Water Quality and Wastewater

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wastewater Technology Fact Sheet: Ammonia Stripping

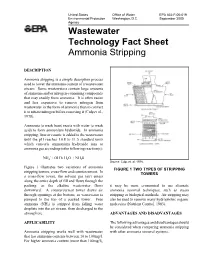

United States Office of Water EPA 832-F-00-019 Environmental Protection Washington, D.C. September 2000 Agency Wastewater Technology Fact Sheet Ammonia Stripping DESCRIPTION Ammonia stripping is a simple desorption process used to lower the ammonia content of a wastewater stream. Some wastewaters contain large amounts of ammonia and/or nitrogen-containing compounds that may readily form ammonia. It is often easier and less expensive to remove nitrogen from wastewater in the form of ammonia than to convert it to nitrate-nitrogen before removing it (Culp et al., 1978). Ammonia (a weak base) reacts with water (a weak acid) to form ammonium hydroxide. In ammonia stripping, lime or caustic is added to the wastewater until the pH reaches 10.8 to 11.5 standard units which converts ammonium hydroxide ions to ammonia gas according to the following reaction(s): + - NH4 + OH 6 H2O + NH38 Source: Culp, et. al, 1978. Figure 1 illustrates two variations of ammonia FIGURE 1 TWO TYPES OF STRIPPING stripping towers, cross-flow and countercurrent. In TOWERS a cross-flow tower, the solvent gas (air) enters along the entire depth of fill and flows through the packing, as the alkaline wastewater flows it may be more economical to use alternate downward. A countercurrent tower draws air ammonia removal techniques, such as steam through openings at the bottom, as wastewater is stripping or biological methods. Air stripping may pumped to the top of a packed tower. Free also be used to remove many hydrophobic organic ammonia (NH3) is stripped from falling water molecules (Nutrient Control, 1983). droplets into the air stream, then discharged to the atmosphere. -

Ozonedisinfection.Pdf

ETI - Environmental Technology Initiative Project funded by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency under Assistance Agreement No. CX824652 What is disinfection? Human exposure to wastewater discharged into the environment has increased in the last 15 to 20 years with the rise in population and the greater demand for water resources for recreation and other purposes. Disinfection of wastewater is done to prevent infectious diseases from being spread and to ensure that water is safe for human contact and the environment. There is no perfect disinfectant. However, there are certain characteristics to look for when choosing the most suitable disinfectant: • Ability to penetrate and destroy infectious agents under normal operating conditions; • Lack of characteristics that could be harmful to people and the environment; • Safe and easy handling, shipping, and storage; • Absence of toxic residuals, such as cancer-causing compounds, after disinfection; and • Affordable capital and operation and maintenance (O&M) costs. What is ozone disinfection? One common method of disinfecting wastewater is ozonation (also known as ozone disinfection). Ozone is an unstable gas that can destroy bacteria and viruses. It is formed when oxygen molecules (O2) collide with oxygen atoms to produce ozone (O3). Ozone is generated by an electrical discharge through dry air or pure oxygen and is generated onsite because it decomposes to elemental oxygen in a short amount of time. After generation, ozone is fed into a down-flow contact chamber containing the wastewater to be disinfected. From the bottom of the contact chamber, ozone is diffused into fine bubbles that mix with the downward flowing wastewater. See Figure 1 on page 2 for a schematic of the ozonation process. -

Introduction to Co2 Chemistry in Sea Water

INTRODUCTION TO CO2 CHEMISTRY IN SEA WATER Andrew G. Dickson Scripps Institution of Oceanography, UC San Diego Mauna Loa Observatory, Hawaii Monthly Average Carbon Dioxide Concentration Data from Scripps CO Program Last updated August 2016 2 ? 410 400 390 380 370 2008; ~385 ppm 360 350 Concentration (ppm) 2 340 CO 330 1974; ~330 ppm 320 310 1960 1965 1970 1975 1980 1985 1990 1995 2000 2005 2010 2015 Year EFFECT OF ADDING CO2 TO SEA WATER 2− − CO2 + CO3 +H2O ! 2HCO3 O C O CO2 1. Dissolves in the ocean increase in decreases increases dissolved CO2 carbonate bicarbonate − HCO3 H O O also hydrogen ion concentration increases C H H 2. Reacts with water O O + H2O to form bicarbonate ion i.e., pH = –lg [H ] decreases H+ and hydrogen ion − HCO3 and saturation state of calcium carbonate decreases H+ 2− O O CO + 2− 3 3. Nearly all of that hydrogen [Ca ][CO ] C C H saturation Ω = 3 O O ion reacts with carbonate O O state K ion to form more bicarbonate sp (a measure of how “easy” it is to form a shell) M u l t i p l e o b s e r v e d indicators of a changing global carbon cycle: (a) atmospheric concentrations of carbon dioxide (CO2) from Mauna Loa (19°32´N, 155°34´W – red) and South Pole (89°59´S, 24°48´W – black) since 1958; (b) partial pressure of dissolved CO2 at the ocean surface (blue curves) and in situ pH (green curves), a measure of the acidity of ocean water. -

