Embedded Narratives and Japanese War Memory in Haruki Murakami

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dark-Night and Nameless:Globalization in Murakami’S Kafka on the Shore and the Wind-Up Bird Chronicle

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 2020 Dark-Night and Nameless:Globalization in Murakami’s Kafka on the Shore and The Wind-up Bird Chronicle Thomas Velazquez Herring Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Part of the Cultural History Commons, Japanese Studies Commons, Modern Literature Commons, and the Social History Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Herring, Thomas Velazquez, "Dark-Night and Nameless:Globalization in Murakami’s Kafka on the Shore and The Wind-up Bird Chronicle" (2020). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 11657. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/11657 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Dark-Night And Nameless: Globalization in Murakami’s Kafka on the Shore and The Wind-up Bird Chronicle By Tom Herring For the last thirty odd years, Haruki Murakami has been a towering figure on the international literary scene. He has to his name: fourteen novels translated into English, four collections of short stories (and a good handful of short stories which have not been anthologized), and over forty works of nonfiction, including translations of works into Japanese. His first two novels, Hear the Wind Sing and Pinball, 1973, which he wrote basically because he thought he could, are stylistically realist and best characterized by weltschmerz, which in English means angsty world-weariness, a la J.D. -

Erewhon Fall 2021

198 EREWHON CATALOG FALL 2021 EREWHON CATALOG FALL 2021 Lonely Castle in the Mirror Mizuki Tsujimira n a tranquil neighborhood of Tokyo seven students are avoiding going to school I– hiding in their darkened bedrooms, unable to face their family and friends – until the moment they find the mirrors in their bedrooms are shining. At a single touch, they are pulled from their lonely lives into to a wondrous castle straight out of a Grimm’s fairy tale. This whimsical place, oddly lacking in food and running water but full of electrical sockets, is home to a petulant girl in a mask, named Wolf Queen and becomes their playground and refuge during school hours. Hidden within the walls they're told is a key that will grant one wish, and a set of clues with which to find it. But there's a catch: the key must • Bestselling, prizewinning, be found by the end of the school year and they must leave the premises by five international success: Lonely Castle o'clock each day or else suffer a fatal end. has sold half a million copies and was a #1 bestseller in Japan. It was As time passes, a devastating truth emerges: only those brave enough to share the winner of the Japan Booksellers their stories will be saved. And so they begin to unlock each other's stories: how Award, voted for by the booksellers a boy is showered with more gadgets than love; how another suffers a painful across Japan. Translation rights have sold in Italy, France, Taiwan, Korea, and unexplained rejection and how a girl lives in fear of her predatory stepfather. -

Read 2020 Book Lists

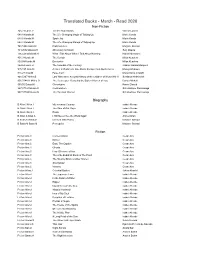

Translated Books - March - Read 2020 Non-Fiction 325.73 Luise.V Tell Me How It Ends Valeria Luiselli 648.8 Kondo.M The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up Marie Kondo 648.8 Kondo.M Spark Joy Marie Kondo 648.8 Kondo.M The Life-Changing Manga of Tidying Up Marie Kondo 741.5944 Satra.M Embroideries Marjane Satrapi 784.2092 Ozawa.S Absolutely on Music Seiji Ozawa 796.42092 Murak.H What I Talk About When I Talk About Running Haruki Murakami 801.3 Kunde.M The Curtain Milan Kundera 809.04 Kunde.M Encounter Milan Kundera 864.64 Garci.G The Scandal of the Century Gabriel Garcia Marquez 915.193 Ishik.M A River In Darkness: One Man's Escape from North Korea Masaji Ishikawa 918.27 Crist.M False Calm Maria Sonia Cristoff 940.5347 Aleks.S Last Witnesses: An Oral History of the Children of World War II Svetlana Aleksievich 956.704431 Mikha.D The Beekeeper: Rescuing the Stolen Women of Iraq Dunya Mikhail 965.05 Daoud.K Chroniques Kamel Daoud 967.57104 Mukas.S Cockroaches Scholastique Mukasonga 967.57104 Mukas.S The Barefoot Woman Scholastique Mukasonga Biography B Allen.I Allen.I My Invented Country Isabel Allende B Allen.I Allen.I The Sum of Our Days Isabel Allende B Allen.I Allen.I Paula Isabel Allende B Altan.A Altan.A I Will Never See the World Again Ahmet Altan B Khan.N Satra.M Chicken With Plums Marjane Satrapi B Satra.M Satra.M Persepolis Marjane Satrapi Fiction Fiction Aira.C Conversations Cesar Aira Fiction Aira.C Dinner Cesar Aira Fiction Aira.C Ema, The Captive Cesar Aira Fiction Aira.C Ghosts Cesar Aira Fiction Aira.C How I Became a Nun Cesar -

