A Study Into the Validity of the Ship Design Spiral in Early Stage Ship Design

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Operation Kipion: Royal Navy Assets in the Persian by Claire Mills Gulf

BRIEFING PAPER Number 8628, 6 January 2020 Operation Kipion: Royal Navy assets in the Persian By Claire Mills Gulf 1. Historical presence: the Armilla Patrol The UK has maintained a permanent naval presence in the Gulf region since October 1980, when the Armilla Patrol was established to ensure the safety of British entitled merchant ships operating in the region during the Iran-Iraq conflict. Initially the Royal Navy’s presence was focused solely in the Gulf of Oman. However, as the conflict wore on both nations began attacking each other’s oil facilities and oil tankers bound for their respective ports, in what became known as the “tanker war” (1984-1988). Kuwaiti vessels carrying Iraqi oil were particularly susceptible to Iranian attack and foreign-flagged merchant vessels were often caught in the crossfire.1 In response to a number of incidents involving British registered vessels, in October 1986 the Royal Navy began accompanying British-registered vessels through the Straits of Hormuz and in the Persian Gulf. Later the UK’s Armilla Patrol contributed to the Multinational Interception Force (MIF), a naval contingent patrolling the Persian Gulf to enforce the UN-mandated trade embargo against Iraq, imposed after its invasion of Kuwait in August1990.2 In the aftermath of the 2003 Iraq conflict, Royal Navy vessels, deployed as part of the Armilla Patrol, were heavily committed to providing maritime security in the region, the protection of Iraq’s oil infrastructure and to assisting in the training of Iraqi sailors and marines. 1.1 Assets The Type 42 destroyer HMS Coventry was the first vessel to be deployed as part of the Armilla Patrol, followed by RFA Olwen. -

Defence and Security After Brexit Understanding the Possible Implications of the UK’S Decision to Leave the EU Compendium Report

Defence and security after Brexit Understanding the possible implications of the UK’s decision to leave the EU Compendium report James Black, Alex Hall, Kate Cox, Marta Kepe, Erik Silfversten For more information on this publication, visit www.rand.org/t/RR1786 Published by the RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, Calif., and Cambridge, UK © Copyright 2017 RAND Corporation R® is a registered trademark. Cover: HMS Vanguard (MoD/Crown copyright 2014); Royal Air Force Eurofighter Typhoon FGR4, A Chinook Helicopter of 18 Squadron, HMS Defender (MoD/Crown copyright 2016); Cyber Security at MoD (Crown copyright); Brexit (donfiore/fotolia); Heavily armed Police in London (davidf/iStock) RAND Europe is a not-for-profit organisation whose mission is to help improve policy and decisionmaking through research and analysis. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions of its research clients and sponsors. Limited Print and Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law. This representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for noncommercial use only. Unauthorized posting of this publication online is prohibited. Permission is given to duplicate this document for personal use only, as long as it is unaltered and complete. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of its research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please visit www.rand.org/pubs/permissions. Support RAND Make a tax-deductible charitable contribution at www.rand.org/giving/contribute www.rand.org www.rand.org/randeurope Defence and security after Brexit Preface This RAND study examines the potential defence and security implications of the United Kingdom’s (UK) decision to leave the European Union (‘Brexit’). -

Desidernov 2012 Issue 54

desiderNov 2012 Issue 54 Carriers – a ‘Made in the UK’ success story Variety of front line rations expands to include kosher food See inside Viking On way to Watch out for Rapid work Scout proves reborn the front line Murphy’s Law on the Rock pulling power FEATURES 25 22 Vikings are on the march again The Royal Marines' fleet of amphibious all-terrain vehicles known as Vikings are to be regenerated under a new £37 million contract with BAE Systems with work already starting Picture: Babcock Picture: at the company's plant in Sweden 24 Between a Rock and a hard place A badly-weathered radome on top of the Rock of Gibraltar, which houses a radar crucial to air traffic control around the territory's airfield, has been repaired in rapid time with the help of a DE&S team 26 Merlin gets shipshape Another milestone has been successfully passed in the programme to upgrade the Royal Navy's Merlin helicopters to Mark 2 standard with trials taking place on HMS Illustrious 28 Services take the taste test cover image The best culinary talent in the services, using some of the 2012 best ingredients served up by DE&S, have been battling it out in Exercise Joint Caterer in front of appreciative audiences at Prime Minister David Cameron has praised UK engineering skills during a visit to Rosyth to catch up Sandown Park Racecourse on progress on HMS Queen Elizabeth, the first of two aircraft carriers being built for the Royal Navy NOVEMBER desider NEWS Assistant Head, Public Relations: Ralph Dunn - 9352 30257 or 0117 9130257 6 Chinook heading to the front -

