UC Berkeley Recent Work

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Meeting Minutes

BOARD OF SUPERVISORS CITY AND COUNTY OF SAN FRANCISCO MEETING MINUTES Tuesday, December 8, 2020 - 2:00 PM Held via Videoconference (remote public access provided via teleconference) www.sfgovtv.org Regular Meeting NORMAN YEE, PRESIDENT SANDRA LEE FEWER, MATT HANEY, RAFAEL MANDELMAN, GORDON MAR, AARON PESKIN, DEAN PRESTON, HILLARY RONEN, AHSHA SAFAI, CATHERINE STEFANI, SHAMANN WALTON Angela Calvillo, Clerk of the Board BOARD COMMITTEES Committee Membership Meeting Days Budget and Appropriations Committee Wednesday Supervisors 1:00 PM Budget and Finance Committee Wednesday Supervisors Fewer, Walton, Mandelman 10:30 AM Government Audit and Oversight Committee 1st and 3rd Thursday Supervisors Mar, Peskin, Haney 10:00 AM Joint City, School District, and City College Select Committee 2nd Friday Supervisors Haney, Fewer, Mar (Alt), Commissioners Moliga, Collins, Cook (Alt), 10:00 AM Trustees Randolph, Williams, Selby (Alt) Land Use and Transportation Committee Monday Supervisors Preston, Safai, Peskin 1:30 PM Public Safety and Neighborhood Services Committee 2nd and 4th Thursday Supervisors Mandelman, Stefani, Walton 10:00 AM Rules Committee Monday Supervisors Ronen, Stefani, Mar 10:00 AM First-named Supervisor is Chair, Second-named Supervisor is Vice-Chair of the Committee. Volume 115 Number 46 Board of Supervisors Meeting Minutes 12/8/2020 Members Present: Sandra Lee Fewer, Matt Haney, Rafael Mandelman, Gordon Mar, Aaron Peskin, Dean Preston, Hillary Ronen, Ahsha Safai, Catherine Stefani, Shamann Walton, and Norman Yee The Board of Supervisors of the City and County of San Francisco met in regular session through videoconferencing, and provided public comment through teleconferencing, on Tuesday, December 8, 2020, with President Norman Yee presiding. -

VTA Daily News Coverage for Thursday, October 24 and Friday, October 25, 2019

From: VTA Board Secretary <[email protected]> Sent: Monday, October 28, 2019 10:09 AM To: VTA Board Secretary <[email protected]> Subject: From VTA: Oct 24-25, 2019 Medial Clips VTA Daily News Coverage for Thursday, October 24 and Friday, October 25, 2019 1. Bay Area companies and community groups push for $16B transportation investment (San Jose Spotlight) 2. Will $100 billion transportation mega-measure be put at risk by SF supervisors? (San Francisco Chronicle) Bay Area companies and community groups push for $16B transportation investment (San Jose Spotlight) A group of 32 Bay Area organizations, from private tech companies to community groups, on Wednesday urged local lawmakers to take big, new strides to invest in transportation throughout the region. In a letter, signed by Alphabet-owned Waymo, San Francisco-based ridesharing and scooter companies Lyft and Lime alongside a slew of Bay Area bicycle coalitions, asked lawmakers to prioritize $16.32 billion in transportation initiatives in the coming decades. The group also suggested area leaders consider a new region-wide transportation tax measure to get those priory improvements moving. That ask comes amid chatter around the nine-county Bay Area about potential new funding initiatives for transportation in the coming years, said Emma Shlaes, policy director for the Silicon Valley Bicycle Coalition. “We were just, in general, putting forward our thoughts for the next few decades so we don’t get left behind in the conversations that are going on at the regional level,” she said. “Sometimes the conversation is dominated by transit cars and highways.” While the letter could be interpreted as an open call to Bay Area leaders making decisions about transit and transportation, the group also specifically sent the framework to agencies tasked with battling traffic congestion, including the VTA, and to the mayors of major cities throughout the region, Shlaes said. -

FALL 2008 Postcard Lambasts Welch CVIA Fights City Hall for It Arrived in the Mail on July 24

