Individual Action and the Composition of Enemy in Call of Duty: Modern Warfare 1 & 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Call of Duty 1 Instruction Manual

call of duty 1 instruction manual File Name: call of duty 1 instruction manual.pdf Size: 1734 KB Type: PDF, ePub, eBook Category: Book Uploaded: 15 May 2019, 14:26 PM Rating: 4.6/5 from 830 votes. Status: AVAILABLE Last checked: 12 Minutes ago! In order to read or download call of duty 1 instruction manual ebook, you need to create a FREE account. Download Now! eBook includes PDF, ePub and Kindle version ✔ Register a free 1 month Trial Account. ✔ Download as many books as you like (Personal use) ✔ Cancel the membership at any time if not satisfied. ✔ Join Over 80000 Happy Readers Book Descriptions: We have made it easy for you to find a PDF Ebooks without any digging. And by having access to our ebooks online or by storing it on your computer, you have convenient answers with call of duty 1 instruction manual . To get started finding call of duty 1 instruction manual , you are right to find our website which has a comprehensive collection of manuals listed. Our library is the biggest of these that have literally hundreds of thousands of different products represented. Home | Contact | DMCA Book Descriptions: call of duty 1 instruction manual It is requested that this article, or a section of this article, needs to be expanded. Add to the discussion on what needs to be improved, or start your own discussion on the talk page. If you know of a command, but do not see it on the list, feel free to add it in the Commands section, but all coding must be verifiable.Click if you need to know anything about styling a page.Check it out! Check them out! The administrators are the arbitrators, mediators, janitors, and leaders of our wiki, having greater knowledge of wikitext, our policies, and are chosen for neutrality and maturity as well as contributions. -

Monitoring Trends in Global Combat: a New Dataset of Battle Deathsz

European Journal of Population (2005) 21: 145–166 Ó Springer 2005 DOI 10.1007/s10680-005-6851-6 Monitoring Trends in Global Combat: A New Dataset of Battle Deathsz BETHANY LACINA1,2,* and NILS PETTER GLEDITSCH2,3 1Stanford University, Palo Alto, CA, U.S.A.; 2Centre for the Study of Civil War (CSCW), International Peace Research Institute Oslo (PRIO), Hausmanns gate 7, NO-0186 Oslo, Norway; 3Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Trondheim, Norway (*Author for correspondence, e-mail: [email protected]) Received 26 February 2004; accepted in final form 22 June 2004 Lacina, B. and N. P. Gleditsch, 2005, Monitoring Trends in Global Combat: A New Dataset of Battle Deaths, European Journal of Population, 21: 145–166. Abstract. Both academic publications and public media often make inappropriate use of incommensurate conflict statistics, creating misleading impressions about patterns in global warfare. This article clarifies the distinction between combatant deaths, battle deaths, and war deaths. A new dataset of battle deaths in armed conflict is presented for the period 1946–2002. Global battle deaths have been decreasing over most of this period, mainly due to a decline in interstate and internationalised civil armed conflict. It is far more difficult to accurately assess the number of war deaths in conflicts both past and present. But there are compelling reasons to believe that there is a need for increased attention to non-battle causes of mortality, especially displacement and disease in conflict studies. Therefore, it is demographers, public health specialists, and epidemiologists who can best describe the true human cost of many recent armed conflicts and assess the actions necessary to reduce that toll. -

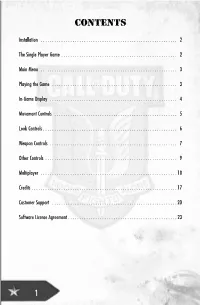

Manual Uscod2.Pdf

CONTENTS Installation . 2 The Single Player Game . 2 Main Menu . 3 Playing the Game . 3 In-Game Display . 4 Movement Controls . 5 Look Controls . 6 Weapon Controls . 7 Other Controls . 9 Multiplayer . 10 Credits . 17 Customer Support . 20 Software License Agreement . 23 1 INSTALLATION Insert Disc One of Call of Duty ® 2 into your CD/DVD-ROM drive. After a few seconds, the Autorun Menu will appear. Click Install to begin the installation process and follow the on-screen instructions. If the Autorun Menu does not appear, you may have Autorun disabled. Double-click on the My Computer icon on your desktop. Open the CD/DVD-ROM drive where the Call of Duty 2 CD/DVD is located. Double-click on Setup.exe to launch the Installer. If you need more information, please consult the Help files. Enter Key Code To install and run the game, you must have a valid Key Code. Your unique Key Code is located on the back of the manual that came with your game. During installation, please enter the Key Code exactly as it appears on the manual. Keep your copy of the Key Code safe and private in case you need to reinstall the game in the future. No one from Activision® or Infinity Ward will ever ask you for your Key Code. Never give your Key Code to anyone. If you lose your Key Code, you will not be issued another one. • Keep your Key Code in a safe, private place in case you need to reinstall your game at a later point. -

