187859223.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pru Nus Contains Many Species and Cultivars, Pru Nus Including Both Fruits and Woody Ornamentals

;J. N l\J d.000 A~ :J-6 '. AGRICULTURAL EXTENSION SERVICE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA • The genus Pru nus contains many species and cultivars, Pru nus including both fruits and woody ornamentals. The arboretum's Prunus maacki (Amur Cherry). This small tree has bright, emphasis is on the ornamental plants. brownish-yellow bark that flakes off in papery strips. It is par Prunus americana (American Plum). This small tree furnishes ticularly attractive in winter when the stems contrast with the fruits prized for making preserves and is also an ornamental. snow. The flowers and fruits are produced in drooping racemes In early May, the trees are covered with a "snowball" bloom similar to those of our native chokecherry. This plant is ex of white flowers. If these blooms escape the spring frosts, tremely hardy and well worth growing. there will be a crop of colorful fruits in the fall. The trees Prunus maritima (Beach Plum). This species is native to the sucker freely, and unless controlled, a thicket results. The A coastal plains from Maine to Virginia. It's a sprawling shrub merican Plum is excellent for conservation purposes, and the reaching a height of about 6 feet. It blooms early with small thickets are favorite refuges for birds and wildlife. white flowers. Our plants have shown varying degrees of die Prunus amygdalus (Almond). Several cultivars of almonds back and have been removed for this reason. including 'Halls' and 'Princess'-have been tested. Although Prunus 'Minnesota Purple.' This cultivar was named by the the plants survived and even flowered, each winter's dieback University of Minnesota in 1920. -

Conservation Plant Release Brochure for Catskill Dwarf Sand Cherry

A Conservation Plant Released by the Natural Resources Conservation Service Big Flats Plant Materials Center, Big Flats, New York Conservation Uses ‘Catskill’ Catskill is mainly used in shoreline and streambank stabilization practices and riparian buffer plantings, where Dwarf Sand Cherry low vegetation is preferred. Its growth habit makes it adapted to areas with ice floe problems. Prunus pumila var. depressa L. Due to its prostrate growth, it may become shaded out over time by taller vegetation. The fruits produced by Catskill are valuable for wildlife and is a very attractive plant and is used in ornamental landscaping. Area of Adaptation and Use Catskill grows well on gravelly or sandy soils along streams but has performed well on silt loam and calcareous soils. It will tolerate periodic flooding only for a short period. Its massive root system allows it to tolerate drought conditions. It is found from Ontario, Canada to the New York- Pennsylvania border and is adapted to USDA hardiness zones 3b to 6b. ‘Catskill' dwarf sand cherry planted among rip rap, in New York. ‘Catskill’ dwarf sand cherry (Prunus pumila var. depressa Establishment and Management for Conservation (L.)) was released in 1997, by the USDA Natural Plantings Resources Conservation Service (NRCS), Big Flats Plant Establishment: Planting 1-0 nursery bare root stock of Materials Center and the Pennsylvania Game Commission Catskill is the preferred method of establishment. for its prostrate growth habit and immense root system. Planting should be in the spring, prior to June 1st, or in the fall after October 10th. The stock should be dormant at Description the time of planting. -

Wild Plums Cherry Plums Sand Cherries

wild plums cherry plums sand cherries Wild plums, sand cherries, and cherry plums have ripening. Fruit varies from 1 to 1 ½ inch in diameter, the distinct plum characteristics of sour skins, sweet and fruits with soft, sweet flesh tend to be larger. flesh that sticks tightly to the pit, and pits that are flatter than they are round. Plants vary from shrubs to small trees. Wild plums (Prunus americana) are native to much of the U.S. North America is host to a variety of distinct plum species, but the only species widely planted in Minnesota is P. americana. Wild plums are typically large shrubs or small trees that sucker profusely, often sending out root suckers that sprout 20 or more feet from the mother plant. The fruit flesh is yellow, while the skin color varies from yellow to red, with the most common color being a red blush. Like most wild plants that are propagated from seeds, fruit quality varies tremendously. The best quality fruit has thick, sour skins, with sweet flesh that clings tightly to the pit. Some trees produce fruit with the texture of a golf ball that does not soften during Figure 41. Edible wild plums perennial fruit for northern climates 83 Sand cherries are small, native shrubs which Cherry plum is kind of a catch-all term for a number produce a small fruit that is closer to plums than of small fruited plums that belong to several related cherries. In some literature, all sand cherries are put species. Most produce red or purple fruit. -

