Contextual Determinants of Electoral System Choice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Case for Electoral Reform: a Mixed Member Proportional System

1 The Case for Electoral Reform: A Mixed Member Proportional System for Canada Brief by Stephen Phillips, Ph.D. Instructor, Department of Political Science, Langara College Vancouver, BC 6 October 2016 2 Summary: In this brief, I urge Parliament to replace our current Single-Member Plurality (SMP) system chiefly because of its tendency to distort the voting intentions of citizens in federal elections and, in particular, to magnify regional differences in the country. I recommend that SMP be replaced by a system of proportional representation, preferably a Mixed Member Proportional system (MMP) similar to that used in New Zealand and the Federal Republic of Germany. I contend that Parliament has the constitutional authority to enact an MMP system under Section 44 of the Constitution Act 1982; as such, it does not require the formal approval of the provinces. Finally, I argue that a national referendum on replacing the current SMP voting system is neither necessary nor desirable. However, to lend it political legitimacy, the adoption of a new electoral system should only be undertaken with the support of MPs from two or more parties that together won over 50% of the votes cast in the last federal election. Introduction Canada’s single-member plurality (SMP) electoral system is fatally flawed. It distorts the true will of Canadian voters, it magnifies regional differences in the country, and it vests excessive political power in the hands of manufactured majority governments, typically elected on a plurality of 40% or less of the popular vote. The adoption of a voting system based on proportional representation would not only address these problems but also improve the quality of democratic government and politics in general. -

Electoral Politics in South Korea

South Korea: Aurel Croissant Electoral Politics in South Korea Aurel Croissant Introduction In December 1997, South Korean democracy faced the fifteenth presidential elections since the Republic of Korea became independent in August 1948. For the first time in almost 50 years, elections led to a take-over of power by the opposition. Simultaneously, the election marked the tenth anniversary of Korean democracy, which successfully passed its first ‘turnover test’ (Huntington, 1991) when elected President Kim Dae-jung was inaugurated on 25 February 1998. For South Korea, which had had six constitutions in only five decades and in which no president had left office peacefully before democratization took place in 1987, the last 15 years have marked a period of unprecedented democratic continuity and political stability. Because of this, some observers already call South Korea ‘the most powerful democracy in East Asia after Japan’ (Diamond and Shin, 2000: 1). The victory of the opposition over the party in power and, above all, the turnover of the presidency in 1998 seem to indicate that Korean democracy is on the road to full consolidation (Diamond and Shin, 2000: 3). This chapter will focus on the role elections and the electoral system have played in the political development of South Korea since independence, and especially after democratization in 1987-88. Five questions structure the analysis: 1. How has the electoral system developed in South Korea since independence in 1948? 2. What functions have elections and electoral systems had in South Korea during the last five decades? 3. What have been the patterns of electoral politics and electoral reform in South Korea? 4. -

An Electoral System Fit for Today? More to Be Done

HOUSE OF LORDS Select Committee on the Electoral Registration and Administration Act 2013 Report of Session 2019–21 An electoral system fit for today? More to be done Ordered to be printed 22 June 2020 and published 8 July 2020 Published by the Authority of the House of Lords HL Paper 83 Select Committee on the Electoral Registration and Administration Act 2013 The Select Committee on the Electoral Registration and Administration Act 2013 was appointed by the House of Lords on 13 June 2019 “to consider post-legislative scrutiny of the Electoral Registration and Administration Act 2013”. Membership The Members of the Select Committee on the Electoral Registration and Administration Act 2013 were: Baroness Adams of Craigielea (from 15 July 2019) Baroness Mallalieu Lord Campbell-Savours Lord Morris of Aberavon (until 14 July 2019) Lord Dykes Baroness Pidding Baroness Eaton Lord Shutt of Greetland (Chairman) Lord Hayward Baroness Suttie Lord Janvrin Lord Wills Lord Lexden Declaration of interests See Appendix 1. A full list of Members’ interests can be found in the Register of Lords’ Interests: http://www.parliament.uk/mps-lords-and-offices/standards-and-interests/register-of-lords- interests Publications All publications of the Committee are available at: https://committees.parliament.uk/committee/405/electoral-registration-and-administration-act- 2013-committee/publications/ Parliament Live Live coverage of debates and public sessions of the Committee’s meetings are available at: http://www.parliamentlive.tv Further information Further information about the House of Lords and its Committees, including guidance to witnesses, details of current inquiries and forthcoming meetings is available at: http://www.parliament.uk/business/lords Committee staff The staff who worked on this Committee were Simon Keal (Clerk), Katie Barraclough (Policy Analyst) and Breda Twomey (Committee Assistant). -

