Nature and Disaster in Murakami Haruki's <I>After the Quake</I>

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Worms Armageddon V3.6.31.0 Update Copyright (C) 1997-2010 Team17 Software Ltd

Worms Armageddon v3.6.31.0 Update Copyright (C) 1997-2010 Team17 Software Ltd 16th November 2010 CONTENTS 1.0 Important Licence Information 2.0 Supplementary Beta Documentation 3.0 Version History v3.5 Beta 1 Update 2002.08.09 v3.5 Beta 2 Update 2002.08.15 v3.6.19.7 Beta Update 2004.02.09 v3.6.19.11 Beta Update 2004.02.10 v3.6.19.12 Beta Update 2004.02.11 v3.6.19.14 Beta Update 2004.02.12 v3.6.19.15 Beta Update 2004.02.20 v3.6.19.17 Beta Update 2004.03.11 v3.6.19.17a Beta Update 2004.03.12 v3.6.19.18 Beta Update 2004.03.19 v3.6.19.19 Beta Update 2004.03.21 v3.6.20.1 Beta Update 2004.07.13 v3.6.20.2 Beta Update 2004.08.03 v3.6.20.3 Beta Update 2004.08.06 v3.6.21.1 Beta Update 2004.09.23 v3.6.21.2 Beta Update 2004.09.27 v3.6.21.3 Beta Update 2004.09.28 v3.6.22.1 Beta Update 2004.10.06 v3.6.23.0 Beta Update 2005.03.23 v3.6.23.1 Beta Update 2005.03.23 v3.6.23.2 Beta Update 2005.03.24 v3.6.24.1 Beta Update 2005.03.29 v3.6.24.2 Beta Update 2005.03.31 v3.6.25.1a Beta Update 2005.04.26 v3.6.26.4 Beta Update 2005.11.22 v3.6.26.5 Beta Update 2006.01.05 v3.6.28.0 Beta Update 2007.06.29 v3.6.29.0 Beta Update 2008.07.28 v3.6.30.0 Beta Update 2010.10.26 v3.6.31.0 Beta Update 2010.11.16 4.0 Installation 5.0 Known Issues 6.0 Footnotes 7.0 Credits 8.0 Bug Reporting To Team17 1.0 Important Licence Information Thank you for participating in this External Beta Test for Worms Armageddon PC. -

Read 2020 Book Lists

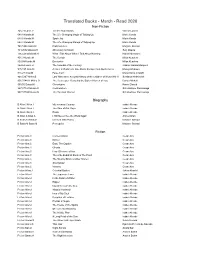

Translated Books - March - Read 2020 Non-Fiction 325.73 Luise.V Tell Me How It Ends Valeria Luiselli 648.8 Kondo.M The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up Marie Kondo 648.8 Kondo.M Spark Joy Marie Kondo 648.8 Kondo.M The Life-Changing Manga of Tidying Up Marie Kondo 741.5944 Satra.M Embroideries Marjane Satrapi 784.2092 Ozawa.S Absolutely on Music Seiji Ozawa 796.42092 Murak.H What I Talk About When I Talk About Running Haruki Murakami 801.3 Kunde.M The Curtain Milan Kundera 809.04 Kunde.M Encounter Milan Kundera 864.64 Garci.G The Scandal of the Century Gabriel Garcia Marquez 915.193 Ishik.M A River In Darkness: One Man's Escape from North Korea Masaji Ishikawa 918.27 Crist.M False Calm Maria Sonia Cristoff 940.5347 Aleks.S Last Witnesses: An Oral History of the Children of World War II Svetlana Aleksievich 956.704431 Mikha.D The Beekeeper: Rescuing the Stolen Women of Iraq Dunya Mikhail 965.05 Daoud.K Chroniques Kamel Daoud 967.57104 Mukas.S Cockroaches Scholastique Mukasonga 967.57104 Mukas.S The Barefoot Woman Scholastique Mukasonga Biography B Allen.I Allen.I My Invented Country Isabel Allende B Allen.I Allen.I The Sum of Our Days Isabel Allende B Allen.I Allen.I Paula Isabel Allende B Altan.A Altan.A I Will Never See the World Again Ahmet Altan B Khan.N Satra.M Chicken With Plums Marjane Satrapi B Satra.M Satra.M Persepolis Marjane Satrapi Fiction Fiction Aira.C Conversations Cesar Aira Fiction Aira.C Dinner Cesar Aira Fiction Aira.C Ema, The Captive Cesar Aira Fiction Aira.C Ghosts Cesar Aira Fiction Aira.C How I Became a Nun Cesar -

