Wiregrass: the Transformation Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Awards Ceremony

South’s BEST 2019 Final Results BEST Award Winners: 1st Place: 966 Starkville High School (Mississippi BEST) 2nd Place: 1351 Ridgecrest Christian Academy (Wiregrass BEST) 3rd Place: 607 Eastwood/Cornerstone Schools (Montgomery BEST) Game Winners: 1st Place Robotics: 966 Starkville High School (Mississippi BEST) 2nd Place Robotics: 873 MACH (Jubilee BEST) 3rd Place Robotics: 803 DARC (Tennessee Valley BEST) 4th Place Robotics (finalist): 1351 Ridgecrest Christian Academy (Wiregrass BEST) Middle School Awards: Top ranking middle school in the BEST Award competition: Woodlawn Beach Middle School (Team 1112 - Emerald Coast BEST) Top ranking middle school in the Robotics competition: Semmes Middle School (Team 881 – Jubilee BEST) The Briggs and Stratton Teacher Leadership Award • Kevin Welch from 1042 Stewarts Creek Middle School (Music City BEST) • Amy Sterling from 1564 Moulton Middle/Lawrence Co. High School (Northwest Alabama BEST) • Beth Lee from 1805 Davis-Emerson Middle School (Shelton State BEST) South’s BEST Volunteer Award • Abigail Madden • Kate Kramer • Beth Rominger (Shelton State BEST) Jim Westmoreland Memorial Judge’s Award • Louis Feirman (Jubilee BEST) 1 BEST Award Category Awards: Best Spirit and Sportsmanship Award: 1st Team: 867 Faith Academy (Jubilee BEST) 2nd Team: 1552 Brooks High School (Northwest Alabama BEST) 3rd Team: 966 Starkville High School (Mississippi BEST) Best Engineering Notebook Award: 1st Team: 851 W.P. Davidson High School (Jubilee BEST) 2nd Team: 1653 Fort Payne High School (Northeast Alabama BEST) 3rd -

Zone 3 – Atlanta Regional Commission

REGIONAL PROFILE ZONE 3 – ATLANTA REGIONAL COMMISSION TABLE OF CONTENTS ZONE POPULATION ........................................................................................................ 2 RACIAL/ETHNIC COMPOSITION ..................................................................................... 2 MEDIAN ANNUAL INCOME ............................................................................................. 3 EDUCATIONAL ACHIEVEMENT ...................................................................................... 4 GEORGIA COMPETITIVENESS INITIATIVE REPORT .................................................... 10 RESOURCES .................................................................................................................. 11 This document is available electronically at: http://www.usg.edu/educational_access/complete_college_georgia/summit ZONE POPULATION 2011 Population 4,069,211 2025 Projected Population 5,807,337 Sources: U.S. Census, American Community Survey 2011 ACS Demographic and Housing Estimates, 5-year estimate Georgia Department of Labor, Area Labor Profile Report 2012 RACIAL/ETHNIC COMPOSITION Source: U.S. Census, American Community Survey 2011 ACS Demographic and Housing Estimates, 5-year estimate 2 MEDIAN ANNUAL INCOME Source: U.S. Census, American Community Survey 2010, Selected Economic Characteristics, 5-year estimate 3 EDUCATIONAL ACHIEVEMENT HIGH SCHOOL GRADUATION RATES SYSTEM NAME 2011 GRADUATION RATE (%) Decatur City 88.40 Buford City 82.32 Fayette 78.23 Cherokee 74.82 Cobb 73.35 Henry -

Of the Wiregrass Primitive Baptists of Georgia: a History of the Crawford Faction of the Alabaha River Primitive Baptist Association, 18422007

