Introduction to Co2 Chemistry in Sea Water

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chemical Equilibrium Chemistry (H) 1St Year SEM-II, Dated: 7Th April 2020

Remarks of Assignment 2: Chemical Equilibrium Chemistry (H) 1st Year SEM-II, Dated: 7th April 2020 Grades: A (Excellent); B+ (Very good); B (Good) and C (Poor) S. NAME Roll No. Grade Remarks No. 1. Sejal Jain 1931210 Resubmission: Not submitted or misplaced 2. Harshita 1931206 A In Q.6. no need to discuss the situations, according to figure 1 it is NO and Q.8. Try to write concisely 3. Yogesh Kumar 1931152 B+ Q. 6. Not correct 4. Pooja 1931132 B+ Q. 6. Not correct 5. Riddhima 120 A Excellent 6. Jyoti 112 B+ Q. 6. Not correct 7. Vivek 146 B+ Q. 6. Not correct 8. Vikash 154 B+ Q. 6. Not correct 9. Nidhi 150 A Excellent 10. Mehak Vaish 136 B+ Q. 6. Not correct 11. Rinka* 122 B+ Q. 6. Not correct 12. Sheenu 202 A Excellent 13. Bhupendra 104 B+ Q. 6. Not correct Maurya 14. Deepanshu 142 B+ Q. 6. Not correct 15. Diksha Rathi 204 A Excellent 16. Khushboo Mittal 256 A Q. 6. Not correct 17. Amit Patwa 252 B+ Q. 6. Not correct 18. Aman Tomar 246 A Excellent 19. Vinay Sharma 176 B+ Q. 6. Not correct 20. Garima Nveen 128 B+ Q. 6. Not correct and Q. 8. Answer in terms of number of moles, 21. Yatin Kumar 254 B+ Q. 6. Not correct 22. Ajay Kumar 238 B+ Q. 6. Not correct 23. Divya Yadav 214 A Excellent, Kindly check Q.6. not properly scanned but I think you want to say NO 24. Kushagra Malik 174 B+ Q. -

Wastewater Technology Fact Sheet: Ammonia Stripping

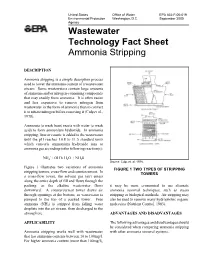

United States Office of Water EPA 832-F-00-019 Environmental Protection Washington, D.C. September 2000 Agency Wastewater Technology Fact Sheet Ammonia Stripping DESCRIPTION Ammonia stripping is a simple desorption process used to lower the ammonia content of a wastewater stream. Some wastewaters contain large amounts of ammonia and/or nitrogen-containing compounds that may readily form ammonia. It is often easier and less expensive to remove nitrogen from wastewater in the form of ammonia than to convert it to nitrate-nitrogen before removing it (Culp et al., 1978). Ammonia (a weak base) reacts with water (a weak acid) to form ammonium hydroxide. In ammonia stripping, lime or caustic is added to the wastewater until the pH reaches 10.8 to 11.5 standard units which converts ammonium hydroxide ions to ammonia gas according to the following reaction(s): + - NH4 + OH 6 H2O + NH38 Source: Culp, et. al, 1978. Figure 1 illustrates two variations of ammonia FIGURE 1 TWO TYPES OF STRIPPING stripping towers, cross-flow and countercurrent. In TOWERS a cross-flow tower, the solvent gas (air) enters along the entire depth of fill and flows through the packing, as the alkaline wastewater flows it may be more economical to use alternate downward. A countercurrent tower draws air ammonia removal techniques, such as steam through openings at the bottom, as wastewater is stripping or biological methods. Air stripping may pumped to the top of a packed tower. Free also be used to remove many hydrophobic organic ammonia (NH3) is stripped from falling water molecules (Nutrient Control, 1983). droplets into the air stream, then discharged to the atmosphere. -