WIC Manual FE.Indd

Table of Contents Getting Started . 2 Installation . 2 Enter CD Key . 2 System Requirements . 2 Recommended System Requirements . 2 Updates and Patches . 3 Troubleshooting . 3 Introduction . 3 The Cold War . 3 The Soviet Attack . 3 The Factions . 4 USA . 4 USSR . 4 NATO . 4 Playing the Game . 5 The Roles . 9 Armor . 9 Air . 9 Infantry . 9 Support . 9 The Interface . 10 The Head-Up Display . 10 The Requests Menu . 13 The Mega Map. 14 Massgate . 16 The Menus . 16 The Units . 18 Armor . 18 Air . 20 Infantry . 22 Troop Transport . 24 Support . 25 Tactical Aids . 28 Non-destructive . 28 Selective Strikes . 28 Indiscriminate Strikes. 29 Credits . 31 Massive Entertainment . 31 Sierra Entertainment . 33 Limited Warranty . 37 Technical Support . 38 Hotkeys . Back Cover 1 WWICIC mmanualanual FFE.inddE.indd 1 66/08/07/08/07 112:56:032:56:03 GETTING STARTED Installation Before you install the game, make sure that your computer has the latest hardware drivers installed. Old drivers can stop the game from working properly. Insert the World in Confl ict™ DVD into your DVD-ROM drive. The autorun screen will appear automatically. Click the INSTALL button, and follow the on-screen instructions. At the beginning of the installation process, you are prompted to install DirectX® 9.0c (if you do not already have DirectX® 9.0c or higher). DirectX® 9.0c is required in order to run the game. If the installation program doesn’t appear automatically, double-click the My Computer icon on the Desktop, then double-click on the DVD-ROM drive that contains the game DVD. -

Does Video Gaming Have Impacts on the Brain: Evidence from a Systematic Review

brain sciences Review Does Video Gaming Have Impacts on the Brain: Evidence from a Systematic Review 1, , 2,3, 2,4 Denilson Brilliant T. * y, Rui Nouchi y and Ryuta Kawashima 1 Department of Biomedicine, Indonesia International Institute for Life Sciences (i3L), East Jakarta 13210, Indonesia 2 Smart Ageing Research Center (SARC), Tohoku University, Sendai 980-8575, Japan; [email protected] (R.N.); [email protected] (R.K.) 3 Department of Cognitive Health Science, Institute of Development, Aging and Cancer (IDAC), Tohoku University, Sendai 980-8575, Japan 4 Department of Functional Brain Imaging, Institute of Development, Aging and Cancer (IDAC), Tohoku University, Sendai 980-8575, Japan * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +62-21-29567888 D.B.T. and R.N. contributed equally to this work. y Received: 18 August 2019; Accepted: 23 September 2019; Published: 25 September 2019 Abstract: Video gaming, the experience of playing electronic games, has shown several benefits for human health. Recently, numerous video gaming studies showed beneficial effects on cognition and the brain. A systematic review of video gaming has been published. However, the previous systematic review has several differences to this systematic review. This systematic review evaluates the beneficial effects of video gaming on neuroplasticity specifically on intervention studies. Literature research was conducted from randomized controlled trials in PubMed and Google Scholar published after 2000. A systematic review was written instead of a meta-analytic review because of variations among participants, video games, and outcomes. Nine scientific articles were eligible for the review. Overall, the eligible articles showed fair quality according to Delphi Criteria. -

Playing the Second World War: Call of Duty and the Telling of History Harrison Gish Eludamos

Vol. 4, No. 2 (2010) http://www.eludamos.org Playing the Second World War: Call of Duty and the Telling of History Harrison Gish Eludamos. Journal for Computer Game Culture. 2010; 4 (2), p. 167-180 Playing the Second World War: Call of Duty and the Telling of History HARRISON GISH In a recent episode of The Simpsons (31 January 2010), the crotchety, aged Mr. Burns stands in front of a Nintendo Wii display at the Springfield Mall. Holding the Wii controller as one would hold a handgun, the tycoon finds himself playing a World War II-era first-person shooter that requires him to fire upon members of the approaching German army. Leaning over to his ever-vigilant assistant, Smithers, the somewhat bewildered Burns intones, “Shooting at Nazis...? That’s not how I remember it.” The historical first-person shooter, which this episode of The Simpsons lampoons, has become a conspicuous and highly lucrative sub-genre within contemporary videogames.1 The first-person shooter has always been indebted to skewed representations of World War II, with the genre’s popular genesis closely tied to id Software’s release of Wolfenstein 3D in 1992 (in the game, the player attempts to escape a Nazi-controlled castle in the heart of the Third Reich).2 In the eighteen years since Wolfenstein’s release, numerous iterations of the first-person shooter have appeared, many set in dystopian futuristic worlds such as the decimated cityscapes of Half-Life 2 (Valve 2004) and the alien planet of Halo (Bungie 2001). Games such as Wolfenstein and Battlefield 1942 (Digital Illusions 2002), in contrast, situate game play within war torn European countries during the mid-twentieth century, differentiating themselves as a distinct sub-genre through their evocation of the past. -

