Writing Boston: Graffiti Bombing As Community Publishing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

This Is Modern Art 2014/15 Season Lisa Portes Lisa

SAVERIO TRUGLIA PHOTOGRAPHY BY PHOTOGRAPHY BY 2014/15 SEASON STUDY GUIDE THIS IS MODERN ART (BASED ON TRUE EVENTS) WRITTEN BY IDRIS GOODWIN AND KEVIN COVAL DIRECTED BY LISA PORTES FEBRUARY 25 – MARCH 14, 2015 INDEX: 2 WELCOME LETTER 4 PLAY SYNOPSIS 6 COVERAGE OF INCIDENT AT ART INSTITUTE: MODERN ART. MADE YOU LOOK. 7 CHARACTER DESCRIPTIONS 8 PROFILE OF A GRAFFITI WRITER: MIGUEL ‘KANE ONE’ AGUILAR 12 WRITING ON THE WALL: GRAFFITI GIVES A VOICE TO THE VOICELESS with classroom activity 16 BRINGING CHICAGO’S URBAN LANDSCAPE TO THE STEPPENWOLF STAGE: A CONVERSATION WITH PLAYWRIGHT DEAR TEACHERS: IDRIS GOODWIN 18 THE EVOLUTION OF GRAFFITI IN THE UNITED STATES THANK YOU FOR JOINING STEPPENWOLF FOR YOUNG ADULTS FOR OUR SECOND 20 COMMON CORE STATE STANDARDS SHOW OF 2014/15 SEASON: CREATE A MOVEMENT: THE ART OF A REVOLUTION. 21 ADDITIONAL RESOURCES 22 NEXT UP: PROJECT COMPASS In This Is Modern Art, we witness a crew of graffiti writers, Please see page 20 for a detailed outline of the standards Made U Look (MUL), wrestling with the best way to make met in this guide. If you need further information about 23 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS people take notice of the art they are creating. They choose the way our work aligns with the standards, please let to bomb the outside of the Art Institute to show theirs is us know. a legitimate, worthy and complex art form born from a rich legacy, that their graffiti is modern art. As the character of As always, we look forward to continuing the conversations Seven tells us, ‘This is a chance to show people that there fostered on stage in your classrooms, through this guide are real artists in this city. -

Moral Rights: the Anti-Rebellion Graffiti Heritage of 5Pointz Richard H

digitalcommons.nyls.edu Faculty Scholarship Articles & Chapters 2018 Moral Rights: The Anti-Rebellion Graffiti Heritage of 5Pointz Richard H. Chused New York Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.nyls.edu/fac_articles_chapters Part of the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, Land Use Law Commons, and the Property Law and Real Estate Commons Recommended Citation Chused, Richard H., "Moral Rights: The Anti-Rebellion Graffiti Heritage of 5Pointz" (2018). Articles & Chapters. 1172. https://digitalcommons.nyls.edu/fac_articles_chapters/1172 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at DigitalCommons@NYLS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles & Chapters by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@NYLS. Moral Rights: The Anti-Rebellion Graffiti Heritage of 5Pointz Richard Chused* INTRODUCTION Graffiti has blossomed into far more than spray-painted tags and quickly vanishing pieces on abandoned buildings, trains, subway cars, and remote underpasses painted by rebellious urbanites. In some quarters, it has become high art. Works by acclaimed street artists Shepard Fairey, Jean-Michel Basquiat,2 and Banksy,3 among many others, are now highly prized. Though Banksy has consistently refused to sell his work and objected to others doing so, works of other * Professor of Law, New York Law School. I must give a heartfelt, special thank you to my artist wife and muse, Elizabeth Langer, for her careful reading and constructive critiques of various drafts of this essay. Her insights about art are deeply embedded in both this paper and my psyche. Familial thanks are also due to our son, Benjamin Chused, whose knowledge of the graffiti world was especially helpful in composing this paper. -

