Tracking Chinese Perceptions of Vietnam's Relations with China And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

China Seeks to Dominate Off-Shore Energy Resources in the South and East China Seas by John R

International Association for Energy Economics | 17 China Seeks to Dominate Off-Shore Energy Resources in the South and East China Seas By John R. Weinberger* On May 2, 2014, without announcement, Chinese vessels floated China National Offshore Oil Corp.’s (CNOOC) state-of-the-art deep water drilling rig into Vietnamese waters and began sea floor drilling op- erations for natural gas. The location of the rig - within Vietnam’s 200 nautical mile exclusive economic zone (EEZ) and only 17 nautical miles from Triton Island in the South China Sea, one of the Paracel Islands that is claimed by Vietnam, China, and Taiwan – was unmistakably set up in maritime territory claimed by Vietnam. The Vietnamese Foreign Minister called the move a violation of Vietnamese sov- ereignty. The U.S. State Department described the move as “provocative.” The deployment of China’s first and only home-grown deep-water semisubmersible drilling rig in such a brazen manner illustrates the value that China places on Asia-Pacific off-shore oil and gas resources and the lengths that China will go to assert control over seabed hydrocarbons beneath the far western Pacific Ocean. China’s Quest for Asia-Pacific Energy Resources Driven by Overall Growth in Energy Demand Fossil fuels are the lifeblood of China’s economy. Affordable, reliable sources of crude oil enable China’s transportation sector to grow and thrive. Natural gas is becoming a cornerstone to China’s elec- tric power capacity and an alternative transportation fuel. China’s remarkable economic growth over the past three decades is matched by an insatiable thirst for oil. -

Freedom of Navigation in the South China Sea a Practical Guide

Freedom of Navigation in the South China Sea A Practical Guide Eleanor Freund SPECIAL REPORT JUNE 2017 Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs Harvard Kennedy School 79 JFK Street Cambridge, MA 02138 www.belfercenter.org Publication design and illustrations by Andrew Facini Cover photo: United States. Central Intelligence Agency. The Spratly Islands and Paracel Islands. Scale 1:2,000,000. Washington, D.C.: Central Intelligence Agency, 1992. Copyright 2017, President and Fellows of Harvard College Printed in the United States of America Freedom of Navigation in the South China Sea A Practical Guide Eleanor Freund SPECIAL REPORT JUNE 2017 About the Author Eleanor Freund is a Research Assistant at Harvard Kennedy School’s Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs. She studies U.S. foreign policy and security issues, with a focus on U.S.-China relations. Email: [email protected] Acknowledgments The author is grateful to James Kraska, Howard S. Levie Professor of International Law at the U.S. Naval War College, and Julian Ku, Maurice A. Deane Distinguished Professor of Constitutional Law at Hofstra University School of Law, for their thoughtful comments and feedback on the text of this document. All errors or omissions are the author’s own. ii Freedom of Navigation in the South China Sea: A Practical Guide Table of Contents What is the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS)? ..............1 What are maritime features? ......................................................................1 Why is the distinction between different maritime features important? .................................................................................... 4 What are the territorial sea, the contiguous zone, and the exclusive economic zone? ........................................................... 5 What maritime zones do islands, rocks, and low-tide elevations generate? ....................................................................7 What maritime zones do artificially constructed islands generate? .... -

China Versus Vietnam: an Analysis of the Competing Claims in the South China Sea Raul (Pete) Pedrozo

