The Space-Image : Interactivity and Spatiality of Computer Games

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Discussion on Application for Interior Space Design and the Application of Interior Design Style

3rd International Conference on Education, Management and Computing Technology (ICEMCT 2016) Discussion on Application for Interior Space Design and the Application of Interior Design Style Xiaodong Zhang Institute of Environmental art design, Hebei Institute of Fine Art, Shijiazhuang hebei, 050700, China Keywords: interior design, psychological space, design style Abstract. Interior design is the essence of the interior space design, including physical space design and psychological space design two levels. Interior design style is an important issue for interior designers and owners. Through analysis and Research on the relationships between design and interior design style of interior space, summed up the "interior space design to create a style of interior design" and "interior design style shape the psychological space two obvious characteristics. Interior Space Design and Its Content The Meaning of Interior Space Design. Interior space design is a creative activity of human transformation of living space, through the interior space design can make human living environment become more comfortable [1]. Although the "interior space design" theory is not a long time, but has been constantly being human practice. Since ancient times, human beings have been in the pursuit of the security of living space. Full, comfortable and beautiful. People in the primitive society in the cave laying leaves, weeds and skins and in the walls of the cave with color drawing lines and patterns, and so on for living space transformation, which all belong to the indoor space design. Interior space design is not only focused on solving the relationship between people and nature, but also more and more focus on solving the problem of the relationship between people and society, so that people in the community better work and life. -

Geometric Modeling in Shape Space

Geometric Modeling in Shape Space Martin Kilian Niloy J. Mitra Helmut Pottmann Vienna University of Technology Figure 1: Geodesic interpolation and extrapolation. The blue input poses of the elephant are geodesically interpolated in an as-isometric- as-possible fashion (shown in green), and the resulting path is geodesically continued (shown in purple) to naturally extend the sequence. No semantic information, segmentation, or knowledge of articulated components is used. Abstract space, line geometry interprets straight lines as points on a quadratic surface [Berger 1987], and the various types of sphere geometries We present a novel framework to treat shapes in the setting of Rie- model spheres as points in higher dimensional space [Cecil 1992]. mannian geometry. Shapes – triangular meshes or more generally Other examples concern kinematic spaces and Lie groups which straight line graphs in Euclidean space – are treated as points in are convenient for handling congruent shapes and motion design. a shape space. We introduce useful Riemannian metrics in this These examples show that it is often beneficial and insightful to space to aid the user in design and modeling tasks, especially to endow the set of objects under consideration with additional struc- explore the space of (approximately) isometric deformations of a ture and to work in more abstract spaces. We will show that many given shape. Much of the work relies on an efficient algorithm to geometry processing tasks can be solved by endowing the set of compute geodesics in shape spaces; to this end, we present a multi- closed orientable surfaces – called shapes henceforth – with a Rie- resolution framework to solve the interpolation problem – which mannian structure. -

Analyzing Space Dimensions in Video Games

SBC { Proceedings of SBGames 2019 | ISSN: 2179-2259 Art & Design Track { Full Papers Analyzing Space Dimensions in Video Games Leandro Ouriques Geraldo Xexéo Eduardo Mangeli Programa de Engenharia de Sistemas e Programa de Engenharia de Sistemas e Programa de Engenharia de Sistemas e Computação, COPPE/UFRJ Computação, COPPE/UFRJ Computação, COPPE/UFRJ Center for Naval Systems Analyses Departamento de Ciência da Rio de Janeiro, Brazil (CASNAV), Brazilian Nay Computação, IM/UFRJ E-mail: [email protected] Rio de Janeiro, Brazil Rio de Janeiro, Brazil E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Abstract—The objective of this work is to analyze the role of types of game space without any visualization other than space in video games, in order to understand how game textual. However, in 2018, Matsuoka et al. presented a space affects the player in achieving game goals. Game paper on SBGames that analyzes the meaning of the game spaces have evolved from a single two-dimensional screen to space for the player, explaining how space commonly has huge, detailed and complex three-dimensional environments. significance in video games, being bound to the fictional Those changes transformed the player’s experience and have world and, consequently, to its rules and narrative [5]. This encouraged the exploration and manipulation of the space. led us to search for a better understanding of what is game Our studies review the functions that space plays, describe space. the possibilities that it offers to the player and explore its characteristics. We also analyze location-based games where This paper is divided in seven parts. -

Chapter 6: Design and Design Frameworks: Investing in KBC and Economic Performance

