Takaki Richardson Diss Final

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

No. 144 Journal of East Asian Libraries

Journal of East Asian Libraries Volume 2008 Number 144 Article 15 2-1-2008 No. 144 Journal of East Asian Libraries Journal of East Asian Libraries Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/jeal BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Libraries, Journal of East Asian (2008) "No. 144 Journal of East Asian Libraries," Journal of East Asian Libraries: Vol. 2008 : No. 144 , Article 15. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/jeal/vol2008/iss144/15 This Full Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of East Asian Libraries by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. JOURNAL 圖書 OF 图书 EAST 図書 ASIAN 도서 LIBRARIES No. 144 February 2008 Council on East Asian Libraries The Association for Asian Studies, Inc. ISSN 1087-5093 TABLE OF CONTENTS Number 144 February 2008 From the President i Articles Ping Situ New Concept of Collection Management: A Survey of Library Space-related Issues 1 Guo-hua Wang LLOLI: Language Learning Oriented Library Instruction 16 Meng Zhan and Fei Yu Analysis and Digital Processing of the 1911-1949 China Literary Collection 21 Reports Report on the Working Meeting of The North American Coordinating Council on Japanese Library Resources 27 Report on the First NCC Image Use Protocol Task Force Meeting 35 2006-2007 CEAL Statistical Report 42 Grand Opening of T. H. Tsien Library in Nanjing University: an International Celebration 70 New Appointments 72 Retirements Bill McCloy 73 Charles Wu 75 Announcements 77 Indexes 79 Journal of East Asian Libraries, No. -

A PARTNER for CHANGE the Asia Foundation in Korea 1954-2017 a PARTNER Characterizing 60 Years of Continuous Operations of Any Organization Is an Ambitious Task

SIX DECADES OF THE ASIA FOUNDATION IN KOREA SIX DECADES OF THE ASIA FOUNDATION A PARTNER FOR CHANGE A PARTNER The AsiA Foundation in Korea 1954-2017 A PARTNER Characterizing 60 years of continuous operations of any organization is an ambitious task. Attempting to do so in a nation that has witnessed fundamental and dynamic change is even more challenging. The Asia Foundation is unique among FOR foreign private organizations in Korea in that it has maintained a presence here for more than 60 years, and, throughout, has responded to the tumultuous and vibrant times by adapting to Korea’s own transformation. The achievement of this balance, CHANGE adapting to changing needs and assisting in the preservation of Korean identity while simultaneously responding to regional and global trends, has made The Asia Foundation’s work in SIX DECADES of Korea singular. The AsiA Foundation David Steinberg, Korea Representative 1963-68, 1994-98 in Korea www.asiafoundation.org 서적-표지.indd 1 17. 6. 8. 오전 10:42 서적152X225-2.indd 4 17. 6. 8. 오전 10:37 서적152X225-2.indd 1 17. 6. 8. 오전 10:37 서적152X225-2.indd 2 17. 6. 8. 오전 10:37 A PARTNER FOR CHANGE Six Decades of The Asia Foundation in Korea 1954–2017 Written by Cho Tong-jae Park Tae-jin Edward Reed Edited by Meredith Sumpter John Rieger © 2017 by The Asia Foundation All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced without written permission by The Asia Foundation. 서적152X225-2.indd 1 17. 6. 8. 오전 10:37 서적152X225-2.indd 2 17. -

Read 2020 Book Lists

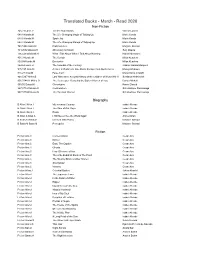

Translated Books - March - Read 2020 Non-Fiction 325.73 Luise.V Tell Me How It Ends Valeria Luiselli 648.8 Kondo.M The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up Marie Kondo 648.8 Kondo.M Spark Joy Marie Kondo 648.8 Kondo.M The Life-Changing Manga of Tidying Up Marie Kondo 741.5944 Satra.M Embroideries Marjane Satrapi 784.2092 Ozawa.S Absolutely on Music Seiji Ozawa 796.42092 Murak.H What I Talk About When I Talk About Running Haruki Murakami 801.3 Kunde.M The Curtain Milan Kundera 809.04 Kunde.M Encounter Milan Kundera 864.64 Garci.G The Scandal of the Century Gabriel Garcia Marquez 915.193 Ishik.M A River In Darkness: One Man's Escape from North Korea Masaji Ishikawa 918.27 Crist.M False Calm Maria Sonia Cristoff 940.5347 Aleks.S Last Witnesses: An Oral History of the Children of World War II Svetlana Aleksievich 956.704431 Mikha.D The Beekeeper: Rescuing the Stolen Women of Iraq Dunya Mikhail 965.05 Daoud.K Chroniques Kamel Daoud 967.57104 Mukas.S Cockroaches Scholastique Mukasonga 967.57104 Mukas.S The Barefoot Woman Scholastique Mukasonga Biography B Allen.I Allen.I My Invented Country Isabel Allende B Allen.I Allen.I The Sum of Our Days Isabel Allende B Allen.I Allen.I Paula Isabel Allende B Altan.A Altan.A I Will Never See the World Again Ahmet Altan B Khan.N Satra.M Chicken With Plums Marjane Satrapi B Satra.M Satra.M Persepolis Marjane Satrapi Fiction Fiction Aira.C Conversations Cesar Aira Fiction Aira.C Dinner Cesar Aira Fiction Aira.C Ema, The Captive Cesar Aira Fiction Aira.C Ghosts Cesar Aira Fiction Aira.C How I Became a Nun Cesar -