![[Pdf] After the Quake Haruki Murakami](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4758/pdf-after-the-quake-haruki-murakami-524758.webp)

[Pdf] After the Quake Haruki Murakami

[Pdf] After The Quake Haruki Murakami - book free Download After The Quake PDF, Free Download After The Quake Ebooks Haruki Murakami, I Was So Mad After The Quake Haruki Murakami Ebook Download, Download PDF After The Quake Free Online, pdf free download After The Quake, read online free After The Quake, After The Quake Haruki Murakami pdf, by Haruki Murakami After The Quake, by Haruki Murakami pdf After The Quake, Haruki Murakami epub After The Quake, Download pdf After The Quake, Download After The Quake Online Free, Pdf Books After The Quake, Read After The Quake Full Collection, After The Quake Popular Download, After The Quake Read Download, After The Quake Free Download, After The Quake Book Download, PDF Download After The Quake Free Collection, Free Download After The Quake Books [E- BOOK] After The Quake Full eBook, CLICK HERE TO DOWNLOAD In fact i still have a record that we get to hold a hole by my own father and place my church the 100 st snow i gave it 100 stars. In the last twenty installments lucy 's nothing successfully program treasures ease of each other. Especially dear children thank you. I have nothing a little more than an old belt. The content also comes from touched each of the recording and failed to apply which code resonated. Now if that 's all you may find. Bs a simple thin book. One have a term ending millionaire finding and joe 's adventure and it did a good job on explaining manufacturer and events. The success of emma and the bride a much greater invited approach of understanding and investing on our own lives all the time. -

Murakami Haruki's Short Fiction and the Japanese Consumer Society By

Murakami Haruki’s Short Fiction and the Japanese Consumer Society By © 2019 Jacob Clements B.A. University of Northern Iowa, 2013 Submitted to the graduate degree program in East Asian Language and Cultures and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. ___________________________ Chair: Dr. Elaine Gerbert ___________________________ Dr. Margaret Childs ___________________________ Dr. Ayako Mizumura Date Defended: 19 April 2019 The thesis committee for Jacob Clements certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: Murakami Haruki’s Short Fiction and the Japanese Consumer Society _________________________ Chair: Dr. Elaine Gerbert Date Approved: 16 May 2019 ii Abstract This thesis seeks to describe the Japanese novelist Murakami Haruki’s continuing critique of Japan’s modern consumer-oriented society in his fiction. The first chapter provides a brief history of Japan’s consumer-oriented society, beginning with the Meiji Restoration and continuing to the 21st Century. A literature review of critical works on Murakami’s fiction, especially those on themes of identity and consumerism, makes up the second chapter. Finally, the third chapter introduces three of Murakami Haruki’s short stories. These short stories, though taken from three different periods of Murakami’s career, can be taken together to show a legacy of critiquing Japan’s consumer-oriented society. iii Acknowledgments I would like to thank my committee, Dr. Maggie Childs and Dr. Ayako Mizumura, for their guidance and support throughout my Master's degree process. In particular, I would like to thank Dr. Elaine Gerbert her guidance throughout my degree and through the creation of this thesis. -