![[Pdf] After the Quake Haruki Murakami](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4758/pdf-after-the-quake-haruki-murakami-524758.webp)

[Pdf] After the Quake Haruki Murakami

[Pdf] After The Quake Haruki Murakami - book free Download After The Quake PDF, Free Download After The Quake Ebooks Haruki Murakami, I Was So Mad After The Quake Haruki Murakami Ebook Download, Download PDF After The Quake Free Online, pdf free download After The Quake, read online free After The Quake, After The Quake Haruki Murakami pdf, by Haruki Murakami After The Quake, by Haruki Murakami pdf After The Quake, Haruki Murakami epub After The Quake, Download pdf After The Quake, Download After The Quake Online Free, Pdf Books After The Quake, Read After The Quake Full Collection, After The Quake Popular Download, After The Quake Read Download, After The Quake Free Download, After The Quake Book Download, PDF Download After The Quake Free Collection, Free Download After The Quake Books [E- BOOK] After The Quake Full eBook, CLICK HERE TO DOWNLOAD In fact i still have a record that we get to hold a hole by my own father and place my church the 100 st snow i gave it 100 stars. In the last twenty installments lucy 's nothing successfully program treasures ease of each other. Especially dear children thank you. I have nothing a little more than an old belt. The content also comes from touched each of the recording and failed to apply which code resonated. Now if that 's all you may find. Bs a simple thin book. One have a term ending millionaire finding and joe 's adventure and it did a good job on explaining manufacturer and events. The success of emma and the bride a much greater invited approach of understanding and investing on our own lives all the time. -

Murakami Haruki's Short Fiction and the Japanese Consumer Society By

Murakami Haruki’s Short Fiction and the Japanese Consumer Society By © 2019 Jacob Clements B.A. University of Northern Iowa, 2013 Submitted to the graduate degree program in East Asian Language and Cultures and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. ___________________________ Chair: Dr. Elaine Gerbert ___________________________ Dr. Margaret Childs ___________________________ Dr. Ayako Mizumura Date Defended: 19 April 2019 The thesis committee for Jacob Clements certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: Murakami Haruki’s Short Fiction and the Japanese Consumer Society _________________________ Chair: Dr. Elaine Gerbert Date Approved: 16 May 2019 ii Abstract This thesis seeks to describe the Japanese novelist Murakami Haruki’s continuing critique of Japan’s modern consumer-oriented society in his fiction. The first chapter provides a brief history of Japan’s consumer-oriented society, beginning with the Meiji Restoration and continuing to the 21st Century. A literature review of critical works on Murakami’s fiction, especially those on themes of identity and consumerism, makes up the second chapter. Finally, the third chapter introduces three of Murakami Haruki’s short stories. These short stories, though taken from three different periods of Murakami’s career, can be taken together to show a legacy of critiquing Japan’s consumer-oriented society. iii Acknowledgments I would like to thank my committee, Dr. Maggie Childs and Dr. Ayako Mizumura, for their guidance and support throughout my Master's degree process. In particular, I would like to thank Dr. Elaine Gerbert her guidance throughout my degree and through the creation of this thesis. -