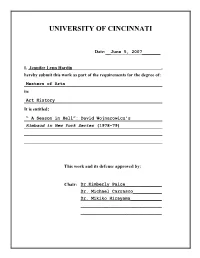

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date:__June 5, 2007_______ I, Jennifer Lynn Hardin_______________________________________, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Masters of Arts in: Art History It is entitled: “ A Season in Hell”: David Wojnarowicz’s Rimbaud in New York Series (1978-79) This work and its defense approved by: Chair: Dr.Kimberly Paice______________ Dr. Michael Carrasco___________ Dr. Mikiko Hirayama____________ _______________________________ _______________________________ “A Season in Hell”: David Wojnarowicz’s Rimbaud In New York Series (1978-79) A thesis submitted to the Art History Faculty of the College of Design, Architecture, Art, and Planning University of Cincinnati In candidacy for the degree of Masters of Arts in Art History Jennifer Hardin June 2007 Advisor: Dr. Kimberly Paice Abstract David Wojnarowicz (1954-1992) was an interdisciplinary artist who rejected traditional scholarship and was suspicious of institutions. Wojnarowicz’s Arthur Rimbaud in New York series (1978-79) is his earliest complete body of work. In the series a friend wears the visage of the French symbolist poet. My discussion of the photographs involves how they convey Wojnarowicz’s notion of the city. In chapter one I discuss Rimbaud’s conception of the modern city and how Wojnarowicz evokes the figure of the flâneur in establishing a link with nineteenth century Paris. In the final chapters I address the issue of the control of the city and an individual’s right to the city. In chapter two I draw a connection between the renovations of Paris by Baron George Eugène Haussman and the gentrification Wojnarowicz witnessed of the Lower East side. -

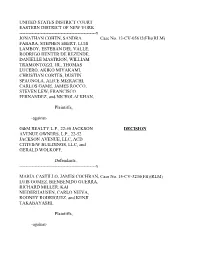

5Pointz Decision

Case 1:13-cv-05612-FB-RLM Document 172 Filed 02/12/18 Page 1 of 100 PageID #: 4939 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT EASTERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK --------------------------------------------------x JONATHAN COHEN, SANDRA Case No. 13-CV-05612(FB)(RLM) FABARA, STEPHEN EBERT, LUIS LAMBOY, ESTEBAN DEL VALLE, RODRIGO HENTER DE REZENDE, DANIELLE MASTRION, WILLIAM TRAMONTOZZI, JR., THOMAS LUCERO, AKIKO MIYAKAMI, CHRISTIAN CORTES, DUSTIN SPAGNOLA, ALICE MIZRACHI, CARLOS GAME, JAMES ROCCO, STEVEN LEW, FRANCISCO FERNANDEZ, and NICHOLAI KHAN, Plaintiffs, -against- G&M REALTY L.P., 22-50 JACKSON DECISION AVENUE OWNERS, L.P., 22-52 JACKSON AVENUE, LLC, ACD CITIVIEW BUILDINGS, LLC, and GERALD WOLKOFF, Defendants. --------------------------------------------------x MARIA CASTILLO, JAMES COCHRAN, Case No. 15-CV-3230(FB)(RLM) LUIS GOMEZ, BIENBENIDO GUERRA, RICHARD MILLER, KAI NIEDERHAUSEN, CARLO NIEVA, RODNEY RODRIGUEZ, and KENJI TAKABAYASHI, Plaintiffs, -against- Case 1:13-cv-05612-FB-RLM Document 172 Filed 02/12/18 Page 2 of 100 PageID #: 4940 G&M REALTY L.P., 22-50 JACKSON AVENUE OWNERS, L.P., 22-52 JACKSON AVENUE, LLC, ACD CITIVIEW BUILDINGS, LLC, and GERALD WOLKOFF, Defendants. -----------------------------------------------x Appearances: For the Plaintiff For the Defendant ERIC BAUM DAVID G. EBERT ANDREW MILLER MIOKO TAJIKA Eisenberg & Baum LLP Ingram Yuzek Gainen Carroll & 24 Union Square East Bertolotti, LLP New York, NY 10003 250 Park Avenue New York, NY 10177 BLOCK, Senior District Judge: TABLE OF CONTENTS I ..................................................................5 II ..................................................................6 A. The Relevant Statutory Framework . 7 B. The Advisory Jury . 11 C. The Witnesses and Evidentiary Landscape. 13 2 Case 1:13-cv-05612-FB-RLM Document 172 Filed 02/12/18 Page 3 of 100 PageID #: 4941 III ................................................................16 A. -