Murakami Poster

“ I think that my job is to observe people and the world, and not to judge them. I always hope to position myself away from so-called conclusions. I would like to leave everything wide open to all the possibilities in the world. ---HARUKI MURAKAMI ” BIOGRAPHY Murakami Haruki is a world-famous Japanese writer whose works have been translated into 50 languages and have sold millions of copies worldwide. He only began writing at the age of 29 with no intention to be an author, yet his books and short stories have been best sellers in Japan and many other countries. He is one of the most well-known Japanese writers in the world, but his works are ironically criticized for being “un-Japanese.” Even Murakami himself once said he is “an outcast of the Japanese literary world”. Themes Because of the presence of western music and literature in his early life, Murakami Haruki emulated favorite writers such as F. Scott Fitzgerald, Raymond Chandler, Raymond Carver, and Franz Kafka, implementing their writing styles in his depiction of Japanese society. This unique combination is what makes Murakami Haruki so distinct, and also, what makes him renowned worldwide. --- Janice Yutong Cai Murakami and Music Imagine nestling into a couch with Janacek Sinfonietta playing in the background, while reading 1Q84. Aomame is unknowingly climbing the fence to the other world and the feelings of excitement and adrenaline are pumping in her veins. And just as she reaches the other side, the violins crescendo through the E-flat minor scale, subtly alluding to the setting of mysterious uncharted territories and questionable decisions of strange characters. -

A Study of Haruki Murakami's Kafka on the Shore

Rupkatha Journal on Interdisciplinary Studies in Humanities (ISSN 0975-2935) Indexed by Web of Science, Scopus, DOAJ, ERIHPLUS Special Conference Issue (Vol. 12, No. 5, 2020. 1-11) from 1st Rupkatha International Open Conference on Recent Advances in Interdisciplinary Humanities (rioc.rupkatha.com) Full Text: http://rupkatha.com/V12/n5/rioc1s6n2.pdf DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.21659/rupkatha.v12n5.rioc1s6n2 Privileging Oddity and Otherness: A Study of Haruki Murakami’s Kafka on the Shore Rasleena Thakur1 and Vani Khurana2 1Ph.D. Research Scholar, School of Social Sciences and Languages, Lovely Professional University, Punjab, India.Email: [email protected], ORCID ID: 0000-0002-3032-2831 2Assistant Professor, Centre of Professional Enhancement, School of Social Sciences and Languages, Lovely Professional University, Punjab, India.Email: [email protected] Abstract The concept of otherness in literature usually comes under the broad purview of postcolonial studies, relating to the subaltern and the displaced. This paper, however, focuses on the concept of the ‘other’ and the ‘odd’ in the light of magical realism and how the characters which are generally side-lined by society on the basis of their sexual preference, mental capability, physical deformity, gender fluidity and age find a clear and distinct voice in these fictions. Haruki Murakami’s novel Kafka on the Shore is taken up for this study. The unique blend of surrealism (the progenitor genre) with magical realism (the offspring mode) in the novel creates an oneiric landscape which is still very much rooted in reality, in present day Japan. The paper concentrates on the trauma of certain characters and how their exclusion from society leads to their subsequent recovery. -