COLE VALLEY IMPROVEMENT ASSOCIATION CVIAVolume XXI SERVING ALL RESIDENTSNEWS OF THE GREATER HAIGHT ASHBURY FALL 2008 Postcard Lambasts Welch CVIA Fights City Hall for It arrived in the mail on July 24. A large color postcard with Review of 850 Street Boxes a picture of Calvin Welch, looking particularly aggravated and a plea to Haight residents to “Get Involved.” Welch is leading the The Situation campaign to thwart the mixed-use project on the corner of Haight With breathtaking audacity, AT&T applied for and received and Stanyan, which includes a Whole Foods on the ground floor, permission from the Planning Department to place up to 850 metal 62 residential units above and a 172 car garage below. Beside the “Lightspeed” cabinets on public sidewalks around the city, and photo (now known as Calvin Agonistes) was an news clipping of enlarge some of their existing electrical boxes. Installation has his earlier fight to stop the same property owner, John Brennan, already begun. from renting the ground floor of another Haight property to Thrifty The new cabinets are 4 feet high, 4 feet 2 inches wide, and 26 Drugs. The return address on the card was Brennan’s. inches deep. They would be installed within 150 feet of existing Oddly, this long war between Welch and Brennan, as divisive electrical boxes, as it’s been for the neighborhood merchants, who have been forced some of which to choose sides, has generally been resolved satisfactorily. Although would be en- the Haight lost the chance for a drugstore, and a trendy clothing/ larged to be 4 feet housewares vendor, it did get an excellent Goodwill store and a 10 inches wide Wells Fargo Bank. -

1 Chinatown Subway: Name It After a Truly Great Hero, Not Rose Pak

1875 L Street NW, Suite 400, Washington DC, 20006 Office: (202) 697-3858 Email: [email protected] Chinatown Subway: Name it After a Truly Great Hero, not Rose Pak Dear SFMTA Board Members, Congratulations on the new subway stop in Chinatown. That is a huge accomplishment, for which Rose Pak may deserve some credit, though not the high honor of having her name immortalized on a San Francisco landmark. Naming a geographic feature after an individual deserves true greatness, and we can think of no better person than Liu Xiaobo, a philosopher, poet, and human rights activist who won a Nobel Peace prize. Alternatively, we would suggest naming the subway stop as simply Chinatown, which represents all the great diversity of the neighborhood over the many decades of its flourishing. Rose Pak, unfortunately, has a history that makes her inappropriate as a true hero of the Chinese people, or of San Francisco. China uses influence tactics, especially through its United Front Work Department, to compromise U.S. democracy, and democracies around the world. The most horrendous examples of this are in East Turkistan, where 1-3 million minorities have been locked up due to their beliefs, in Tibet, where Buddhist monasteries are torn down, against the Falun Gong, who are subject to forced organ transplants, and in Hong Kong, where the hopes of over a million people who have marched to demand freedom and democracy from the Chinese Communist Party are being suppressed through police brutality. As discussed below, this is not the right time to honor someone who has been closely associated with China's dictatorship. -

FILE NO. 130612 Petitions and Communications Received From

FILE NO. 130612 Petitions and Communications received from June 3, 2013, through June 10, 2013, for reference by the President to Committee considering related matters, or to be ordered filed by the Clerk on June 18, 2013. Personal information that is provided in communications to the Board of Supervisors is subject to disclosure under the California Public Records Act and the San Francisco Sunshine Ordinance. Personal information will not be redacted. From Superior Court of California, submitting 2012-2013 Civil Grand Jury report entitled, “Are the Wheels Moving Forward?” Copy: Each Supervisor, Clerk of the Board, Legislative Deputy, Government Audit & Oversight Committee Clerk, Legislation Clerk. (1) *From Office of Budget and Legislative Analyst, submitting Housing Authority performance audit. (2) From concerned citizens, regarding fiber broadband. 3 letters. Copy: Each Supervisor. (3) From Library Users Association, regarding the Public Library evening hours. Copy: Each Supervisor, Clerk of the Board. (4) From A. Alberto Castillio Abello, regarding proposed reduction to health services for FYs 2013-2014 and 2014-2015. File No. 130595. Copy: Each Supervisor. (5) From concerned citizens, regarding Pier 70 Waterfront Site. File No. 130495. 3 letters. Copy: Each Supervisor, Budget & Finance Committee Clerk. (6) From concerned citizens, regarding Vibrant Castro Neighborhood Alliance petition. 11 letters. Copy: Each Supervisor. (7) From Randolph Badler, Ph.D., regarding construction parking permits. Copy: Each Supervisor, Legislative Aides. (8) From Sid Castro, regarding sale of taxi medallions. Copy: Each Supervisor. (9) From Marvis J. Phillips, regarding liquor license transfer for 1552 Polk Street. File No. 130307. Copy: Each Supervisor, Neighborhood Services & Safety Committee Clerk. -