The “Gold Standard” of the Wiregrass Primitive Baptists of Georgia: A History of the Crawford Faction of the Alabaha River Primitive Baptist Association, 18422007 A Thesis submitted to the Graduate School Valdosta State University in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in History in the Department of History of the College of the Arts July 2008 Michael Otis Holt BAS, Valdosta State University, 2003 © 2008 Michael Otis Holt All Rights Reserved This thesis, “The ‘Gold Standard’ of the Wiregrass Primitive Baptists of Georgia: A History of the Crawford Faction of the Alabaha River Primitive Baptist Association, 18422007,” by Michael Otis Holt is approved by: Major Professor ___________________________________ John G. Crowley, Ph.D. Associate Professor of History Committee Members ____________________________________ Melanie S. Byrd, Ph.D. Professor of History ____________________________________ John P. Dunn, Ph.D. Assistant Professor of History _____________________________________ Michael J. Stoltzfus, Ph.D. Professor of Philosophy and Religious Studies Dean of Graduate School _____________________________________ Brian U. Adler, Ph.D. Professor of English Fair Use This thesis is protected by the Copyright Laws of the United States (Public Law 94553, revised in 1976). Consistent with fair use as defined in the Copyright Laws, brief quotations from this material are allowed with proper acknowledgement. Use of the material for financial gain without the author’s expressed written permission is not allowed. Duplication I authorize the Head of Interlibrary Loan or the Head of Archives at the Odum Library at Valdosta State University to arrange for duplication of this thesis for educational or scholarly purposes when so requested by a library user. -

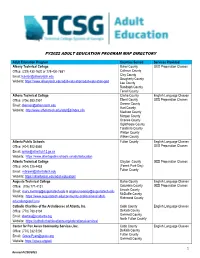

Fy2022 Adult Education Program Map Directory

FY2022 ADULT EDUCATION PROGRAM MAP DIRECTORY Adult Education Program Counties Served Services Provided Albany Technical College Baker County GED Preparation Classes Office: (229) 430-1620 or 229-430-7881 Calhoun County Email: [email protected] Clay County Dougherty County Website: https://www.albanytech.edu/adult-education/adult-education-ged Lee County Randolph County Terrell County Athens Technical College Clarke County English Language Classes Office: (706) 583-2551 Elbert County GED Preparation Classes Email: [email protected] Greene County Hart County Website: http://www.athenstech.edu/adultEd/index.cfm Madison County Morgan County Oconee County Oglethorpe County Taliaferro County Walton County Wilkes County Atlanta Public Schools Fulton County English Language Classes Office: (404) 802-3560 GED Preparation Classes Email: [email protected] Website: https://www.atlantapublicschools.us/adulteducation Atlanta Technical College Clayton County GED Preparation Classes Office: (404) 225-4433 (Forest Park-Day) Email: [email protected] Fulton County Website: https://atlantatech.edu/adult-education/ Augusta Technical College Burke County English Language Classes Office: (706) 771-4131 Columbia County GED Preparation Classes Email: [email protected] & [email protected] Lincoln County McDuffie County Website: https://www.augustatech.edu/community-and-business/adult- Richmond County educationgedell.cms Catholic Charities of the Archdiocese of Atlanta, Inc. Cobb County English Language Classes Office: -

LEAVING CUSTOMARY INTERNATIONAL LAW WHERE IT Is: GOLDSMITH and POSNER's the LIMITS of INTERNATIONAL LAW

LEAVING CUSTOMARY INTERNATIONAL LAW WHERE IT Is: GOLDSMITH AND POSNER'S THE LIMITS OF INTERNATIONAL LAW David M. Golove* TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ......................................... 334 II. THE THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK ............................ 336 A. Self-Interested States? ................................ 337 B. The Supposed Weakness of Customary InternationalLaw ..... 343 Im. EMPIRICAL METHODOLOGY: GOLDSMITH AND POSNER' S APPROACH TO HISTORY ....................................347 IV. CUSTOMARY INTERNATIONAL LAW AND THE CIVIL WAR ........ 350 V. CONCLUSION ........................................... 377 * The Hiller Family Foundation Professor of Law, New York University School of Law. For helpful comments, the author is indebted to Eyal Benvenisti, John Ferejohn, Thomas Franck, Barry Friedman, Clay Gillette, Dan Hulsebosch, Stephen Holmes, Lewis Kornhauser, Mattias Kumm, Daryl Levinson, Susan Lewis, Rick Pildes, and all of the participants in the symposium. This Essay was presented at a symposium on The Limits of InternationalLaw, University of Georgia Law School, October 28-29, 2005. GA. J. INT'L & COMP. L. [Vol. 34:333 I. INTRODUCrION International legal scholarship has long suffered from too much normative theorizing and too little positive analysis about how the international legal system actually works. This inattention to the empirical and descriptive has alienated international legal scholars from their colleagues in political science departments and lent much of international law scholarship an utopian air. Whatever the historical source of this state of affairs, however, it is rapidly fading. A new generation of scholars, steeped in a variety of social scientific methodologies, has turned its sights on international law and is actively employing positive theories of state behavior to enhance legal analyses. These scholars have also begun to undertake empirical studies in an effort to provide support for their theoretical claims. -