Elections During Crisis: Global Lessons from the Asia-Pacific

Governing During Crises Policy Brief No. 10 Elections During Crisis Global Lessons from the Asia-Pacific 17 March 2021 | Tom Gerald Daly Produced in collaboration with Election Watch and Policy Brief | Election Lessons from the Asia-Pacific Page 1 of 13 Summary _ Key Points This Policy Brief makes the following key points: (a) During 2020 states the world over learned just how challenging it can be to organise full, free, and fair elections in the middle of a pandemic. For many states facing important elections during 2021 (e.g. Japan, the UK, Israel) these challenges remain a pressing concern. (b) The pandemic has spurred electoral innovations and reform worldwide. While reforms in some states garner global attention – such as attempts at wholesale reforms in the US (e.g. early voting) – greater attention should be paid to the Asia-Pacific as a region. (c) A range of positive lessons can be drawn from the conduct of elections in South Korea, New Zealand, Mongolia, and Australia concerning safety measures, effective communication, use of digital technology, advance voting, and postal voting. Innovations across the Asia-Pacific region provide lessons for the world, not only on effectively running elections during a public health emergency, but also pointing to the future of election campaigns, in which early and remote voting becomes more common and online campaigning becomes more central. (d) Experiences elsewhere raise issues to watch out for in forthcoming elections in states and territories undergoing serious ‘pandemic backsliding’ in the protection of political freedoms. Analysis of Singapore and Indonesia indicates a rise in censorship under the pretext of addressing misinformation concerning COVID-19, and (in Indonesia) concerns about ‘vote- buying’ through crisis relief funds. -

Comparative Study of Electoral Systems, 1996-2001

ICPSR 2683 Comparative Study of Electoral Systems, 1996-2001 Virginia Sapiro W. Philips Shively Comparative Study of Electoral Systems 4th ICPSR Version February 2004 Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research P.O. Box 1248 Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106 www.icpsr.umich.edu Terms of Use Bibliographic Citation: Publications based on ICPSR data collections should acknowledge those sources by means of bibliographic citations. To ensure that such source attributions are captured for social science bibliographic utilities, citations must appear in footnotes or in the reference section of publications. The bibliographic citation for this data collection is: Comparative Study of Electoral Systems Secretariat. COMPARATIVE STUDY OF ELECTORAL SYSTEMS, 1996-2001 [Computer file]. 4th ICPSR version. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan, Center for Political Studies [producer], 2002. Ann Arbor, MI: Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research [distributor], 2004. Request for Information on To provide funding agencies with essential information about use of Use of ICPSR Resources: archival resources and to facilitate the exchange of information about ICPSR participants' research activities, users of ICPSR data are requested to send to ICPSR bibliographic citations for each completed manuscript or thesis abstract. Visit the ICPSR Web site for more information on submitting citations. Data Disclaimer: The original collector of the data, ICPSR, and the relevant funding agency bear no responsibility for uses of this collection or for interpretations or inferences based upon such uses. Responsible Use In preparing data for public release, ICPSR performs a number of Statement: procedures to ensure that the identity of research subjects cannot be disclosed. Any intentional identification or disclosure of a person or establishment violates the assurances of confidentiality given to the providers of the information. -

Who Gains from Apparentments Under D'hondt?

CIS Working Paper No 48, 2009 Published by the Center for Comparative and International Studies (ETH Zurich and University of Zurich) Who gains from apparentments under D’Hondt? Dr. Daniel Bochsler University of Zurich Universität Zürich Who gains from apparentments under D’Hondt? Daniel Bochsler post-doctoral research fellow Center for Comparative and International Studies Universität Zürich Seilergraben 53 CH-8001 Zürich Switzerland Centre for the Study of Imperfections in Democracies Central European University Nador utca 9 H-1051 Budapest Hungary [email protected] phone: +41 44 634 50 28 http://www.bochsler.eu Acknowledgements I am in dept to Sebastian Maier, Friedrich Pukelsheim, Peter Leutgäb, Hanspeter Kriesi, and Alex Fischer, who provided very insightful comments on earlier versions of this paper. Manuscript Who gains from apparentments under D’Hondt? Apparentments – or coalitions of several electoral lists – are a widely neglected aspect of the study of proportional electoral systems. This paper proposes a formal model that explains the benefits political parties derive from apparentments, based on their alliance strategies and relative size. In doing so, it reveals that apparentments are most beneficial for highly fractionalised political blocs. However, it also emerges that large parties stand to gain much more from apparentments than small parties do. Because of this, small parties are likely to join in apparentments with other small parties, excluding large parties where possible. These arguments are tested empirically, using a new dataset from the Swiss national parliamentary elections covering a period from 1995 to 2007. Keywords: Electoral systems; apparentments; mechanical effect; PR; D’Hondt. Apparentments, a neglected feature of electoral systems Seat allocation rules in proportional representation (PR) systems have been subject to widespread political debate, and one particularly under-analysed subject in this area is list apparentments. -