Botanical Name Common Name

Approved Approved & as a eligible to Not eligible to Approved as Frontage fulfill other fulfill other Type of plant a Street Tree Tree standards standards Heritage Tree Tree Heritage Species Botanical Name Common name Native Abelia x grandiflora Glossy Abelia Shrub, Deciduous No No No Yes White Forsytha; Korean Abeliophyllum distichum Shrub, Deciduous No No No Yes Abelialeaf Acanthropanax Fiveleaf Aralia Shrub, Deciduous No No No Yes sieboldianus Acer ginnala Amur Maple Shrub, Deciduous No No No Yes Aesculus parviflora Bottlebrush Buckeye Shrub, Deciduous No No No Yes Aesculus pavia Red Buckeye Shrub, Deciduous No No Yes Yes Alnus incana ssp. rugosa Speckled Alder Shrub, Deciduous Yes No No Yes Alnus serrulata Hazel Alder Shrub, Deciduous Yes No No Yes Amelanchier humilis Low Serviceberry Shrub, Deciduous Yes No No Yes Amelanchier stolonifera Running Serviceberry Shrub, Deciduous Yes No No Yes False Indigo Bush; Amorpha fruticosa Desert False Indigo; Shrub, Deciduous Yes No No No Not eligible Bastard Indigo Aronia arbutifolia Red Chokeberry Shrub, Deciduous Yes No No Yes Aronia melanocarpa Black Chokeberry Shrub, Deciduous Yes No No Yes Aronia prunifolia Purple Chokeberry Shrub, Deciduous Yes No No Yes Groundsel-Bush; Eastern Baccharis halimifolia Shrub, Deciduous No No Yes Yes Baccharis Summer Cypress; Bassia scoparia Shrub, Deciduous No No No Yes Burning-Bush Berberis canadensis American Barberry Shrub, Deciduous Yes No No Yes Common Barberry; Berberis vulgaris Shrub, Deciduous No No No No Not eligible European Barberry Betula pumila -

![ENABLING MARKER-ASSISTED BREEDING (MAB) for BLUSH in PEACH [Prunus Persica (L.) Batsch] Terrence Frett Clemson University, Terrencefrett@Gmail.Com](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1876/enabling-marker-assisted-breeding-mab-for-blush-in-peach-prunus-persica-l-batsch-terrence-frett-clemson-university-terrencefrett-gmail-com-1411876.webp)

ENABLING MARKER-ASSISTED BREEDING (MAB) for BLUSH in PEACH [Prunus Persica (L.) Batsch] Terrence Frett Clemson University, [email protected]

Clemson University TigerPrints All Theses Theses 5-2012 ENABLING MARKER-ASSISTED BREEDING (MAB) FOR BLUSH IN PEACH [Prunus persica (L.) Batsch] Terrence Frett Clemson University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses Part of the Plant Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Frett, Terrence, "ENABLING MARKER-ASSISTED BREEDING (MAB) FOR BLUSH IN PEACH [Prunus persica (L.) Batsch]" (2012). All Theses. 1301. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses/1301 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ENABLING MARKER-ASSISTED BREEDING (MAB) FOR BLUSH IN PEACH [Prunus persica (L.) Batsch] A Thesis Presented to the Graduate School of Clemson University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science Horticulture by Terrence J. Frett May 2012 Committee Members: Dr. Ksenija Gasic, Committee Chair Dr. Gregory Reighard Dr. Desmond Layne Dr. Douglas Bielenberg ABSTRACT Phenotyping is a crucial component for using DNA-based tools in gene discovery and marker development. Phenotypic and genotypic data are essential for linking genetic variation with biological function, thus documenting gene function. However, phenotypic data gathering is not keeping pace with the immensely increasing amount of available genomic information, brought forth by current High Throughput technologies. Standardized phenotyping protocols for peach [Prunus persica (L.) Batsch] have been developed for 6 productivity traits (on the tree) and 16 fruit quality traits. Documentation of fruit quality phenotypes has been performed applying developed standardized phenotyping protocol in two seasons, at nine locations, on 513 peach and almond accessions, cultivars, advanced selections, lines, and or populations. -