National Primary Drinking Water Regulations

National Primary Drinking Water Regulations Potential health effects MCL or TT1 Common sources of contaminant in Public Health Contaminant from long-term3 exposure (mg/L)2 drinking water Goal (mg/L)2 above the MCL Nervous system or blood Added to water during sewage/ Acrylamide TT4 problems; increased risk of cancer wastewater treatment zero Eye, liver, kidney, or spleen Runoff from herbicide used on row Alachlor 0.002 problems; anemia; increased risk crops zero of cancer Erosion of natural deposits of certain 15 picocuries Alpha/photon minerals that are radioactive and per Liter Increased risk of cancer emitters may emit a form of radiation known zero (pCi/L) as alpha radiation Discharge from petroleum refineries; Increase in blood cholesterol; Antimony 0.006 fire retardants; ceramics; electronics; decrease in blood sugar 0.006 solder Skin damage or problems with Erosion of natural deposits; runoff Arsenic 0.010 circulatory systems, and may have from orchards; runoff from glass & 0 increased risk of getting cancer electronics production wastes Asbestos 7 million Increased risk of developing Decay of asbestos cement in water (fibers >10 fibers per Liter benign intestinal polyps mains; erosion of natural deposits 7 MFL micrometers) (MFL) Cardiovascular system or Runoff from herbicide used on row Atrazine 0.003 reproductive problems crops 0.003 Discharge of drilling wastes; discharge Barium 2 Increase in blood pressure from metal refineries; erosion 2 of natural deposits Anemia; decrease in blood Discharge from factories; leaching Benzene -

Water Quality Conditions in the United States a Profile from the 1998 National Water Quality Inventory Report to Congress

United States Office of Water (4503F) EPA841-F-00-006 Environmental Protection Washington, DC 20460 June 2000 Agency Water Quality Conditions in the United States A Profile from the 1998 National Water Quality Inventory Report to Congress States, tribes, territories, and interstate commissions report that, in 1998, about 40% of U.S. streams, lakes, and estuaries that were assessed were not clean enough to support uses such as fishing and swimming. About 32% of U.S. waters were assessed for this national inventory of water quality. Leading pollutants in impaired waters include siltation, bacteria, nutrients, and metals. Runoff from agricultural lands and urban areas are the primary sources of these pollu- tants. Although the United States has made significant progress in cleaning up polluted waters over the past 30 years, much remains to be done to restore and protect the nation’s waters. Findings States also found that 96% of assessed Great Lakes shoreline miles are impaired, primarily due to pollut- Recent water quality data find that more than ants in fish tissue at levels that exceed standards to 291,000 miles of assessed rivers and streams do not protect human health. States assessed 90% of Great meet water quality standards. Across all types of water- Lakes shoreline miles. bodies, states, territories, tribes, and other jurisdictions report that poor water quality affects aquatic life, fish Wetlands are being lost in the contiguous United consumption, swimming, and drinking water. In their States at a rate of about 100,000 acres per year. Eleven 1998 reports, states assessed 840,000 miles of rivers states and tribes listed sources of recent wetland loss; and 17.4 million acres of lakes, including 150,000 conversion for agricultural uses, road construction, and more river miles and 600,000 more lake acres than residential development are leading reasons for loss. -

2021 Water Quality Report

2021 WATER QUALITY REPORT 2021 WATER QUALITY REPORT CITY OF NEWARK: SOUTH WELL FIELD TREATMENT PLANT AIR STRIPPER BUILDING Annual Water Quality Report The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) Newark meets or exceeds the water quality requires public water suppliers to provide standards of the Delaware Division of Public consumer confidence reports (CCR) to their Health Office of Drinking Water and the customers . These reports are also known as Environmental Protection Agency. The tables on annual water quality reports. The below report pages 4-6 of this report list those substances summarizes information regarding the sources found in our finished water during calendar year used (i.e. rivers, reservoirs, or aquifers), any 2020. detected contaminants, compliance and educational efforts. How the Water is Treated The City’s 317 million gallon reservoir provides a Drinking water, including bottled water, may At the Curtis Water Treatment Plant (CWTP), reliable source of raw water which can be treated reasonably be expected to contain at least small water from the White Clay Creek is clarified with and ready for drinking in times of heavy rain or amounts of some substances. The presence of alum and polymer and then filtered to remove drought. In an effort to keep sediment these substances does not necessarily indicate impurities. Chlorine is added to kill harmful accumulation in our water mains to a minimum, that water poses a health risk. In order to ensure bacteria and viruses. Finally, fluoride is added to we flush the entire system yearly. that tap water is safe to drink, the EPA prescribes the water to protect your teeth. -