GEORGIA ACCREDITING COMMISSION, INC. 2012-2013 Non-Traditional Educational Centers Formerly Accredited By: Accrediting Commission for Independent Study (ACIS)

GEORGIA ACCREDITING COMMISSION, INC. 2012-2013 Non-Traditional Educational Centers Formerly Accredited by: Accrediting Commission for Independent Study (ACIS) The following school programs have been approved by the Commission for the statuses indicated. AWQ - Accredited with Quality ACCF - Accredited Fully ACCA - Accredited Annually Re-visit is the date for the next consultant visit. Please call (912) 632-3783 to ask about a school not listed Grade Status Revisit ABC Montessori School K-12 ACCF 2013 483 Walker Drive McDonough, Ga. 30253 Kimberly Morey, Center Manager 770-957-9998 Alice Blount Academy of Science & Agriculture 6-12 ACCF 2013 582 Mel Blount Road Vidalia, Ga. 30474 Ericka Blount, Center Manager 912-537-7787 The Alleluia Community School K-12 ACCF 2013 2819 Peach Orchard Road P.O. Box 6805 Augusta, Georgia 30906- 6805 Daniel E. Funsch, Center Manager 706-793-9663 Alpha Omega Middle and High School 6-12 AWQ 2013 55 Crowell Road, Ste. M Covington, Ga. 30014 Phillip G. Davenport, Ph. D., Center Manager 770-788-7100 Alternative Youth Academy 6-12 ACCA 2013 2662 Holcomb Bridge Road, Ste. 340 Alpharetta, GA 30022 Llysel Avellano, Center Manager 770-650-0000 Grade Status Revisit Artios Academies-Alpharetta 1-12 ACCA 2013 6910 McGinnis Ferry Road Alpharetta, GA 30005 Michelle Patzer, Center Manager 770-309-7853 Artios Preparatory Academy-Lilburn K-12 ACCF 2013 4805 Highway 78 Lilburn, GA 30047 Lori Lane/Lisa Whitted, Directors 719-966-9258 Asgard Academy 3-12 AWQ 2013 3880 Redbud Court Smyrna, Ga. 30082 Julie Morris, Center Manager 770-881-1701 Barnes Academy,The K-12 ACCF 2013 154 Hart Service Road Hartwell, Georgia 30643 Sarah LeCroy, Center Manager 706-377-3856 BaSix Knowledge Academy K-12 AWQ 2013 2941 Columbia Drive Decatur, Ga. -

John Crews of Camden and His Ancestors

John Crews of Camden and His Ancestors John Crews was born about 1763 in Virginia (1). He is a son of Stanley and Agnes Crews and a grandson to David and Mary Stanley Crews of Virginia (2). He was married to 1st Elizabeth aka Betsey (maiden name unknown); 2nd to Elizabeth Stafford Johns, widow of Jacob Johns. He was one of two of the surname Crews to settle in Camden County, Georgia, during the early-to-mid 1790s. The other Crews family being Isaac Crews, later the Clerk of Court in Camden County, Georgia (no relationship established). These two gentlemen were the first of the Crews surname to settle in Southeast Georgia. John’s grandfather, David Crews (born about 1710-1766) married Mary Stanley (1706- 1766) at the “Friends Meeting House” in Hanover County, Virginia on 9 Nov 1733/34 (2). The children attributed to this union of David and Mary (2) are: David Milton 2 Mar 1740 New Kent County, VA d. 2 Nov,1821 Madison Co., KY Elizabeth born about 1745 Hanover County, VA; m 3 July 1753 (3). John Crews Mary Crews m. Charles Ballew, died about 1811 Stanley - 1740 in VA, died 1792 Wilkes Co., GA m. Agnes (Martin) John's father, Stanley, was the only one of the above-mentioned siblings to settle into Georgia. All others appear to settle in Kentucky. The Stanley Crews family removed from Virginia to Wilkes County, Georgia, after the children were born and he and his brother David’s service in the Continental Army during the American Revolution (2). -

