Henrietta Porter in the Television Series Trackdown

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BILL COSBY Biography

BILL COSBY Biography Bill Cosby is, by any standards, one of the most influential stars in America today. Whether it be through concert appearances or recordings, television or films, commercials or education, Bill Cosby has the ability to touch people’s lives. His humor often centers on the basic cornerstones of our existence, seeking to provide an insight into our roles as parents, children, family members, and men and women. Without resorting to gimmickry or lowbrow humor, Bill Cosby’s comedy has a point of reference and respect for the trappings and traditions of the great American humorists such as Mark Twain, Buster Keaton and Jonathan Winters. The 1984-92 run of The Cosby Show and his books Fatherhood and Time Flies established new benchmarks on how success is measured. His status at the top of the TVQ survey year after year continues to confirm his appeal as one of the most popular personalities in America. For his philanthropic efforts and positive influence as a performer and author, Cosby was honored with a 1998 Kennedy Center Honors Award. In 2002, he received the Presidential Medal of Freedom, America’s highest civilian honor, was the 2009 recipient of the Mark Twain Prize for American Humor and the Marian Anderson Award. The Cosby Show - The 25th Anniversary Commemorative Edition, released by First Look Studios and Carsey-Werner, available in stores or online at www.billcosby.com. The DVD box set of the NBC television hit series is the complete collection of one of the most popular programs in the history of television, garnering 29 Emmy® nominations with six wins, six Golden Globe® nominations with three wins and ten People’s Choice Awards. -

TV Club Newsletter; April 4-10, 1953

COVERING THE TV BEAT: GOVERNMENT RESTRICTIONS ON COLOR TV ARE BEING LIFTED. How- ever, this doesn't bring color on your screen any closer. Color TV will arrive after extensive four-month field tests of the system recently developed through the pooled research of major set manufacturers; after the FCC studies and ap- proves the new method ; and after the many more months it will take to organize factory production of sets and to in- stall color telecasting equipment. TED MACK AND THE ORIGINAL AMATEUR HOUR RETURN to your TV screen April 25 to be seen each Saturday from 8:30 - 9 p.m. It will replace the second half of THE ALL-STAR REVUE, which goes off. WHAM-TV and WBEN-TV have indicated that they will carry the show. THREE DIMENSIONAL TV is old stuff to the Atomic Energy Commission. Since 1950, a 3D TV system, developed in coop- eration with DuMont, has been in daily use at the AEC's Argonne National Laboratories near Chicago. It allows technicians to watch atomic doings closely without danger from radiation. TV WRESTLERS ARE PACKING THEM IN AT PHILADELPHIA'S MOVIE houses where they are billed as added stage attractions with simulated TV bouts. SET-MAKERS PREDICT that by the end of the year 24-inch sets will constitute 25% of production. FOREIGN INTRIGUE is being released for European TV distri- bution with one version in French and the other with Ger- man subtitles. "I LOVE LUCY", WILL PRESENT "RICKY JR.", the most celebrat- ed TV baby, in its forthcoming series now being filmed in Hollywood. -

One Soldier Calls on Friends from Hazzard County to Raise Soldiers

Iraqis practice combat life-saving Regatta makes a splash at JBB Iraqi children receive flip-flops Page 3 Page 5 Pages 8&9 Proudly serving the finest expeditionary service members throughout Iraq Vol. 5, Issue 10 June 8, 2011 Hazzard Ahead U.S. Army photo by Sgt. Benjamin D. Green U.S. Army photo by Sgt. Benjamin D. Green Spc. Bobby Scott (second from right), a petroleum supply specialist with the 310th Expeditionary Sustainment Command and a Mooresville, Ind., native, shares information with fellow Soldiers Aug. 10, 2010, about his “Dukes of Hazzard” General Lee and Sheriff Rosco car replicas. Scott, who tours the coun- try with his cars in support of “Dukes of Hazzard” fan events, brought them to a 310th ESC family event at Fort Benjamin Harrison, Ind. STORY BY sion. For the next hour of his life, he has no petroleum supply specialist with the 310th One Soldier calls SGT. FELICYA L. ADAMS worries, and nothing that he would rather do Expeditionary Sustainment Command and a EXPEDITIONARY TIMES STAFF except devote his time to that one particular Mooresville, Ind., native. on friends from television show. The show would come on at Scott grew up to become an avid collector JOINT BASE BALAD, Iraq – Like clock- 8 o’ clock, and it was a household occasion of “Dukes of Hazzard” memorabilia and Hazzard County work every Friday, a little for the little boy and his family. It all started now owns a replica General Lee and Sheriff boy returns to his routine. He with a car called the General Lee. -