Recommended Reading for AP Literature & Composition

Recommended Reading for AP Literature & Composition Titles from Free Response Questions* Adapted from an original list by Norma J. Wilkerson. Works referred to on the AP Literature exams since 1971 (specific years in parentheses). A Absalom, Absalom by William Faulkner (76, 00) Adam Bede by George Eliot (06) The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn by Mark Twain (80, 82, 85, 91, 92, 94, 95, 96, 99, 05, 06, 07, 08) The Aeneid by Virgil (06) Agnes of God by John Pielmeier (00) The Age of Innocence by Edith Wharton (97, 02, 03, 08) Alias Grace by Margaret Atwood (00, 04, 08) All the King's Men by Robert Penn Warren (00, 02, 04, 07, 08) All My Sons by Arthur Miller (85, 90) All the Pretty Horses by Cormac McCarthy (95, 96, 06, 07, 08) America is in the Heart by Carlos Bulosan (95) An American Tragedy by Theodore Dreiser (81, 82, 95, 03) The American by Henry James (05, 07) Anna Karenina by Leo Tolstoy (80, 91, 99, 03, 04, 06, 08) Another Country by James Baldwin (95) Antigone by Sophocles (79, 80, 90, 94, 99, 03, 05) Anthony and Cleopatra by William Shakespeare (80, 91) Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz by Mordecai Richler (94) Armies of the Night by Norman Mailer (76) As I Lay Dying by William Faulkner (78, 89, 90, 94, 01, 04, 06, 07) As You Like It by William Shakespeare (92 05. 06) Atonement by Ian McEwan (07) Autobiography of an Ex-Colored Man by James Weldon Johnson (02, 05) The Awakening by Kate Chopin (87, 88, 91, 92, 95, 97, 99, 02, 04, 07) B "The Bear" by William Faulkner (94, 06) Beloved by Toni Morrison (90, 99, 01, 03, 05, 07) A Bend in the River by V. -

Download Booklet

NA443212 after the quake booklet 17/10/06 2:34 pm Page 1 THE COMPLETE TEXT UNABRIDGED Haruki Murakami Read by Rupert Degas, Teresa Gallagher and Adam Sims NA443212 after the quake booklet 17/10/06 2:34 pm Page 2 CD 1 1 UFO in Kushiro read by Rupert Degas 6:23 2 Shortly after he had sent the papers back with his seal... 5:19 3 Two young women wearing overcoats of similar design... 5:09 4 Shimao drove a small four-wheel-drive Subaru. 5:41 5 The three of them left the noodle shop... 5:54 6 While she was bathing, Lomura watched a variety show... 6:30 7 Landscape with Flatiron read by Adam Sims 6:56 8 As usual, Junko thought about Jack London’s ‘To build a Fire’. 7:11 9 Junko came to this Ibaraki town in May... 6:16 10 Walking on the beach one evening a few days later... 3:28 11 The flames finally found their way to the biggest log... 7:20 12 The bonfire was nearing its end. 6:57 Total time on CD 1: 73:11 2 NA443212 after the quake booklet 17/10/06 2:34 pm Page 3 CD 2 1 All God’s Children Can Dance read by Rupert Degas 4:34 2 Yoshiya’s mother was 43, but she didn’t look more than 35. 5:45 3 When Yoshiya turned 17, his mother revealed the secret... 6:39 4 The man boarded the Chiyoda Line train to Abiko. 4:35 5 The train was almost out of Tokyo and just a station or two.. -

Literature's Postmodern Condition

Literature’s Postmodern Condition: Representing the Postmodern in the Translated Novel Name: Deirdre Flynn Award: PhD Institution: Mary Immaculate College, University of Limerick Supervisor: Dr Eugene O’Brien Submitted to the University of Limerick, date Literature’s Postmodern Condition: Representing the Postmodern in the Translated Novel ii Declaration I hereby declare that this thesis represents my own work and has not been submitted, in whole or part, by me or another person, for the purpose of obtaining any other qualification. Signed: ___________________ Date: iii Dedication To Kafka Tamura for sending me into this metaphysical storm iv Acknowledgements I would like to thank my supervisor, Dr Eugene O’Brien, for all his help, guidance and support; my family for their patience; and Shane Keogh for everything. v Portions of this thesis have been disseminated at the following conferences and in the following publications: Conferences ‘The Postmodern Protagonist: Publicly Positioned and Privately Prejudiced’ Public/Private Conference, Mary Immaculate College, May 2011. ‘If Modern Life is Rubbish, What is Postmodern Life?’ The Contemporary: An International Conference of Literature and the Arts, June 24 – 26, 2011, Nayang University, Singapore. ‘When Work Doesn’t Work’ RePresentations of Working Life Conference, November 18-20, 2011, Erlangen University, Germany. ‘Adventures in the Postmodern Wonderland’ Future Adventures in Wonderland: The Aftermath of Alice Conference, December 1, 2011, HIC Dragonnes, Manchester. ‘Postmodern Literature: Murakami’s International Chronicle’ What Happens Now: 21st Century Writing in English, July 16-18, 2012, Lincoln University. ‘Positioning the Postmodern Female’ Otherness in philosophy, theory and art practice, November 23, 2012, The Centre vi for Otherness, Limerick. -

