D Docto Or of I L Phil in Law Losop

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Post-Medieval Rural Landscape, C AD 1500–2000 by Anne Dodd and Trevor Rowley

THE THAMES THROUGH TIME The Archaeology of the Gravel Terraces of the Upper and Middle Thames: The Thames Valley in the Medieval and Post-Medieval Periods AD 1000–2000 The Post-Medieval Rural Landscape AD 1500–2000 THE THAMES THROUGH TIME The Archaeology of the Gravel Terraces of the Upper and Middle Thames: The Thames Valley in the Medieval and Post-Medieval Periods AD 1000-2000 The post-medieval rural landscape, c AD 1500–2000 By Anne Dodd and Trevor Rowley INTRODUCTION Compared with previous periods, the study of the post-medieval rural landscape of the Thames Valley has received relatively little attention from archaeologists. Despite the increasing level of fieldwork and excavation across the region, there has been comparatively little synthesis, and the discourse remains tied to historical sources dominated by the Victoria County History series, the Agrarian History of England and Wales volumes, and more recently by the Historic County Atlases (see below). Nonetheless, the Thames Valley has a rich and distinctive regional character that developed tremendously from 1500 onwards. This chapter delves into these past 500 years to review the evidence for settlement and farming. It focusses on how the dominant medieval pattern of villages and open-field agriculture continued initially from the medieval period, through the dramatic changes brought about by Parliamentary enclosure and the Agricultural Revolution, and into the 20th century which witnessed new pressures from expanding urban centres, infrastructure and technology. THE PERIOD 1500–1650 by Anne Dodd Farmers As we have seen above, the late medieval period was one of adjustment to a new reality. -

Lancaster Plain, C. 1730-1960

Agricultural Resources of Pennsylvania, c. 1700-1960 Lancaster Plain, c. 1730-1960 2 Lancaster Plain, 1730-1960 Table of Contents Lancaster Plain Historic Agricultural Region, c. 1730-1960....................................................... 4 Location ..................................................................................................................................... 9 Climate, Soils, and Topography................................................................................................ 10 Historical Farming Systems ...................................................................................................... 12 Diverse Production for Diverse Uses, c. 1730 to about 1780 ............................................... 12 Products, c 1730-1780 ...................................................................................................... 12 Labor and Land Tenure, 1730-1780 ................................................................................. 16 Buildings and Landscapes, 1730-1780 ............................................................................. 17 Farm House, 1730-1780................................................................................................ 17 Ancillary houses, 1730-1780 ........................................................................................ 19 Barns, 1730-1780 .......................................................................................................... 19 Outbuildings, c 1730-1780: ......................................................................................... -

Heritage Barns Statewide Survey and Physical Needs Assessment

Heritage Barns Statewide Survey and Physical Needs Assessment Washington state Heritage Barn Preservation Advisory Committee WASHINGTON STATE HERITAGE BARN SURVEY AND PHYSICAL NEEDS ASSESSMENT 1 This report commissioned by the Washington state Department of Archaeology and Historic Preservation for the Washington state Heritage Barn Preservation Advisory Committee. Published June 30, 2008 Cover image of a calvary horse barn Fort Spokane. Source Artifacts Consulting, Inc., graphic design by Rusty George Creative. 2 WASHINGTON STATE DEPARTMENT OF ARCHAEOLOGY AND HISTORIC PRESERVATION Contributors The authors of this report wish to extend our deepest thanks to the following persons, departments, govern- ment and nonprofit entities that worked so hard to provide information and facilitate research and study. With- out their help this project would not have been possible. Our thanks to the: Washington State Heritage Barn Preservation Advisory Committee members Dr. Allyson Brooks, Ph.D. (ex-officio), Jerri Honeyford, Chair, Brian Rich, Jack Williams, Janet Lucas, Jeanne Youngquist, Larry Cooke, Paula Holloway, Teddie Mae Charlton, and Tom Bassett; Washington State Department of Archaeology and Historic Preservation, Allyson Brooks, Ph.D., State Historic Preservation Officer for keeping us all focused and on track amidst so many exciting tangents and her review of the draft, Greg Griffith, Deputy State Historic Preservation Officer, Michael Houser, Architectural Historian for the tremendous effort in transferring Heritage Barn register data -

