Young Leaders

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Electoral Politics in South Korea

South Korea: Aurel Croissant Electoral Politics in South Korea Aurel Croissant Introduction In December 1997, South Korean democracy faced the fifteenth presidential elections since the Republic of Korea became independent in August 1948. For the first time in almost 50 years, elections led to a take-over of power by the opposition. Simultaneously, the election marked the tenth anniversary of Korean democracy, which successfully passed its first ‘turnover test’ (Huntington, 1991) when elected President Kim Dae-jung was inaugurated on 25 February 1998. For South Korea, which had had six constitutions in only five decades and in which no president had left office peacefully before democratization took place in 1987, the last 15 years have marked a period of unprecedented democratic continuity and political stability. Because of this, some observers already call South Korea ‘the most powerful democracy in East Asia after Japan’ (Diamond and Shin, 2000: 1). The victory of the opposition over the party in power and, above all, the turnover of the presidency in 1998 seem to indicate that Korean democracy is on the road to full consolidation (Diamond and Shin, 2000: 3). This chapter will focus on the role elections and the electoral system have played in the political development of South Korea since independence, and especially after democratization in 1987-88. Five questions structure the analysis: 1. How has the electoral system developed in South Korea since independence in 1948? 2. What functions have elections and electoral systems had in South Korea during the last five decades? 3. What have been the patterns of electoral politics and electoral reform in South Korea? 4. -

Elections During Crisis: Global Lessons from the Asia-Pacific

Governing During Crises Policy Brief No. 10 Elections During Crisis Global Lessons from the Asia-Pacific 17 March 2021 | Tom Gerald Daly Produced in collaboration with Election Watch and Policy Brief | Election Lessons from the Asia-Pacific Page 1 of 13 Summary _ Key Points This Policy Brief makes the following key points: (a) During 2020 states the world over learned just how challenging it can be to organise full, free, and fair elections in the middle of a pandemic. For many states facing important elections during 2021 (e.g. Japan, the UK, Israel) these challenges remain a pressing concern. (b) The pandemic has spurred electoral innovations and reform worldwide. While reforms in some states garner global attention – such as attempts at wholesale reforms in the US (e.g. early voting) – greater attention should be paid to the Asia-Pacific as a region. (c) A range of positive lessons can be drawn from the conduct of elections in South Korea, New Zealand, Mongolia, and Australia concerning safety measures, effective communication, use of digital technology, advance voting, and postal voting. Innovations across the Asia-Pacific region provide lessons for the world, not only on effectively running elections during a public health emergency, but also pointing to the future of election campaigns, in which early and remote voting becomes more common and online campaigning becomes more central. (d) Experiences elsewhere raise issues to watch out for in forthcoming elections in states and territories undergoing serious ‘pandemic backsliding’ in the protection of political freedoms. Analysis of Singapore and Indonesia indicates a rise in censorship under the pretext of addressing misinformation concerning COVID-19, and (in Indonesia) concerns about ‘vote- buying’ through crisis relief funds. -

The Political Business Cycle in Asian Countries

Journal of Business and Economics, ISSN 2155-7950, USA October 2019, Volume 10, No. 10, pp. 966-980 DOI: 10.15341/jbe(2155-7950)/10.10.2019/005 Academic Star Publishing Company, 2019 http://www.academicstar.us The Political Business Cycle in Asian Countries Ling-Chun Hung (Department of Political Science, National Cheng Kung University, Taiwan (R.O.C.)) Abstract: The political business cycle (PBC) theory argues that an incumbent party tends to use government resources to impress voters, so government spending always rises before but declines after an election. Many PBC studies have been done for an individual country or cross-countries, but the results are conflicting. The purpose of this paper is to explore possible fluctuating patterns of government spending in response to political elections in Asian countries because of a lack of studies across this region. In this study, data on 219 elections in 26 countries from 1990 to 2014 are collected. There are two main findings: firstly, government spending falls the year after elections in Asian countries; secondly, the degree of democracy and transparency have impacts on government spending in Asian countries. Key words: political business cycle; election cycle; government spending; government expenditure; Asian JEL code: H51 1. Introduction The political business cycle (PBC) theory has been addressed for four decades. The theory states that an incumbent party will use government resources to impress voters, so economic performance is good before but is poor after an election. However, empirically, scholars have not reach a consensus. Many PBC studies have been done for an individual country or cross-countries, but the results have not been consistent. -