323 | DESIGN AND DESIGN FRAMEWORKS: INVESTMENT IN KBC AND ECONOMIC PERFORMANCE CHAPTER 6. DESIGN AND DESIGN FRAMEWORKS: INVESTMENT IN KBC AND ECONOMIC PERFORMANCE This chapter addresses the nature and the economic impact of design by looking at design-related intellectual property and how businesses protect their knowledge based capital. The chapter reviews the nature and various definitions of design and how design-related IP, specifically registered designs, relates to other formal IP mechanisms such as patents, trademarks, and copyright. It looks at the primary areas of design activity in a subset of OECD countries and investigates the similarities and differences of the constituent design IP regimes as well as the various treaties governing international design IP regulation. The review continues with an examination of how design-related IP functions in comparison to and in conjunction with other formal and informal IP protection mechanisms and what factors motivate firms to choose and appropriate combinations of protection mechanisms. By examining historical patterns of design registrations in a variety of ways, this chapter identifies trends, at the national level, of how firms perceive the importance of design-related IP. Analysis of national origins of registrations in both the European Community and the United States provides an indicator of the activity of those countries’ businesses relative to their proximities to the markets. It explores the existence of possible alternative indicators for design activity and of industry-specific variations across the sample set. The chapter concludes with a review of input and output measures as stated in the limited set of studies that have endeavoured to establish or quantify the value and/or benefit of design and design-related IP. -

Intelligent Design Creationism and the Constitution

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Washington University St. Louis: Open Scholarship Washington University Law Review Volume 83 Issue 1 2005 Is It Science Yet?: Intelligent Design Creationism and the Constitution Matthew J. Brauer Princeton University Barbara Forrest Southeastern Louisiana University Steven G. Gey Florida State University Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_lawreview Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, Education Law Commons, First Amendment Commons, Religion Law Commons, and the Science and Technology Law Commons Recommended Citation Matthew J. Brauer, Barbara Forrest, and Steven G. Gey, Is It Science Yet?: Intelligent Design Creationism and the Constitution, 83 WASH. U. L. Q. 1 (2005). Available at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_lawreview/vol83/iss1/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington University Law Review by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Washington University Law Quarterly VOLUME 83 NUMBER 1 2005 IS IT SCIENCE YET?: INTELLIGENT DESIGN CREATIONISM AND THE CONSTITUTION MATTHEW J. BRAUER BARBARA FORREST STEVEN G. GEY* TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT ................................................................................................... 3 INTRODUCTION.................................................................................................. -

Monitoring Trends in Global Combat: a New Dataset of Battle Deathsz

European Journal of Population (2005) 21: 145–166 Ó Springer 2005 DOI 10.1007/s10680-005-6851-6 Monitoring Trends in Global Combat: A New Dataset of Battle Deathsz BETHANY LACINA1,2,* and NILS PETTER GLEDITSCH2,3 1Stanford University, Palo Alto, CA, U.S.A.; 2Centre for the Study of Civil War (CSCW), International Peace Research Institute Oslo (PRIO), Hausmanns gate 7, NO-0186 Oslo, Norway; 3Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Trondheim, Norway (*Author for correspondence, e-mail: [email protected]) Received 26 February 2004; accepted in final form 22 June 2004 Lacina, B. and N. P. Gleditsch, 2005, Monitoring Trends in Global Combat: A New Dataset of Battle Deaths, European Journal of Population, 21: 145–166. Abstract. Both academic publications and public media often make inappropriate use of incommensurate conflict statistics, creating misleading impressions about patterns in global warfare. This article clarifies the distinction between combatant deaths, battle deaths, and war deaths. A new dataset of battle deaths in armed conflict is presented for the period 1946–2002. Global battle deaths have been decreasing over most of this period, mainly due to a decline in interstate and internationalised civil armed conflict. It is far more difficult to accurately assess the number of war deaths in conflicts both past and present. But there are compelling reasons to believe that there is a need for increased attention to non-battle causes of mortality, especially displacement and disease in conflict studies. Therefore, it is demographers, public health specialists, and epidemiologists who can best describe the true human cost of many recent armed conflicts and assess the actions necessary to reduce that toll. -