Illstyle and Peace Study Guide

STUDY GUIDE Illstyle and Peace Productions Useful Vocabulary and Terms to Share Break beat: The beat of the most danceable section of a song. Popping: A street dance style based upon the Additional Resources technique of quickly contracting and relaxing muscles to cause a jerk in the dancer’s body Johan Kugelberg, Born in the Bronx; a visual record Locking: A dance style relying on perfect timing and of the early days of hip hop NYPL link frequent “locking” of limbs in time with music. 6 step: A basic hip-hop move in which the dancer’s Jeff Chang , Can’t Stop, Won’t Stop NYPL link arms support the body which spins in a circle above the floor. Eric Felisbret, Graffiti New York NYPL link Downrock: All breakdance moves performed with a part of the body (other than the feet) is in Bronx Rhymes interactive map contact with the floor. http://turbulence.org/Works/bronx_rhymes/what.html Smithsonian article on birth of hip-hop: http://invention.smithsonian.org/resources/online_arti Background Information for Students cles_detail.aspx?id=646 There are four essential elements of hip-hop: 5 Pointz, New York Graffiti Mecca: http://5ptz.com/ DJing: The art of spinning records and using two turn- NY Times Articles on 5 Pointz: tables to create your own instrument. http://goo.gl/i1F2I0 Also the art of touching and moving records with your hands. http://goo.gl/kOCFnv Breakdancing: A style of dancing that includes gymnastic moves, head spins, and backspins. Young 5Pointz Buzzfeed article with photos: people who were into dancing to the “breaks” at Bronx http://goo.gl/1ItqX9 parties started calling themselves B-boys and B-girls, and their style of dancing came to be known as NY Times Article on Taki183, one of the first taggers breakdancing. -

App. 1 950 F.3D 155 (2D Cir. 2020) United States Court of Appeals

App. 1 950 F.3d 155 (2d Cir. 2020) United States Court of Appeals, Second Circuit Maria CASTILLO, James Cochran, Luis Gomez, Bien- benido Guerra, Richard Miller, Carlo Nieva, Kenji Taka- bayashi, Nicholai Khan, Plaintiffs-Appellees, Jonathan Cohen, Sandra Fabara, Luis Lamboy, Esteban Del Valle, Rodrigo Henter De Rezende, William Tramon- tozzi, Jr., Thomas Lucero, Akiko Miyakami, Christian Cortes, Carlos Game, James Rocco, Steven Lew, Francisco Fernandez, Plaintiffs-Counter- Defendants-Appellees, Kai Niederhause, Rodney Rodriguez, Plaintiffs, v. G&M REALTY L.P., 22-50 Jackson Avenue Owners, L.P., 22-52 Jackson Avenue LLC, ACD Citiview Buildings, LLC, and Gerald Wolkoff, Defendants-Appellants. Nos. 18-498-cv (L), 18-538-cv (CON) August Term 2019 Appeal from the United States District Court for the Eastern District of New York Nos. 15-cv-3230 (FB) (RLM), 13-cv-5612 (FB) (RLM), Frederic Block, District Judge, Presiding. Argued August 30, 2020 Decided February 20, 2020 Amended February 21, 2020 Attorneys and Law Firms ERIC M. BAUM (Juyoun Han, Eisenberg & Baum, LLP, New York, NY, Christopher J. Robinson, Rottenberg Lipman Rich, P.C., New York, NY, on the brief), Eisenberg & Baum, LLP, New York, NY, for Plaintiffs-Appellees. MEIR FEDER (James M. Gross, on the brief), Jones Day, New York, NY, for Defendants-Appellants. App. 2 Before: PARKER, RAGGI, and LOHIER, Circuit Judges. BARRINGTON D. PARKER, Circuit Judge: Defendants‐Appellants G&M Realty L.P., 22‐50 Jack- son Avenue Owners, L.P., 22‐52 Jackson Avenue LLC, ACD Citiview Buildings, LLC, and Gerald Wolkoff (collec- tively “Wolkoff”) appeal from a judgment of the United States District Court for the Eastern District of New York (Frederic Block, J.). -