Domestic Constraints on South Korean Foreign Policy

Domestic Constraints on South Korean Foreign Policy January 2018 Domestic Constraints on South Korean Foreign Policy Scott A. Snyder, Geun Lee, Young Ho Kim, and Jiyoon Kim The Council on Foreign Relations (CFR) is an independent, nonpartisan membership organization, think tank, and publisher dedicated to being a resource for its members, government officials, business execu- tives, journalists, educators and students, civic and religious leaders, and other interested citizens in order to help them better understand the world and the foreign policy choices facing the United States and other countries. Founded in 1921, CFR carries out its mission by maintaining a diverse membership, with special programs to promote interest and develop expertise in the next generation of foreign policy leaders; con- vening meetings at its headquarters in New York and in Washington, DC, and other cities where senior government officials, members of Congress, global leaders, and prominent thinkers come together with CFR members to discuss and debate major international issues; supporting a Studies Program that fosters independent research, enabling CFR scholars to produce articles, reports, and books and hold roundtables that analyze foreign policy issues and make concrete policy recommendations; publishing Foreign Affairs, the preeminent journal on international affairs and U.S. foreign policy; sponsoring Independent Task Forces that produce reports with both findings and policy prescriptions on the most important foreign policy topics; and providing up-to-date information and analysis about world events and American foreign policy on its website, CFR.org. The Council on Foreign Relations takes no institutional positions on policy issues and has no affilia- tion with the U.S. -

Democracy in the Age of Pandemic – Fair Vote UK Report June 2020

Democracy in the Age of Pandemic How to Safeguard Elections & Ensure Government Continuity APPENDICES fairvote.uk Published June 2020 Appendix 1 - 86 1 Written Evidence, Responses to Online Questionnaire During the preparation of this report, Fair Vote UK conducted a call for written evidence through an online questionnaire. The questionnaire was open to all members of the public. This document contains the unedited responses from that survey. The names and organisations for each entry have been included in the interest of transparency. The text of the questionnaire is found below. It indicates which question each response corresponds to. Name Organisation (if applicable) Question 1: What weaknesses in democratic processes has Covid-19 highlighted? Question 2: Are you aware of any good articles/publications/studies on this subject? Or of any countries/regions that have put in place mediating practices that insulate it from the social distancing effects of Covid-19? Question 3: Do you have any ideas on how to address democratic shortcomings exposed by the impact of Covid-19? Appendix 1 - 86 2 Appendix 1 Name S. Holledge Organisation Question 1 Techno-phobia? Question 2 Estonia's e-society Question 3 Use technology and don't be frightened by it 2 Appendix 1 - 86 3 Appendix 2 Name S. Page Organisation Yes for EU (Scotland) Question 1 The Westminster Parliament is not fit for purpose Question 2 Scottish Parliament Question 3 Use the internet and electronic voting 3 Appendix 1 - 86 4 Appendix 3 Name J. Sanders Organisation emergency legislation without scrutiny removing civil liberties railroading powers through for example changes to mental health act that impact on individual rights (A) Question 1 I live in Wales, and commend Mark Drakeford for his quick response to the crisis by enabling the Assembly to continue to meet and debate online Question 2 no, not until you asked. -

South Korea | Freedom House: Freedom in the World 2019

South Korea | Freedom House https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-world/2019/south-korea A. ELECTORAL PROCESS: 11 / 12 A1. Was the current head of government or other chief national authority elected through free and fair elections? 4 / 4 The 1988 constitution vests executive power in a directly elected president, who is limited to a single five-year term. Executive elections in South Korea are largely free and fair. Moon Jae-in of the liberal Minjoo Party won a May 2017 snap presidential election following the impeachment of former president Park. He took 41 percent of the vote, followed by Hong Jun-pyo of the conservative Liberty Korea Party with 24 percent and Ahn Cheol-soo of the centrist People’s Party with 21 percent. About 77 percent of registered voters turned out for the election. In the June 2018 local elections, the Minjoo Party won 14 of 17 metropolitan mayoral and gubernatorial offices, with two of the others going to the Liberty Korea Party and one to an independent. Turnout for the local elections was 60.2 percent, marking the first time the voting rate had surpassed 60 percent for local elections since 1995. A2. Were the current national legislative representatives elected through free and fair elections? 4 / 4 The unicameral National Assembly is composed of 300 members serving four-year terms, with 253 elected in single-member constituencies and 47 through national party lists. The contests are typically free of major irregularities. In the 2016 elections, the Minjoo Party won 123 seats, while the Saenuri Party (which later became the Liberty Korea Party) won 122. -