An Overview of the Building Delivery Process

An Overview of the Building Delivery CHAPTER Process 1 (How Buildings Come into Being) CHAPTER OUTLINE 1.1 PROJECT DELIVERY PHASES 1.11 CONSTRUCTION PHASE: CONTRACT ADMINISTRATION 1.2 PREDESIGN PHASE 1.12 POSTCONSTRUCTION PHASE: 1.3 DESIGN PHASE PROJECT CLOSEOUT 1.4 THREE SEQUENTIAL STAGES IN DESIGN PHASE 1.13 PROJECT DELIVERY METHOD: DESIGN- BID-BUILD METHOD 1.5 CSI MASTERFORMAT AND SPECIFICATIONS 1.14 PROJECT DELIVERY METHOD: 1.6 THE CONSTRUCTION TEAM DESIGN-NEGOTIATE-BUILD METHOD 1.7 PRECONSTRUCTION PHASE: THE BIDDING 1.15 PROJECT DELIVERY METHOD: CONSTRUCTION DOCUMENTS MANAGEMENT-RELATED METHODS 1.8 PRECONSTRUCTION PHASE: THE SURETY BONDS 1.16 PROJECT DELIVERY METHOD: DESIGN-BUILD METHOD 1.9 PRECONSTRUCTION PHASE: SELECTING THE GENERAL CONTRACTOR AND PROJECT 1.17 INTEGRATED PROJECT DELIVERY METHOD DELIVERY 1.18 FAST-TRACK PROJECT SCHEDULING 1.10 CONSTRUCTION PHASE: SUBMITTALS AND CONSTRUCTION PROGRESS DOCUMENTATION Building construction is a complex, significant, and rewarding process. It begins with an idea and culminates in a structure that may serve its occupants for several decades, even centuries. Like the manufacturing of products, building construction requires an ordered and planned assembly of materials. It is, however, far more complicated than product manufacturing. Buildings are assembled outdoors by a large number of diverse constructors and artisans on all types of sites and are subject to all kinds of weather conditions. Additionally, even a modest-sized building must satisfy many performance criteria and legal constraints, requires an immense variety of materials, and involves a large network of design and production firms. Building construction is further complicated by the fact that no two buildings are identical; each one must be custom built to serve a unique function and respond to its specific context and the preferences of its owner, user, and occupant. -

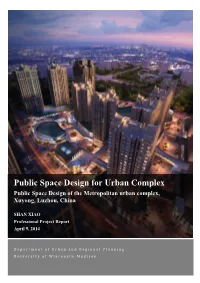

Public Space Design for Urban Complex Public Space Design of the Metropolitan Urban Complex, Xuyong, Luzhou, China

Public Space Design for Urban Complex Public Space Design of the Metropolitan urban complex, Xuyong, Luzhou, China SHAN XIAO Professional Project Report April 9, 2014 D e p a r t m e n t of Urban and Regional Planning University of Wisconsin - M a d i s o n CCC Executive Summary I choose this project as a continuity of what I did during the internship last summer. It’s a large-scale urban design project; I cooperated with the project team to come up with an urban design sketch, I took the responsibility of the public space design of the Metropolitan urban complex. I begin this paper by asking myself as planners, as urban designers, what can we do to make the public space attractive, comfortable, and at the same time support and reflect the attributes of the urban complex? In search of the answers, I did extensive literature readings and researches to explore the fundamental principles of landscape and environmental design of urban complex. I also did plenty of case studies of excellent public space design to learn practical techniques designers employed when doing an actual project. Through studying, I concluded several principles that are particularly worth noting, such as designs should be people oriented and commerce oriented, should be integrated into larger cultural context and urban texture, and should shape a sense of place. Bases on these guidelines, I developed my public space design for the Metropolitan urban complex in Xuyong, Luzhou, China. I used Photoshop, CAD, Sketchup to come up with the final deliverables. I finished this report with acknowledgement of the significance of architectural environment, and conclusions of schemes to improve the environment during the design process. -

Does Intelligent Design Postulate a “Supernatural Creator?” Overview: No

Truth Sheet # 09-05 Does intelligent design postulate a “supernatural creator?” Overview: No. The ACLU, and many of its expert witnesses, have alleged that teaching the scientific theory of intelligent design (ID) is unconstitutional in all circumstances because it posits a “supernatural creator.” Yet actual statements from intelligent design theorists have made it clear that the scientific theory of intelligent design does not address metaphysical and religious questions such as the nature or identity of the designer. Firstly, the textbook being used in Dover, Of Pandas and People (Pandas ), makes it clear that design theory does not address religious or metaphysical questions, such as the nature or identity of the designer. Consider these two clear disclaimers from Pandas : "[T]he intelligent design explanation has unanswered questions of its own. But unanswered questions, which exist on both sides, are an essential part of healthy science; they define the areas of needed research. Questions often expose hidden errors that have impeded the progress of science. For example, the place of intelligent design in science has been troubling for more than a century. That is because on the whole, scientists from within Western culture failed to distinguish between intelligence, which can be recognized by uniform sensory experience, and the supernatural, which cannot. Today we recognize that appeals to intelligent design may be considered in science, as illustrated by current NASA search for extraterrestrial intelligence (SETI). Archaeology has pioneered the development of methods for distinguishing the effects of natural and intelligent causes. We should recognize, however, that if we go further, and conclude that the intelligence responsible for biological origins is outside the universe (supernatural) or within it, we do so without the help of science." 1 “[T]he concept of design implies absolutely nothing about beliefs normally associated with Christian fundamentalism, such as a young earth, a global flood, or even the existence of the Christian God. -

Personal Space: Interior Design Approaches to Bedrooms in Mental Health Developments 2