Street Art Rising Marshall Soules—[email protected]

Vol 1 No 2 (Autumn 2020) Online: jps.library.utoronto.ca/index.php/nexj Visit our WebBlog: newexplorations.net Street Art Rising Marshall Soules—[email protected] This illustrated article discusses the various manifestations of street art—graffiti, posters, stencils, social murals—and the impact of street art on urban environments. Continuing perceptions of street art as vandalism contributing to urban decay neglects to account for street art’s full spectrum of effects. As freedom of expression protected by law, as news from under-privileged classes, as images of social uplift and consciousness-raising, and as beautification of urban milieux, street art has social benefits requiring re-assessment. Street art has become a significant global art movement. Detailed contextual history includes the photographer Brassai's interest in Parisian graffiti between the world wars; Cézanne’s use of passage; Walter Benjamin's assemblage of fragments in The Arcades Project; the practice of dérive (passage through diverse ambiances, drifting) and détournement (rerouting, hijacking) as social and political intervention advocated by Guy Debord and the Situationist International; Dada and Surrealist montage and collage; and the art of Quebec Automatists and French Nouveaux réalistes. Present street art engages dynamically with 20th C. art history. The article explores McLuhan’s ideas about the power of mosaic style to subvert the received order, opening spaces for new discourse to emerge, new patterns to be discovered. The author compares street art to advertising, and raises questions about appropriation, authenticity, and style. How does street art survive when it leaves the streets for galleries, design shops, and museums? Street art continues to challenge communication strategies of the privileged classes and elected officials, and increasingly plays a reconstructive role in modulating the emotional tenor of urban spaces. -

Public Art, Cultural Landscapes, and Urban Space in Venice, California

The Contours of Creativity: Public Art, Cultural Landscapes, and Urban Space in Venice, California Zia Salim California State University, Fullerton Abstract This cross-sectional study examines spatial and thematic patterns of public art in Venice, Los Angeles’s bohemian beach community, to de- termine how public wall art marks the cultural landscape. To do this, 353 items of public art were field surveyed, photographed, and mapped, with the resulting inventory being subjected to content analysis. Data from secondary sources, including the city’s history and demographics, were used to contextualize the results. The results indicate that most public art is located on commercial buildings, with a smaller concentration on residential buildings. A majority of public art in Venice includes three main types of elements: local elements, people, and nature. Although public art is an especially dynamic and ephemeral subject of study, I conclude that an analysis of the locations and themes of public art helps to explain its aesthetic and historic functions and demonstrates its role in Venice’s cultural landscape. Keywords: cultural landscape, public art, street art, murals, Venice Introduction The beach community of Venice is the eclectic epicenter of Los Angeles: for decades wanderers, non-conformers, hippies, and tourists have congregated in this seaside spot to partake in Venice’s unconventional atmosphere and unique architecture. Images of the beach, the boardwalk, and the canals and their bungalows are predominant in popular imaginations of Venice’s urban geography, while popular understandings of Venice’s social geography con- sider its (counter)cultural dimensions as a haven for poets and performers, surfers and skaters, bodybuilders and bohemians, musicians and mystics, and spiritualists and free spirits. -

When the Wall Talks: a Semiotics Analysis of Graffiti Tagged by “Act Move”

