane, Lt.-col., Waterford Militia = Morgan, Miss, s. of Col., of Bircligrove, Glamorganshire Dec. 181 636 ,, Clair, Jiggmont, co.Cavan = Scott, Mrs., r. of Capt., d. of Mr, Sampson, of co. Fermanagh Aug. 17S5 448 ,, Mary = McKee, Francis 1S04 192 ,, Lt.-col. Nathan, late of 14th Foot = Nesbit, Miss, s. of Matt., of Derrycarr, co. Leitrim Dec. 1802 764 Kathcrens, Miss=He\vison, Henry 1772 112 Kavanagh, Miss = Archbold, Jas. 17S2 504 „ Miss = Cloney, Mr. 1772 336 ,, Catherine = Lannegan, Jas. 1777 704 ,, Catherine = Kavanagh, Edm. 1782 16S ,, Edmund, BalIincolon = Kavanagh, Cath., both of co. Carlow Alar. 1782 168 ,, Patrick = Nowlan, Miss May 1791 480 ,, Rhd., Mountjoy Sq. = Archbold, Miss, Usher's Quay Jan. 1S05 62 Kavenagh, Miss = Kavena"gh, Arthur 17S6 616 ,, Arthur, Coolnamarra, co. Carlow = Kavenagh, Miss, d. of Felix Nov. 17S6 616 Kaye, John Lyster, of Grange = Grey, Lady Amelia, y. -

Limerick Walking Trails

11. BALLYHOURA WAY 13. Darragh Hills & B F The Ballyhoura Way, which is a 90km way-marked trail, is part of the O’Sullivan Beara Trail. The Way stretches from C John’s Bridge in north Cork to Limerick Junction in County Tipperary, and is essentially a fairly short, easy, low-level Castlegale LOOP route. It’s a varied route which takes you through pastureland of the Golden Vale, along forest trails, driving paths Trailhead: Ballinaboola Woods Situated in the southwest region of Ireland, on the borders of counties Tipperary, Limerick and Cork, Ballyhoura and river bank, across the wooded Ballyhoura Mountains and through the Glen of Aherlow. Country is an area of undulating green pastures, woodlands, hills and mountains. The Darragh Hills, situated to the A Car Park, Ardpatrick, County southeast of Kilfinnane, offer pleasant walking through mixed broadleaf and conifer woodland with some heathland. Directions to trailhead Limerick C The Ballyhoura Way is best accessed at one of seven key trailheads, which provide information map boards and There are wonderful views of the rolling hills of the surrounding countryside with Galtymore in the distance. car parking. These are located reasonably close to other services and facilities, such as shops, accommodation, Services: Ardpatrick (4Km) D Directions to trailhead E restaurants and public transport. The trailheads are located as follows: Dist/Time: Knockduv Loop 5km/ From Kilmallock take the R512, follow past Ballingaddy Church and take the first turn to the left to the R517. Follow Trailhead 1 – John’s Bridge Ballinaboola 10km the R517 south to Kilfinnane. At the Cross Roads in Kilfinnane, turn right and continue on the R517. -