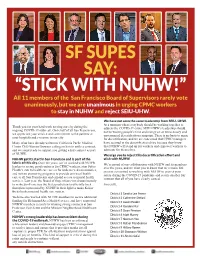

SF BOS Letter to CPMC Members

SF SUPES SAY: “STICK WITH NUHW!” All 11 members of the San Francisco Board of Supervisors rarely vote unanimously, but we are unanimous in urging CPMC workers to stay in NUHW and reject SEIU-UHW. We have not seen the same leadership from SEIU–UHW. At a moment when everybody should be working together to Thank you for your hard work serving our city during the address the COVID-19 crisis, SEIU-UHW’s leadership should ongoing COVID-19 outbreak. On behalf of all San Franciscans, not be wasting people’s time and energy on an unnecessary and we appreciate your service and commitment to the patients at unwarranted decertification campaign. There is no basis to argue your hospitals and everyone in our city. for decertification, and we are concerned that CPMC managers Many of us have already written to California Pacfic Medical have assisted in the decertification drive because they know Center CEO Warren Browner calling on him to settle a contract, that NUHW will stand up for workers and empower workers to and we stand ready to support you getting a fair contract as part advocate for themselves. of NUHW. We urge you to reject this decertification effort and NUHW got its start in San Francisco and is part of the stick with NUHW. fabric of this city. Over the years, we’ve worked with NUHW We’re proud of our collaboration with NUHW and its members leaders to secure good contracts for CPMC workers, stop Sutter over the years, and we want you to know that we remain 100 Health’s cuts to health care access for underserved communities, percent committed to working with NUHW to protect your and initiate pioneering programs to provide universal health safety during the COVID-19 pandemic and secure another fair care to all San Franciscans and expand access to mental health contract that all of you have clearly earned. -

Contacting Your Legislators Prepared by the Government Information Center of the San Francisco Public Library - (415) 557-4500

Contacting Your Legislators Prepared by the Government Information Center of the San Francisco Public Library - (415) 557-4500 City of San Francisco Legislators Mayor London Breed Board of Supervisors voice (415) 554-6141 voice (415) 554-5184 fax (415) 554-6160 fax (415) 554-5163 1 Dr. Carlton B. Goodlett Place, Room 200 1 Dr. Carlton B. Goodlett Place, Room 244 San Francisco, CA 94102-4689 San Francisco, CA 94102-4689 [email protected] [email protected] Members of the San Francisco Board of Supervisors Sandra Lee Fewer Catherine Stefani Aaron Peskin District 1 District 2 District 3 voice (415) 554-7410 fax voice (415) 554-7752 fax (415) voice (415) 554-7450 fax (415) 554-7415 554-7843 (415) 554-7454 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Gordon Mar Vallie Brown Matt Haney District 4 District 5 District 6 voice (415) 554-7460 voice (415) 554-7630 voice (415) 554-7970 fax (415) 554-7432 fax (415) 554-7634 fax (415) 554-7974 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Norman Yee * Rafael Mandelman Hillary Ronen District 7 District 8 District 9 voice (415) 554-6516 voice (415) 554-6968 voice (415) 554-5144 fax (415) 554-6546 fax (415) 554-6909 fax (415) 554-6255 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Shamann Walton Ahsha Safaí District 10 District 11 voice (415) 554-7670 voice (415) 554-6975 fax (415) 554-7674 fax (415) 554-6979 [email protected] [email protected] *Board President California State Legislator Members from San Francisco Senate Scott Wiener (D) District 11 voice (916) 651-4011 voice (415) 557-1300 Capitol Office 455 Golden Gate Avenue, Suite State Capitol, Room 4066 14800 Sacramento, CA 95814-4900 San Francisco, CA 94102 [email protected] Assembly David Chiu (D) District 17 Philip Y. -