A Canadian Model of Proportional Representation by Robert S. Ring A

Proportional-first-past-the-post: A Canadian model of Proportional Representation by Robert S. Ring A thesis submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Political Science Memorial University St. John’s, Newfoundland and Labrador May 2014 ii Abstract For more than a decade a majority of Canadians have consistently supported the idea of proportional representation when asked, yet all attempts at electoral reform thus far have failed. Even though a majority of Canadians support proportional representation, a majority also report they are satisfied with the current electoral system (even indicating support for both in the same survey). The author seeks to reconcile these potentially conflicting desires by designing a uniquely Canadian electoral system that keeps the positive and familiar features of first-past-the- post while creating a proportional election result. The author touches on the theory of representative democracy and its relationship with proportional representation before delving into the mechanics of electoral systems. He surveys some of the major electoral system proposals and options for Canada before finally presenting his made-in-Canada solution that he believes stands a better chance at gaining approval from Canadians than past proposals. iii Acknowledgements First of foremost, I would like to express my sincerest gratitude to my brilliant supervisor, Dr. Amanda Bittner, whose continuous guidance, support, and advice over the past few years has been invaluable. I am especially grateful to you for encouraging me to pursue my Master’s and write about my electoral system idea. -

The Political Business Cycle in Asian Countries

Journal of Business and Economics, ISSN 2155-7950, USA October 2019, Volume 10, No. 10, pp. 966-980 DOI: 10.15341/jbe(2155-7950)/10.10.2019/005 Academic Star Publishing Company, 2019 http://www.academicstar.us The Political Business Cycle in Asian Countries Ling-Chun Hung (Department of Political Science, National Cheng Kung University, Taiwan (R.O.C.)) Abstract: The political business cycle (PBC) theory argues that an incumbent party tends to use government resources to impress voters, so government spending always rises before but declines after an election. Many PBC studies have been done for an individual country or cross-countries, but the results are conflicting. The purpose of this paper is to explore possible fluctuating patterns of government spending in response to political elections in Asian countries because of a lack of studies across this region. In this study, data on 219 elections in 26 countries from 1990 to 2014 are collected. There are two main findings: firstly, government spending falls the year after elections in Asian countries; secondly, the degree of democracy and transparency have impacts on government spending in Asian countries. Key words: political business cycle; election cycle; government spending; government expenditure; Asian JEL code: H51 1. Introduction The political business cycle (PBC) theory has been addressed for four decades. The theory states that an incumbent party will use government resources to impress voters, so economic performance is good before but is poor after an election. However, empirically, scholars have not reach a consensus. Many PBC studies have been done for an individual country or cross-countries, but the results have not been consistent. -

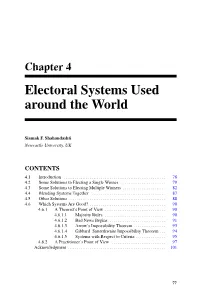

Electoral Systems Used Around the World

Chapter 4 Electoral Systems Used around the World Siamak F. Shahandashti Newcastle University, UK CONTENTS 4.1 Introduction ::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 78 4.2 Some Solutions to Electing a Single Winner :::::::::::::::::::::::: 79 4.3 Some Solutions to Electing Multiple Winners ::::::::::::::::::::::: 82 4.4 Blending Systems Together :::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 87 4.5 Other Solutions :::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 88 4.6 Which Systems Are Good? ::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 90 4.6.1 A Theorist’s Point of View ::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 90 4.6.1.1 Majority Rules ::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 90 4.6.1.2 Bad News Begins :::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 91 4.6.1.3 Arrow’s Impossibility Theorem ::::::::::::::::: 93 4.6.1.4 Gibbard–Satterthwaite Impossibility Theorem ::: 94 4.6.1.5 Systems with Respect to Criteria :::::::::::::::: 95 4.6.2 A Practitioner’s Point of View ::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 97 Acknowledgment ::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 101 77 78 Real-World Electronic Voting: Design, Analysis and Deployment 4.1 Introduction An electoral system, or simply a voting method, defines the rules by which the choices or preferences of voters are collected, tallied, aggregated and collectively interpreted to obtain the results of an election [249, 489]. There are many electoral systems. A voter may be allowed to vote for one or multiple candidates, one or multiple predefined lists of candidates, or state their pref- erence among candidates or predefined lists of candidates. Accordingly, tallying may involve a simple count of the number of votes for each candidate or list, or a relatively more complex procedure of multiple rounds of counting and transferring ballots be- tween candidates or lists. Eventually, the outcome of the tallying and aggregation procedures is interpreted to determine which candidate wins which seat. Designing end-to-end verifiable e-voting schemes is challenging. -