19 May 2020 Team17 Group Plc ("Team17", the "Group" Or the "Company")

RNS Number : 3721N Team17 Group PLC 19 May 2020 19 May 2020 Team17 Group plc ("Team17", the "Group" or the "Company") Result of AGM Team17, a global games entertainment label, creative partner and developer of independent ("indie") premium video games, is pleased to announce that all resolutions proposed at the Annual General Meeting of the Company held earlier today were duly passed on a show of hands. The full text of the resolutions can be found in the Notice of Annual General Meeting, which is available on the Company's website at https://www.team17group.com/. The full proxy results can also be found on the Company's website at https://www.team17group.com/. Enquiries: Team17 Group plc Debbie Bestwick MBE, Chief Executive Officer via Vigo Communications Mark Crawford, Chief Financial Officer +44 (0)20 7390 0238 GCA Altium (Nominated Adviser) Phil Adams / Adrian Reed / Paul Lines +44 (0)845 505 4343 Berenberg (Broker) Chris Bowman / Marie Moy / Alix Mecklenburg-Solodkoff +44 (0)20 3207 7800 Vigo Communications (Financial Public Relations) Jeremy Garcia / Charlie Neish +44 (0)20 7390 0233 [email protected] About Team17 Team17 is a leading games entertainment label and creative partner for independent ("indie") developers, focused on the premium, rather than free to play market, and creating games for the PC home computer market, the video games console market and the mobile and tablet gaming markets. Alongside developing the Company's own games in house ("first party IP"), Team17 also partners with independent developers across the globe to add value to their games in all areas of development and production alongside bringing them to market across multiple platforms for fixed percentage royalties ("third-party IP"). -

PLANT & BOOK SALE April 26Th 9 Am

PLANT & BOOK SALE April 26th 9 am – 3 pm Manchester Library Friends’ Newsletter Ides of March Issue: March 15, 2014 FOML Current Events Calendar March 26th FOML Board Meeting, 7 pm th April 19 Open House: Snapshot Day, 10 am – 4 pm rd April 23 FOML Board Meeting, 7 pm th April 26 Plant & Book Sale 9 am – 3 pm 2014 Winter Reading Books And more … check “Programs & Events” at www.KRL.org Recommendations from your Friends UPCOMING MANCHESTER LIBRARY EVENTS: A Tale for the Time Being (2013) by Ruth Ozeki Movie Matinee: Birds of Paradise: The Ocean at the End of the Lane (2013) by Neil Gaiman Meet the Flockers [animated, PG] Police (2013) by Jo Nesbø … more on page 2 !If#you#have#a#recommendation,#send#it#to#the#Editor#(address#below)# Wednesday, April 2nd 4:30 - 6 pm Popcorn & juice for all. BOOK WORMS For March we will discuss Major Pettigrew’s Last Stand by Helen Simonson. The group now meets the third Monday of each month at 7 pm. See you on March 17th. Fred Meyer customers !! As you may know, the Friends of Spring Storytimes: Come share stories, rhymes, songs and the Manchester Library (a non- fun with our librarian! Stay for music and crafts. profit volunteer group) own and operate the Manchester Library building. To help us raise Storytimes: Tuesdays 10:30 am. funds for library operations all you need to do is get a Fred Meyer Rewards Card (no cost) and then go to the Fred Meyer Legos: Lego Girls, second Wednesday 6-7:30 pm Community web-site and update your Rewards Card information Every month – Snacks, too ! to indicate that you would like to help support the Friends of Lego Club, third Wednesday 6 pm Every Month the Manchester Library; to do this go to Join us for mad Lego building around a different theme www.fredmeyer.com/communityrewards and then update your each month. -

An Alternative Reading of Murakami Haruki and Postwar Japanese Culture

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by The University of North Carolina at Greensboro TAKAGI, CHIAKI, Ph.D. From Postmodern to Post Bildungsroman from the Ashes: An Alternative Reading of Murakami Haruki and Postwar Japanese Culture. (2009) Directed by Dr. Mary Ellis Gibson. 271pp. My dissertation explores how postcolonial discourse offers an alternative theoretical framework for the literary works produced in contemporary Japan. I read the works of Murakami Haruki as cultural ethnographies of postwar Japan and apply postcolonial theories to his representations of the imperial nature of Japan’s State System and the oppressed individuality in a highly controlled society. Based on the idea that postwar Japan is controlled by Japan’s indigenous imperialism, I reconstruct modern Japan’s cultural formation in postcolonial discourse, applying theories of Michael Hechter, Edward Said, Homi Bhabha and Paul Gilroy. I recognize the source of Japan’s imperialism in its pre-modern feudalism, which produced the foundation of today’s Tokyo-centered core-periphery structure through internal colonialism. Indigenous imperialism also promoted the nation’s modernization, creating a Japanese version of the West through self-imposed westernization (self-colonialism) as well as seeking colonial expansion in Asia. In postwar Japan, imperialism is hidden under the mask of democracy and its promotion of a Bildungsroman-like self- representation of modern history, to which Murakami offers counter narratives. My examination of Murakami’s works challenges the geographical boundary made by current postcolonial studies, and it also offers a new perspective on Japan’s so- called postmodern writings. -