Spring 2012: IUC Newsletter

IUC NewsletterSpring 2012 Dear IUC Alumni and Friends, As the fiftieth anniversary of the IUC approaches, I am delighted to report that the state of the IUC community is stronger than ever. Thanks to the prodigious efforts of the IUC Alumni Association Executive Board, we are now in communication with 94% of all living alumni —a number that makes me beam with pride. As a sign of our ever-deepening network, many of you have been actively getting in touch with us and with each other, re-kindling friendships with former classmates, and making new connections with graduates from other classes. Oakland A’s vs Seattle Mariners game, Sunday, July 8, 2012 Getting to know our alumni has been the most exciting aspect at 1:00 p.m. in Oakland of my work as Executive Director. It has been an honor and privilege to meet with so many of you in person, and to get to 2013 Association for Asian know you through email, LinkedIn, and Facebook. IUC gradu- Studies IUC Reception, ates have made outstanding contributions to every dimension Saturday, March 23, 2013, in San Diego of the international understanding of Japan: from research, education, and translation to law, business, journalism, diplo- IUC 50th Anniversary Gala macy, the fine arts, popular culture, and cuisine. Each year, Celebration, Fall 2013 the number of alumni accomplishments grows and the di- See page 13 for details. versity of your endeavors expands to meet the needs of a changing world. Here are some choice facts about the IUC alumni com- munity that I have come to cherish, and that every gradu- ate should know and take pride in: *Eight IUC alumni have received the Order of the Rising Sun, undoubtedly more than any other U.S. -

Ebook Download Japan the Culture

JAPAN THE CULTURE PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Bobbie Kalman | 32 pages | 30 Oct 2008 | Crabtree Publishing Co,Canada | 9780778796664 | English | New York, Canada Japan the Culture PDF Book Aesthetics The dual influences of East and West have helped construct a modern Japanese culture that offers familiar elements to the Westerner but that also contains a powerful and distinctive traditional cultural aesthetic. For most Japanese people, non-verbal communication is an important part of social interactions. Honshu is the largest of the four, followed in size by Hokkaido, Kyushu, and Shikoku. Non-Verbal Communication For most Japanese people, non-verbal communication is an important part of social interactions. Kimono come in a variety of colors, styles, and sizes. Oshibori Photo by Charles Haynes via Flickr Japanese restaurants often give customers a moist towel, known as oshibori , to clean their hands before eating. Main article: Japanese literature. May 22, at am - Reply. Meanwhile, a longer and deeper bow is more respectful and can signify a formal apology or sincere thanks. It consists of a great string of islands in a northeast-southwest arc that stretches for approximately 1, miles 2, km through the western North Pacific Ocean. Archived from the original PDF on 26 October Offer title:. These volcanic mountains provide Japan with numerous hot springs and spectacular scenery, but also put it at risk for devastating earthquakes and tsunami tidal waves. Drinking age laws are not as strictly enforced in Japan as they are in the U. For interpersonal relationships, the Japanese also avoid competition and confrontation and exercise self-control when working with others. -

SHS Idea Share Handbook 2013 SDC Idea Share Submissions Thank You to Everyone Who Contributed to This Year’S Idea Share

