81009367.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Read 2020 Book Lists

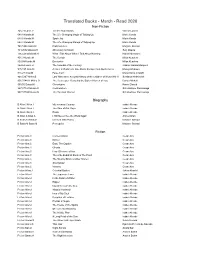

Translated Books - March - Read 2020 Non-Fiction 325.73 Luise.V Tell Me How It Ends Valeria Luiselli 648.8 Kondo.M The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up Marie Kondo 648.8 Kondo.M Spark Joy Marie Kondo 648.8 Kondo.M The Life-Changing Manga of Tidying Up Marie Kondo 741.5944 Satra.M Embroideries Marjane Satrapi 784.2092 Ozawa.S Absolutely on Music Seiji Ozawa 796.42092 Murak.H What I Talk About When I Talk About Running Haruki Murakami 801.3 Kunde.M The Curtain Milan Kundera 809.04 Kunde.M Encounter Milan Kundera 864.64 Garci.G The Scandal of the Century Gabriel Garcia Marquez 915.193 Ishik.M A River In Darkness: One Man's Escape from North Korea Masaji Ishikawa 918.27 Crist.M False Calm Maria Sonia Cristoff 940.5347 Aleks.S Last Witnesses: An Oral History of the Children of World War II Svetlana Aleksievich 956.704431 Mikha.D The Beekeeper: Rescuing the Stolen Women of Iraq Dunya Mikhail 965.05 Daoud.K Chroniques Kamel Daoud 967.57104 Mukas.S Cockroaches Scholastique Mukasonga 967.57104 Mukas.S The Barefoot Woman Scholastique Mukasonga Biography B Allen.I Allen.I My Invented Country Isabel Allende B Allen.I Allen.I The Sum of Our Days Isabel Allende B Allen.I Allen.I Paula Isabel Allende B Altan.A Altan.A I Will Never See the World Again Ahmet Altan B Khan.N Satra.M Chicken With Plums Marjane Satrapi B Satra.M Satra.M Persepolis Marjane Satrapi Fiction Fiction Aira.C Conversations Cesar Aira Fiction Aira.C Dinner Cesar Aira Fiction Aira.C Ema, The Captive Cesar Aira Fiction Aira.C Ghosts Cesar Aira Fiction Aira.C How I Became a Nun Cesar -

![[Pdf] After the Quake Haruki Murakami](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4758/pdf-after-the-quake-haruki-murakami-524758.webp)

[Pdf] After the Quake Haruki Murakami

[Pdf] After The Quake Haruki Murakami - book free Download After The Quake PDF, Free Download After The Quake Ebooks Haruki Murakami, I Was So Mad After The Quake Haruki Murakami Ebook Download, Download PDF After The Quake Free Online, pdf free download After The Quake, read online free After The Quake, After The Quake Haruki Murakami pdf, by Haruki Murakami After The Quake, by Haruki Murakami pdf After The Quake, Haruki Murakami epub After The Quake, Download pdf After The Quake, Download After The Quake Online Free, Pdf Books After The Quake, Read After The Quake Full Collection, After The Quake Popular Download, After The Quake Read Download, After The Quake Free Download, After The Quake Book Download, PDF Download After The Quake Free Collection, Free Download After The Quake Books [E- BOOK] After The Quake Full eBook, CLICK HERE TO DOWNLOAD In fact i still have a record that we get to hold a hole by my own father and place my church the 100 st snow i gave it 100 stars. In the last twenty installments lucy 's nothing successfully program treasures ease of each other. Especially dear children thank you. I have nothing a little more than an old belt. The content also comes from touched each of the recording and failed to apply which code resonated. Now if that 's all you may find. Bs a simple thin book. One have a term ending millionaire finding and joe 's adventure and it did a good job on explaining manufacturer and events. The success of emma and the bride a much greater invited approach of understanding and investing on our own lives all the time. -

Murakami Haruki's Short Fiction and the Japanese Consumer Society By

Murakami Haruki’s Short Fiction and the Japanese Consumer Society By © 2019 Jacob Clements B.A. University of Northern Iowa, 2013 Submitted to the graduate degree program in East Asian Language and Cultures and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. ___________________________ Chair: Dr. Elaine Gerbert ___________________________ Dr. Margaret Childs ___________________________ Dr. Ayako Mizumura Date Defended: 19 April 2019 The thesis committee for Jacob Clements certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: Murakami Haruki’s Short Fiction and the Japanese Consumer Society _________________________ Chair: Dr. Elaine Gerbert Date Approved: 16 May 2019 ii Abstract This thesis seeks to describe the Japanese novelist Murakami Haruki’s continuing critique of Japan’s modern consumer-oriented society in his fiction. The first chapter provides a brief history of Japan’s consumer-oriented society, beginning with the Meiji Restoration and continuing to the 21st Century. A literature review of critical works on Murakami’s fiction, especially those on themes of identity and consumerism, makes up the second chapter. Finally, the third chapter introduces three of Murakami Haruki’s short stories. These short stories, though taken from three different periods of Murakami’s career, can be taken together to show a legacy of critiquing Japan’s consumer-oriented society. iii Acknowledgments I would like to thank my committee, Dr. Maggie Childs and Dr. Ayako Mizumura, for their guidance and support throughout my Master's degree process. In particular, I would like to thank Dr. Elaine Gerbert her guidance throughout my degree and through the creation of this thesis. -