A CNA Occasional Paper China versus Vietnam: An Analysis of the Competing Claims in the South China Sea Raul (Pete) Pedrozo With a Foreword by CNA Senior Fellow Michael McDevitt August 2014 Unlimited distribution Distribution unlimited. for public release This document contains the best opinion of the authors at the time of issue. It does not necessarily represent the opinion of the sponsor. Cover Photo: South China Sea Claims and Agreements. Source: U.S. Department of Defense’s Annual Report on China to Congress, 2012. Distribution Distribution unlimited. Specific authority contracting number: E13PC00009. Copyright © 2014 CNA This work was created in the performance of Contract Number 2013-9114. Any copyright in this work is subject to the Government's Unlimited Rights license as defined in FAR 52-227.14. The reproduction of this work for commercial purposes is strictly prohibited. Nongovernmental users may copy and distribute this document in any medium, either commercially or noncommercially, provided that this copyright notice is reproduced in all copies. Nongovernmental users may not use technical measures to obstruct or control the reading or further copying of the copies they make or distribute. Nongovernmental users may not accept compensation of any manner in exchange for copies. All other rights reserved. This project was made possible by a generous grant from the Smith Richardson Foundation Approved by: August 2014 Ken E. Gause, Director International Affairs Group Center for Strategic Studies Copyright © 2014 CNA FOREWORD This legal analysis was commissioned as part of a project entitled, “U.S. policy options in the South China Sea.” The objective in asking experienced U.S international lawyers, such as Captain Raul “Pete” Pedrozo, USN, Judge Advocate Corps (ret.),1 the author of this analysis, is to provide U.S. -

Netizens, Nationalism, and the New Media by Jackson S. Woods BA

Online Foreign Policy Discourse in Contemporary China: Netizens, Nationalism, and the New Media by Jackson S. Woods B.A. in Asian Studies and Political Science, May 2008, University of Michigan M.A. in Political Science, May 2013, The George Washington University A Dissertation submitted to The Faculty of The Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of The George Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy January 31, 2017 Bruce J. Dickson Professor of Political Science and International Affairs The Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of The George Washington University certifies that Jackson S. Woods has passed the Final Examination for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy as of September 6, 2016. This is the final and approved form of the dissertation. Online Foreign Policy Discourse in Contemporary China: Netizens, Nationalism, and the New Media Jackson S. Woods Dissertation Research Committee: Bruce J. Dickson, Professor of Political Science and International Affairs, Dissertation Director Henry J. Farrell, Associate Professor of Political Science and International Affairs, Committee Member Charles L. Glaser, Professor of Political Science and International Affairs, Committee Member David L. Shambaugh, Professor of Political Science and International Affairs, Committee Member ii © Copyright 2017 by Jackson S. Woods All rights reserved iii Acknowledgments The author wishes to acknowledge the many individuals and organizations that have made this research possible. At George Washington University, I have been very fortunate to receive guidance from a committee of exceptional scholars and mentors. As committee chair, Bruce Dickson steered me through the multi-year process of designing, funding, researching, and writing a dissertation manuscript. -

Maritime Issues in the East and South China Seas

Maritime Issues in the East and South China Seas Summary of a Conference Held January 12–13, 2016 Volume Editors: Rafiq Dossani, Scott Warren Harold Contributing Authors: Michael S. Chase, Chun-i Chen, Tetsuo Kotani, Cheng-yi Lin, Chunhao Lou, Mira Rapp-Hooper, Yann-huei Song, Joanna Yu Taylor C O R P O R A T I O N For more information on this publication, visit www.rand.org/t/CF358 Published by the RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, Calif. © Copyright 2016 RAND Corporation R® is a registered trademark. Cover image: Detailed look at Eastern China and Taiwan (Anton Balazh/Fotolia). Limited Print and Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law. This representation of intellectual property is provided for noncommercial use only. Unauthorized posting of this publication online is prohibited. Permission is given to duplicate this document for personal use only, as long as it is unaltered and complete. Permission is required to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please visit www.rand.org/pubs/permissions. The RAND Corporation is a research organization that develops solutions to public policy challenges to help make communities throughout the world safer and more secure, healthier and more prosperous. RAND is nonprofit, nonpartisan, and committed to the public interest. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions of its research clients and sponsors. Support RAND Make a tax-deductible charitable contribution at www.rand.org/giving/contribute www.rand.org Preface Disputes over land features and maritime zones in the East China Sea and South China Sea have been growing in prominence over the past decade and could lead to serious conflict among the claimant countries. -