Internet Appendix to “Political Uncertainty and Corporate Investment Cycles"*

Internet Appendix to “Political Uncertainty and Corporate Investment Cycles"* *Citation format: Julio, Brandon, and Youngsuk Yook, Internet Appendix to “Political Uncertainty and Corporate Investment Cycles,” Journal of Finance, DOI: 10.1111/j.1540-6261.2011.01707.x. Please note: Wiley-Blackwell is not responsible for the content or functionality of any supporting information supplied bythe authors. Any queries (other than missing material) should be directed to the authors of the article. Table AI Alternative Proxies for Investment Opportunities This table reports the estimates of the baseline investment regression specification. Each column reports the estimates of the regression using different proxies for firm investment opportunities. The first column uses the same proxy for Tobin’s Q as in Table III, defined as the book value of total assets minus the book value of total equity plus the market value of equity scaled by the book value of total assets. The second column reports the results using the worldwide industry-year average of Tobin’s Q for each three-digit SIC industry. The third column uses the median industry-level Tobin’s Q each year as the proxy for growth opportunities, based on three- digit SIC industries. The final column employs sales growth, defined as the percentage change in sales over the previous year for each firm. Standard errors, clustered by country and year, are reported in brackets. (1) (2) (3) (4) ElectionYearDummy -0.0039 -0.0040 -0.0040 -0.0039 [0.0013]*** [0.0015]** [0.0015]** [0.0013]*** Q 0.0055 [0.0010]*** -

Early Observer Missions

THE EVOLUTION OF PEACEKEEPING: EARLY UN OBSERVER MISSIONS (1946-56) Dr. Walter Dorn 13 April 2011 EARLY MISSIONS: OVERVIEW Greek Border - Commission of Investigation: 1946 - Special Committee on the Balkans (UNSCOB): 1947 Indonesia - Consular Commission: 1947 - Good Offices Commission: 1947 - Commission for Indonesia: 1949 Korea - Temporary Commission on Korea (UNTCOK): 1947 - Commission on Korea (UNCOK): 1948 EARLY MISSIONS (CONT’D) Palestine - Special Committee on Palestine (UNSCOP): 1947 - Commission on Palestine (UNCP): 1947 - Truce Commission: 1948 - Truce Supervision Organization (UNTSO): 1948 - Palestine Conciliation Commission (PCC): 1948 Kashmir - Commission in India and Pakistan (UNCIP): 1948 - Military Observer Group in India and Pakistan (UNMOGIP): 1948 - UN Representative: 1950 CASE: KOREA • Historically, caught between Larger Powers – Chinese tributary – Sino-Japanese War (1894-95) • Fight over Korea • Japanese “trusteeship” – Russo-Japanese War (1904-5) • Russians accept Japanese dominance in Korea – Japanese annexation/colonization (1910-45) • US/USSR accept Japanese surrender after WW II – Beginning of Korean division “Whales fight, shrimp crushed." – Korean sokdam (proverb) POST-WW II SITUATION • Temporary zones: – Soviet zone (North of 38th parallel) and – American zone (South) • Superpowers can’t agree on means of reunification • Issue passed to UN by US www.awm.gov.au UN CHRONOLOGY 1947 Nov 14 GA establishes UN Temporary Commission on Korea (UNTCOK) to facilitate a National Government, election observation and the withdrawal of Soviet & American forces 1948 May 10 UNTCOK observes elections in South Korea only (refused in North) as “expression of free will.” GA approves July Establishment of Republic of Korea (ROK) (claiming all of Korea) with Syngman Rhee as President ELECTIONS 1948 (S. KOREA) AWM P0716/113/003 Chongiu. -

Views from Asia“Ł

VIEWS FROM ASIA Considering the Politics of East Asia: South Korea and Taiwan By Shiraishi Takashi HIS past March, a presidential who support the Roh administration “3” referring to the fact that they turned T election was held in Taiwan, and gained a stable majority. As a result, it 30 in the 1990s, “8” to their attending the incumbent president, Chen Shui- is becoming a real issue whether the university in the 1980s and “6” to their bian, and vice-president, Annette Lu of National Security Law will be changed birth in the 1960s. This generation has the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) in the National Assembly. This law not experienced Japanese control as a narrowly defeated Lien Chan, chairman was passed in August 1948, three colony or the Korean War of 1950-53. of the opposition Kuomintang Party months after South Korea was estab- What they have experienced is economic (KMT), and James Soong, chairman of lished, and it treats North Korea as an development under the authoritarian the People First Party (PFP), as a presi- “anti-State group,” establishing severe leader Park Chung-hee and the student dential and vice-presidential candidate punishments – including the death movement opposing oppressive political respectively. The difference in the votes penalty – for those who break the law. rule in the 1980s. As a consequence, received was just over 29,000, with the It is this law which has been used as a they take peace and prosperity as a nat- winner gaining a minuscule 0.22% vic- tool by successive military administra- ural course of events; maintain doubts tory. -

