Of the Wiregrass Primitive Baptists of Georgia: a History of the Crawford Faction of the Alabaha River Primitive Baptist Association, 18422007

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Awards Ceremony

South’s BEST 2019 Final Results BEST Award Winners: 1st Place: 966 Starkville High School (Mississippi BEST) 2nd Place: 1351 Ridgecrest Christian Academy (Wiregrass BEST) 3rd Place: 607 Eastwood/Cornerstone Schools (Montgomery BEST) Game Winners: 1st Place Robotics: 966 Starkville High School (Mississippi BEST) 2nd Place Robotics: 873 MACH (Jubilee BEST) 3rd Place Robotics: 803 DARC (Tennessee Valley BEST) 4th Place Robotics (finalist): 1351 Ridgecrest Christian Academy (Wiregrass BEST) Middle School Awards: Top ranking middle school in the BEST Award competition: Woodlawn Beach Middle School (Team 1112 - Emerald Coast BEST) Top ranking middle school in the Robotics competition: Semmes Middle School (Team 881 – Jubilee BEST) The Briggs and Stratton Teacher Leadership Award • Kevin Welch from 1042 Stewarts Creek Middle School (Music City BEST) • Amy Sterling from 1564 Moulton Middle/Lawrence Co. High School (Northwest Alabama BEST) • Beth Lee from 1805 Davis-Emerson Middle School (Shelton State BEST) South’s BEST Volunteer Award • Abigail Madden • Kate Kramer • Beth Rominger (Shelton State BEST) Jim Westmoreland Memorial Judge’s Award • Louis Feirman (Jubilee BEST) 1 BEST Award Category Awards: Best Spirit and Sportsmanship Award: 1st Team: 867 Faith Academy (Jubilee BEST) 2nd Team: 1552 Brooks High School (Northwest Alabama BEST) 3rd Team: 966 Starkville High School (Mississippi BEST) Best Engineering Notebook Award: 1st Team: 851 W.P. Davidson High School (Jubilee BEST) 2nd Team: 1653 Fort Payne High School (Northeast Alabama BEST) 3rd -

Introduction and Welcome

Welcome To Grace Primitive Baptist Church We are thankful for your interest in Grace Primitive Baptist Church and pray you will see fit to visit us or visit us again. The purpose of this introductory pamphlet is to better acquaint you with the beliefs of the church. Since we are a typical Primitive Baptist church, much of the pamphlet will discuss the beliefs of Primitive Baptists in general. Primitive Baptists are a small denomination having significant differences from most other churches. These are differences you will want to understand, and we hope you will also examine them under the light of scripture to confirm they are indeed Bible-based. Numerous scriptural references are given for the claims that are made Primitive Baptists are an ancient body. The word “primitive” primarily means “original,” and this is the meaning in “Primitive Baptist.” We have beliefs and practices almost identical to that of Baptists in early America and England. Many Baptists in America derived from the “Regular Baptists.” The Primitive Baptists and old Regular Baptists are essentially the same. One of the most distinguishing marks of Primitive Baptists is that we believe the Bible to be the sole rule of faith and practice. We not only believe the Bible to be inerrant, but also believe it to be sufficient for all spiritual needs and obligations of man (2Tim 3:16, 1Pet 4:11). As a consequence, we aim for a greater degree of Bible conformity than most modern churches. Since the Bible was written in the infinite wisdom of God, we believe it to be void of both error and oversight, and therefore believe any departure from its precepts or precedents will either be in error or else entail loss of effectiveness toward achieving objectives that are important to God. -

Zone 3 – Atlanta Regional Commission

REGIONAL PROFILE ZONE 3 – ATLANTA REGIONAL COMMISSION TABLE OF CONTENTS ZONE POPULATION ........................................................................................................ 2 RACIAL/ETHNIC COMPOSITION ..................................................................................... 2 MEDIAN ANNUAL INCOME ............................................................................................. 3 EDUCATIONAL ACHIEVEMENT ...................................................................................... 4 GEORGIA COMPETITIVENESS INITIATIVE REPORT .................................................... 10 RESOURCES .................................................................................................................. 11 This document is available electronically at: http://www.usg.edu/educational_access/complete_college_georgia/summit ZONE POPULATION 2011 Population 4,069,211 2025 Projected Population 5,807,337 Sources: U.S. Census, American Community Survey 2011 ACS Demographic and Housing Estimates, 5-year estimate Georgia Department of Labor, Area Labor Profile Report 2012 RACIAL/ETHNIC COMPOSITION Source: U.S. Census, American Community Survey 2011 ACS Demographic and Housing Estimates, 5-year estimate 2 MEDIAN ANNUAL INCOME Source: U.S. Census, American Community Survey 2010, Selected Economic Characteristics, 5-year estimate 3 EDUCATIONAL ACHIEVEMENT HIGH SCHOOL GRADUATION RATES SYSTEM NAME 2011 GRADUATION RATE (%) Decatur City 88.40 Buford City 82.32 Fayette 78.23 Cherokee 74.82 Cobb 73.35 Henry -