When The Wall Talks: A Semiotics Analysis of Graffiti Tagged by “Act Move” A Journal Paper Hasan IbnuSafruddin (0707848) English Education Department, Faculty of Language and Arts Education, Indonesia University of Education, Dr. Setiabudhi 229, Bandung 40154, Indonesia Email: [email protected] Abstract: In Indonesia Graffiti phenomenon has become a popular culture. Graffiti exists around us; in public space, wall, and toilet.Its existence sometime lasts just a few days then beingerased, but some other exists for a long time. Some people think graffiti is a kind of vandalism, some other think it is a piece of art. That makes the graffiti interesting to me. The author believe there must be a purpose and meaning in creating graffiti. Bandung city is popular as the place of creative people; there are many communities of Bomber, graffiti creator called.The author choose some graffiti tagged by Act Move around Bandung as the sample for my analysis. Different with other graffiti, Act Move more applies more the words form rather than pictures. In this paper the author would like to analyze five graffiti tagged by Act Move around Bandung city through the Roland Barthes framework. Barthes‟ Frame work isapplied to find out the meaning of graffiti. After doing descriptive analysis of the graffiti the author also do an interview with the Bomber of Act Move to enrich the data and make the clear understanding of this study. The finding of this study is the meaning of denotation, connotation and myth or ideology of the graffiti. The author expect this study can give the exploration and interpretation the meaning beyond and surface of graffiti. -

United States District Court Eastern District of New York

Case 1:13-cv-05612-FB-RLM Document 189-1 Filed 03/15/18 Page 1 of 41 PageID #: 5697 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT EASTERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK -------------------------------------------------------------------- x JONATHAN COHEN, SANDRA FABARA, : STEPHEN EBERT, LUIS LAMBOY, ESTEBAN : DEL VALLE, RODRIGO HENTER DE REZENDE, : Index No. 13-cv-05612 (FB) (RLM) DANIELLE MASTRION, WILLIAM : TRAMONTOZZI, JR., THOMAS LUCERO, AKIKO : MIYAKAMI, CHRISTIAN CORTES, DUSTIN : Hon. Frederic Block SPAGNOLA, ALICE MIZRACHI, CARLOS GAME, : JAMES ROCCO, STEVEN LEW, FRANCISCO : DEFENDANTS’ FED. R. CIV. P. FERNANDEZ, and NICHOLAI KHAN, : 52 AND 59 MEMORANDUM IN : SUPPORT OF MOTION TO SET Plaintiffs, : ASIDE FINDINGS OF FACT : AND CONCLUSIONS OF LAW : -against- AND FOR A NEW TRIAL, OR : ALTERNATIVELY, TO : VACATE THE JUDGMENT IN G & M REALTY L.P., 22-50 JACKSON AVENUE : OWNERS, L.P., 22-52 JACKSON AVENUE, LLC, ACD PLAINTIFFS’ FAVOR AND : ENTER JUDGMENT FOR CITIVIEW BUILDINGS, LLC and GERALD : WOLKOFF, DEFENDANTS, OR : ALTERNATIVELY, : Defendants. FOR REMITTITUR -------------------------------------------------------------------- x : MARIA CASTILLO, JAMES COCHRAN, : LUIS GOMEZ, BIENBENIDO GUERRA, : Index No. 15-cv-03230 (FB) (RLM) RICHARD MILLER, KAI NIEDERHAUSEN, : CARLO NIEVA, RODNEY RODRIGUEZ, and : KENJI TAKABAYASHI, : : Plaintiffs, : : -against- : : : G & M REALTY L.P., 22-50 JACKSON AVENUE : OWNERS, L.P., 22-52 JACKSON AVENUE, LLC, ACD : CITIVIEW BUILDINGS, LLC and GERALD : WOLKOFF, : : Defendants. -------------------------------------------------------------------- -