US-China Strategic Competition in South and East China Seas

U.S.-China Strategic Competition in South and East China Seas: Background and Issues for Congress Updated September 8, 2021 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R42784 U.S.-China Strategic Competition in South and East China Seas Summary Over the past several years, the South China Sea (SCS) has emerged as an arena of U.S.-China strategic competition. China’s actions in the SCS—including extensive island-building and base- construction activities at sites that it occupies in the Spratly Islands, as well as actions by its maritime forces to assert China’s claims against competing claims by regional neighbors such as the Philippines and Vietnam—have heightened concerns among U.S. observers that China is gaining effective control of the SCS, an area of strategic, political, and economic importance to the United States and its allies and partners. Actions by China’s maritime forces at the Japan- administered Senkaku Islands in the East China Sea (ECS) are another concern for U.S. observers. Chinese domination of China’s near-seas region—meaning the SCS and ECS, along with the Yellow Sea—could substantially affect U.S. strategic, political, and economic interests in the Indo-Pacific region and elsewhere. Potential general U.S. goals for U.S.-China strategic competition in the SCS and ECS include but are not necessarily limited to the following: fulfilling U.S. security commitments in the Western Pacific, including treaty commitments to Japan and the Philippines; maintaining and enhancing the U.S.-led security architecture in the Western Pacific, including U.S. -

The South China Sea Dispute in 2020-2021

ISSUE: 2020 No. 97 ISSN 2335-6677 RESEARCHERS AT ISEAS – YUSOF ISHAK INSTITUTE ANALYSE CURRENT EVENTS Singapore | 3 September 2020 The South China Sea Dispute in 2020-2021 Ian Storey* EXECUTIVE SUMMARY • Tensions in the South China Sea have surged since the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic. China has pressed its jurisdictional claims prompting the United States to increase its criticism of Beijing’s actions and its military presence in the South China Sea. • In response to China’s activities, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines and Vietnam have rejected Beijing’s nine-dash line claims and invoked international law and the 2016 Arbitral Tribunal ruling in support of their maritime sovereign rights. • As US-China relations spiral downwards, tensions in the South China Sea will intensify. China will double down on its claims and the United States will harden its position no matter which candidate wins the November 2020 US presidential election. • Southeast Asian countries will continue to emphasize international law to protect their rights and interests and try to avoid being drawn into the US-China war of words over the dispute. The ASEAN-China Code of Conduct for the South China Sea will not be signed in 2021. • China is unlikely to terraform Scarborough Shoal into artificial island or establish an Air Defence Identification Zone (ADIZ) over the South China Sea. Vietnam will refrain from legally challenging China’s claims or actions. * Ian Storey is Senior Fellow and co-editor of Contemporary Southeast Asia at the ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute. 1 ISSUE: 2020 No. 97 ISSN 2335-6677 INTRODUCTION Since the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic in March, tensions in the South China Sea have surged. -