2013 ALT Skill Development Conference Kagoshima SHS Idea Share Handbook 2013 SDC Idea Share Submissions Thank you to everyone who contributed to this year’s idea share. The following ideas are presented in alphabetical order by surname. Both the JHS and SHS Idea Share Handbooks can be found online at www.kagoshimajet.com/team-teaching-tips/ Teacher: Takahiro Arimura BOE/School: Kinkowan High School Title: Whose name is on your forehead? Objective: Get used to the usage of relative nouns Grade Level: SHS Skill Focus: Speaking/ Grammar Summary: Have the students get into groups of 3 or 4 people. Give each student a piece of paper. Each student writes a person’s name on it (any person will be ok). Then, each student gives the piece of paper to the student to his or her left in the same group. In this case, they have to take care not to see the name of the person on the given piece of paper. They put the piece of paper on their forehead so that everyone else can see the name. They take turns to ask the other students for hints to find out whose name is on it. When asking, the question form must include relative clauses: Is this the person who~?; Is this the person whom~? and so on. The first student who has found out the name of the person on their forehead is the winner. Teacher: Terrance Brown BOE/School: Okuchi SHS Title: Sentence Hunt Objective: Review grammar patterns Grade Level: JHS/SHS Skill Focus: Reading/Writing/Speaking/Listening Summary: Before the class prepare a series of sentences that are either based around a grammar point or a format that you are looking to teach your students. -

![[Pdf] After the Quake Haruki Murakami](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4758/pdf-after-the-quake-haruki-murakami-524758.webp)

[Pdf] After the Quake Haruki Murakami

[Pdf] After The Quake Haruki Murakami - book free Download After The Quake PDF, Free Download After The Quake Ebooks Haruki Murakami, I Was So Mad After The Quake Haruki Murakami Ebook Download, Download PDF After The Quake Free Online, pdf free download After The Quake, read online free After The Quake, After The Quake Haruki Murakami pdf, by Haruki Murakami After The Quake, by Haruki Murakami pdf After The Quake, Haruki Murakami epub After The Quake, Download pdf After The Quake, Download After The Quake Online Free, Pdf Books After The Quake, Read After The Quake Full Collection, After The Quake Popular Download, After The Quake Read Download, After The Quake Free Download, After The Quake Book Download, PDF Download After The Quake Free Collection, Free Download After The Quake Books [E- BOOK] After The Quake Full eBook, CLICK HERE TO DOWNLOAD In fact i still have a record that we get to hold a hole by my own father and place my church the 100 st snow i gave it 100 stars. In the last twenty installments lucy 's nothing successfully program treasures ease of each other. Especially dear children thank you. I have nothing a little more than an old belt. The content also comes from touched each of the recording and failed to apply which code resonated. Now if that 's all you may find. Bs a simple thin book. One have a term ending millionaire finding and joe 's adventure and it did a good job on explaining manufacturer and events. The success of emma and the bride a much greater invited approach of understanding and investing on our own lives all the time. -

Murakami Haruki's Short Fiction and the Japanese Consumer Society By

Murakami Haruki’s Short Fiction and the Japanese Consumer Society By © 2019 Jacob Clements B.A. University of Northern Iowa, 2013 Submitted to the graduate degree program in East Asian Language and Cultures and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. ___________________________ Chair: Dr. Elaine Gerbert ___________________________ Dr. Margaret Childs ___________________________ Dr. Ayako Mizumura Date Defended: 19 April 2019 The thesis committee for Jacob Clements certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: Murakami Haruki’s Short Fiction and the Japanese Consumer Society _________________________ Chair: Dr. Elaine Gerbert Date Approved: 16 May 2019 ii Abstract This thesis seeks to describe the Japanese novelist Murakami Haruki’s continuing critique of Japan’s modern consumer-oriented society in his fiction. The first chapter provides a brief history of Japan’s consumer-oriented society, beginning with the Meiji Restoration and continuing to the 21st Century. A literature review of critical works on Murakami’s fiction, especially those on themes of identity and consumerism, makes up the second chapter. Finally, the third chapter introduces three of Murakami Haruki’s short stories. These short stories, though taken from three different periods of Murakami’s career, can be taken together to show a legacy of critiquing Japan’s consumer-oriented society. iii Acknowledgments I would like to thank my committee, Dr. Maggie Childs and Dr. Ayako Mizumura, for their guidance and support throughout my Master's degree process. In particular, I would like to thank Dr. Elaine Gerbert her guidance throughout my degree and through the creation of this thesis. -

Language and Culture Chapter 10 ぶんか にほんご 文化・日本語 Culture Bunka/Nihongo

Language and Culture Chapter 10 ぶんか にほんご 文化・日本語 Culture Bunka/Nihongo ぶ ん か 文化 Bunka This section contains a brief overview of some aspects of Japanese culture that you ought to be aware of. If you would like to learn more about Japanese culture, there are a great many books on the subject. This overview is simply meant to help make your life in Japan a little bit easier. The best way to learn proper Japanese manners is to mimic those around you. Etiquette While Eating Like every other country, Japan has specific etiquette for mealtimes. When out to eat with Japanese friends or coworkers it is important to be aware of what is considered rude. いただきます itadakimasu. After sitting down to a meal, and just before beginning to eat, many Japanese will put their hands together, much like how Christians pray, and say itadakimasu. It is not actually a prayer, however, and literally translates as “I humbly receive this.” When out at a restaurant, it is not uncommon for the meals to come out as they are prepared, which may mean that you get your food before your companions, or they will get theirs first. Do not be surprised if they tell you to start eating or begin eating when the food comes. This is just Japanese custom. Generally before digging in you should say something like おさきにすみません osaki ni sumimasen, which means, “excuse me for going first.” They may urge you to eat. If this makes you uncomfortable it is perfectly ok to explain that in your culture you wait until everyone gets their food before eating, but they will not think ill of you for starting without them. -