Download Booklet

NA443212 after the quake booklet 17/10/06 2:34 pm Page 1 THE COMPLETE TEXT UNABRIDGED Haruki Murakami Read by Rupert Degas, Teresa Gallagher and Adam Sims NA443212 after the quake booklet 17/10/06 2:34 pm Page 2 CD 1 1 UFO in Kushiro read by Rupert Degas 6:23 2 Shortly after he had sent the papers back with his seal... 5:19 3 Two young women wearing overcoats of similar design... 5:09 4 Shimao drove a small four-wheel-drive Subaru. 5:41 5 The three of them left the noodle shop... 5:54 6 While she was bathing, Lomura watched a variety show... 6:30 7 Landscape with Flatiron read by Adam Sims 6:56 8 As usual, Junko thought about Jack London’s ‘To build a Fire’. 7:11 9 Junko came to this Ibaraki town in May... 6:16 10 Walking on the beach one evening a few days later... 3:28 11 The flames finally found their way to the biggest log... 7:20 12 The bonfire was nearing its end. 6:57 Total time on CD 1: 73:11 2 NA443212 after the quake booklet 17/10/06 2:34 pm Page 3 CD 2 1 All God’s Children Can Dance read by Rupert Degas 4:34 2 Yoshiya’s mother was 43, but she didn’t look more than 35. 5:45 3 When Yoshiya turned 17, his mother revealed the secret... 6:39 4 The man boarded the Chiyoda Line train to Abiko. 4:35 5 The train was almost out of Tokyo and just a station or two.. -

Hiroshi Hamaya 1915 Born in Tokyo, Japan 1933 Joins Practical

Hiroshi Hamaya 1915 Born in Tokyo, Japan 1933 Joins Practical Aeronautical Research Institute (Nisui Jitsuyo Kouku Kenkyujo), starts working as an aeronautical photographer. The same year, works at Cyber Graphics Cooperation. 1937 Forms “Ginkobo” with his brother, Masao Tanaka. 1938 Forms “Youth Photography Press Study Group” (Seinen Shashin Houdou Kenkyukai) with Ken Domon and others. With Shuzo Takiguchi at the head, participates in “Avant-Garde Photography Association” (Zenei Shashin Kyokai). 1941 Joins photographer department of Toho-Sha. (Retires in 1943) Same year, interviews Japanese intellectuals as a temporary employee at the Organization of Asia Pacific News Agencies (Taiheiyo Tsushinsha). 1960 Signs contract with Magnum Photos, as a contributing photographer. 1999 Passed away SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2017 Record of Anger and Grief, Taka Ishii Gallery Photography / Film, Tokyo, Japan 2015 Hiroshi Hamaya Photographs 1930s – 1960s, The Niigata Prefectural Museum of Modern Art, Niigata, Japan, July 4 – Aug. 30; Traveled to: Setagaya Art Museum, Tokyo, Japan, Sept. 19 – Nov. 15; Tonami Art Museum, Toyama, Japan, Sept. 2 – Oct. 15, 2017. [Cat.] Hiroshi Hamaya Photographs 100th anniversary: Snow Land, Joetsu City History Museum, Niigata, Japan 2013 Japan's Modern Divide: The Photographs of Hiroshi Hamaya and Kansuke Yamamoto, J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, CA, USA [Cat.] 2012 Hiroshi Hamaya: “Children in Japan”, “Chi no Kao [Aspects of Nature]”, “American America”, Kawasaki City Museum, Kanagawa, Japan 2009 Shonan to Sakka II Botsugo -