72 Hour Notice

San Francisco Democratic County Central Committee Special Meeting Wednesday, August 5, 2020 6:30pm Virtual Meeting via Zoom Video Call (More details to be provided) 72 Hour Meeting Agenda ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 1. Call to Order and Roll Call Call to Order by Chair, David Campos. Roll Call of Members: John Avalos, Keith Baraka, Gloria Berry, David Campos, Queena Chen, Bevan Dufty, Peter Gallotta, Matt Haney, Anabel Ibáñez, Jane Kim, Leah LaCroix, Janice Li, Suzy Loftus, Li Miao Lovett, Honey Mahogany, Rafael Mandelman, Gordon Mar, Faauuga Moliga, Carolina Morales, Mano Raju, Hillary Ronen, Amar Thomas, Nancy Tung, Shanell Williams. Ex-Officio Members: U.S. Senator Dianne Feinstein; Speaker of the House of Representatives Nancy Pelosi; U.S. House Representative Jackie Speier; Lieutenant Governor Eleni Kounalakis, State Treasurer Fiona Ma; Board of Equalization Member Malia Cohen, State Senator Scott Wiener; Assemblymember Phil Ting and Assemblymember David Chiu. 2. Approval of Meeting Agenda (Discussion and possible action) Discussion and possible action regarding the approval of this agenda. 3. Approval of July Meeting Minutes (Discussion and possible action) Approval of the minutes of the DCCC’s meeting of July 22, 2020 (minutes attached). 4. Interviews of Qualified Local Measures (https://sfelections.sfgov.org/measures) - Affordable Housing Authorization (Ordinance) - Sheriff Oversight (Charter Amendment) - Police Staffing -

Meeting Minutes

BOARD OF SUPERVISORS CITY AND COUNTY OF SAN FRANCISCO MEETING MINUTES Tuesday, June 11, 2019 - 2:00 PM Legislative Chamber, Room 250 City Hall, 1 Dr. Carlton B. Goodlett Place San Francisco, CA 94102-4689 Regular Meeting NORMAN YEE, PRESIDENT VALLIE BROWN, SANDRA LEE FEWER, MATT HANEY, RAFAEL MANDELMAN, GORDON MAR, AARON PESKIN, HILLARY RONEN, AHSHA SAFAI, CATHERINE STEFANI, SHAMANN WALTON Angela Calvillo, Clerk of the Board BOARD COMMITTEES Committee Membership Meeting Days Budget and Finance Committee Wednesday Supervisors Fewer, Stefani, Mandelman, Ronen, Yee 1:00 PM Budget and Finance Sub-Committee Wednesday Supervisors Fewer, Stefani, Mandelman 10:00 AM Government Audit and Oversight Committee 1st and 3rd Thursday Supervisors Mar, Brown, Peskin 10:00 AM Joint City, School District, and City College Select Committee 2nd Friday Supervisors Haney, Walton, Mar (Alt), Commissioners Cook, Collins, Moliga (Alt), 10:00 AM Trustees Randolph, Williams, Selby (Alt) Monday Land Use and Transportation Committee 1:30 PM Supervisors Peskin, Safai, Haney 2nd and 4th Thursday Public Safety and Neighborhood Services Committee 10:00 AM Supervisors Mandelman, Stefani, Walton Monday Rules Committee 10:00 AM Supervisors Ronen, Walton, Mar First-named Supervisor is Chair, Second-named Supervisor is Vice-Chair of the Committee. Volume 114 Number 19 Board of Supervisors Meeting Minutes 6/11/2019 Members Present: Vallie Brown, Sandra Lee Fewer, Matt Haney, Rafael Mandelman, Gordon Mar, Aaron Peskin, Hillary Ronen, Ahsha Safai, Catherine Stefani, Shamann Walton, and Norman Yee The Board of Supervisors of the City and County of San Francisco met in regular session on Tuesday, June 11, 2019, with President Norman Yee presiding. -