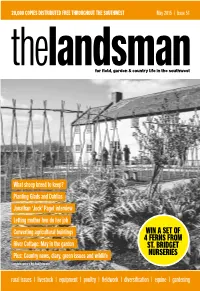

Win a Set of 4 Ferns from St. Bridget Nurseries

20,000 COPIES DISTRIBUTED FREE THROUGHOUT THE SOUTHWEST May 2015 | Issue 51 What sheep breed to keep? Planting Glads and Dahlias Jonathan ‘Jock’ Paget interview Letting mother hen do her job Converting agricultural buildings WIN A SET OF 4 FERNS FROM River Cottage: May in the garden ST. BRIDGET Plus: Country news, diary, green issues and wildlife NURSERIES Cover photo courtesy of Nick Hook Photography rural issues | livestock | equipment | poultry | fieldwork | diversification | equine | gardening 1 NATURAL, SUSTAINABLE FENCING AND GARDEN PRODUCTS We offer a full range of willow hurdles, trellis and arches. Standard sizes from £28.30 or bespoke sizes available on request. In-situ service also available - we will come and weave your fencing in situ, please telephone for further details and a quotation. Delivery available, please ring for charges. Hanging chairs or pod chairs also available. Please check our website for images. Come and visit us and see what’s on offer – a warm welcome awaits you. ■ Enjoy a walk on the Somerset Levels and see the willow growing in the withy beds. ■ Learn about the willow industry and view the rare selection of basket ware in our museum. ■ Browse through our basket shop and craft studios and enjoy refreshments at The Lemon Tree Coffee House. ■ Admission is free but tours of the basket workshops are available Monday to Friday at 11am and 2.30pm at £3.00 per person ■ We are open from 9.30am to 5.00pm Monday to Saturday (closed on Sundays). PH Coate & Son Ltd, The Willows & Wetlands Visitor Centre, Meare Green Court, Stoke St Gregory, Taunton, TA3 6HY Tel: 01823 490249 www.coatesenglishwillow.co.uk 2 inside this issue Competition 5 Win one of three sets of four ferns from St. -

Pennsylvania Folklife Vol. 15, No. 4 Constantine Kermes

Ursinus College Digital Commons @ Ursinus College Pennsylvania Folklife Magazine Pennsylvania Folklife Society Collection Summer 1966 Pennsylvania Folklife Vol. 15, No. 4 Constantine Kermes Earl F. Robacker Ada Robacker Henry Glassie Don Yoder See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ursinus.edu/pafolklifemag Part of the American Art and Architecture Commons, American Material Culture Commons, Christian Denominations and Sects Commons, Cultural History Commons, Ethnic Studies Commons, Fiber, Textile, and Weaving Arts Commons, Folklore Commons, Genealogy Commons, German Language and Literature Commons, Historic Preservation and Conservation Commons, History of Religion Commons, Linguistics Commons, and the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits oy u. Recommended Citation Kermes, Constantine; Robacker, Earl F.; Robacker, Ada; Glassie, Henry; Yoder, Don; Barrick, Mac E.; Dieffenbach, Victor C.; and Power, Tyrone, "Pennsylvania Folklife Vol. 15, No. 4" (1966). Pennsylvania Folklife Magazine. 25. https://digitalcommons.ursinus.edu/pafolklifemag/25 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Pennsylvania Folklife Society Collection at Digital Commons @ Ursinus College. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pennsylvania Folklife Magazine by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Ursinus College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Authors Constantine Kermes, Earl F. Robacker, Ada Robacker, Henry Glassie, Don Yoder, Mac E. Barrick, Victor C. Dieffenbach, and Tyrone Power This book is available at Digital Commons @ Ursinus College: https://digitalcommons.ursinus.edu/pafolklifemag/25 AMISH PENNSYLVANIANS Sall erkraut-ma /ling til e Old TV ay-From H . L. Fischer, "'S A It Marik-Haw" (York, 1879). -