1911 Census, Co. Limerick Householder Index Surname Forename Townland Civil Parish Corresponding RC Parish

W - 1911 Census, Co. Limerick householder index Surname Forename Townland Civil Parish Corresponding RC Parish Wade Henry Turagh Tuogh Cappamore Wade John Cahernarry (Cripps) Cahernarry Donaghmore Wade Joseph Drombanny Cahernarry Donaghmore Wakely Ellen Creagh Street, Glin Kilfergus Glin Walker Arthur Rooskagh East Ardagh Ardagh Walker Catherine Blossomhill, Pt. of Rathkeale Rathkeale (Rural) Walker George Rooskagh East Ardagh Ardagh Walker Henry Askeaton Askeaton Askeaton Walker Mary Bishop Street, Newcastle Newcastle Newcastle West Walker Thomas Church Street, Newcastle Newcastle Newcastle West Walker William Adare Adare Adare Walker William F. Blackabbey Adare Adare Wall Daniel Clashganniff Kilmoylan Shanagolden Wall David Cloon and Commons Stradbally Castleconnell Wall Edmond Ballygubba South Tankardstown Kilmallock Wall Edward Aughinish East Robertstown Shanagolden Wall Edward Ballingarry Ballingarry Ballingarry Wall Ellen Aughinish East Robertstown Shanagolden Wall Ellen Ballynacourty Iveruss Askeaton Wall James Abbeyfeale Town Abbeyfeale Abbeyfeale Wall James Ballycullane St. Peter & Paul's Kilmallock Wall James Bruff Town Bruff Bruff Wall James Mundellihy Dromcolliher Drumcolliher, Broadford Wall Johanna Callohow Cloncrew Drumcollogher Wall John Aughalin Clonelty Knockderry Wall John Ballycormick Shanagolden Shanagolden & Foynes Wall John Ballygubba North Tankardstown Kilmallock Wall John Clashganniff Shanagolden Shanagolden & Foynes Wall John Ranahan Rathkeale Rathkeale Wall John Shanagolden Town Shanagolden Shanagolden & Foynes -

Fonsie Mealy Auctioneers Rare Books & Collectors' Sale December 9Th & 10Th, 2020

Rare Books & Collectors’ Sale Wednesday & Thursday, December 9th & 10th, 2020 RARE BOOKS & COLLECTORS’ SALE Wednesday & Thursday December 9th & 10th, 2020 Day 1: Lots 1 – 660 Day 2: Lots 661 - 1321 At Chatsworth Auction Rooms, Chatsworth Street, Castlecomer, Co. Kilkenny Commencing at 10.30am sharp Approx. 1300 Lots Collections from: The Library of Professor David Berman, Fellow Emeritus, T.C.D.; The Library of Bernard Nevill, Fonthill; & Select Items from other Collections to include Literature, Manuscripts, Signed Limited Editions, Ephemera, Maps, Folio Society Publications, & Sporting Memorabilia Lot 385 Front Cover Illustration: Lot 1298 Viewing by appointment only: Inside Front Cover Illustration: Lot 785 Friday Dec. 4th 10.00 – 5.00pm Inside Back Cover Illustration: Lot 337 Back Cover Illustration: Lot 763 Sunday Dec. 6th: 1.00 – 5.00 pm Monday Dec. 7th: 10.00 – 5.00 pm Online bidding available: Tuesday Dec. 8th: 10.00 – 5.00 pm via the-saleroom.com (surcharge applies) Bidding & Viewing Appointments: Via easyliveauction.com (surcharge applies) +353 56 4441229 / 353 56 4441413 [email protected] Eircode: R95 XV05 Follow us on Twitter Follow us on Instagram Admittance strictly by catalogue €20 (admits 2) @FonsieMealy @fonsiemealyauctioneers Sale Reference: 0322 PLEASE NOTE: (We request that children do not attend viewing or auction.) Fonsie Mealy Auctioneers are fully Covid compliant. Chatsworth Auction Rooms, Chatsworth St., Castlecomer, Co. Kilkenny, Ireland fm Tel: +353 56 4441229 | Email: [email protected] | Website: www.fonsiemealy.ie PSRA Registration No: 001687 Design & Print: Lion Print, Cashel. 062-61258 fm Fine Art & R are Books PSRA Registration No: 001687 Mr Fonsie Mealy F.R.I.C.S. -