C:\Users\Mikei\Appdata\Local\Temp

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT EASTERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK --------------------------------------------------x JONATHAN COHEN, SANDRA Case No. 13-CV-05612(FB)(RLM) FABARA, STEPHEN EBERT, LUIS LAMBOY, ESTEBAN DEL VALLE, RODRIGO HENTER DE REZENDE, DANIELLE MASTRION, WILLIAM TRAMONTOZZI, JR., THOMAS LUCERO, AKIKO MIYAKAMI, CHRISTIAN CORTES, DUSTIN SPAGNOLA, ALICE MIZRACHI, CARLOS GAME, JAMES ROCCO, STEVEN LEW, FRANCISCO FERNANDEZ, and NICHOLAI KHAN, Plaintiffs, -against- G&M REALTY L.P., 22-50 JACKSON DECISION AVENUE OWNERS, L.P., 22-52 JACKSON AVENUE, LLC, ACD CITIVIEW BUILDINGS, LLC, and GERALD WOLKOFF, Defendants. --------------------------------------------------x MARIA CASTILLO, JAMES COCHRAN, Case No. 15-CV-3230(FB)(RLM) LUIS GOMEZ, BIENBENIDO GUERRA, RICHARD MILLER, KAI NIEDERHAUSEN, CARLO NIEVA, RODNEY RODRIGUEZ, and KENJI TAKABAYASHI, Plaintiffs, -against- G&M REALTY L.P., 22-50 JACKSON AVENUE OWNERS, L.P., 22-52 JACKSON AVENUE, LLC, ACD CITIVIEW BUILDINGS, LLC, and GERALD WOLKOFF, Defendants. -----------------------------------------------x Appearances: For the Plaintiff For the Defendant ERIC BAUM MEIR FEDER ANDREW MILLER Jones Day Eisenberg & Baum LLP 250 Vesey Street 24 Union Square East New York, NY 10281 New York, NY 10003 DAVID G. EBERT MIOKO C. TAJIKA Ingram Yuzek Gainen Carroll & Bertolotti, LLP 250 Park Avenue New York, NY 10177 BLOCK, Senior District Judge: On February 12, 2018, I issued my decision granting plaintiffs $6,750,000 as statutory damages for the willful destruction of 45 of plaintiffs’ 49 works of visual art by defendant Gerald Wolkoff (“Wolkoff”). Cohen v. G&M Realty L.P., 2018 WL 851374, at *2 (E.D.N.Y. Feb. 12, 2018) (“Cohen II”).1 Defendants now move 1 The decision incorrectly states: “Plaintiffs, 21 aerosol artists, initiated this lawsuit over four years ago.” Cohen II, 2018 WL 851374, at *1 (E.D.N.Y. -

Street Art Of

Global Latin/o Americas Frederick Luis Aldama and Lourdes Torres, Series Editors “A detailed, incisive, intelligent, and well-argued exploration of visual politics in Chile that explores the way muralists, grafiteros, and other urban artists have inserted their aesthetics into the urban landscape. Not only is Latorre a savvy, patient sleuth but her dialogues with artists and audiences offer the reader precious historical context.” —ILAN STAVANS “A cutting-edge piece of art history, hybridized with cultural studies, and shaped by US people of color studies, attentive in a serious way to the historical and cultural context in which muralism and graffiti art arise and make sense in Chile.” —LAURA E. PERÉZ uisela Latorre’s Democracy on the Wall: Street Art of the Post-Dictatorship Era in Chile G documents and critically deconstructs the explosion of street art that emerged in Chile after the dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet, providing the first broad analysis of the visual vocabulary of Chile’s murals and graffiti while addressing the historical, social, and political context for this public art in Chile post-1990. Exploring the resurgence and impact of the muralist brigades, women graffiti artists, the phenomenon of “open-sky museums,” and the transnational impact on the development of Chilean street art, Latorre argues that mural and graffiti artists are enacting a “visual democracy,” a form of artistic praxis that seeks to create alternative images to those produced by institutions of power. Keenly aware of Latin America’s colonial legacy and Latorre deeply flawed democratic processes, and distrustful of hegemonic discourses promoted by government and corporate media, the artists in Democracy on the Wall utilize graffiti and muralism as an alternative means of public communication, one that does not serve capitalist or nationalist interests.