Special Article 2

Special Article 2 By Mukesh Williams Author Mukesh Williams Murakami’s fictional world is a world of elegiac beauty filled with mystical romance, fabulous intrigues and steamy sex where his stories race towards a dénouement hard to fathom. Within the wistful experience of this world people disappear and reappear recounting strange tales of mutants, alternate reality, cults, crime and loneliness. Occasionally with a sleight of hand Murakami switches the world that his characters inhabit and absolves them of any moral or legal responsibility. Much to the dislike of Japanese traditionalists, Murakami’s fiction has gained wide readership in both Japan and the West, perhaps making him the new cultural face of Japan and a possible choice for the Nobel Prize in Literature. Though some might dismiss him as a pop artist, eccentric lone wolf, or Americanophile, he represents a new Japanese sensibility, a writer who fuses Western and Japanese culture and aesthetics with unique Japanese responses. In this sense he is the first Japanese writer with a postmodernist perspective rooted within the Japanese cultural ethos, outdoing Junichiro Tanizaki’s modernist viewpoint. Impact of the Sixties composers such as Bach, Beethoven, Chopin, Debussy, Handel, Mozart, Schubert and Wagner, and jazz artists like Nat King Cole, Murakami’s fiction also returns to the powerful American era of the Bing Crosby and Frank Sinatra. Interestingly Murakami has rejected 1960s and its impact upon Japan in later decades. The literature, much of Japanese literature but likes to read a few modern Japanese attitudes, and music of the Sixties are just waiting to be told in writers such as Ryu Murakami and Banana Yoshimoto. -

Natsume Sōseki and Modern Japanese Literature by Marvin Marcus

Asia: Biographies and Personal Stories, Part II Natsume Sōseki and Modern Japanese Literature By Marvin Marcus atsume Sōseki (1867–1916) is one of a The Meiji mission was to create a mod- handful of individuals who both sym- ern nation with state-of-the-art education, bolized Japan’s emergence as a mod- technology, media, and urban development. Nern nation and helped mold an understand- Tokyo—the erstwhile Tokugawa shogunal ing of the modern condition through his life’s capital—would be a showcase of Japanese mo- work. Literature was Sōseki’s creative vehicle, dernity and the center of the nation’s cultural but his significance in the context of a broader and intellectual life. Western know-how would national identity is greater than the sum of his be privileged, together with a new social and individual works. In short, his stature is akin political agenda that recognized individualism, to that of Mark Twain, a consensus American autonomy, and equality. icon. Yet these modern developments had to Born at the end of Japan’s final shogunal contend with a significant conservative agen- epoch, the Tokugawa period (1603–1868), da adopted by the powerful Meiji oligarchs— Sōseki died several years following the death themselves erstwhile samurai. Cognizant of the of the Meiji Emperor. His life span essential- need to leverage Tokugawa nativist teachings ly overlaps the seminal Meiji period in Japan’s as a hedge against Western hegemony, they re- history (1868–1912), and his literature has stored the emperor as a national sovereign, pa- long been regarded as having captured the so- triarch, and Shinto divinity.