Propaganda Use by the Union and Confederacy in Great Britain During the American Civil War, 1861-1862 Annalise Policicchio

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Duquesne University: Digital Commons Duquesne University Duquesne Scholarship Collection Electronic Theses and Dissertations Summer 2012 Propaganda Use by the Union and Confederacy in Great Britain during the American Civil War, 1861-1862 Annalise Policicchio Follow this and additional works at: https://dsc.duq.edu/etd Recommended Citation Policicchio, A. (2012). Propaganda Use by the Union and Confederacy in Great Britain during the American Civil War, 1861-1862 (Master's thesis, Duquesne University). Retrieved from https://dsc.duq.edu/etd/1053 This Immediate Access is brought to you for free and open access by Duquesne Scholarship Collection. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Duquesne Scholarship Collection. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PROPAGANDA USE BY THE UNION AND CONFEDERACY IN GREAT BRITAIN DURING THE AMERICAN CIVIL WAR, 1861-1862 A Thesis Submitted to the McAnulty College & Graduate School of Liberal Arts Duquesne University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for The Degree of Masters of History By Annalise L. Policicchio August 2012 Copyright by Annalise L. Policicchio 2012 PROPAGANDA USE BY THE UNION AND CONFEDERACY IN GREAT BRITAIN DURING THE AMERICAN CIVIL WAR, 1861-1862 By Annalise L. Policicchio Approved May 2012 ____________________________ ______________________________ Holly Mayer, Ph.D. Perry Blatz, Ph.D. Associate Professor of History Associate Professor of History Thesis Director Thesis Reader ____________________________ ______________________________ James C. Swindal, Ph.D. Holly Mayer, Ph.D. Dean, McAnulty College & Graduate Chair, Department of History School of Liberal Arts iii ABSTRACT PROPAGANDA USE BY THE UNION AND CONFEDERACY IN GREAT BRITAIN DURING THE AMERICAN CIVIL WAR, 1861-1862 By Annalise L. -

IC-25 Subsurface Geology of the Georgia Coastal Plain

IC 25 GEORGIA STATE DIVISION OF CONSERVATION DEPARTMENT OF MINES, MINING AND GEOLOGY GARLAND PEYTON, Director THE GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Information Circular 25 SUBSURFACE GEOLOGY OF THE GEORGIA COASTAL PLAIN by Stephen M. Herrick and Robert C. Vorhis United States Geological Survey ~ ......oi············· a./!.. z.., l:r '~~ ~= . ·>~ a··;·;;·;· .......... Prepared cooperatively by the Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior, Washington, D. C. ATLANTA 1963 CONTENTS Page ABSTRACT .................................................. , . 1 INTRODUCTION . 1 Previous work . • • • • • • . • . • . • . • • . • . • • . • • • • . • . • . • 2 Mapping methods . • . • . • . • . • . • . • . • • . • • . • . • 7 Cooperation, administration, and acknowledgments . • . • . • . • • • • . • • • • . • 8 STRATIGRAPHY. 9 Quaternary and Tertiary Systems . • . • • . • • • . • . • . • . • . • . • • . • . • • . 10 Recent to Miocene Series . • . • • . • • • • • • . • . • • • . • . 10 Tertiary System . • • . • • • . • . • • • . • . • • . • . • . • . • • . 13 Oligocene Series • . • . • . • . • • • . • • . • • . • . • • . • . • • • . 13 Eocene Series • . • • • . • • • • . • . • • . • . • • • . • • • • . • . • . 18 Upper Eocene rocks . • • • . • . • • • . • . • • • . • • • • • . • . • . • 18 Middle Eocene rocks • . • • • . • . • • • • • . • • • • • • • . • • • • . • • . • 25 Lower Eocene rocks . • . • • • • . • • • • • . • • . • . 32 Paleocene Series . • . • . • • . • • • . • • . • • • • . • . • . • • . • • . • . 36 Cretaceous System . • . • . • • . • . • -