51. Astrobiology: the Final Frontier of Science Education

www.astrosociety.org/uitc No. 51 - Summer 2000 © 2000, Astronomical Society of the Pacific, 390 Ashton Avenue, San Francisco, CA 94112. Astrobiology: The Final Frontier of Science Education by Jodi Asbell-Clarke and Jeff Lockwood What (or Whom) Are We Looking For? Where Do We Look? Lessons from Our Past The Search Is On What Does the Public Have to Learn from All This? A High School Curriculum in Astrobiology Astrobiology seems to be all the buzz these days. It was the focus of the ASP science symposium this summer; the University of Washington is offering it as a new Ph.D. program, and TERC (Technical Education Research Center) is developing a high school integrated science course based on it. So what is astrobiology? The NASA Astrobiology Institute defines this new discipline as the study of the origin, evolution, distribution, and destiny of life in the Universe. What this means for scientists is finding the means to blend research fields such as microbiology, geoscience, and astrophysics to collectively answer the largest looming questions of humankind. What it means for educators is an engaging and exciting discipline that is ripe for an integrated approach to science education. Virtually every topic that one deals with in high school science is embedded in astrobiology. What (or Whom) Are We Looking For? Movies and television shows such as Contact and Star Trek have teased viewers with the idea of life on other planets and even in other galaxies. Illustration courtesy of and © 2000 by These fictional accounts almost always deal with intelligent beings that have Kathleen L. -

Ammonia in Drinking-Water

WHO/SDE/WSH/03.04/01 English only Ammonia in Drinking-water Background document for development of WHO Guidelines for Drinking-water Quality _______________________ Originally published in Guidelines for drinking-water quality, 2nd ed. Vol. 2. Health criteria and other supporting information. World Health Organization, Geneva, 1996. © World Health Organization 2003 All rights reserved. Publications of the World Health Organization can be obtained from Marketing and Dissemination, World Health Organization, 20 Avenue Appia, 1211 Geneva 27, Switzerland (tel: +41 22 791 2476; fax: +41 22 791 4857; email: [email protected]). Requests for permission to reproduce or translate WHO publications – whether for sale or for noncommercial distribution – should be addressed to Publications, at the above address (fax: +41 22 791 4806; email: [email protected]). The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the World Health Organization concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific companies or of certain manufacturers’ products does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by the World Health Organization in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. Errors and omissions excepted, the names of proprietary products are distinguished by initial capital letters. The World Health Organization does not warrant that the information contained in this publication is complete and correct and shall not be liable for any damages incurred as a result of its use. -

Evaluating Residential Indoor Air Quality Concerns1

Designation: D7297 – 06 Standard Practice for Evaluating Residential Indoor Air Quality Concerns1 This standard is issued under the fixed designation D7297; the number immediately following the designation indicates the year of original adoption or, in the case of revision, the year of last revision. A number in parentheses indicates the year of last reapproval. A superscript epsilon (´) indicates an editorial change since the last revision or reapproval. 1. Scope 2. Referenced Documents 1.1 This standard practice describes procedures for evaluat- 2.1 ASTM Standards:2 ing indoor air quality (IAQ) concerns in residential buildings. D1356 Terminology Relating to Sampling and Analysis of 1.2 The practice primarily addresses IAQ concerns encoun- Atmospheres tered in single-family detached and attached (for example, D1357 Practice for Planning the Sampling of the Ambient townhouse or duplex design) residential buildings. Limited Atmosphere guidance is also included for low- and high-rise multifamily D4861 Practice for Sampling and Selection of Analytical dwellings. Techniques for Pesticides and Polychlorinated Biphenyls 1.3 The IAQ evaluation procedures are comprised of inter- in Air views with the homeowner or resident(s) (including telephone D4947 Test Method for Chlordane and Heptachlor Residues interviews and face-to-face meetings) and on-site investiga- in Indoor Air tions (including walk-through, assessment, and measure- D5197 Test Method for Determination of Formaldehyde ments). For practicality in application, these procedures are and Other Carbonyl Compounds in Air (Active Sampler dividing into three separate phases. Methodology) 1.4 The procedures described in this standard practice are D5438 Practice for Collection of Floor Dust for Chemical aimed at identifying potential causes contributing to the IAQ Analysis concern. -