Georgia Black Bear Project Report & Status Update (US Fish & Wildlife

GEORGIA BLACK BEAR PROJECT REPORT AND STATUS UPDATE BOBBY BOND, Georgia Department of Natural Resources, Wildlife Resources Division, 1014 Martin Luther King Boulevard, Fort Valley, GA 31030 ADAM HAMMOND, Georgia Department of Natural Resources, Wildlife Resources Division, 2592 Floyd Springs Road, Armuchee, GA 30105 GREG NELMS, Georgia Department of Natural Resources, Wildlife Resources Division, 108 Darling Avenue, Waycross, GA 31501 Abstract: Throughout Georgia, bear populations are stable to increasing in size. Bait station surveys were conducted to determine distribution and population trends of bears in north, central, and south Georgia during July of 2008. Results of these surveys, expressed as percent bait station hits, were 71.04%, 45%, and 35.8% for stations in north, central, and south Georgia respectively. Concurrently, harvest in the north, central, and south Georgia populations was 314, 0, and 57 bears, respectively. The black bear (Ursus americanus) symbolizes the wild qualities of Georgia. Prior to the eighteenth century bears were common in Georgia. However, habitat loss, unrestricted hunting and overall degradation of habitat because of human development contributed to a Fig. 1 – Black Bear Distribution serious population decline. Georgia Department of Natural and Range in Georgia. Resources wildlife management practices, improvements in law enforcement, and social changes all have contributed to the recovery of bear populations. In Georgia, we have 3 more/less distinct bear populations: 1) north Georgia associated with the Southern Appalachians 2) central Georgia along the Ocmulgee River drainage 3) southeast Georgia in/around the Okefenokee Swamp (U. a. floridanus) (Fig. 1). All three populations are believed to be either stable or slightly increasing. -

Coffee History

Camp Meetings Georgia is a camp meeting state and all the history of camp :b meetings h a s not been written. They come and go. Dooly County and Liberty County have camp meetings in opera- tion and there may be others as far as I know. Also Tatnall County. The Gaslcin REV. GREEN TAYLOR Springs camp meet- A distinguished camp meeting preacher ing was started about before the war. 1895. Gaslrin Springs is situated about two miles east of Douglas on the east side of the Seventeen-Mile Creek. Mr. Joel Gaskin donat,ed four acres of land to certain trustees named in the deed with the expressed provision that the said land was to be used as camp meeting purposes. The lands to revert to the donor when it ceased to be used for camp meeting purposes. This deed carried with it the right to use the water from Gaskin Springs for the camp meetings. A large pavillion was built near the spring. 'llhe pavillioii would seat several hundred people. A bridge was built across the Seventeen-Mile Creek for pec1estria.n~ between Douglas and the Springs. Many families from Douglas, Broxton, and people from surrounding counties built houses, where their families moved and kept open house during the camp meeting times for ten days once a year. The camp meeting was under the supervision of the Methodist Church. The pre- siding elder of the Douglas church had charge of the camp grounds and selected the preachers. However, ministers of all denominations were invited to preach. Several services would be held each day. -

Region 1 Region 7

Georgia Association of REALTORS® REGION 1 REGION 7 . Carpet Capital Association of REALTORS® . Albany Board of REALTORS® . Cherokee Association of REALTORS® Inc . Americus Board of REALTORS® . Cobb Association of REALTORS® . Crisp Area Board of REALTORS® Inc . Northwest Metro Association of REALTORS® . Moultrie Board of REALTORS® . NW GA Council (Chattanooga Association of . Southwest Georgia Board of REALTORS® Inc REALTORS® Inc) . Thomasville Area Board of REALTORS® . Pickens County Board of REALTORS® Inc REGION 8 REGION 2 . Camden Charlton County Board of REALTORS® . 400 North Board of REALTORS® . Douglas Coffee County Board of REALTORS® Inc . Georgia Mountain & Lakes REALTORS® . Golden Isles Association of REALTORS®, Inc . Hall County Board of REALTORS® . Southeast Council of the Georgia REALTORS® . Northeast Atlanta Metro Association of . Tiftarea Board of REALTORS® Inc REALTORS® Inc . Valdosta Board of REALTORS® . Northeast Georgia Board of REALTORS® Inc REGION 9 REGION 3 . Altamaha Basin Board of REALTORS® Inc ® ® . Atlanta REALTORS Association . Dublin Board of REALTORS ® ® . Atlanta Commercial Board of REALTORS . Hinesville Area Board of REALTORS Inc ® ® . Greater Rome Board of REALTORS Inc . The REALTORS Commercial Alliance ® . Paulding Board of REALTORS Inc Savannah/Hilton Head Inc ® ® . West Georgia Board of REALTORS . Savannah Area REALTORS ® ® . West Metro Board of REALTORS Inc . Statesboro Board of REALTORS Inc REGION 4 ® . DeKalb Association of REALTORS Inc ® . East Metro Board of REALTORS Inc . ® Fayette County Board of REALTORS Inc . Heart of Georgia Board of REALTORS® . Metro South Association of REALTORS® Inc . Newnan Coweta Board of REALTORS® Inc REGION 5 . Athens Area Association of REALTORS® Inc . Greater Augusta Association of REALTORS® Inc . Georgia Upstate Lakes Board of REALTORS® Inc . I-85 North Board of REALTORS® Inc . -