Section 482, Taxes Consolidation Act, 1997

List of approved buildings/gardens open to the public in 2019 Section 482 Taxes Consolidation Act 1997 1 Carlow Borris House Borris, Co. Carlow Morgan Kavanagh Tel: 087-2454791 www.borrishouse.com Open: Feb 9-17, 12 noon-5pm, Apr 19-22, May 1-31, June 1-30, July 1-31, Aug 1-31, Sept 1-30, 11am-6pm, Oct 27-31, 4 pm-7pm, Dec 1, 7-8, 14-15, 21-22, 2pm-6pm Fee: house & garden adult €10, child €5, OAP/student €9, garden adult €6, child €3, OAP/student €5, family and group discounts also available. Huntington Castle Clonegal, Co. Carlow Postal address: Huntington Castle, Enniscorthy, Co. Wexford Alexander Durdin Robertson Tel: 086-0282266 www.huntingtoncastle.com Open: Feb 9-17, 12 noon-5 pm, Apr 19-22, May 1-31, June 1-30, July 1-31, Aug 1- 31, Sept 1-30, 11am-6pm, Oct 27-31, 4pm-7pm, Dec 1, 7-8, 14-15, 21-22, 2pm-6pm Fee: house/garden, adult €10, OAP/student €9, child €5 garden, adult €6, OAP/student €5, child €3, family and group discounts available The Old Rectory Killedmond, Borris, Co. Carlow. Mary White Tel: 087-2707189 [email protected] Open: July 1-31, Aug 1-31, 9am-1pm Fee: adult €10, OAP/student €6, child free The Old Rectory Lorum Kilgreaney, Bagenalstown, Co. Carlow Bobbie & Rebecca Smith Tel: 059-9775282 www.lorum.com (Tourist Accommodation Facility) Open: Feb 1-November 30 Cavan Cabra Castle (Hotel) Kingscourt, Co. Cavan Howard Corscadden. Tel: 042-9667030 www.cabracastle.com Open: all year, except Dec 24, 25, 26, 11am-12 midnight Fee: Free 2 Corravahan House & Gardens Corravahan, Drung, Ballyhaise, Co. -

ORIGINAL BUREAUOFMILITARYHISTORY1913-21 BUROSTAIREMILEATA1913-21 No. W.S. 1,272 ROINN COSANTA. BUREAU of MILITARY HISTORY, 1913

BUREAUOFMILITARYHISTORY1913-21 BUROSTAIREMILEATA1913-21 No. W.S. 1,272 ORIGINAL ROINN COSANTA. BUREAU OF MILITARY HISTORY, 1913-21. STATEMENT BY WITNESS. DOCUMENT NO. W.S. 1272 Witness James Collins, T.D., Convent Terrace, Abbeyfeale, Co. Limerick. Identity. Captain Abbeyfeale Company; Vice O/C. Abbeyfeale Battalion; Brigade Adjutant West Limerick Brigade. Subject. Abbeyfeale Irish Company Volunteers, Co. Limerick, l9l5-192l. Conditions, if any, Stipulated by Witness. Nil File No. S.2564 Form B.S.M.2 1913-21 BUREAUOFMILITARYHISTORY BUROSTAIREMILEATA1913-21 No. W.S. 1,272 STATEMENT OF JAMES COLLINS, T.D., ORIGINAL Convent Terrace, Abbeyfeale, Co. Limerick. I was born in the parish of Abbeyfeale on the 31st October, 1900, and was one of a family of three boys and three girls. My parents, who were farmers, sent me to the local national school until I was fourteen years of age, after which I attended a private school run by a man named Mr. Danaher. While attending the private school, I became an apprentice to a chemist in the town of Abbeyfeale whose name was Richard B. Woulfe. After completing my apprenticeship, I was retained in his employment for some years until I was forced to go on the run during the Black and Tan terror. Mr. Woulfe's wife was Miss Cathie Colbert, sister of Con Colbert (executed after Easter Week 1916) and James Colbert, and cousin of Michael Colbert who later became Brigade Vice 0/C, West Limerick Brigade. The Woulfe's were great supporters of the Irish independence movement and their shop and house, from the earliest days of the movement, became a meeting place for men like Con Colbert, Captain Ned Daly and others who later figured perminently in the fight for freedom. -