Historic Farmsteads

7.0 Key Building Types: Animals and Animal Products 7.1 CATTLE HOUSING • Interior stalling and feeding arrangements. Cows were usually tethered in pairs with low partitions of wood, 7.1.1 NATIONAL OVERVIEW (Figure 27) stone, slate and, later, cast iron between them. As the There are great regional differences in the management breeding of stock improved and cows became larger, of cattle and the buildings that house them.This extends the space for the animals in the older buildings to how they are described in different parts of the became limited and an indication of the date of a cow country: for example,‘shippon’ in much of the South house can be the length of the stalls or the width of West;‘byre’ in northern England;‘hovel’ in central the building. Feeding arrangements can survive in the England. Stalls, drains and muck passages have also been form of hayracks, water bowls and mangers for feed. given their own local vocabulary. • Variations in internal planning, cattle being stalled along or across the main axis of the building and facing a Evidence for cattle housing is very rare before the wall or partition.They were fed either from behind or 18th century, and in many areas uncommon before the from a feeding passage, these often being connected 19th century.The agricultural improvements of the 18th to fodder rooms from the late 18th century. century emphasised the importance of farmyard manure in maintaining the fertility of the soil. It was also In the following descriptions of buildings for cattle the recognised that cattle fattened better and were more wide variety in the means of providing accommodation productive in milk if housed in strawed-down yards and for cattle, both over time and regionally, can be seen . -

Thematic Survey of Historic Barns in Northeast Oklahoma

Thematic Survey of Historic Barns in Northeast Oklahoma Adair, Cherokee, Creek, Craig, Delaware, Mayes, McIntosh, Muskogee, Nowata, Okfuskee, Okmulgee, Osage, Ottawa, Pawnee, Rogers, Sequoyah, Tulsa, Wagoner, and Washington Counties Prepared for: OKLAHOMA HISTORICAL SOCIETY State Historic Preservation Office Oklahoma History Center 800 Nazih Zuhdi Drive Oklahoma City, Oklahoma 73105-7914 Prepared by: Brad A. Bays, Ph.D. Department of Geography 337 Murray Hall Oklahoma State University Stillwater, Oklahoma 74078-4073 2 Acknowledgement of Support The activity that is the subject of this survey has been financed in part with Federal funds from the National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. However, the contents and opinions do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of the Interior. Nondiscrimination Statement This program receives Federal financial assistance for identification and protection of historic properties. Under Title VI of the Civil rights Act of 1964, Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, and the Age Discrimination Act of 1975, as amended, the U.S. Department of the Interior prohibits discrimination on the basis of race, color, national origin, disability, or age in its federally assisted programs. If you believe you have been discriminated against in any program, activity, or facility as described above, or if you desire further information, please write to: Office of Equal Opportunity National Park Service 1849 C Street, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20240 3 CONTENTS 4 5 6 I. ABSTRACT Under contract to the Oklahoma State Historic Preservation Office, Brad A. Bays of Oklahoma State University, Stillwater, conducted the Survey of Historic Barns in Northeastern Oklahoma (OK/SHPO Management Region Three) during the fiscal year 2012- 2013. -