![I1470 I Spy (9/15/1965-9/9/1968) [Tv Series]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1375/i1470-i-spy-9-15-1965-9-9-1968-tv-series-561375.webp)

I1470 I Spy (9/15/1965-9/9/1968) [Tv Series]

I1470 I SPY (9/15/1965-9/9/1968) [TV SERIES] Series summary: Spy/adventure series which follows the operations of undercover agents Kelly Robinson (Culp) and Alexander Scott (Cosby). Kelly travels the globe as an international tennis champion, with Scott as his trainer, battling the enemies of the U.S. Happy birthday… everybody (2/26/1968) Credits: director, Earl Bellamy; writers, David Friedkin, Morton Fine Cast: Bill Cosby, Robert Culp, Gene Hackman Summary: Robinson and Scott spot Frank Hunter (Hackman), an escaped mental patient who has promised to track down and kill the retired agent responsible for arresting him after his failure to sabotage an arms shipment being sent to Vietnam. Tatia (11/17/1965) Credits: director, David Friedkin ; writer, Robert Lewin Cast: Bill Cosby, Robert Culp, Laura Devon Summary: Scott becomes involved in the disappearance of three agents bound for Vietnam when a fourth is murdered in his hotel room while a beautiful photographer (Devon) distracts Kelly. War lord (2/1/1967) Credits: director, Alf Cjellin ; writer, Robert Culp Cast: Bill Cosby, Robert Culp, Jean Marsh, Cecil Parker Summary: Set in contemporary Laos. Katherine Faulkner (Marsh), a British aid worker, is kidnapped when the village where she is working is attacked. Her father, the wealthy and politically connected Sir Guy Faulkner, receives a ransom demand from Chuang-Tzu, a Laotian war lord. The charitable organization which sponsored Katherine filmed the attack and has used it to solicit millions in donations, leading Kelly Robinson to suspect the attack may have been a hoax. One of the fundraisers admits to the hoax, but asserts the kidnapping was real. -

Dukes of Hazzard 7

Dukes of hazzard 7 click here to download This is my Tribute to the greatest TV serie. The Dukes Of Hazzard with the amazing cast: Denver Pyle as Uncle. While driving through Osage, the most feared county around ruled by the mean Colonel Claiborne, Bo and. This is a list of episodes for the CBS action-adventure/comedy series The Dukes of Hazzard. The show ran for seven seasons and a total of episodes. Many of the episodes followed a similar structure: "out-of-town crooks pull a robbery, Duke boys blamed, spend the rest of the hour clearing their names, the Episodes · Season 2 (–80) · Season 3 (–81) · Season 4 (–82). Action · Bo and Luke are hired to haul what they think is a shipment of shock absorbers. Actually, they've been duped into driving a rolling casino. www.doorway.ru: The Dukes of Hazzard: Season 7: Paul R. Picard, Tom Wopat, John Schneider, Catherine Bach, Denver Pyle, Sonny Shroyer, Ben Jones, James Best, Sorrell Booke, Waylon Jennings: Movies & TV. Preview and download your favorite episodes of The Dukes of Hazzard, Season 7, or the entire season. Buy the season for $ Episodes start at $ The Dukes of Hazzard Season 7. Get ready for the action - Hazzard County style - as Luke and Bo Duke and their beautiful cousin Daisy Duke push the good fight just a little more than the law will allow. With a knack for getting into trouble there's racing cars, flying cars, tumbling cars and plenty of good old-fashioned country. The seventh and final season of Dukes of Hazzard finds the familiar cast back in harness, with the exception of Don Pedro Colley in the recurring role of Chickasaw County Sheriff Ed Little. -