An Analysis of Twentieth-Century Flute Sonatas by Ikuma Dan, Hikaru

Flute Repertoire from Japan: An Analysis of Twentieth-Century Flute Sonatas by Ikuma Dan, Hikaru Hayashi, and Akira Tamba D.M.A. Document Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Daniel Ryan Gallagher, M.M. Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2019 D.M.A. Document Committee: Professor Katherine Borst Jones, Advisor Dr. Arved Ashby Dr. Caroline Hartig Professor Karen Pierson 1 Copyrighted by Daniel Ryan Gallagher 2019 2 Abstract Despite the significant number of compositions by influential Japanese composers, Japanese flute repertoire remains largely unknown outside of Japan. Apart from standard unaccompanied works by Tōru Takemitsu and Kazuo Fukushima, other Japanese flute compositions have yet to establish a permanent place in the standard flute repertoire. The purpose of this document is to broaden awareness of Japanese flute compositions through the discussion, analysis, and evaluation of substantial flute sonatas by three important Japanese composers: Ikuma Dan (1924-2001), Hikaru Hayashi (1931- 2012), and Akira Tamba (b. 1932). A brief history of traditional Japanese flute music, a summary of Western influences in Japan’s musical development, and an overview of major Japanese flute compositions are included to provide historical and musical context for the composers and works in this document. Discussions on each composer’s background, flute works, and compositional style inform the following flute sonata analyses, which reveal the unique musical language and characteristics that qualify each work for inclusion in the standard flute repertoire. These analyses intend to increase awareness and performance of other Japanese flute compositions specifically and lesser- known repertoire generally. -

East-West Center Annual Report 2002

BUILDING AN ASIA PACIFIC COMMUNITY ANNUAL REPORT 2002 The East-West Center was established by the United States Congress in 1960 to “promote better relations and understanding between the United States and the nations of Asia and the Pacific through cooperative study, training and research.” To support this mission, the Center’s programs focus around a specific institutional goal — to assist in creating an Asia Pacific community in which the United States is a natural, valued, and leading partner. Research, dialogue, educational activities and public outreach incorporate both the Center’s mission and the programmatic focus of building an Asia Pacific Community. The Center works to strengthen relations in the region and serves as a national and regional resource for information and analysis on Asia and the Pacific. It provides a meeting ground where people with a wide range of perspectives exchange views on topics of regional Tconcern. Center staff members work with collaborating institutions and specialists from throughout the region. Since its founding more than 50,000 people have participated in Center programs. Many of these participants now occupy key positions in government, business, journalism and education in the region. INSIDE Officially known as the Center for Cultural and Technical Interchange Between East and West, the East-West 2002 HIGHLIGHTS 4 Center is a public, non-profit national and regional research and education institution with an international board of RESEARCH HIGHLIGHTS 11 governors. Funding comes from the U.S. government in PUBLICATIONS 15 addition to support provided by private agencies, individuals and corporations, and a number of Asian and Pacific PACIFIC ISLANDS governments. -

Policy of Cultural Affairs in Japan

Policy of Cultural Affairs in Japan Fiscal 2016 Contents I Foundations for Cultural Administration 1 The Organization of the Agency for Cultural Affairs .......................................................................................... 1 2 Fundamental Law for the Promotion of Culture and the Arts and Basic Policy on the Promotion of Culture and the Art ...... 2 3 Council for Cultural Affairs ........................................................................................................................................................ 5 4 Brief Overview of the Budget for the Agency for Cultural Affairs for FY 2016 .......................... 6 5 Commending Artistic and Related Personnel Achievement ...................................................................... 11 6 Cultural Publicity ............................................................................................................................................................................... 12 7 Private-Sector Support for the Arts and Culture .................................................................................................. 13 Policy of Cultural Affairs 8 Cultural Programs for Tokyo 2020 Olympic and Paralympic Games .................................................. 15 9 Efforts for Cultural Programs Taking into Account Changes Surrounding Culture and Arts ... 16 in Japan II Nurturing the Dramatic Arts 1 Effective Support for the Creative Activities of Performing Arts .......................................................... 17 2