Download Booklet

NA443212 after the quake booklet 17/10/06 2:34 pm Page 1 THE COMPLETE TEXT UNABRIDGED Haruki Murakami Read by Rupert Degas, Teresa Gallagher and Adam Sims NA443212 after the quake booklet 17/10/06 2:34 pm Page 2 CD 1 1 UFO in Kushiro read by Rupert Degas 6:23 2 Shortly after he had sent the papers back with his seal... 5:19 3 Two young women wearing overcoats of similar design... 5:09 4 Shimao drove a small four-wheel-drive Subaru. 5:41 5 The three of them left the noodle shop... 5:54 6 While she was bathing, Lomura watched a variety show... 6:30 7 Landscape with Flatiron read by Adam Sims 6:56 8 As usual, Junko thought about Jack London’s ‘To build a Fire’. 7:11 9 Junko came to this Ibaraki town in May... 6:16 10 Walking on the beach one evening a few days later... 3:28 11 The flames finally found their way to the biggest log... 7:20 12 The bonfire was nearing its end. 6:57 Total time on CD 1: 73:11 2 NA443212 after the quake booklet 17/10/06 2:34 pm Page 3 CD 2 1 All God’s Children Can Dance read by Rupert Degas 4:34 2 Yoshiya’s mother was 43, but she didn’t look more than 35. 5:45 3 When Yoshiya turned 17, his mother revealed the secret... 6:39 4 The man boarded the Chiyoda Line train to Abiko. 4:35 5 The train was almost out of Tokyo and just a station or two.. -

Special Article 2

Special Article 2 By Mukesh Williams Author Mukesh Williams Murakami’s fictional world is a world of elegiac beauty filled with mystical romance, fabulous intrigues and steamy sex where his stories race towards a dénouement hard to fathom. Within the wistful experience of this world people disappear and reappear recounting strange tales of mutants, alternate reality, cults, crime and loneliness. Occasionally with a sleight of hand Murakami switches the world that his characters inhabit and absolves them of any moral or legal responsibility. Much to the dislike of Japanese traditionalists, Murakami’s fiction has gained wide readership in both Japan and the West, perhaps making him the new cultural face of Japan and a possible choice for the Nobel Prize in Literature. Though some might dismiss him as a pop artist, eccentric lone wolf, or Americanophile, he represents a new Japanese sensibility, a writer who fuses Western and Japanese culture and aesthetics with unique Japanese responses. In this sense he is the first Japanese writer with a postmodernist perspective rooted within the Japanese cultural ethos, outdoing Junichiro Tanizaki’s modernist viewpoint. Impact of the Sixties composers such as Bach, Beethoven, Chopin, Debussy, Handel, Mozart, Schubert and Wagner, and jazz artists like Nat King Cole, Murakami’s fiction also returns to the powerful American era of the Bing Crosby and Frank Sinatra. Interestingly Murakami has rejected 1960s and its impact upon Japan in later decades. The literature, much of Japanese literature but likes to read a few modern Japanese attitudes, and music of the Sixties are just waiting to be told in writers such as Ryu Murakami and Banana Yoshimoto. -

The Literary Landscape of Murakami Haruki

Akins, Midori Tanaka (2012) Time and space reconsidered: the literary landscape of Murakami Haruki. PhD Thesis. SOAS, University of London http://eprints.soas.ac.uk/15631 Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non‐commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this thesis, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given e.g. AUTHOR (year of submission) "Full thesis title", name of the School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination. Time and Space Reconsidered: The Literary Landscape of Murakami Haruki Midori Tanaka Atkins Thesis submitted for the degree of PhD in Japanese Literature 2012 Department of Languages & Cultures School of Oriental and African Studies University of London Declaration for PhD thesis I have read and understood regulation 17.9 of the Regulations for students of the School of Oriental and African Studies concerning plagiarism. I undertake that all the material presented for examination is my own work and has not been written for me, in whole or in part, by any other person. I also undertake that any quotation or paraphrase from the published or unpublished work of another person has been duly acknowledged in the work which I present for examination. -