Regular Meeting of the Board of Port Commissioners Of

board of Port Catirr# 14"1""- -Re"1117 SetnalrY REGULAR MEETING OF THE BOARD OF PORT COMMISSIONERS OF THE CITY OF OAKLAND The meeting was held on Wednesday, January 7, 1970 at the hour of 2:00 p.m. in the office of the Board, Room 376, 66 Jack London Square, President Walters presiding, due written notice having been given members of the Board. Commissioners present: Commissioners Bilotti, Gainor, Mortensen, Tripp and President Walters - 5 Commissioners absent: Commissioners Berkley and Soda - 2 Also present were the Executive Director; Assistant Exe- cutive Director; Port Attorney; Chief Engineer; Director of Aviation; Public Relations Director; Secretary of the Board; and for a portion of the meeting Deputy Port Attorney John E. Nolan; Traffic Manager and Manager, Marine Terminals Department; Port Supervising Engineer Roy Clark; Supervising Airport Traffic Representative Fernand E. Dubois; and Semi-skilled Laborer Edward H. Dillinger. Outgoing President Robert E. Mortensen presented the new President, William Walters, with the gavel of his office and President Walters presented Commissioner Mortensen with a desk set in recognition of his term as President of the Board. The reading of the minutes of the regular meeting of December 17, and the adjourned regular meeting of December 22, 1969, were approved as written and ordered filed. The Director of Aviation introduced Mr. Fernand E. Dubois, Supervising Airport Traffic Representative, to the Board, and First Vice President Tripp presented Mr. Dubois with a pin denoting 15 years ser- vice to the Port. Port Supervising Engineer Roy Clark introduced Mr. Edward H. Dillinger, Semi-skilled Laborer, to members of the Board, and Com- missioner Mortensen presented Mr. -

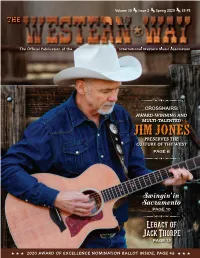

Spring 2020 $5.95 THE

Volume 30 Issue 2 Spring 2020 $5.95 THE The Offi cial Publication of the International Western Music Association CROSSHAIRS: AWARD-WINNING AND MULTI-TALENTED JIM JONES PRESERVES THE CULTURE OF THE WEST PAGE 6 Swingin’ in Sacramento PAGE 10 Legacy of Jack Thorpe PAGE 12 ★ ★ ★ 2020 AWARD OF EXCELLENCE NOMINATION BALLOT INSIDE, PAGE 46 ★ ★ ★ __WW Spring 2020_Cover.indd 1 3/18/20 7:32 PM __WW Spring 2020_Cover.indd 2 3/18/20 7:32 PM 2019 Instrumentalist of the Year Thank you IWMA for your love & support of my music! HaileySandoz.com 2020 WESTERN WRITERS OF AMERICA CONVENTION June 17-20, 2020 Rushmore Plaza Holiday Inn Rapid City, SD Tour to Spearfish and Deadwood PROGRAMMING ON LAKOTA CULTURE FEATURED SPEAKER Virginia Driving Hawk Sneve SESSIONS ON: Marketing, Editors and Agents, Fiction, Nonfiction, Old West Legends, Woman Suffrage and more. Visit www.westernwriters.org or contact wwa.moulton@gmail. for more info __WW Spring 2020_Interior.indd 1 3/18/20 7:26 PM FOUNDER Bill Wiley From The President... OFFICERS Robert Lorbeer, President Jerry Hall, Executive V.P. Robert’s Marvin O’Dell, V.P. Belinda Gail, Secretary Diana Raven, Treasurer Ramblings EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR Marsha Short IWMA Board of Directors, herein after BOD, BOARD OF DIRECTORS meets several times each year; our Bylaws specify Richard Dollarhide that the BOD has to meet face to face for not less Juni Fisher Belinda Gail than 3 meetings each year. Jerry Hall The first meeting is usually in the late January/ Robert Lorbeer early February time frame, and this year we met Marvin O’Dell Robert Lorbeer Theresa O’Dell on February 4 and 5 in Sierra Vista, AZ. -