The Pennsylvania Dutch in the 21St Century

Plain, Fancy and Fancy-Plain: The Pennsylvania Dutch in the 21st Century Rian Linda Larkin Faculty Advisor: Alex Harris Center for Documentary Studies December 2017 This project was submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Graduate Liberal Studies Program in the Graduate School of Duke University. Copyright by Rian Linda Larkin 2017 Abstract In 1681, William Penn traveled to Europe’s Rhineland-Palatinate and invited Anabaptist and Protestant groups to live and worship freely in Pennsylvania. Over the next century, 111,000 German- speaking men and women sailed to America, many settling in southeastern Pennsylvania.1 During this period, English-speaking residents began to use the term, “Pennsylvania Dutch” to describe the new settlers who spoke Deitsch or Deutsch (German). Today, the term Pennsylvania Dutch conjures visions of bonnets, beards, suspenders and horse- drawn buggies. However, this imagery only applies to the Old Order Anabaptist sects, which constitute less than half of Pennsylvania’s total PA Dutch population.2 3 Therefore, this project will examine and document four Pennsylvania Dutch communities in order to present a more accurate cultural portrait and contextualize the Pennsylvania Dutch populace in the 21st century, from anachronistic traditionalists to groups that have fully integrated into modern society. The project documents the following religious communities: the Old Order Amish, Horning Mennonites, Moravians and Lutherans of southeastern Pennsylvania. Each section includes a historical overview, an interview with a community member and photographs taken on-location. I conclude that church-imposed restrictions and geographical location shaped each group’s distinctive character and impacted how the groups evolved in the modern world. -

Area West Committee

Area West Committee Wednesday 17th October 2012 5.30 pm Merriott Village Hall, 51 Broadway, Merriott, Somerset TA16 5QH (location plan overleaf - disabled access is available at this meeting venue) The public and press are welcome to attend. Please note: Planning applications will be considered no earlier than 6.30 pm If you would like any further information on the items to be discussed, please ring the Agenda Co-ordinator, Jo Morris on Yeovil (01935) 462462 email: [email protected] This Agenda was issued on Monday, 8th October 2012 Ian Clarke, Assistant Director (Legal & Corporate Services) This information is also available on our website: www.southsomerset.gov.uk AW Area West Membership Chairman: Angie Singleton Vice-Chairman: Paul Maxwell Michael Best Jenny Kenton Kim Turner David Bulmer Nigel Mermagen Andrew Turpin John Dyke Sue Osborne Linda Vijeh Carol Goodall Ric Pallister Martin Wale Brennie Halse Ros Roderigo Somerset County Council Representatives Somerset County Councillors (who are not already elected District Councillors for the area) are invited to attend Area Committee meetings and participate in the debate on any item on the Agenda. However, it must be noted that they are not members of the committee and cannot vote in relation to any item on the agenda. The following County Councillors are invited to attend the meeting:- Councillor Cathy Bakewell and Councillor Jill Shortland. South Somerset District Council – Corporate Aims Our key aims are: (all equal) • Jobs – We want a strong economy which has low unemployment and thriving businesses • Environment – We want an attractive environment to live in with increased recycling and lower energy use • Homes – We want decent housing for our residents that matches their income • Health and Communities – We want communities that are healthy, self-reliant and have individuals who are willing to help each other Scrutiny Procedure Rules Please note that decisions taken by Area Committees may be "called in" for scrutiny by the Council's Scrutiny Committee prior to implementation. -

Wiltshire Farm Foods

Wiltshire Farm Foods your photographs. It would be handy though if BONAU RAFFLE you wrote your name and address on the back of the photo (in pencil) or you attached one of The results of our Summer draw can be found those ‘post-it-notes’. on page 26 Welcome to edition No 54 of The Bônau PWLL RESIDENTS & The local police rely on Cabbage Patch. We have put a lot of effort into TENANTS us, the public to come forward and provide preparing this edition for you and we hope you them with information so they can provide a "Poets have been mysteriously enjoy it. It has all the usual features plus, ASSOCIATION better service. It also keeps them in the loop of silent on the subject of cheese" hopefully, some you will find educating or The Pwll Residents what is really going on in our community. You - G. K. Chesterton (1874 - 1936) amusing. Enjoy. the magazine. Thanks. can contact them in several ways, all are Association meet @ 6:30 pm on the last confidential, and each will be investigated. You Monday of every month in the vestry of can notify them either by telephone, e-mail, Bethlehem Chapel. THANK YOU TO OUR SPONSORS Bobby Box etc. as follows: - PCSO 8005 Eira Do please go along as everyone is welcome to Jones telephone number 101 or e-mail We would like to welcome our new sponsors express their views and thoughts on what they [email protected] or at our PWLL NEIGHBOURHOOD WATCH & to the magazine and hope that our association think should be improved in the village. -