Native Pollinator Plants by Season of Bloom

Native Pollinator Plants by Season of Bloom Extended list of forage and host plants for bees, butterflies and moths Very early spring SHRUBS PERENNIALS American hazelnut, Corylus americana, Bloodroot, Sanguinaria Canadensis C. cornuta Sand/moss phlox, Phlox bifida & P. subulata American honeysuckle, Lonicera canadensis Pussy willow, Salix discolor Shadbush, Amerlanchier canadensis, A. laevis Bloodroot, © Lisa Looke Early spring SHRUBS PERENNIALS Bayberry, Morella caroliniensis Blue cohosh, Caulophyllum thalictroides Flowering big-bracted dogwood, Benthamidia Dutchman’s breeches, Dicentra cucullaria florida Crested Iris, Iris cristata* Hobblebush, Viburnum lanatanoides Golden groundsel, Packera aurea Red eldeberry, Sambucus pubens Spicebush, Lindera benzoin Marsh marigold, Caltha palustrus Sweet fern, Comptonia peregrina Pussytoes, Antennaria spp. Sweetgale, Myrica gale Rue anemone, Thalictrum thalictroides Wild plums Violets, Viola adunca, V. cuccularia Beach plum, Prunus maritima Virginia bluebells, Mertensia virginica* Canada plum, Prunus nigra Marsh marigold, © Lisa Looke Sand plum, Prunus pumila Mid-spring SHRUBS PERENNIALS (continued) Bearberry, Arctostaphylos uva-ursi Canada wild ginger, Asarum canadense Black huckleberry, Gaylussacia baccata Common golden Alexanders, Zizia aurea Blueberry, Vaccinium spp. Early meadow-rue, Thalictrum dioicum Eastern shooting star, Dodecatheon meadia* Chokeberry, Aronia arbutifolia & Aronia Foam flower, Tiarella cordifolia melanocarpa Heart-leaved golden Alexanders, Zizia aptera Common snowberry, Symphoricarpos albus Jacob’s ladder, Polemonium reptans* Fragrant sumac, Rhus aromatica* King Solomon’s-seal, Polygonatum biflorum Mountain maple, Acer spicatum var. commutaturn Nannyberry, Viburnum lentago Large-leaved pussytoes, Antennaria Red buckeye, Aesculus pavia* plantaginifolia Nodding onion, Alium cernuum* Spotted crane’s-bill, © Lisa Looke Redbud, Cersis canadensis* Striped maple, Acer pennsylvanicum Red baneberry, Actaea rubra Red columbine, Aquilegia canadensis Solomon’s plume, Maianthemum racemosum PERENNIALS (syn. -

Dictionary of Cultivated Plants and Their Regions of Diversity Second Edition Revised Of: A.C

Dictionary of cultivated plants and their regions of diversity Second edition revised of: A.C. Zeven and P.M. Zhukovsky, 1975, Dictionary of cultivated plants and their centres of diversity 'N -'\:K 1~ Li Dictionary of cultivated plants and their regions of diversity Excluding most ornamentals, forest trees and lower plants A.C. Zeven andJ.M.J, de Wet K pudoc Centre for Agricultural Publishing and Documentation Wageningen - 1982 ~T—^/-/- /+<>?- •/ CIP-GEGEVENS Zeven, A.C. Dictionary ofcultivate d plants andthei rregion so f diversity: excluding mostornamentals ,fores t treesan d lowerplant s/ A.C .Zeve n andJ.M.J ,d eWet .- Wageninge n : Pudoc. -11 1 Herz,uitg . van:Dictionar y of cultivatedplant s andthei r centreso fdiversit y /A.C .Zeve n andP.M . Zhukovsky, 1975.- Me t index,lit .opg . ISBN 90-220-0785-5 SISO63 2UD C63 3 Trefw.:plantenteelt . ISBN 90-220-0785-5 ©Centre forAgricultura l Publishing and Documentation, Wageningen,1982 . Nopar t of thisboo k mayb e reproduced andpublishe d in any form,b y print, photoprint,microfil m or any othermean swithou t written permission from thepublisher . Contents Preface 7 History of thewor k 8 Origins of agriculture anddomesticatio n ofplant s Cradles of agriculture and regions of diversity 21 1 Chinese-Japanese Region 32 2 Indochinese-IndonesianRegio n 48 3 Australian Region 65 4 Hindustani Region 70 5 Central AsianRegio n 81 6 NearEaster n Region 87 7 Mediterranean Region 103 8 African Region 121 9 European-Siberian Region 148 10 South American Region 164 11 CentralAmerica n andMexica n Region 185 12 NorthAmerica n Region 199 Specieswithou t an identified region 207 References 209 Indexo fbotanica l names 228 Preface The aimo f thiswor k ist ogiv e thereade r quick reference toth e regionso f diversity ofcultivate d plants.Fo r important crops,region so fdiversit y of related wild species areals opresented .Wil d species areofte nusefu l sources of genes to improve thevalu eo fcrops . -