Desider: Issue 74, July 2014

July 2014 Issue 74 desthe magazine for defencidere equipment and support UK’s biggest warship ready for Royal naming Latest Finance and Military Capability wallchart See inside Perfectly Airseeker A warm Trucks on Families inspect formed take-off welcome the front line Abbey Wood FEATURES on 32 all 29 MASS production With demand for ammunition set to fall as UK Forces complete the drawdown from Afghanistan, DE&S' contract e: Andy F with BAE Systems Munitions will be moving into a new phase Pictur 32 Vanguard of power projection As the first of class Queen Elizabeth aircraft carrier is set to be named this month, DE&S' Director Ships Tony Graham looks back on the project's challenges and successes 36 New look Chinook The first of the Mk6 Chinooks, with improved handling qualities and stability, has been handed over to the RAF on time, less than three years after contract signing 42 Truck of war Reservists will have a vital role in Army 2020. The Army's heavy equipment transport service has been using Sponsored Reserves for the last ten years cover image 2014 The first of the Queen Elizabeth class aircraft carriers is Y 44 DE&S family together at Abbey Wood due to be officially named this month. Queen Elizabeth The first of this summer's Families Days at DE&S is in Rosyth where the various component parts have JUL headquarters has proved a resounding success been integrated following construction at yards around the country desider NEWS www.gov.uk/government/publications/desider 6 New Chair to bring about change Assistant Head, Corporate -

The Royal Navy's New Frigates and the National Shipbuilding Strategy: February 2017 Update

BRIEFING PAPER Number 7737, 2 February 2017 The Royal Navy's new frigates and the National By Louisa Brooke-Holland Shipbuilding Strategy: February 2017 update Contents: 1. Naval shipbuilding in the UK 2. The Navy’s new frigates 3. Offshore Patrol Vessels 4. Logistics ships 5. The Shipbuilding Strategy and the Parker report www.parliament.uk/commons-library | intranet.parliament.uk/commons-library | [email protected] | @commonslibrary 2 The Royal Navy's new frigates and the National Shipbuilding Strategy: February 2017 update Contents Summary 3 1. Naval shipbuilding in the UK 5 1.1 Naval shipbuilding in the UK 5 1.2 Complex warships built only in the UK? 9 1.3 Snapshot of the Shipbuilding Industry 10 2. The Navy’s new frigates 12 2.1 Will the Strategy lay out a build timetable? 13 2.2 No life extension for the Type 23 frigates 13 2.3 The Type 26 Global Combat Ship 14 2.4 The General Purpose Frigate (Type 31) 16 3. Offshore Patrol Vessels 20 4. Logistics ships 22 5. The Shipbuilding Strategy and the Parker report 23 5.1 Timeline of Government statements 23 5.2 Defence Committee recommendations 26 5.3 Sir John Parker’s report 26 5.4 Reaction 29 5.5 Government response to Defence Committee report 30 Appendix: the Royal Navy’s fleet 32 Contributing Authors: Chris Rhodes, Economic Policy and Statistics, section 2.3 Cover page image copyright HMS St Albans by Ministry of Defence. Licensed under the Open Government Licence / image cropped. HMS St Albans is a Type 23 frigate that is due to leave service in 2035. -

Sword & Shield

Sword & Shield HMS DEFENDER’s Periodical Newsletter Issue 09 | Spring 2020 A MESSAGE FROM THE COMMANDING OFFICER As HMS DEFENDER undertakes her journey back to Portsmouth, I reflect on what has been a hugely challenging but successful deployment. We have worked with our allies including the USA, India and Australia, promoting the right to Freedom of Navigation by escorting multiple merchant vessels through the Straits of Hormuz. The Ship visited many ports within the UAE and further afield, conducting Defence Engagement events in order to strengthen international diplomatic relationships. In January, I am sure you were aware of the heightened tensions in the region between the United States of America and Iran. HMS DEFENDER was ready in all respects to protect UK Forces, Allied Forces and our Nations Interests. Fortunately this was not required, however having witnessed the reaction on board from every single member of the Ship’s Company, I have no doubt that we would have been able to deal with any potential threat successfully. Following this we conducted multiple counter-narcotics operations with huge success. Our boarding teams spent busy periods interrogating suspect vessels in the region, which resulted in large amounts of Class A and B narcotics being confiscated and destroyed. The pace of this deployment has been relentless and I have demanded a great deal from the Ship and her crew, to which they have continuously delivered. I believe that only once we have safely returned to Portsmouth and they are enjoying some well earned downtime, will the magnitude of what they have achieved fully sink in. -