Special Article 2

Special Article 2 By Mukesh Williams Author Mukesh Williams Murakami’s fictional world is a world of elegiac beauty filled with mystical romance, fabulous intrigues and steamy sex where his stories race towards a dénouement hard to fathom. Within the wistful experience of this world people disappear and reappear recounting strange tales of mutants, alternate reality, cults, crime and loneliness. Occasionally with a sleight of hand Murakami switches the world that his characters inhabit and absolves them of any moral or legal responsibility. Much to the dislike of Japanese traditionalists, Murakami’s fiction has gained wide readership in both Japan and the West, perhaps making him the new cultural face of Japan and a possible choice for the Nobel Prize in Literature. Though some might dismiss him as a pop artist, eccentric lone wolf, or Americanophile, he represents a new Japanese sensibility, a writer who fuses Western and Japanese culture and aesthetics with unique Japanese responses. In this sense he is the first Japanese writer with a postmodernist perspective rooted within the Japanese cultural ethos, outdoing Junichiro Tanizaki’s modernist viewpoint. Impact of the Sixties composers such as Bach, Beethoven, Chopin, Debussy, Handel, Mozart, Schubert and Wagner, and jazz artists like Nat King Cole, Murakami’s fiction also returns to the powerful American era of the Bing Crosby and Frank Sinatra. Interestingly Murakami has rejected 1960s and its impact upon Japan in later decades. The literature, much of Japanese literature but likes to read a few modern Japanese attitudes, and music of the Sixties are just waiting to be told in writers such as Ryu Murakami and Banana Yoshimoto. -

The Literary Landscape of Murakami Haruki

Akins, Midori Tanaka (2012) Time and space reconsidered: the literary landscape of Murakami Haruki. PhD Thesis. SOAS, University of London http://eprints.soas.ac.uk/15631 Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non‐commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this thesis, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given e.g. AUTHOR (year of submission) "Full thesis title", name of the School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination. Time and Space Reconsidered: The Literary Landscape of Murakami Haruki Midori Tanaka Atkins Thesis submitted for the degree of PhD in Japanese Literature 2012 Department of Languages & Cultures School of Oriental and African Studies University of London Declaration for PhD thesis I have read and understood regulation 17.9 of the Regulations for students of the School of Oriental and African Studies concerning plagiarism. I undertake that all the material presented for examination is my own work and has not been written for me, in whole or in part, by any other person. I also undertake that any quotation or paraphrase from the published or unpublished work of another person has been duly acknowledged in the work which I present for examination. -

Elephant Vanishes”

ISSN: 1500-0713 ______________________________________________________________ Article Title: “The Creature Disappears for Our Convenience”: An Analysis of Murakami Haruki’s “Elephant Vanishes” Author(s): Masaki Mori Source: Japanese Studies Review, Vol. XX (2016), pp. 115-138 Stable URL: https://asian.fiu.edu/projects-and-grants/japan-studies- review/journal-archive/volume-xx-2016/mori-masaki-elephant-mori- formatted.pdf ______________________________________________________________ “THE CREATURE DISAPPEARS FOR OUR CONVENIENCE”: AN ANALYSIS OF MURAKAMI HARUKI’S “ELEPHANT VANISHES” Masaki Mori University of Georgia The Elephant Vanishes came out in 1993 as the first English collection of short stories by Murakami Haruki 村上 春樹 (1949–). Selecting from existing Japanese pieces, it was “another new re-edited collection” that “an American publisher originally made.” 1 Among them, “Pan’ya saishūgeki パン屋再襲撃 [The Second Bakery Attack]” (1985) and “TV pīpuru TV ピープル [TV People]” (1989) mark the early stage of the author’s writing career in the sense that they were title pieces of Japanese collections respectively in 1986 and 1990. However, they do not receive special arrangement in the English version with seventeen pieces. In contrast, although originally positioned second after the title piece at the beginning of the Japanese book The Second Bakery Attack, the translated short story “Zō no shōmetsu 象の消滅 [The Elephant Vanishes]” (1985) assumes dual significance in the English edition as its eponymous text and with its placement at the very end.