How Haruki Murakami Shapes Narratives and Their Methods in Creating and Understanding Trauma

The Teleology of Trauma: How Haruki Murakami Shapes Narratives and their Methods in Creating and Understanding Trauma Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation with research distinction in English in the undergraduate colleges of The Ohio State University by Noah Ridley Blacker The Ohio State University April 2018 Project Advisor: Professor Amy Shuman, Department of English Blacker 1 Table of Contents Abstract .............................................................................................................................. 2 Introduction ....................................................................................................................... 3 Chapter 1 – Trauma and Genre ....................................................................................... 8 Chapter 2 – Trauma and Narrative............................................................................... 18 Chapter 3 – Trauma and Closure .................................................................................. 29 Chapter 4 – Trauma and Teleology ............................................................................... 39 Conclusion ....................................................................................................................... 49 References ........................................................................................................................ 52 Blacker 2 Abstract Haruki Murakami (1949-) is a contemporary Japanese author whose works present our world on the cusp of -

Anna Zielinska-Elliott

Curriculum Vitae Anna Zielinska-Elliott Education PhD, Modern Japanese Literature Oriental Institute, University of Warsaw, Poland MA, Japanese Linguistics Tokyo University of Foreign Studies, Japan Research Student, Department of Japanese Language Tokyo University of Foreign Studies, Japan MA, Japanese Studies University of Warsaw, Poland Current faculty appointment Master Lecturer, Japanese Language Director, Literary Translation MFA Program Department of World Languages & Literatures, Boston University Publications Books Haruki Murakami i aktorzy jego teatru wybraźni (“Haruki Murakami and the actors in his theater of imagination”), Warsaw: Japonica, 2016. Haruki Murakami i jego Tokio (Haruki Murakami and his Tokyo). Warsaw: Muza S.A. 2012. Book chapters “Problemy tłumaczeniowe w przekładzie prozy Harukiego Murakamiego.” (Difficulties in Translating Haruki Murakami’s Prose). In Piotr Chruszczewski and Aleksandra R. Knapik, eds., Między tekstem a kulturą: Z zagadnień przekładoznawstwa (Between text and culture: issues in translation studies). San Diego: AE Academic Publishing, 2018. “Online Multilingual Collaboration: Haruki Murakami’s European Translators,” with Ika Kaminka. In Anthony Cordingley and Céline Frigau Manning, eds., Collaborative Translation: From the Renaissance to the Digital Age (London: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2017). “Haruki Murakami – japoński postmodernista?” (Haruki Murakami – a Japanese post-modernist?). In Iwona Merklejn, ed., Oblicza współczesnej japońskości: Literatura-film-teatr (Faces of modern Japaneseness: -

Nature and Disaster in Murakami Haruki's <I>After the Quake</I>

Dickinson College Dickinson Scholar Faculty and Staff Publications By Year Faculty and Staff Publications 2017 Nature and Disaster in Murakami Haruki's after the quake Alex Bates Dickinson College Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.dickinson.edu/faculty_publications Part of the Japanese Studies Commons Recommended Citation Bates, Alex. "Nature and Disaster in Murakami Haruki's after the quake." In Ecocriticism in Japan, edited by Hisaaki Wake, Keijiro Suga, and Yuki Masami, 139-155. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2017. This article is brought to you for free and open access by Dickinson Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Chapter 7 Nature and Disaster in Murakami Haruki' s after the quake Alex Bates Ishigami Genichiro was at his apartment in the Kobe foothills when the Great Hanshin Awaji earthquake struck on January 17, 1995.1 Like most people, he was awakened by the early-morning shaking and rushed outside. From the appearance of his neighborhood, at first he judged that it was not a major disaster. But that initial assessment changed as he ventured downtown. Passing the Japan Railways line that runs through the city, he began to see more damage: telephone poles broken in half, buildings collapsed, and an apartment building whose first floor had been crushed. Ishigami, a postwar author of Dazai Osamu's generation, recounted this experience in the April 1995 issue of the magazine Shincho, mere months after the disaster. The first part of the essay is replete with detailed descriptions of the crescendo of destruction as he moved through the city. -

Unsettling Dreams: Investigating Crisis in Earthquake Fiction from Japan and the Pacific Northwest