Type 45 – Power to Command

Conference Proceedings of EAAW 2 – 3 July 2019 Type 45 – Power to Command Captain J E Voyce* BEng MSc MA CEng MCIPD FIMarEST psc(j) RN Mr R K Wixey BSc(Hons) MSc CEng MIET1 * MoD, UK Synopsis The Royal Navy’s Type 45 Destroyers have been in Service since Jul 10 and have acquired a reputation for being a world class Air Defence asset with power and propulsion (P&P) fragility, that has attracted much positive and negative attention. This paper sets out how a range of circumstances combined in those early years to make the Class unique; a world leading ship not at her full potential. Many of the contributing factors have been discussed in isolation but have not been combined in one paper. The Type 45 has a modest class size of six vessels, yet each ship has the greatest capability ever installed in a Destroyer. It achieved such a punch due to the largest technology step taken in one class, 80% of the equipment on board is new to Royal Navy (RN) Service. And the ambition to use such a potent ship meant that HMS DARING deployed, worldwide, in the quickest time from build of any RN ship since WW2. Simultaneously and with huge dedication from the team, a new support solution was introduced that had the largest Industry involvement the MoD had ever contracted for a Complex Warship. These, and other circumstances created a heady mix in the early part of this decade and this paper will discuss the lessons learnt from an engineering support perspective. -

Uk Carrier Capability Returns to the Indo-Pacific

Center for International Maritime Security (CIMSEC) U.K. CARRIER CAPABILITY RETURNS TO THE INDO-PACIFIC JUNE 14, 2021 By David Scott Toward the end of May 2021, first the Prime Minister, Boris Johnson, and then the Queen visited the British flag ship, the aircraft carrier HMS Queen Elizabeth at Portsmouth. In effect this was their wave-off as, amid much commentary and following much anticipation, the Carrier Strike Group (CSG) set off from Portsmouth for a seven-month long deployment, its first maiden operational deployment. One Australian newspaper ran the headline: “Rule, Britannia! UK deploys carriers to Indo-Pacific.” In April 2021, the British Defense Secretary Ben Wallace set out the aims of the CSG deployment: “It will be flying the flag for Global Britain – projecting our influence, signaling our power, engaging with our friends and reaffirming our commitment to addressing the security challenges of today and tomorrow.” Engaging with friends of course raises the questions of who is not being engaged with, who is not a U.K. friend, and is there any common enemy in sight – all of which points to China. Global Britain reflects this reorientation of a post-Brexit UK away from the European Union and outwards to other parts of the world. It is no surprise that the U.K. is now talking, in its Integrated Review, of a “tilt to the Indo-Pacific,” given the increasing economic weight of this region. This economic shift brings with it a greater focus on sea lane security, protecting commerce flows, and freedom of navigation in international waters. -

Exeter City Council Executive 15 September 2009

EXETER CITY COUNCIL EXECUTIVE 15 SEPTEMBER 2009 AFFILIATION BETWEEN THE CITY OF EXETER AND HMS DEFENDER 1. Purpose of Report 1.1 To consider an opportunity to be one of only two affiliated Cities to HMS Defender, one of the Royal Navy’s latest Type 45 class destroyers. 2. Background 2.1 The City of Exeter has had a long history associated with its affiliation to HMS Exeter which ended with the ship’s decommissioning in May of this year. This affiliation was also much appreciated by the Royal Navy itself which is evidenced by the gifting of one of HMS Exeter’s nameplate to the City. The ship’s Company also extended their right to the Freedom of the City on many occasions, lastly on 25 October 2008 to coincide with Trafalgar Day. 2.2 With this in mind, the City has been approached by the Royal Navy offering it the opportunity to continue its close relationship between the two organisations by becoming one of only two cities that will be affiliated with HMS Defender – the other City being Glasgow. 2.3 HMS Defender will be one of only six type 45 destroyers which will be the largest and most powerful destroyers ever operated by the Royal Navy and the largest general purpose warships (excluding aircraft carriers and amphibious ships) to join its fleet since World War Two cruisers. 2.4 This is considered to be a great honour and recognises the close interest and support given by the City to the Royal Navy. In the words of the offer letter from The First Sea Lord “The Royal Navy values greatly the close interest and support afforded to your previous affiliated ship HMS Exeter; these bonds were developed and wonderfully maintained throughout her life. -

Shared Modular Build of Warships: How a Shared Build Can Support Future Shipbuilding