Rosse Papers Summary List: 17Th Century Correspondence

ROSSE PAPERS SUMMARY LIST: 17TH CENTURY CORRESPONDENCE A/ DATE DESCRIPTION 1-26 1595-1699: 17th-century letters and papers of the two branches of the 1871 Parsons family, the Parsonses of Bellamont, Co. Dublin, Viscounts Rosse, and the Parsonses of Parsonstown, alias Birr, King’s County. [N.B. The whole of this section is kept in the right-hand cupboard of the Muniment Room in Birr Castle. It has been microfilmed by the Carroll Institute, Carroll House, 2-6 Catherine Place, London SW1E 6HF. A copy of the microfilm is available in the Muniment Room at Birr Castle and in PRONI.] 1 1595-1699 Large folio volume containing c.125 very miscellaneous documents, amateurishly but sensibly attached to its pages, and referred to in other sub-sections of Section A as ‘MSS ii’. This volume is described in R. J. Hayes, Manuscript Sources for the History of Irish Civilisation, as ‘A volume of documents relating to the Parsons family of Birr, Earls of Rosse, and lands in Offaly and property in Birr, 1595-1699’, and has been microfilmed by the National Library of Ireland (n.526: p. 799). It includes letters of c.1640 from Rev. Richard Heaton, the early and important Irish botanist. 2 1595-1699 Late 19th-century, and not quite complete, table of contents to A/1 (‘MSS ii’) [in the handwriting of the 5th Earl of Rosse (d. 1918)], and including the following entries: ‘1. 1595. Elizabeth Regina, grant to Richard Hardinge (copia). ... 7. 1629. Agreement of sale from Samuel Smith of Birr to Lady Anne Parsons, relict of Sir Laurence Parsons, of cattle, “especially the cows of English breed”. -

PAN Ilher/CAN WORLD A/Rwat Y' ~ S;S/~M Of1j,{'(--7Fr1ilf Czjjt'rs

~ PAA PAA PAN AMERJCAN WOHLD AIRWAYS IN IRELAND HISTORY HE f,rst il\spirin~ c1Llph'r in .til c history of "vi<ttion in Ircland will T always h,· 11flk"L1 closcly WI' h the name o[ PUll Anlerlcan \Vorld Airways. U n Ihe afternoon oi July (;th, 19.17, while cmwds lin(:J the mads leading to the Co. Limerick village of F ('ynes ann ncw,pal"'rmr:-n lllSTOHY representing the press of th" Wo rld were there to retell the story, the giant Pan Anwrican Airways Sikor',ky Clippcr III hlawn in acco;s the Atlantic ,~nd landed the quiet waters of th,. Shannon amid gn-"t. ORGANJZATION II" chN:r!; fmrn til(' crowds. This was ;hc f,rst cornm"ccial aircraft ever 10 arrive in lrchnn from the l lnil<'oi St.ates ,)f .'\mericCl. Not onl" was th:, PEIISONNEL achi"vern('llt of this Clipper hif: news ill lr('\a nd, hnt it ranI( ';). nl1le pf prid" in the h eart o f e\'ITV Trish n"me in the United States. The crllwd haJ every rcason to cheCI. fnr Captain lIarold Cra),. Pilot of thc Clippcl. han lJriclg..d the Atlantic in what was then thc remarkable tillle of 11 hou r" ane! 40 Illinutcs. 'filat was" memorablc <lay at Foynt';. fnr only the previous cvcning the Imperial Airways Flying Boat' 'Caledonia" look ,) fl on the lirst westbound lIight to BotwO()[I. N"wfoundlantl, tyill/-: th(: kllot in mid-Atlantic wh~n C;ll'lain \Vilcockson and Captaill Cray of ihp. (lip!'('r gr,' c\cd tach other by radio Io'\P.l'hone ut a I\t'ight of ;limost 'J .ooo fCd. -

Information and Services for Older People Across Limerick

INFORMATION AND SERVICES FOR OLDER PEOPLE ACROSS LIMERICK 1 INFORMATION AND SERVICES FOR OLDER PEOPLE ACROSS LIMERICK CONTENTS USEFUL NUMBERS .............................................................................3 SECTION 1: BEING POSITIVE: ACTIVITIES INVOLVING OLDER PEOPLE Active Retired Group .............................................................................4 PROBUS ..............................................................................................5 Courses and Activities ........................................................................5 General Course Providers ....................................................................5 Computer Skills Courses .....................................................................6 Men’s Sheds .......................................................................................7 Women’s Groups ............................................................................... 9 Get Togethers and Craft Groups .......................................................10 Cards .................................................................................................10 Bingo .................................................................................................11 Music and Dancing ............................................................................12 Day Centres ......................................................................................13 Libraries ............................................................................................18