New Varieties

NEW2021 VARIETIES AUTUMN INFERNO® COTONEASTER Cotoneaster ‘Bronfire’ PP30,493 USDA Hardiness Zone: 5 AHS Heat Zone: 7 Height: 5-6’ Spread: 4-5’ Exposure: Full Sun to Part Shade Shape: Upright- Arching Discovered at Bron & Sons Nursery in British Columbia, this new Cotoneaster is a natural cross between C. lucidus and C. apiculatus. It has many of the attributes of C. lucidus that we so love for a hedge - great form, easily pruned, great foliage all season long plus great fall color. But what we really love about Autumn Inferno® is the small red berries formed along the stems in fall. The berries stay on the plant until the birds come and take them, no mess involved. Perfect as a pruned formal hedge or let it go natural. Just enough height to block off your annoying neighbors. FIRSTEDITIONSPLANTS.COM Plant patent has been applied for and trademark has been declared. Propagation and/or use of trademark without license is prohibited. GALACTIC PINK® CHASTETREE Vitex agnus-castus ‘Bailtextwo’ PP30,852 USDA Hardiness Zone: 6 AHS Heat Zone: 9 Height: 6-8’ Spread: 6-8’ Exposure: Full Sun Shape: Upright - Rounded Galactic Pink® has flowers that are a beautiful shade of pink and intermediate in size. The fragrant flowers, born in longGalactic panicles, Pink® bloomhas flowers from Junethat areto Octobera beautiful and shade attract of pollinatorspink and intermediate by the dozens. in size. The The darkfragrant green flowers, foliage is cleanborn and in the long branching panicles, bloomis dense from and June full. toMaturing October atand a slightly attract pollinatorssmaller size by than the dozens.Delta Blues™. -

Myzus Persicae (Sulzer) APHID”

Universidad de Talca FACULTAD DE CIENCIAS AGRARIAS UNIVERSIDAD DE TALCA - CHILE AND COMMUNAUTE FRANCAISE DE BELGIQUE ACADEMIE UNIVERSITAIRE WALLONIE-EUROPE UNIVERSITE DE LIEGE – GEMBLOUX AGRO-BIO TECH - BELGIQUE “DEFENSIVE RESPONSE OF COMMERCIAL VARIETIES OF Prunus persica L. TO THE ATTACK OF Myzus persicae (Sulzer) APHID” JAIME VERDUGO LEAL Thesis presented for obtaining the degree of Doctor en Ciencias Agrarias (U. de Talca) and Docteur en Sciences Agronomiques et Ingénierie Biologique (U. de Liège) Thesis Directors: Dr. Claudio Ramírez R. (U. de Talca - Chile) Dr. Frederic Francis (U. de Liège - Bélgica) TALCA – CHILE 2012 DIRECTOR OF PhD THESIS Thesis Director: Dr. Claudio C. Ramirez Thesis Director: Dr. Frederic Francis COMMITTEE OF EVALUATION: Dr. Eduardo Fuentes, Universidad de Talca PhD. Peter Caligari, Universidad de Talca Dr. Christian Figueroa, Universidad Austral de Chile Copyright. Under the Chilean and Belgium laws on copyright, only the author has the right to reproduce partially or completely the book in any way and manner whatsoever or to authorize the partial or complete reproduction in any manner in any form whatsoever. Photocopying or reproduction in another form is in violation of the said Act and subsequent amendments. Verdugo, J.A. (2011). Defensive response of commercial varieties of Prunus persica L. to the attack of Myzus persicae (Sulzer) aphid. (PhD Thesis). Facultad de Ciencias Agrarias – Universidad de Talca – Chile and Gembloux, Université de Liège – Gembloux Agro-Bio Tech, Belgium. Abstract Peaches and nectarines are among the most important fruit worldwide. Unfortunately, they are heavily attacked by the aphid M. persicae causing direct and indirect damages. In Chile, peaches and nectarines are also important fruit products. -

Chapter 14 Peach

Chapter 14 Peach David H. Byrne , Maria Bassols Raseira , Daniele Bassi , Maria Claudia Piagnani , Ksenija Gasic , Gregory L. Reighard , María Angeles Moreno , and Salvador Pérez Abstract The peach is the third most produced temperate tree fruit species behind apple and pear. This diploid species, Prunus persica , is naturally self-pollinating unlike most of the other cultivated Prunus species. Its center of diversity is in China, where it was domesticated. Starting about 3,000 years ago, the peach was moved from China to all temperate and subtropical climates within the Asian continent and then, more than 2,000 years ago, spread to Persia (present day Iran) via the Silk Road and from there throughout Europe. From Europe it was taken by the Spanish and Portuguese explorers to the Americas. It has an extensive history of breeding D. H. Byrne (*) Department of Horticultural Sciences , Texas A&M University , College Station , TX , USA e-mail: [email protected] M. B. Raseira EMBRAPA – Clima Temperado , BR 392 km 78 – Cx. , Postal 403 , Pelotas 96001-970 , RS , Brazil e-mail: [email protected] D. Bassi • M. C. Piagnani Dipartimento di Produzione Vegetale , Università degli Studi di Milano , Milan , Italy e-mail: [email protected] ; [email protected] K. Gasic • G. L. Reighard Department of Environmental Horticulture , Clemson University , Clemson , SC , USA e-mail: [email protected] ; [email protected] M. A. Moreno Estación Experimental de Aula Dei (CSIC) , Zaragoza , Spain e-mail: [email protected] S. Pérez Recursos Genéticos y Mejoramiento de Prunus, Guillermo Prieto 14 , Centro , Querétaro Qro. 76000 , Mexico e-mail: [email protected] M.L. -