CHILDREN AND FAMILIES The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit institution that helps improve policy and EDUCATION AND THE ARTS decisionmaking through research and analysis. ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE This electronic document was made available from www.rand.org as a public service INFRASTRUCTURE AND of the RAND Corporation. TRANSPORTATION INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS LAW AND BUSINESS Skip all front matter: Jump to Page 16 NATIONAL SECURITY POPULATION AND AGING PUBLIC SAFETY Support RAND SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY Purchase this document TERRORISM AND Browse Reports & Bookstore HOMELAND SECURITY Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Explore the RAND National Defense Research Institute View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non- commercial use only. Unauthorized posting of RAND electronic documents to a non-RAND website is prohibited. RAND electronic documents are protected under copyright law. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please see RAND Permissions. This product is part of the RAND Corporation technical report series. Reports may include research findings on a specific topic that is limited in scope; present discussions of the methodology employed in research; provide literature reviews, survey instru- ments, modeling exercises, guidelines for practitioners and research professionals, and supporting documentation; or deliver preliminary findings. All RAND reports un- dergo rigorous peer review to ensure that they meet high standards for research quality and objectivity. -

Guns Blazing! Newsletter of the Naval Wargames Society No

All Guns Blazing! Newsletter of the Naval Wargames Society No. 255 – JANUARY 2016 A new website containing a wealth of resources about the Battle of Jutland has been launched by NWS Member, Nick Jellicoe, grandson of Britain's naval commander in 1916, Admiral Sir John Jellicoe. See the excellent “Centenary News” (www.centenarynews.com) for a review of the website. Commemorating both British and German dead, the site is aimed at reaching 'educators, historians and anyone seriously interested in understanding the decisive naval engagement of the First World War.' Animation, interactive displays and podcasts will be used to tell the story of the clash involving almost 250 warships off the Danish North Sea coast on May 31st/June 1st 1916. Another goal is to make the German side of the story better known. Many of the original German accounts of the Battle of Jutland (Skagerraksschlacht) were printed in hard-to-read Gothic text. Optical character recognition software is being used to translate them, but volunteers are also being sought to complete the task and identify more books for translation. http://www.jutland1916.com/#/ http://www.jutland1916.com/blog/latest-news/ 1 The following is an extract from, “The Rise and Fall of the Royal Navy, by Richard Humble. Charles I (1625-1649) authorised the building of Sovereign of the Seas, a magnificent 100 gun three decker “ship of the line” forerunner of every British battle ship built for the next 200 years. Built to the appalling cost of £58,586 16s 9 1/2d (the original estimate of her architect, Phineas Pett had been for £13,000) the Sovereign was fourteen times as costly as Elizabeth I’s “Revenge”. -

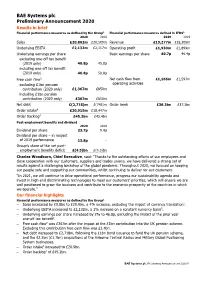

BAE Systems Plc Preliminary Announcement 2020

BAE Systems plc Preliminary Announcement 2020 Results in brief Financial performance measures as defined by the Group1 Financial performance measures defined in IFRS2 2020 2019 2020 2019 Sales £20,862m £20,109m Revenue £19,277m £18,305m Underlying EBITA £2,132m £2,117m Operating profit £1,930m £1,899m Underlying earnings per share Basic earnings per share 40.7p 46.4p excluding one-off tax benefit (2019 only) 46.8p 45.8p including one-off tax benefit (2019 only) 46.8p 50.8p Free cash flow3 Net cash flow from £1,166m £1,597m excluding £1bn pension operating activities contribution (2020 only) £1,367m £850m including £1bn pension contribution (2020 only) £367m £850m Net debt £(2,718)m £(743)m Order book £36.3bn £37.2bn Order intake4 £20,915m £18,447m Order backlog4 £45.2bn £45.4bn Post-employment benefits and dividend 2020 2019 Dividend per share 23.7p 9.4p Dividend per share – in respect of 2019 performance 13.8p - Group’s share of the net post- employment benefits deficit £(4.5)bn £(4.5)bn Charles Woodburn, Chief Executive, said: “Thanks to the outstanding efforts of our employees and close cooperation with our customers, suppliers and trades unions, we have delivered a strong set of results against a challenging backdrop of the global pandemic. Throughout 2020, we focused on keeping our people safe and supporting our communities, whilst continuing to deliver for our customers. “In 2021, we will continue to drive operational performance, progress our sustainability agenda and invest in high-end discriminating technologies to meet our customers’ priorities, which will ensure we are well positioned to grow the business and contribute to the economic prosperity of the countries in which we operate.” Our financial highlights Financial performance measures as defined by the Group1 – Sales increased by £0.8bn to £20.9bn, a 4% increase, excluding the impact of currency translation5.