Origins of Life in the Universe Zackary Johnson

11/4/2007 Origins of Life in the Universe Zackary Johnson OCN201 Fall 2007 [email protected] Zackary Johnson http://www.soest.hawaii.edu/oceanography/zij/education.html Uniiiversity of Hawaii Department of Oceanography Class Schedule Nov‐2Originsof Life and the Universe Nov‐5 Classification of Life Nov‐7 Primary Production Nov‐9Consumers Nov‐14 Evolution: Processes (Steward) Nov‐16 Evolution: Adaptation() (Steward) Nov‐19 Marine Microbiology Nov‐21 Benthic Communities Nov‐26 Whale Falls (Smith) Nov‐28 The Marine Food Web Nov‐30 Community Ecology Dec‐3 Fisheries Dec‐5Global Ecology Dec‐12 Final Major Concepts TIMETABLE Big Bang! • Life started early, but not at the beginning, of Earth’s Milky Way (and other galaxies formed) history • Abiogenesis is the leading hypothesis to explain the beginning of life on Earth • There are many competing theories as to how this happened • Some of the details have been worked out, but most Formation of Earth have not • Abiogenesis almost certainly occurred in the ocean 20‐15 15‐94.5Today Billions of Years Before Present 1 11/4/2007 Building Blocks TIMETABLE Big Bang! • Universe is mostly hydrogen (H) and helium (He); for Milky Way (and other galaxies formed) example –the sun is 70% H, 28% He and 2% all else! Abundance) e • Most elements of interest to biology (C, N, P, O, etc.) were (Relativ 10 produced via nuclear fusion Formation of Earth Log at very high temperature reactions in large stars after Big Bang 20‐13 13‐94.7Today Atomic Number Billions of Years Before Present ORIGIN OF LIFE ON EARTH Abiogenesis: 3 stages Divine Creation 1. -

Diffuse Pollution, Degraded Waters Emerging Policy Solutions

Diffuse Pollution, Degraded Waters Emerging Policy Solutions Policy HIGHLIGHTS Diffuse Pollution, Degraded Waters Emerging Policy Solutions “OECD countries have struggled to adequately address diffuse water pollution. It is much easier to regulate large, point source industrial and municipal polluters than engage with a large number of farmers and other land-users where variable factors like climate, soil and politics come into play. But the cumulative effects of diffuse water pollution can be devastating for human well-being and ecosystem health. Ultimately, they can undermine sustainable economic growth. Many countries are trying innovative policy responses with some measure of success. However, these approaches need to be replicated, adapted and massively scaled-up if they are to have an effect.” Simon Upton – OECD Environment Director POLICY H I GH LI GHT S After decades of regulation and investment to reduce point source water pollution, OECD countries still face water quality challenges (e.g. eutrophication) from diffuse agricultural and urban sources of pollution, i.e. pollution from surface runoff, soil filtration and atmospheric deposition. The relative lack of progress reflects the complexities of controlling multiple pollutants from multiple sources, their high spatial and temporal variability, the associated transactions costs, and limited political acceptability of regulatory measures. The OECD report Diffuse Pollution, Degraded Waters: Emerging Policy Solutions (OECD, 2017) outlines the water quality challenges facing OECD countries today. It presents a range of policy instruments and innovative case studies of diffuse pollution control, and concludes with an integrated policy framework to tackle this challenge. An optimal approach will likely entail a mix of policy interventions reflecting the basic OECD principles of water quality management – pollution prevention, treatment at source, the polluter pays and the beneficiary pays principles, equity, and policy coherence. -

Monitoring Water Quality & Quantity in Mining

SURFACE & GROUNDWATER / ENVIRONMENT & ECOSYSTEMS DHI SOLUTION MONITORING WATER QUALITY & QUANTITY IN MINING Environmental monitoring - tailor-made! ENVIRONMENTAL MONITORING - THE KEY TO KNOWLEDGE SUMMARY Regardless of the project, monitoring is a crucial element of gaining knowledge CLIENT about environmental conditions. When it comes to monitoring water, it is essential The mining industry and associated to do this in an optimal way so as to provide only the necessary information, which companies can be used for specific actions. Too many monitoring programmes have been established with the aim to know everything, which eventually leads to enormous CHALLENGE amount of data but not knowledge. Assessment of water quality and quantity Water is linked to nearly every type of mining industry, whether as groundwater, Collect the right variables surface water coastal water, or process/wastewater and accordingly there is a Fulfill the regulations substantial need to assess water quality and quantity conditions in all phases of Ensure scientifically sound judgement of mining: exploration, operation/production and decommissioning. impacts We at DHI work with tailor-made monitoring, which enables the client to get all the SOLUTION relevant data - and only those. To provide tailor-made monitoring based on the relevant data Changes in water quality can Applying state-of-the-art technologies as lead to many types of impacts part of the monitoring and the mining industry unfortunately creates various VALUE such problems. One of the Optimisation of monitoring costs standard impacts comes from Fast delivery of data acid drainage of the mines or Easier compliance with permits the mine-tailing and has multiple impacts on not just the biology but also on water which is taken downstream for domestic or industrial use.