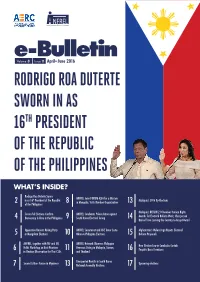

ANFREL E-Bulletin Volume #3, Issue #2

e-Bulletin Volume 3 Issue 2 April–June 2016 RODRIGO ROA DUTERTE SWORN IN AS 16TH PRESIDENT OF THE REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES WHAT’S INSIDE? Rodrigo Roa Duterte Sworn ANFREL Joins FORUM-ASIA for a Mission in as 16th President of the Republic Malaysia’s 2016 By-Elections 2 8 in Mongolia, Visits Member Organization 13 of the Philippines Malaysia’s BERSIH 2.0 Receives Human Rights Successful Elections Conrm ANFREL Condemns Police Action against Awards for Electoral Reform Work; Chairperson 4 Democracy Is Alive in the Philippines 9 South Korea Electoral Group 14 Barred from Leaving the Country to Accept Award Opposition Unseats Ruling Party ANFREL Secretariat and CNE Timor Leste Afghanistan’s Wolesi Jirga Rejects Electoral 5 in Mongolian Elections 10 Observe Philippine Elections 15 Reform Proposals ANFREL, together with TAF and IRI, ANFREL Network Observes Philippine New Election Law in Cambodia Curtails Holds Workshop on Best Practices Overseas Voting in Malaysia, Taiwan, 6 11 16 People’s Basic Freedoms in Election Observation for Thai CSOs and Thailand Unexpected Results in South Korea Second Editors Forum in Myanmar Upcoming elections 7 13 National Assembly Elections 17 2 HIGHLIGHT ANFREL congratulates the Philippines on its summary executions of individuals suspected successful holding of the May 9, 2016 national of petty crimes and dealing in drugs in Davao. and local elections. But Duterte’s straightforward, sometimes On 30 June 2016, the new set of leaders ofcially out-of-control, manner of speaking endeared assumed their posts. President Benigno Simeon him to Filipino voters. As a candidate, he Aquino III handed over the presidency to promised the voters that he would bring real President Rodrigo Duterte in a ceremony held change. -

Regionalism in South Korean National Assembly Elections

Regionalism in South Korean National Assembly Elections: A Vote Components Analysis of Electoral Change* Eric C. Browne and Sunwoong Kim Department of Political Science Department of Economics University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee University of Wisconsin- Milwaukee [email protected] [email protected] July 2003 * This paper was originally presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association, San Francisco, 29 August – 2 September, 2001. We acknowledge useful comments and suggestions by the session participants, Ronald Weber and anonymous referees. Abstract We analyze emerging regionalism in South Korean electoral politics by developing a “Vote Components Analysis” and applying this technique to data from the eleven South Korean National Assembly elections held between 1963 and 2000. This methodology allows us to decompose the change in voting support for a party into separate effects that include measurement of an idiosyncratic regional component. The analysis documents a pronounced and deepening regionalism in South Korean politics since 1988 when democratic reforms of the electoral system were fully implemented. However, our results also indicate that regional voters are quite responsive to changes in the coalitions formed by their political leaders but not to the apparent mistreatment of, or lack of resource allocations to, specific regions. Further, regionalism does not appear to stem from age-old rivalries between the regions but rather from the confidence of regional voters in the ability of their “favorite sons” to protect their interests and benefit their regions. JEL Classification: N9, R5 Keywords: Regionalism, South Korea, Elections, Vote Components Analysis 2 1. INTRODUCTION The history of a very large number of modern nation-states documents a cyclical pattern of territorial incorporation and disincorporation in their political development. -

South Korean Politics in Transition: Democratization, Elections, and The

IRlBGllMlB CIEIANGlB AND IRlBGllMlB MAllN'lI'lBNANClB llN ASllA AND 'fIEilB lPAClllFllC Discussion Paper No. 20 South Korean Politics in Transition: Democratization, Elections, and the Voters SUN KWANG-BAE Published by The Department of Political and Social Change Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies The Australian National University 1997 REGIME CHANGE AND REGIME MAINTENANCE IN ASIA AND THE PACIFIC In recent years there have been some dramaticchanges of political leadership in the Asia-Pacificregion, and also some dramas without leadership change. In a few countries the demise of well-entrenched political leaders appears immi nent; in others regular processes of parliamentary government still prevail. These differing patterns of regime change and regime maintenance raise fundamental questions about the nature of political systems in the region. Specifically,how have some political leaders or leadership groups been able to stay in power for relatively long periods and why have they eventually been displaced? What are the factors associated with the stability or instability of political regimes? What happens when longstanding leaderships change? The Regime Change and Regime Maintenance in Asia and the Pacific Project will address these and other questions from an Asia-Pacific regional perspective and at a broader theoretical level. The project is under the joint direction of Dr R.J. May and Dr Harold Crouch. For further information about the project write to: The Secretary Department of Political and Social Change Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies (RSP AS) The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200 Australia © Department of Political and Social Change, Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies, The AustralianNational University, 1997.