Domestic Constraints on South Korean Foreign Policy

Domestic Constraints on South Korean Foreign Policy January 2018 Domestic Constraints on South Korean Foreign Policy Scott A. Snyder, Geun Lee, Young Ho Kim, and Jiyoon Kim The Council on Foreign Relations (CFR) is an independent, nonpartisan membership organization, think tank, and publisher dedicated to being a resource for its members, government officials, business execu- tives, journalists, educators and students, civic and religious leaders, and other interested citizens in order to help them better understand the world and the foreign policy choices facing the United States and other countries. Founded in 1921, CFR carries out its mission by maintaining a diverse membership, with special programs to promote interest and develop expertise in the next generation of foreign policy leaders; con- vening meetings at its headquarters in New York and in Washington, DC, and other cities where senior government officials, members of Congress, global leaders, and prominent thinkers come together with CFR members to discuss and debate major international issues; supporting a Studies Program that fosters independent research, enabling CFR scholars to produce articles, reports, and books and hold roundtables that analyze foreign policy issues and make concrete policy recommendations; publishing Foreign Affairs, the preeminent journal on international affairs and U.S. foreign policy; sponsoring Independent Task Forces that produce reports with both findings and policy prescriptions on the most important foreign policy topics; and providing up-to-date information and analysis about world events and American foreign policy on its website, CFR.org. The Council on Foreign Relations takes no institutional positions on policy issues and has no affilia- tion with the U.S. -

Appendix A: Electoral Rules

Appendix A: Electoral Rules Table A.1 Electoral Rules for Italy’s Lower House, 1948–present Time Period 1948–1993 1993–2005 2005–present Plurality PR with seat Valle d’Aosta “Overseas” Tier PR Tier bonus national tier SMD Constituencies No. of seats / 6301 / 32 475/475 155/26 617/1 1/1 12/4 districts Election rule PR2 Plurality PR3 PR with seat Plurality PR (FPTP) bonus4 (FPTP) District Size 1–54 1 1–11 617 1 1–6 (mean = 20) (mean = 6) (mean = 4) Note that the acronym FPTP refers to First Past the Post plurality electoral system. 1The number of seats became 630 after the 1962 constitutional reform. Note the period of office is always 5 years or less if the parliament is dissolved. 2Imperiali quota and LR; preferential vote; threshold: one quota and 300,000 votes at national level. 3Hare Quota and LR; closed list; threshold: 4% of valid votes at national level. 4Hare Quota and LR; closed list; thresholds: 4% for lists running independently; 10% for coalitions; 2% for lists joining a pre-electoral coalition, except for the best loser. Ballot structure • Under the PR system (1948–1993), each voter cast one vote for a party list and could express a variable number of preferential votes among candidates of that list. • Under the MMM system (1993–2005), each voter received two separate ballots (the plurality ballot and the PR one) and cast two votes: one for an individual candidate in a single-member district; one for a party in a multi-member PR district. • Under the PR-with-seat-bonus system (2005–present), each voter cast one vote for a party list. -

Who Gains from Apparentments Under D'hondt?

Manuscript Who gains from apparentments under D’Hondt? Daniel Bochsler, Centre for the Study of Imperfections in Democracies (DISC), Central European University, [email protected] - www.bochsler.eu 13 November 2009 Apparentments – or coalitions of several electoral lists – are a widely neglected aspect of the study of proportional electoral systems. This paper proposes a formal model that explains the benefits political parties derive from apparentments, based on their alliance strategies and relative size. In doing so, it reveals that apparentments are most beneficial for highly fractionalised political blocs. However, it also emerges that large parties stand to gain much more from apparentments than small parties do. Because of this, small parties are likely to join in apparentments with other small parties, excluding large parties where possible. These arguments are tested empirically, using a new dataset from the Swiss national parliamentary elections covering a period from 1995 to 2007. Keywords: Electoral systems; apparentments; mechanical effect; PR; D’Hondt. Apparentments, a neglected feature of electoral systems* Seat allocation rules in proportional representation (PR) systems have been subject to widespread political debate, and one particularly under-analysed subject in this area is list apparentments. Theoretical work and studies based on simulation models has shown that the division allocation rule with rounding down (the most frequently applied PR allocation rule, referred to as the D’Hondt or Jefferson method) strongly favours large parties over small parties (see, among many others, Pennisi, 1998; Elklit, 2007; Schuster, Pukelsheim, Drton, and Draper, 2003). Other common seat allocation rules, such as Hamilton’s or Hare/Niemayer’s largest remainder method, or the Sainte- Laguë/Webster divisor method with standard rounding are unbiased with regards to party size.