Inyong Pagpili. Inyong Lungsod

Lungsod at County ng San Francisco Pamplet ng Impormasyon para sa Botante Bumoto sa pamamagitan ng Koreo: Inyong Lungsod. Humiling bago o sa Oktubre 30 Bumoto sa City Hall: Inyong Pagpili. Oktubre 9 – Nobyembre 6 Eleksyon sa Nobyembre 6, 2018 Bumoto sa inyong Lugar ng Botohan: Nobyembre 6, Araw ng Eleksyon Para sa Halimbawang Balota para sa eleksyong ito, mangyaring tingnan ang bersiyong Ingles nitong pamplet, na ipinadala sa lahat ng nakarehistrong botante. Kung gusto ninyo ng isa pang kopya ng bersiyong Ingles nitong pamplet, mangyaring tumawag sa (415) 554-4310. Inilathala ng: Maaari din ninyong matingnan ang inyong Halimbawang Balota sa sfelections.org. Departamento ng mga Eleksyon Lungsod at County ng San Francisco Mga Importanteng Petsa Magbubukas ang City Hall Voting Center Martes, Oktubre 9 (Sentro ng Botohan sa City Hall) Huling araw para magparehistro upang makaboto Lunes, Oktubre 22 • Hindi umabot sa deadline? Bisitahin ang sfelections.org, “Rehistrasyon para sa mga Espesyal na Kalagayan” • Maaaring magparehistro at bumoto ang mga bagong mamamayan ng Estados Unidos sa City Hall hanggang sa Araw ng Eleksyon Pagboto sa weekend sa City Hall Voting Center Sabado at Linggo, Oktubre 27–28 Huling araw para humiling ng vote-by-mail (pagboto sa Martes, Oktubre 30 pamamagitan ng koreo) na balota Pagboto sa weekend sa City Hall Voting Center Sabado at Linggo, Nobyembre 3–4 Bukas ang mga Drop-off Station (Lugar na Sabado–Martes, Nobyembre 3–6 Paghuhulugan) ng Balota sa ilang pasukan ng City Hall Oras ng botohan sa Araw ng Eleksyon (lahat ng mga Martes, Nobyembre 6, lugar ng botohan at sa City Hall Voting Center) mula 7 a.m. -

A Wave Election in San Francisco

The taste of San Francisco Election Special The Tablehopper on the return of Greens p.12 Peskin’s ballot breakdown p.11 New & Notable: Peruvian-Japanese sensation p.13 Make room for animals p.20 Do not offer Michael Snyder a pumpkin latte p.19 Real Estate propositions p.22 MARINATIMES.COM CELEBRATING OUR 34TH YEAR VOLUME 34 ISSUE 10 OCTOBER 2018 Reynolds Rap Break out the ruby slippers and the flying monkeys With the millions San Francisco spends on homelessness, we should be living in the Land of Oz BY SUSAN DYER REYNOLDS Detail of Jogmaya Devi’s A holy man in the forest (Shiva as Lord of the Animals) is featured in the Asian Art hen i interviewed chris megison, Museum’s Painting Is My Everything exhibition. © JOGMAYA DEVI. PHOTOGRAPH © ASIAN ART MUSEUM the cofounder and CEO of Solutions for Change (“Meet the man who runs a home- Wless program with a 93 percent success rate,” Reynolds Spotlight on India’s everyday Mithila art Rap, Sept. 2018), he had harsh words for the way San Francisco handles its homeless crisis, includ- BY SHARON ANDERSON and goddesses, ornamented icons of of female-generated income where ing financially. “There shouldn’t be a single person fertility on the walls and floors of women found their creative voices left in that city who says it’s about more money,” he asian art museum pres- dwellings extending back for gener- through paint. Megison said. Yet, here we are, facing Proposition C on ents a vibrant, traditional arts ations. Born out of the everyday sto- “Painting Is My Everything shares the November ballot. -

New Asia Restaurant, Inc

CITY AND COUNTY OF SAN FRANCISCO LONDON N. BREED, MAYOR OFFICE OF SMALL BUSINESS REGINA DICK-ENDRIZZI, DIRECTOR Legacy Business Registry Staff Report HEARING DATE SEPTEMBER 23, 2019 NEW ASIA RESTAURANT, INC. Application No.: LBR-2016-17-063 Business Name: New Asia Restaurant, Inc. Business Address: 772 Pacific Avenue District: District 3 Applicant: Hon Keung So, Owner Nomination Date: January 20, 2017 Nominated By: Supervisor Aaron Peskin Staff Contact: Richard Kurylo [email protected] BUSINESS DESCRIPTION New Asia Restaurant was established in February 1987 by husband and wife Robert Yick and Shew Yick. The business is located at 772 Pacific Avenue in the Chinatown neighborhood. New Asia Restaurant has been in the same location since it was established. The Yick family has a rich history in the Chinatown community. In 1910, they founded Robert Yick Company, a family-operated business that manufactures custom stainless products. The company gained a reputation for fabricating stainless steel wok ranges. Robert Yick Company was located in Chinatown in the building presently occupied by New Asia Restaurant. In 1970, Robert Yick Sr. relocated the business to a larger plant on Bayshore Boulevard. It was in 1970 after the Robert Yick Company plant was relocated that Asia Garden Restaurant was opened by Robert Yick and managed by Miguel Yuen. In 1987, New Asia Restaurant opened in the space. New Asia Restaurant is an iconic business in Chinatown. It is one of the largest Chinese restaurants in the neighborhood with a seating capacity of 100 tables, which means they can host a banquet for 1,000 people in a single event.