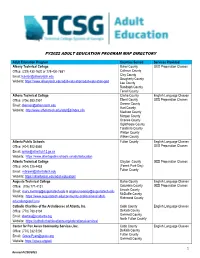

Fy2022 Adult Education Program Map Directory

FY2022 ADULT EDUCATION PROGRAM MAP DIRECTORY Adult Education Program Counties Served Services Provided Albany Technical College Baker County GED Preparation Classes Office: (229) 430-1620 or 229-430-7881 Calhoun County Email: [email protected] Clay County Dougherty County Website: https://www.albanytech.edu/adult-education/adult-education-ged Lee County Randolph County Terrell County Athens Technical College Clarke County English Language Classes Office: (706) 583-2551 Elbert County GED Preparation Classes Email: [email protected] Greene County Hart County Website: http://www.athenstech.edu/adultEd/index.cfm Madison County Morgan County Oconee County Oglethorpe County Taliaferro County Walton County Wilkes County Atlanta Public Schools Fulton County English Language Classes Office: (404) 802-3560 GED Preparation Classes Email: [email protected] Website: https://www.atlantapublicschools.us/adulteducation Atlanta Technical College Clayton County GED Preparation Classes Office: (404) 225-4433 (Forest Park-Day) Email: [email protected] Fulton County Website: https://atlantatech.edu/adult-education/ Augusta Technical College Burke County English Language Classes Office: (706) 771-4131 Columbia County GED Preparation Classes Email: [email protected] & [email protected] Lincoln County McDuffie County Website: https://www.augustatech.edu/community-and-business/adult- Richmond County educationgedell.cms Catholic Charities of the Archdiocese of Atlanta, Inc. Cobb County English Language Classes Office: -

Georgia Nursing August, September, October 2011 2010 Earnings and Employment Continued from Page 1 GEORGIA NURSING

“Nurses shaping the future of professional nursing and advocating for quality health care.” The official publication of the Georgia Nurses Association (GNA) Brought to you by the Georgia Nurses Association (GNA), whose dues-paying members make it possible to advocate for nurses and nursing at the state and federal level. Volume 71 • No. 3 August, September, October 2011 Quarterly circulation approximately 105,000 to all RNs and Student Nurses in Georgia. 2010 Earnings and Employment of RNs PRESIDENT ’S MESSAGE U.S. Bureau of Labor Releases Employment Data Extracted from ANA policy brief prepared by was California, which also exhibited the highest A Better Way Peter McMenamin, PhD, Senior Policy Fellow in average annual wage, $87,480. The average wage the Department of Nursing Practice and Policy, in Iowa was $51,970, the lowest average wage state. By Fran Beall, RN, ANP, BC American Nurses Association Wyoming had the fewest number of RN jobs at 4,790. The RN data from BLS Occupational Employment I’ve had several oppor In 2010, there were an estimated 2,655,020 Statistics (OES) differs from the National Sample Survey tunities recently to think registered nurses working in RN jobs. That is of Registered Nurses (NSSRN – http://datawarehouse. about conflict and change an increase of three percent (71,250 more jobs). hrsa.gov/nursingsurvey.aspx conducted by the Health in the workplace, and why The Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) reports the Resources and Services Administration (HRSA). In some nurses either do or don’t estimated average wage for RNs in 2010 was $67,720. -