Personal Space: Interior design approaches to bedrooms in mental health developments 2 www.healthierplaces.org 1 Personal Space: Interior design approaches to bedrooms in mental health developments The bedroom is perhaps the most intimate built environment. In a hospital, a bedroom is the one place that is yours for the time you are there; a place to rest in safety, to recover. This takes on a particular significance in mental health settings where bedrooms, though not the primary location for treatment and care, need to be a home from home and your place of refuge. Designing mental health bedrooms that are at the same time safe and pleasant is a real challenge. These small spaces must deliver in a number of areas. They must be: • a place that feels ‘homely’ to people with different needs and preferences, from young people to elderly people with dementia; people who may have very different ideas of what is friendly and reassuring, and what is alienating and strange. • a safe place; allowing observation and, often, meeting anti-ligature requirements in a manner that does not detrimentally effect the ‘homely’ nature and perception of privacy. • a place that is robust; being easy to keep clean and maintained so that it stays nice and healthy and for each occupant, whatever is thrown at it. • a place that is healing; that has the characteristics which evidence based design links to improved recovery times – upto 14% reduction in inpatient stays (Lawson and Phiri (2003)). This design challenge is an issue that is repeated tens of times in any one development, and hundreds of times across the country, thereby representing a significant investment in built infrastructure and the potential to impact care settings and outcomes for a huge number of people who can be resident in these establishments for a significant period of time. -

WIC Manual FE.Indd

Table of Contents Getting Started . 2 Installation . 2 Enter CD Key . 2 System Requirements . 2 Recommended System Requirements . 2 Updates and Patches . 3 Troubleshooting . 3 Introduction . 3 The Cold War . 3 The Soviet Attack . 3 The Factions . 4 USA . 4 USSR . 4 NATO . 4 Playing the Game . 5 The Roles . 9 Armor . 9 Air . 9 Infantry . 9 Support . 9 The Interface . 10 The Head-Up Display . 10 The Requests Menu . 13 The Mega Map. 14 Massgate . 16 The Menus . 16 The Units . 18 Armor . 18 Air . 20 Infantry . 22 Troop Transport . 24 Support . 25 Tactical Aids . 28 Non-destructive . 28 Selective Strikes . 28 Indiscriminate Strikes. 29 Credits . 31 Massive Entertainment . 31 Sierra Entertainment . 33 Limited Warranty . 37 Technical Support . 38 Hotkeys . Back Cover 1 WWICIC mmanualanual FFE.inddE.indd 1 66/08/07/08/07 112:56:032:56:03 GETTING STARTED Installation Before you install the game, make sure that your computer has the latest hardware drivers installed. Old drivers can stop the game from working properly. Insert the World in Confl ict™ DVD into your DVD-ROM drive. The autorun screen will appear automatically. Click the INSTALL button, and follow the on-screen instructions. At the beginning of the installation process, you are prompted to install DirectX® 9.0c (if you do not already have DirectX® 9.0c or higher). DirectX® 9.0c is required in order to run the game. If the installation program doesn’t appear automatically, double-click the My Computer icon on the Desktop, then double-click on the DVD-ROM drive that contains the game DVD. -

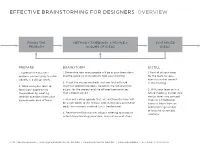

Effective Brainstorming for Designers Overview

EFFECTIVE BRAINSTORMING FOR DESIGNERS OVERVIEW FOCUS THE METHOD + TIMEBOXES x PEOPLE = SYNTHESIZE PROBLEM VOLUME OF IDEAS IDEAS PREPARE BRAINSTORM DISTILL 1. Agree on the business 1. Determine how many people will be in your brainstorm, 1. Post all of your ideas problem you’re trying to solve and the space you’ll be able to hold your meeting. for the team to see— (ideally in a design brief). even those that weren’t 2. Select the design methods that you feel will yield in the meeting. 2. Work with your team to the most appropriate ideas, based on the required final focus your approach to output for the project and the different personalities 2. With your team or in a the problem by creating that will be involved. future meeting, cluster your ideation questions from your design ideas into concept agreed-upon area of focus. 3. Plan out a clear agenda that sets out how the time will maps as a timeboxed be used—down to the minute, with stated idea generation exercise. Move from an goals for everyone involved (a.k.a. timeboxing). overwhelming number of ideas to systematic 4. Reserve the final minutes of your meeting to establish solutions. criteria for evaluating your ideas and outline next steps. ©2012 DAVID SHERWIN | [email protected] | CHANGEORDERBLOG.COM | @CHANGEORDER | ALL RIGHTS RESERVED PREPARING FOR A BRAINSTORM: IDEATION QUESTIONS Let’s start coming up with all sorts of amazing ideas! Wait—where do we even start? First, jot down some ideation questions. They are restatements of issues that form the basis of a design problem.