Moving on – Or at Least Trying To

Looking for a way to keep up with local news, school happenings, sports events and more? 2 x 2" ad 2 x 2" ad We’ve got you covered! September 8 - 14, 2017 waxahachietx.com A M S E C A B S E R J A V A H 2 x 3" ad C E K X R O P R F R A N K C U Your Key I J E E M L M E I H E M Q U A To Buying B A L F E C R P J A Z A U L H A S T R N I O K R S F E R L A and Selling! 2 x 3.5" ad K E O A A B F L E O P X C O W H P N L H S R I L H M K E D A B A C F O G Z I R S O I P E B X R U R P N Z F A R K V S N A D A I N E C N B N N A E A E R A T N M T O G E K U N H L A W T E N E M E I Z I H G A I R Z U D A C L M D A N U H K J A R M B E I A R E U E R O G E R E A A R J X P F H K M B E Z S S “Outlander” on Starz Moving on – (Words in parentheses not in puzzle) Claire (Randall Fraser) (Caitriona) Balfe (Battle of) Culloden Place your classified Solution on page 13 Jamie (Fraser) (Sam) Heughan Separated ad in the Waxahachie Daily 2 x 3" ad Frank (Randall) (Tobias) Menzies Haunted Light, Midlothian1 xMirror 4" ad and Brianna (Randall) (Sophie) Skelton Compromise or at least Ellis County Trading Post! Word Search Roger (Wakefield) (Richard) Rankin Hope Call (972) 937-3310 © Zap2it trying to Sam Heughan stars in “Outlander,” which 2 x 3.5" ad begins its third season Sunday on Starz. -

Journalism 375/Communication 372 the Image of the Journalist in Popular Culture

JOURNALISM 375/COMMUNICATION 372 THE IMAGE OF THE JOURNALIST IN POPULAR CULTURE Journalism 375/Communication 372 Four Units – Tuesday-Thursday – 3:30 to 6 p.m. THH 301 – 47080R – Fall, 2000 JOUR 375/COMM 372 SYLLABUS – 2-2-2 © Joe Saltzman, 2000 JOURNALISM 375/COMMUNICATION 372 SYLLABUS THE IMAGE OF THE JOURNALIST IN POPULAR CULTURE Fall, 2000 – Tuesday-Thursday – 3:30 to 6 p.m. – THH 301 When did the men and women working for this nation’s media turn from good guys to bad guys in the eyes of the American public? When did the rascals of “The Front Page” turn into the scoundrels of “Absence of Malice”? Why did reporters stop being heroes played by Clark Gable, Bette Davis and Cary Grant and become bit actors playing rogues dogging at the heels of Bruce Willis and Goldie Hawn? It all happened in the dark as people watched movies and sat at home listening to radio and watching television. “The Image of the Journalist in Popular Culture” explores the continuing, evolving relationship between the American people and their media. It investigates the conflicting images of reporters in movies and television and demonstrates, decade by decade, their impact on the American public’s perception of newsgatherers in the 20th century. The class shows how it happened first on the big screen, then on the small screens in homes across the country. The class investigates the image of the cinematic newsgatherer from silent films to the 1990s, from Hildy Johnson of “The Front Page” and Charles Foster Kane of “Citizen Kane” to Jane Craig in “Broadcast News.” The reporter as the perfect movie hero. -

PD TV Comedy

TV Comedy These particular episodes are in the public domain in the USA. All shows run 26 to 30 minutes unles noted. Some include original commercials. Note: The “Volumes” indicate how the episodes are sold 4-to-a-disc on DVD-R. BetaSP and DVCam masters are sold per episode and are not limited to these groupings. 2) Adventures of Ozzie & Harriet -- 30 discs = 113 shows 7) The Jack Benny Show -- 6 discs = 24 episodes Bonus disc -- Jack Benny Visits Walt Disney 9) I Married Joan -- 6 discs = 24 episodes 11) The Beverly Hillbillies -- 13 discs = 52 episodes 14) George Burns and Gracie Allen -- 3 discs = 13 episodes 15) The Lucy Show -- 7 discs = 30 episodes 17) The Red Skelton Show -- 5 discs = 20 episodes 19) Private Secretary -- 4 discs = 16 episodes 21) Colgate Comedy Hour (with Abbott and Costello) -- 5 discs with 10 hour shows 22) Trouble With Father (The Stu Irwin Show) -- 5 discs / 20 episodes 24) The Bob Cummings Show (Love That Bob) -- 5 discs = 20 shows 26) Petticoat Junction -- 5 discs / 20 shows 28) Christmas TV Shows -- 6 discs / 24 shows 30) My Little Margie -- 6 discs / 24 shows Ozzie & Harriet Shows -- The shows that run 28-29 min. contain the original commercials. The shorter shows do not have commer- cials. Ricky sings in some episodes that are not noted. Vol. 1 SUGGESTION BOX: Ozzie builds a suggestion box so each of the family can write down how they feel about the others. Original air date 11/20/53. 29:22 THE LAW CLERK: Dave wants to get a job as a law clerk based on his own merit, but finds that everyone is out to help him. -