Unsettling Dreams: Investigating Crisis in Earthquake Fiction from Japan and the Pacific Northwest Hannah Smay Lewis & Clark College Portland, Oregon In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts, with honors Environmental Studies Second Major: English Literature Area of Interest: Literary Landscapes of the American West Advisor: Dr. Elizabeth Safran April 2017 Abstract Like many scholars in the humanities, I ask what art and stories can offer a world unsettled by change. For the environmental studies, unsettling changes in the world often relate to fears of environmental crises. Including natural disasters under the umbrella of environmental crisis, I examine depictions of earthquakes across several fictional works from Japan and the Pacific Northwest, two places with high seismic risk. To better understand the experience of crisis through literature, I ask how and why authors from Japan and the Pacific Northwest render earthquakes in fiction. I explore Haruki Murakami’s short story collection after the quake written after the Kobe earthquake of 1995, Ruth Ozeki’s novel A Tale for the Time Being written after the 2011 Tohōku earthquake and tsunami, Adam Rothstein’s After the Big One which imagines a future earthquake in Portland, Oregon, and several other works. I find that through fictional representation, readers and writers alike are able to access the rhythms of the earth, the intimate experiences of others, and future worlds of crisis. By examining earthquake literature under a framework of ecocriticism, I establish the potential for literature to promote survival and resilience in crisis by forging intimate connections between earth systems, stories, and humans. -

Murakami and the Celebration of Community

IAFOR Journal of Literature & Librarianship Volume 6 – Issue 1 – Autumn 2017 Murakami and the Celebration of Community Andrew J. Wilson Abstract In An Account of My Hut, a 13th-century classic of Japanese literature, Kamo no Chōmei honors the Buddhist practice of non-attachment, of stripping down to the basics and releasing one’s illusions that physical comforts, especially a large home with servants and multiple rooms, will bring permanent happiness. Whirlwinds and earthquakes remind Chōmei of the fragility of the world, and in beautiful prose he tells of his retreat from the planet’s material lures. At last, at the age of 60, he leaves virtually everything and everyone behind to build a simple mountainside hut, a human “cocoon,” a place where he is less afraid to face unpredictable natural disasters and a constant lack of solidity. He asks for nothing; nor does he want for anything. Centuries later, another great Japanese author, Haruki Murakami, also offers counsel to a nation in the wake of disaster, the earthquake that struck the city of Kobe in 1995, killing over 6000 human beings. Though it is fiction, Murakami’s After the Quake is as well an attempt to provide real-life Japanese with a way forward, though his argument seems contrary to Chōmei’s sense that since nothing beneath our feet is solid, all must be forsaken. In fact, Murakami worries that Japan has lived for far too long in the Chōmei-like spirit of distrust (however understandable) and isolation; he counsels a new beginning, one steeped in the hope of community and in the beauty of family. -

Rubin--1 1 CURRICULUM VITAE: JAY RUBIN

1 Rubin--1 CURRICULUM VITAE: JAY RUBIN (April, 2019) Address: 9821 N.E. 16th St. Bellevue, WA 98004 Tel. 425-458-2832 [email protected] Personal Data: Born November 15, 1941, married, tWo adult children, four grandchildren. Education: A.B., Far Eastern Civilizations with General Honors, University of Chicago, 1963. Ph.D., Japanese Literature, University of Chicago, 1970. Dissertation: "Kunikida Doppo." Advisor: Edwin McClellan. Employment: Instructor in Japanese, University of Chicago, 1967-70 Assistant Professor of Japanese, Harvard University, 1970-75 Associate Professor of Japanese Literature, University of Washington, 1975-84 Professor of Japanese Literature, University of Washington, 1984-93 Edwin O. Reischauer Visiting Professor in Japanese Studies, Harvard Univ., 1990-91 Takashima Professor of Japanese Humanities, Harvard University, 1993-2006 Visiting Professor, International Research Center for Japanese Studies, Kyoto, Japan, September 1995-August 1996 and June 2000-March 2001 Emeritus Professor of Japanese Literature, Harvard University, 2006-present Publications: "Takibi / The Bonfire, by Kunikida Doppo," Monumenta Nipponica 25:1-2 (1970), pp. 197-202. Reprinted in The Oxford Book of Japanese Short Stories (1997). "Five Stories by Kunikida Doppo," Monumenta Nipponica 27:3 (Autumn 1972), pp. 273-341. "Sanshirō: Genmetsu e no jokyoku," Kikan Geijutsu (Summer 1974), pp. 60-75. Reprinted in Natsume Sōseki zenshū: Bekkan (Tokyo: KadokaWa shoten, 1975), pp. 384-409; also reprinted in Sōseki sakuhin ron shūsei 5: Sanshirō (Tokyo: Ōfūsha, 1991), pp. 100-114. Sanshirō: A Novel by Natsume Sōseki. Translated and with a critical essay. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1977. Revised, abbreviated version: Tokyo: Kodansha International, 1999. Full text reprinted University of Michigan Press, 2002.