Kent Farmsteads Guidance

KENT FARMSTEADS GUIDANCE PART 7 GLOSSARY THIS COMPRISES PART 7 OF THE KENT FARMSTEADS GUIDANCE Traditional farmstead groups and their buildings are assets which make a of area guidance and for those with an interest in the county’s landscapes and positive contribution to local character. Many are no longer in agricultural historic buildings. The guidance is presented under the headings of: Historical use but will continue, through a diversity of uses, to make an important Development, Landscape and Settlement, Farmstead and Building Types and contribution to the rural economy and communities. The purpose of this Materials and Detail. guidance is to help achieve the sustainable development of farmsteads, and their conservation and enhancement. It can also be used by those with an PART 4 CHARACTER AREA STATEMENTS interest in the history and character of the county’s landscape and historic These provide summaries, under the same headings and for the same purpose, buildings, and the character of individual places. for the North Kent Plain and Thames Estuary, North Kent Downs, Wealden Greensand, Low Weald, High Weald and Romney Marsh. PART 1 FARMSTEADS ASSESSMENT FRAMEWORK This sets out the aims and purpose of the Kent Farmsteads Guidance and is PART 5 KENT FARMSTEADS DESIGN GUIDANCE divided into two sections: This provides illustrated guidance on design and new build, based on the 1. a Site Assessment Framework which will help applicants identify the range of historic farmstead types. It is intended to help applicants who are then capacity for change and any issues at the pre-application stage in the considering how to achieve successful design, including new-build where it is planning process, and then move on to prepare the details of a scheme. -

Haselton Barn Historic Structures Report

Historic Structures Report Benson’s Property Town of Hudson, New Hampshire May 22, 2003 – 100% Submittal The Haselton Barn Historic Structures Report Benson’s Property Town of Hudson, New Hampshire May 22, 2003 – 100% Submittal The Haselton Barn 27 Bush Hill Road Hudson, New Hampshire Principal Investigator Arron J. Sturgis Preservation Timber Framing Inc. PO Box 29 Eliot, Maine 03903 Architectural Investigator Linda Pate Preservation Timber Framing Inc. Architectural Documentation and Photography John Butler PO Box 593 10 Monument Square Hollis, NH 03049 Historical Architect S. Elizabeth Sasser, AIA 106 Horace Greeley Road Amherst, NH 03031 Benson’s Property Historic Structures Report Town of Hudson, New Hampshire Haselton Barn May 22, 2003 – 100% Submittal Table of Contents List of Figures and Credits 4 Executive Summary 5 Purpose of the Report 5 Research Methodology 5 Significance 6 Integrity 6 Major Issues Identified in the Scope of Work 6 Interim Treatment Recommendations 6 Ultimate Treatment Recommendations 6 Recommendations for Additional Research 7 Acknowledgments 7 Introduction 8 What is a Historic Structure Report? 8 Preservation Standards and Guidelines 8 Part 1: Development and Use 10 Historical Background and Context 10 Historic Hudson: 1761-1910 10 Interstate Fruit Farm: 1910-1924 11 Benson’s Wild Animal Farm: 1924-1943 12 Lapham Era: 1944-1976 12 Provencher Period: 1979-1987 12 New Hampshire Department of Transportation: 1992-2002 13 Architectural Description 15 Part 2: Treatment and Use 20 Character-Defining Features and