Coastal Plain of Georgia

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY GEORGE OTIS SMITH, DIBECTOK WATER-SUPPLY PAPER UNDERGROUND WATERS OF THE COASTAL PLAIN OF GEORGIA BY L. W. STEPHENSON AND J. 0. VEATCH AND A DISCUSSION OP THE QUALITY OF THE WATERS BY R. B. DOLE Prepared in cooperation with the Geological Survey of Georgia WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 1915 CONTENTS. __ Page. Introduction.............................................................. 25 Physiography.............................................................. 26 Cumberland Plateau.................................................... 26 Appalachian Valley.................................................... 27 Appalachian Mountains................................................ 27 Piedmont Plateau..................................................... 27 Coastal Plain........................................................... 28 General features................................................... 28 Physiographic subdivisions......................................... 29 Fall-line Mils................................................. 29 Dougherty plain............................................... 31 Altamaha upland............................................... 32 Southern limesink region...................................... 34 Okefenokee plain.............................................. 35 Satilla coastal lowland ......................................... 36 Minor features..................................................... 38 Terraces...................................................... -

The Kehukee Declaration Halifax County

The Kehukee Declaration Halifax County, North Carolina 1827 THE KEHUKEE DECLARATION A DECLARATION AGAINST THE MODERN MISSIONARY MOVEMENT AND OTHER INSTITUTIONS OF MEN In a resolution adopted by the Kehukee Association, while convened with the Kehukee Church, Halifax County, N. C. Saturday before the first Sunday in October, 1827. 1826 Session of the Kehukee Association convened on Saturday before the first Sunday in October, 1826, at Skewarky, Martin County, N. C. Matters were now becoming so unsatisfactory to many of the churches and brethren in regard to missionary operations, Masonic Lodges, Secret Societies generally, etc., etc., that it seemed necessary to take a decided stand against them, and thereby no longer tolerate these innovations on the ancient usages of the church of Christ by fellowshipping them. Accordingly, we notice in the proceedings of the session held at this time the following item: “A paper purporting to be a Declaration of the Reformed Baptist Churches of North Carolina (read on Saturday and laid on the table this day, Monday), was called up for discussion and was referred to the churches, to report, in their letters to the next Association, their views on each article therein contained.” 1827. The Association met at Kehukee, Halifax County on Saturday before the first Sunday in October, 1827. 1827. This session of the Association was one of the most remarkable ever held by her. At this time came up for consideration the Declaration of Principles submitted at the last session to the churches for approval or rejection. And upon a full and fair discussion of them, the following order was made, viz.: “A paper purporting to be a Declaration of the Reformed Baptists in North Carolina, dated August 26, 1826, which was presented at last Association, and referred to the churches to express in their letters to this Association their views with regard to it, came up for deliberation. -

The History of the Baptists of Tennessee

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 6-1941 The History of the Baptists of Tennessee Lawrence Edwards University of Tennessee - Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Edwards, Lawrence, "The History of the Baptists of Tennessee. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 1941. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/2980 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Lawrence Edwards entitled "The History of the Baptists of Tennessee." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Master of Arts, with a major in History. Stanley Folmsbee, Major Professor We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance: J. B. Sanders, J. Healey Hoffmann Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) August 2, 1940 To the Committee on Graduat e Study : I am submitting to you a thesis wr itten by Lawrenc e Edwards entitled "The History of the Bapt ists of Tenne ssee with Partioular Attent ion to the Primitive Bapt ists of East Tenne ssee." I recommend that it be accepted for nine qu arter hours credit in partial fulfillment of the require ments for the degree of Ka ster of Art s, with a major in Hi story. -

Magnitude and Frequency of Rural Floods in the Southeastern United States, 2006: Volume 1, Georgia

Prepared in cooperation with the Georgia Department of Transportation Preconstruction Division Office of Bridge Design Magnitude and Frequency of Rural Floods in the Southeastern United States, 2006: Volume 1, Georgia Scientific Investigations Report 2009–5043 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Cover: Flint River at North Bridge Road near Lovejoy, Georgia, July 11, 2005. Photograph by Arthur C. Day, U.S. Geological Survey. Magnitude and Frequency of Rural Floods in the Southeastern United States, 2006: Volume 1, Georgia By Anthony J. Gotvald, Toby D. Feaster, and J. Curtis Weaver Prepared in cooperation with the Georgia Department of Transportation Preconstruction Division Office of Bridge Design Scientific Investigations Report 2009–5043 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior KEN SALAZAR, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Suzette M. Kimball, Acting Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2009 For more information on the USGS--the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment, visit http://www.usgs.gov or call 1-888-ASK-USGS For an overview of USGS information products, including maps, imagery, and publications, visit http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod To order USGS information products, visit http://store.usgs.gov Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this report is in the public domain, permission must be secured from the individual copyright owners to reproduce any copyrighted materials contained within this report.