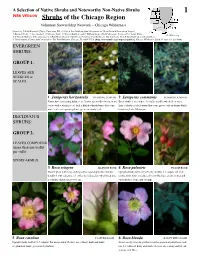

Shrubs of the Chicago Region

A Selection of Native Shrubs and Noteworthy Non-Native Shrubs 1 WEB VERSION Shrubs of the Chicago Region Volunteer Stewardship Network – Chicago Wilderness Photos by: © Paul Rothrock (Taylor University, IN), © John & Jane Balaban ([email protected]; North Branch Restoration Project), © Kenneth Dritz, © Sue Auerbach, © Melanie Gunn, © Sharon Shattuck, and © William Burger (Field Museum). Produced by: Jennie Kluse © vPlants.org and Sharon Shattuck, with assistance from Ken Klick (Lake County Forest Preserve), Paul Rothrock, Sue Auerbach, John & Jane Balaban, and Laurel Ross. © Environment, Culture and Conservation, The Field Museum, Chicago, IL 60605 USA. [http://www.fmnh.org/temperateguides/]. Chicago Wilderness Guide #5 version 1 (06/2008) EVERGREEN SHRUBS: GROUP 1. LEAVES ARE NEEDLES or SCALES. 1 Juniperus horizontalis TRAILING JUNIPER: 2 Juniperus communis COMMON JUNIPER: Plants have a creeping habit; some leaves are needles but most are Erect shrub or tree (up to 3 m tall); needles whorled on stem; scales with a whitish coat; fruit a bluish-whitish berry-like cone; fruit a bluish or black berry-like cone; grows only in dunes/bluffs male cones on separate plants; grows in sandy soils. bordering Lake Michigan. DECIDUOUS SHRUBS: GROUP 2. LEAVES COMPOUND (more than one leaflet per stalk). STEMS ARMED. 3 Rosa setigera ILLINOIS ROSE: 4 Rosa palustris SWAMP ROSE: Mature plant with long-arching stems; sparse prickles; leaflets Upright shrub; stems very thorny; leaflets 5-7; sepals fall from usually 3, but sometimes 5; styles (female pollen tube) fused into mature fruit; fruit smooth, red berry-like hips; grows in wet and a column; stipules narrow to tip. open ditches, bogs, and swamps. -

Common and Scientific Names of Ornamental Crops

This is a section from the 2012 DISEASE CONTROL RECOMMENDATIONS FOR ORNAMENTAL CROPS Publication E036 The full manual, containing recommendations specific to New Jersey, can be found on the Rutgers NJAES website in the publications section: njaes.rutgers.edu/pubs/publication.asp?pid=E036 Note: The label is a legally-binding contract between the user and the manufacturer. The user must fol- low all rates and restrictions as per label directions. The use of any pesticide inconsistent with the label directions is a violation of Federal law. Mention or display of a trademark, proprietary product, or firm in text or figures does not constitute an endorsement by Rutgers Cooperative Extension and does not imply approval to the exclusion of other suitable products or firms. © 2012 Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey. All rights reserved. Revised: June 2012 Cooperating Agencies: Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, U.S. Department of Agriculture, and County Boards of Chosen Freeholders, Rutgers Cooperative Exten- sion, a unit of the New Jersey Agricultural Experiment Station, is an equal opportunity program provider and employer. 2012 DISEASE CONTROL RECOMMENDATIONS FOR ORNAMENTAL CROPS Section III Common and Scientifi c Names of Ornamental Crops Note: Host plants are listed on pesticide labels by common or scientifi c name. Below is a list of plants included on the label of one or more pesticide products. Hosts denoted by an “x” are included in Section I, Disease Recommendations by Crop. Common name Other common names Scientifi c name x Abelia Abelia spp. Abutilon Velvetleaf, Chinese Lantern, Mallow, Abutilon spp. Flowering Maple Acacia Thorntree Acacia spp.