Spratly Islands

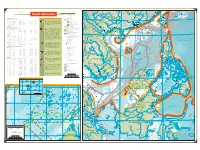

R i 120 110 u T4-Y5 o Ganzhou Fuqing n h Chenzhou g Haitan S T2- J o Dao Daojiang g T3 S i a n Putian a i a n X g i Chi-lung- Chuxiong g n J 21 T6 D Kunming a i Xingyi Chang’an o Licheng Xiuyu Sha Lung shih O J a T n Guilin T O N pa Longyan T7 Keelung n Qinglanshan H Na N Lecheng T8 T1 - S A an A p Quanzhou 22 T'ao-yüan Taipei M an T22 I L Ji S H Zhongshu a * h South China Sea ng Hechi Lo-tung Yonaguni- I MIYAKO-RETTO S K Hsin-chu- m c Yuxi Shaoguan i jima S A T21 a I n shih Suao l ) Zhangzhou Xiamen c e T20 n r g e Liuzhou Babu s a n U T Taichung e a Quemoy p i Meizhou n i Y o J YAEYAMA-RETTO a h J t n J i Taiwan C L Yingcheng K China a a Sui'an ( o i 23 n g u H U h g n g Fuxing T'ai- a s e i n Strait Claimed Straight Baselines Kaiyuan H ia Hua-lien Y - Claims in the Paracel and Spratly Islands Bose J Mai-Liao chung-shih i Q J R i Maritime Lines u i g T9 Y h e n e o s ia o Dongshan CHINA u g B D s Tropic of Cancer J Hon n Qingyuan Tropic of Cancer Established maritime boundary ian J Chaozhou Makung n Declaration of the People’s Republic of China on the Baseline of the Territorial Sea, May 15, 1996 g i Pingnan Heyuan PESCADORES Taiwan a Xicheng an Wuzhou 21 25° 25.8' 00" N 119° 56.3' 00" E 31 21° 27.7' 00" N 112° 21.5' 00" E 41 18° 14.6' 00" N 109° 07.6' 00" E While Bandar Seri Begawan has not articulated claims to reefs in the South g Jieyang Chaozhou 24 T19 N BRUNEI Claim line Kaihua T10- Hsi-yü-p’ing Chia-i 22 24° 58.6' 00" N 119° 28.7' 00" E 32 19° 58.5' 00" N 111° 16.4' 00" E 42 18° 19.3' 00" N 108° 57.1' 00" E China Sea (SCS), since 1985 the Sultanate has claimed a continental shelf Xinjing Guiping Xu Shantou T11 Yü Luxu n Jiang T12 23 24° 09.7' 00" N 118° 14.2' 00" E 33 19° 53.0' 00" N 111° 12.8' 00" E 43 18° 30.2' 00" N 108° 41.3' 00" E X Puning T13 that extends beyond these features to a hypothetical median with Vietnam. -

Indo-Pacific

INDO-PACIFIC Breakthrough in Growing Crops on China’s South China Sea Outposts OE Watch Commentary: Chinese media recently announced a breakthrough in cultivating crops on China’s island and reef outposts in the South China Sea. The new plot for vegetables is on Woody Island, the seat of the Sansha Prefecture that covers all of the South China Sea and the most densely populated of the islands and reefs. Chinese history includes examples of cultivating crops at military outposts for logistical and political reasons as early as the Western Han dynasty (206 BCE – 9 CE). This “Tuntian System” [屯田制] employed farmers, soldiers, and merchants to help settle border areas while providing fresh food to military outposts. These agricultural communities sprung up around the watchtowers of border fortifications protecting China from invasions from the North and settling portions of Xinjiang in the west. In more modern times, the PLA was regarded as a “productive force” and expected to engage in civilian works projects and agriculture. These tasks have been decreased to make room for the demands of training for modern warfare, but it is common to see small garden plots supporting military bases. In the South China Sea, developing fresh sources of vegetables has a more directly significant role. The conditions at these outposts and their distance from the mainland has led to a higher incidence of various illnesses. Some are the result of the harsh environment but others are related to poor diet, which can be addressed through access fresh produce. As noted in the accompanying article, the islands of the Paracels (the archipelago in the northern half of the South China Sea), have long relied entirely on food shipped in from the mainland. -