Florida Historical Quarterly, Vol. 49, Number 2

Florida Historical Quarterly Volume 49 Number 2 Florida Historical Quarterly, Vol 49, Article 1 Number 2 1970 Florida Historical Quarterly, Vol. 49, Number 2 Florida Historical Society [email protected] Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/fhq University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Full Issue is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Florida Historical Quarterly by an authorized editor of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Recommended Citation Society, Florida Historical (1970) "Florida Historical Quarterly, Vol. 49, Number 2," Florida Historical Quarterly: Vol. 49 : No. 2 , Article 1. Available at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/fhq/vol49/iss2/1 Society: Florida Historical Quarterly, Vol. 49, Number 2 Published by STARS, 1970 1 Florida Historical Quarterly, Vol. 49 [1970], No. 2, Art. 1 FRONT COVER The river front in Jacksonville in 1884. The view is looking west from Liberty Street. The picture is one of several of Jacksonville by Louis Glaser, 1 and it was printed by Witteman Bros. of New York City. The series of 2 /2'' 1 x 4 /2'' views were bound in a small folder for sale to visitors and tourists. This picture is from the P. K. Yonge Library of Florida History, University of Florida. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/fhq/vol49/iss2/1 2 Society: Florida Historical Quarterly, Vol. 49, Number 2 THE FLORIDA HISTORICAL SOCIETY Volume XLIX, Number 2 October 1970 Published by STARS, 1970 3 Florida Historical Quarterly, Vol. 49 [1970], No. -

The Emperor Has No Clothes

THE EMPEROR HAS NO CLOTHES How Hubris, Economics, Bad Timing and Slavery Sank King Cotton Diplomacy with England Joan Thompson Senior Division Individual Paper Thompson 1 All you need in this life is ignorance and confidence, and then the success is sure. -Mark Twain DISASTROUS OVERCONFIDENCE 1 The ancient Greeks viewed hubris as a character flaw that, left unrecognized, caused personal destruction. What is true for a person may be true for a people. For the Confederate States of America, excessive faith in cotton, both its economic and cultural aspects, contributed mightily to its entry into, and ultimate loss of, the Civil War. The eleven states that seceded from the Union viewed British support as both a necessity for Southern success and a certainty, given the Confederacy’s status as the largest (by far) supplier of cotton to Britain. Yet, there was a huge surplus of cotton in Britain when the war began. Moreover, cotton culture’s reliance on slavery presented an insurmountable moral barrier. Southern over-confidence and its strong twin beliefs in the plantation culture and the power of cotton, in the face of countervailing moral values and basic economic laws, blinded the Confederacy to the folly of King Cotton diplomacy. THE CONFLICT: KING COTTON AND SLAVERY Well before the bombardment of Fort Sumter, the South exhibited deep confidence in cotton’s economic power abroad. During the Bloody Kansas debate,2 South Carolina senator James Henry Hammond boasted, “in [the South] lies the great valley of Mississippi…soon to be 1 excessive pride 2 In 1858, Congress debated whether Kansas should be admitted into the Union as a free state or slave state. -

Geological Survey of Alabama

ASSESSMENT OF AQUIFER RECHARGE, GROUND-WATER PRODUCTION IMPACTS, AND FUTURE GROUND-WATER DEVELOPMENT IN SOUTHEAST ALABAMA GEOLOGICAL SURVEY OF ALABAMA Berry H. Tew, Jr. State Geologist ASSESSMENT OF AQUIFER RECHARGE, GROUND-WATER PRODUCTION IMPACTS, AND FUTURE GROUND-WATER DEVELOPMENT IN SOUTHEAST ALABAMA A REPORT TO THE CHOCTAWHATCHEE, PEA, AND YELLOW RIVERS WATERSHED MANAGEMENT AUTHORITY OPEN FILE REPORT 0803 By Marlon R. Cook, Stephen P. Jennings, and Neil E. Moss Submitted in partial fulfillment of a contract with the Choctawhatchee, Pea and Yellow Rivers Watershed Management Authority Tuscaloosa, Alabama 2007 Table of Contents Introduction ........................................................................................................................... 1 Acknowledgments.................................................................................................................. 1 Hydrogeology ........................................................................................................................ 3 Scope of study and methods ............................................................................................ 3 Gordo aquifer................................................................................................................... 8 Ripley/Cusseta aquifer..................................................................................................... 8 Clayton and Salt Mountain aquifers ................................................................................ 9 Nanafalia aquifer.............................................................................................................