Intro by the Admin

The Sierra Chest Newsletter: Issue 2, May 2009 Intro by the admin Dear Sierra fans, Another busy month of construction on the Sierra Chest. Most notably “Gabriel Knight 3: Blood of the Sacred, Blood of the Damned” has been inserted. And while that took far more time than expected, the result is great! More info about that on the next page. We also worked a bit on King’s Quest, and fully inserted “Lost in Time” by Coktel Vision. Some general stuff, such as a load of box arts have been added and it is now also possible to access the fanbased Empire Earth servers through the Chest. Also our friends at UnityHQ, member of the Sierra Gateway and fanbased home of the No One Lives Forever forums and servers, have a small request for you. It is a pleasure to say that, after some 200 uploaded videos on the Sierra Chest’s Youtube channel over the past half a year, we finally nailed an honor! The video “Gabriel Knight 3: Fiction versus Reality” was among the most watched videos in the video gaming category in France on April 26th. It was a small honor, which lasted only a day, but it was an honor nonetheless, so it is gratifying to see things are beginning to fall in the public spotlight. The video combines real locations with Gabriel Knight 3 gameplay and then shifts towards the vampire story during the 2nd half of the video, all guided by music of W. A. Mozart’s Requiem. With the number of subscribers to the Sierra Chest Youtube channel increasing by about 50% over the past month alone, we are confident more fans will find their way to the site and the Sierra Gateway forums (http://www.sierraforums.com). -

Keep Us Safe a Project to Introduce the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child to 8-13 Year-Olds P R /9

Keep Us Safe A project to introduce the UN Convention on The Rights of the Child to 8-13 year-olds p R /9 The UNICEF-UK Protection HRE/CHILD/ Save the Children Y Articles This book is one of three designed to introduce the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child to 8 -13 year olds, and deals with those Articles which cover PROTECTION of the child from abuse and exploitation. “No child will realize its maximum potential and contribution to a better tomorrow if it is forced to be a grown-up for sheer animal survival. A child should crawl because it is the normal préludé to walking, not an escape from conflict or apartheid, not because its legs are too maimed to walk, not because it is too hungry to walk, not because it is paralysed with fear of brutality! A child should play and grow in the perpétuai spring of childhood that recognizes no winter, storm or status of parentage. This is the fundamental and universal right of ail children! The child’s mind is innocent, fresh, clean and free to take in the world in ail its aspects, to challenge it and make it a better place.” Ms. Sally Mugabe, First Lady of Zimbabwe in an address to the National Conférence on the Future United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, Alexandria, Egypt, November 1988 The sériés has been produced, in collaboration, by: UNICEF-UK Save the Children and Oxford Development Education Unit ISBN 1 871440 05 X (UNICEF-UK) ISBN1 87032219 3 (SCF) Copyright: SCF/UNICEF-UK1990 This material may be photocopied for use in schools. -

Students Salute Snow

Minnesota State University Moorhead RED: a Repository of Digital Collections The Advocate Student Newspapers 11-17-2011 The Advocate, November 17, 2011 Minnesota State University Moorhead Follow this and additional works at: https://red.mnstate.edu/advocate Recommended Citation Minnesota State University Moorhead, "The Advocate, November 17, 2011" (2011). The Advocate. 271. https://red.mnstate.edu/advocate/271 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Newspapers at RED: a Repository of Digital Collections. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Advocate by an authorized administrator of RED: a Repository of Digital Collections. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE online at www.msumadvocate.com Advo Eats’ battle of the burgers, Page 7 Thursday, November 17, 2011DVOCATE A MSUM’s weekly student newspaper Moorhead, Minn. Vol. 41 Issue 11 Anthropology Students salute snow club holds clothing drive BY CHARLY HALEY [email protected] The Dragon Anthropological Association is reaching out to the Pine Ridge Oglala Lakota of Pine Ridge, S.D., with a winter clothing drive this month. “We’re collecting new or gently used outerwear. So that’s coats, hats, gloves — for any sizes really, infant to adult,” said Katie Jacobson, vice president and senior anthropology major with an emphasis in archaeology. The collection bins are located in the anthropology main office, King 104. This is the first fundraiser done by the anthropological association, which has been an official student organization for three years. “We thought, OK, it’s time for us to do some kind of fundraiser to help people out,” Jacobson said. -