China, the US, and the Law of the Sea

Current affairs China perspectives China, the US, and the Law of the Sea SÉBASTIEN COLIN he South China Sea, a major transit area of international maritime ever international law allows.” The summit’s joint statement, without clearly traffic, is the scene of territorial and maritime claims expressed by mentioning Chinese initiatives in the South China Sea, included calls for re - the riparian states, including China but also Vietnam, the Philippines, specting “freedom of navigation and overflight” in the maritime areas as well T (10) Malaysia, Brunei, and Taiwan, and now represents one of the main stumbling as “non-militarization and self-restraint in the conduct of activities.” blocks in the US-China bilateral relationship. Between October 2015 and In fact, a major concern in Washington is that this assertion of Chinese mid-May 2016, a series of initiatives taken unilaterally by China on one side presence in the South China Sea will eventually threaten “freedom of nav - and the US on the other have greatly exacerbated the latent confrontation igation” and in the process, American strategic and economic interests. This of the two powers in this maritime space. concern is partly fuelled by China’s official position regarding certain articles Chinese initiatives have essentially consisted of fitting out the Paracel Is - and clauses of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UN - lands and some recently reclaimed reefs of the Spratly archipelago with trans - CLOS) relating to the right of innocent passage through the territorial sea port infrastructure. To this end, the Chinese Ministry of Transport has installed or in the conduct of activities by foreign military ships and aircraft in the three lighthouses on the Spratly Islands: two on Cuarteron and South Johnson exclusive economic zone (EEZ) of the coastal state. -

China's Third Sea Force, the People's Armed Forces Maritime Militia

CHINA MARITIME STUDIES INSTITUTE CENTER FOR NAVAL WARFARE STUDIES U.S. NAVAL WAR COLLEGE 686 CUSHING ROAD (3C) NEWPORT, RHODE ISLAND 02841 China’s Third Sea Force, The People’s Armed Forces Maritime Militia: Tethered to the PLA Conor M. Kennedy and Andrew S. Erickson1 China Maritime Report No. 1 March 2017 China Maritime Studies Institute U.S. Naval War College Newport, Rhode Island Summary Amid growing awareness that China’s Maritime Militia acts as a Third Sea Force which has been involved in international sea incidents, it is necessary for decision-makers who may face such contingencies to understand the Maritime Militia’s role in China’s armed forces. Chinese-language open sources reveal a tremendous amount about Maritime Militia activities, both in coordination with and independent of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA). Using well-documented evidence from the authors’ extensive open source research, this report seeks to clarify the Maritime Militia’s exact identity, organization, and connection to the PLA as a reserve force that plays a parallel and supporting role to the PLA. Despite being a separate component of China’s People’s Armed Forces (PAF), the militia are organized and commanded directly by the PLA’s local military commands. The militia’s status as a separate non-PLA force whose units act as “helpers of the PLA” (解放军的 助手)2 is further reflected in China’s practice of carrying out “joint military, law enforcement, and civilian [Navy-Maritime Law Enforcement-Maritime Militia] defense” (军警民联防). To more accurately capture the identity of the Maritime Militia, the authors propose referring to these irregular forces as the “People’s Armed Forces Maritime Militia” (PAFMM). -

Between Assertiveness and Self-Restraint: Understanding China's South China Sea Policy

Between assertiveness and self-restraint: understanding China’s South China Sea policy ZHOU FANGYIN Since 2010 the situation in the South China Sea, which had been calm during the post-Cold War era, has become more volatile. This has happened in the context of China’s rapid rise and the US ‘pivot’ to Asia. The state of affairs in the South China Sea has been affected by a range of factors, including the transformation of regional power structures, the cognitive adjustments made by the countries involved, and the strategic choices made by powers outside the region in deciding how to deal with the changing regional power structure. Not surprisingly, China’s South China Sea policy has been subject to close international scrutiny; in partic- ular, its assertive behaviour has become a fertile source of controversy and has been much criticized. What are China’s strategic objectives in dealing with the territorial and maritime disputes in the South China Sea? Is China attempting to maximize its power, and to gain as much de facto control over the islands as possible? Is China’s changing South China Sea policy opportunistic behaviour, aimed at establishing regional dominance at a time when it believes there is least likelihood of resistance from the neighbouring countries concerned? Or is China trying to defend its sovereign rights and national interests without jeopardizing stability in the area? This article addresses these questions from an inside-out perspective; that is, it seeks to bring internal Chinese debates and views about China’s strategic goals and policy options to bear on the current debates, and thereby to shed light on hotly debated topics with regard to the controversial Chinese policies towards the South China Sea disputes.