CBS, Rural Sitcoms, and the Image of the South, 1957-1971 Sara K

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2013 Rube tube : CBS, rural sitcoms, and the image of the south, 1957-1971 Sara K. Eskridge Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Eskridge, Sara K., "Rube tube : CBS, rural sitcoms, and the image of the south, 1957-1971" (2013). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3154. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3154 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. RUBE TUBE: CBS, RURAL SITCOMS, AND THE IMAGE OF THE SOUTH, 1957-1971 A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of History by Sara K. Eskridge B.A., Mary Washington College, 2003 M.A., Virginia Commonwealth University, 2006 May 2013 Acknowledgements Many thanks to all of those who helped me envision, research, and complete this project. First of all, a thank you to the Middleton Library at Louisiana State University, where I found most of the secondary source materials for this dissertation, as well as some of the primary sources. I especially thank Joseph Nicholson, the LSU history subject librarian, who helped me with a number of specific inquiries. -

Hot Charts – 1958

JANUARY HOT CHART JANUARY 31 OH JULIE (95) 48 FASCINATION (31) Cresccndos Jane Morgan w-tro (Hasco €005) (Kapp 191) JANUARY 32 OEDE DINAH (—) 49 ANGEL SHILE (—) Frankie Avalon a-pd Nat "King" Cole a-nr (Chancellor 1011) (Capitol 3860} 33 TEAR DROPS (28) 50 A VERY SPECIAL LOVE (49) 1 AT IKE HOP (I) 16 JAILHOUSE ROCK (4) Lee Andrews/Hearts Johnny Nash a/arr-dc Danny and the Juniors a-as Elvis Presley (Chess 1675/Argo 1000) (ABC-Paramount 9874) (Singular 711/ABC-Par. 9871) (RCA Victor 47-7035) 34 ROCK & ROLL MUSIC (13) 51 FOR SENTIMENTAL REASONS (59) 2 GREAT BALIS OF f IRE (5) 1? SHORT SHORTS (—) Chuck Berry Sam Cooke Jerry Lee Lewis Royal Teens (Chess 1671) (Keen 34002) (Sun 281) (Power 215/A0C-Par. 9BB2) 35 MAYBE (—) 52 I'M AVAILABLE (25) 3 PEGGY SUE (7) 18 WHY DON'T THEY UNDERSTAND (17) Chantels Margie Rayburn Buddy Holly George Hamilton IV a/arr-dc (End 1005) (Liberty 55102) (Coral 61885) (ABC-Paramount 9862) 36 8E-BOP BABY (16) S3 YELLOW DOG BLUES (xxx) 4 GET A JOB (KXK) 19 ALL THE WAY (10) Ricky Kelson Joe Darensbourg Si Ihouettes Frank Sinatra a-nr (Imperial 5463) (Lark 452) (Junior 391/Ember 1029) (Capitol 3793} 37 MY SPECIAL ANGEL (15) 54 TELt HER YOU LOVE HER (—) 5 APRIL LOVE (3) 20 OH. 60Y! (23) Bobby Helms o-aks Frank Sinatra a-nr Pat Boone a-bv Crickets (Decca 30423) (Capitol 3859) (Dot 15660) (Brunswick 55035) 38 YOU ARE HY OESTIMY (—) 55 HONEYCOMB (29) 6 THE STROLL (53) 21 BUZZ-BUZZ-BUZZ (27) Paul Anka orr/c-dc Jlmmle Rodgers e-hp Diamonds ts-kc Hollywood Flames (ABC-Paramount 9880) (Roulette 401S) (Mercury 71242) (Ebb 119)