![Download Call of Duty 2 Full Version for Windows Call of Duty 2 [Cracked] (RELOADED Repack) + Crack Only](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2915/download-call-of-duty-2-full-version-for-windows-call-of-duty-2-cracked-reloaded-repack-crack-only-2042915.webp)

Download Call of Duty 2 Full Version for Windows Call of Duty 2 [Cracked] (RELOADED Repack) + Crack Only

download call of duty 2 full version for windows Call of Duty 2 [Cracked] (RELOADED Repack) + Crack Only. Call of Duty 2 [Cracked] (RELOADED Repack) + Crack Only … Call of Duty 2 is a first-person shooter video game developed by Infinity Ward and published by Activision in most regions of the world. It is the second installment of the Call of Duty series. Announced by Activision on April 7, 2005, the game was released on October 25, 2005 for Microsoft Windows, and on November 22, 2005 as a launch title for the Xbox 360. Other versions were eventually released for OS X, mobile phones, and Pocket PCs. The game is set during World War II and the campaign mode is experienced through the perspectives of four soldiers: one in the Red Army, one in the United States Army, and two in the British Army. It contains four individual campaigns, split into three stories, with a total of 27 missions. Many features were added and changed from the original Call of Duty, notably regenerating health and an icon that indicates a nearby grenade about to explode. Free Download Call of Duty 2 Cracked and Crack Only. World War II greatly influenced the construction of the new world we face. This war destroyed Foxim’s story forever and strengthened the supremacy of liberalism. The Call of Duty game series has already given a lot of maneuver to the Second World War, and when the world of video games was not as good as it is now, with Call of Duty 2, it started a great adventure in the heart of a great war. -

Andersen Article

From America’s Army to Call of Duty: Doing Battle with the Military Entertainment Complex Robin Andersen and Marin Kurti This paper explores the collaboration between the Pentagon and the entertainment industries at the site of the popular interactive format, the war-themed video game. The commercial media in- dustry is heavily invested in the research and development of digital technologies used to create simulations, graphics, and virtual worlds, which are also essential to the networked proto- cols of military training and weapons systems. In addition, video games such as America’s Army have been developed by the United States Armed Forces as recruitment tools. With advances in digital computer-based technologies, war- themed games make increasing claims to realism, authenticity and historical accuracy. Real war footage is frequently inserted into narratives and battlefield sequences. We compare the narra- tives of the experiences of gamers to narratives of recruits and soldier’s experiences of war. Though war themed interactive games are taking simulated battlefields to higher levels of real- ism, including more intense graphic violence, the thrilling excite- ment of entertainment replaces the emotional truth of war, a trend with highly negative consequences. On August 18, 2007, 90 veterans and active duty service mem- bers stood in front of an America's Army game booth in St. Louis in company formation and “sounded off” with the chant, "War is not a game." Their protest was part of a “truth in recruiting” campaign organized by Iraqi Veterans Against the War.1 ar-themed video games, a significant sector of the interactive enter- tainment industry, command attention because of the variety of pro- vocative issues raised by the history of their development and the W trajectory of their uses. -

Extreme+ V2.9

Quick Setup Guide eXtreme+ v2.9 eXtreme+ Support Crew Guy http://www.patmansan.com http://www.mycallofduty.com Copyright © 2013 (document version 2014.02-2.9-1) Legal Stuff Individuals or organizations may utilize the information in this document for the sole purpose of evaluation and guidance. No part of this document may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical or otherwise, including photocopying and recording, for any purpose, without written permission by the eXtreme+ Support Crew. The information contained in this document is provided "AS IS" without any warranty of any kind. Unless otherwise expressly agreed in writing, the eXtreme+ Support Crew makes no warranty as to the value or accuracy of information contained herein. The document could include technical inaccuracies or typographical errors. Changes are periodically added to the information herein. Therefore the eXtreme+ Support Crew reserves the right, without prior notice, to make any change or improvement in the specifications data and information herein, at any time. THE EXTREME+ SUPPORT CREW HEREBY DISCLAIMS ALL WARRANTIES AND CONDITIONS WITH REGARD TO THE INFORMATION CONTAINED HEREIN, INCLUDING ALL IMPLIED WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTABILITY, FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE, TITLE AND NON-INFRINGEMENT. IN NO EVENT SHALL THE EXTREME+ SUPPORT CREW BE LIABLE, WHETHER IN CONTRACT, TORT OR OTHERWISE, FOR ANY INDIRECT, SPECIAL OR CONSEQUENTIAL DAMAGES OR ANY DAMAGES WHATSOEVER INCLUDING BUT NOT LIMITED TO DAMAGES RESULTING FROM LOSS OF USE, DATA, PROFITS, REVENUES, OR CUSTOMERS, ARISING OUT OF OR IN CONNECTION WITH THE USE OR PERFORMANCE OF INFORMATION CONTAINED IN THIS DOCUMENT. Call of Duty ® is a registered trademark of Activision.