Ozonedisinfection.Pdf

ETI - Environmental Technology Initiative Project funded by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency under Assistance Agreement No. CX824652 What is disinfection? Human exposure to wastewater discharged into the environment has increased in the last 15 to 20 years with the rise in population and the greater demand for water resources for recreation and other purposes. Disinfection of wastewater is done to prevent infectious diseases from being spread and to ensure that water is safe for human contact and the environment. There is no perfect disinfectant. However, there are certain characteristics to look for when choosing the most suitable disinfectant: • Ability to penetrate and destroy infectious agents under normal operating conditions; • Lack of characteristics that could be harmful to people and the environment; • Safe and easy handling, shipping, and storage; • Absence of toxic residuals, such as cancer-causing compounds, after disinfection; and • Affordable capital and operation and maintenance (O&M) costs. What is ozone disinfection? One common method of disinfecting wastewater is ozonation (also known as ozone disinfection). Ozone is an unstable gas that can destroy bacteria and viruses. It is formed when oxygen molecules (O2) collide with oxygen atoms to produce ozone (O3). Ozone is generated by an electrical discharge through dry air or pure oxygen and is generated onsite because it decomposes to elemental oxygen in a short amount of time. After generation, ozone is fed into a down-flow contact chamber containing the wastewater to be disinfected. From the bottom of the contact chamber, ozone is diffused into fine bubbles that mix with the downward flowing wastewater. See Figure 1 on page 2 for a schematic of the ozonation process. -

Hydrothermal Vents. Teacher's Notes

Hydrothermal Vents Hydrothermal Vents. Teacher’s notes. A hydrothermal vent is a fissure in a planet's surface from which geothermally heated water issues. They are usually volcanically active. Seawater penetrates into fissures of the volcanic bed and interacts with the hot, newly formed rock in the volcanic crust. This heated seawater (350-450°) dissolves large amounts of minerals. The resulting acidic solution, containing metals (Fe, Mn, Zn, Cu) and large amounts of reduced sulfur and compounds such as sulfides and H2S, percolates up through the sea floor where it mixes with the cold surrounding ocean water (2-4°) forming mineral deposits and different types of vents. In the resulting temperature gradient, these minerals provide a source of energy and nutrients to chemoautotrophic organisms that are, thus, able to live in these extreme conditions. This is an extreme environment with high pressure, steep temperature gradients, and high concentrations of toxic elements such as sulfides and heavy metals. Black and white smokers Some hydrothermal vents form a chimney like structure that can be as 60m tall. They are formed when the minerals that are dissolved in the fluid precipitates out when the super-heated water comes into contact with the freezing seawater. The minerals become particles with high sulphur content that form the stack. Black smokers are very acidic typically with a ph. of 2 (around that of vinegar). A black smoker is a type of vent found at depths typically below 3000m that emit a cloud or black material high in sulphates. White smokers are formed in a similar way but they emit lighter-hued minerals, for example barium, calcium and silicon. -

National Primary Drinking Water Regulations

National Primary Drinking Water Regulations Potential health effects MCL or TT1 Common sources of contaminant in Public Health Contaminant from long-term3 exposure (mg/L)2 drinking water Goal (mg/L)2 above the MCL Nervous system or blood Added to water during sewage/ Acrylamide TT4 problems; increased risk of cancer wastewater treatment zero Eye, liver, kidney, or spleen Runoff from herbicide used on row Alachlor 0.002 problems; anemia; increased risk crops zero of cancer Erosion of natural deposits of certain 15 picocuries Alpha/photon minerals that are radioactive and per Liter Increased risk of cancer emitters may emit a form of radiation known zero (pCi/L) as alpha radiation Discharge from petroleum refineries; Increase in blood cholesterol; Antimony 0.006 fire retardants; ceramics; electronics; decrease in blood sugar 0.006 solder Skin damage or problems with Erosion of natural deposits; runoff Arsenic 0.010 circulatory systems, and may have from orchards; runoff from glass & 0 increased risk of getting cancer electronics production wastes Asbestos 7 million Increased risk of developing Decay of asbestos cement in water (fibers >10 fibers per Liter benign intestinal polyps mains; erosion of natural deposits 7 MFL micrometers) (MFL) Cardiovascular system or Runoff from herbicide used on row Atrazine 0.003 reproductive problems crops 0.003 Discharge of drilling wastes; discharge Barium 2 Increase in blood pressure from metal refineries; erosion 2 of natural deposits Anemia; decrease in blood Discharge from factories; leaching Benzene -

Major Ions, Carbonate System, Alkalinity, Ph (Kalff Chapters 13 and 14) A. Major Ions 1. Common Ions There Are 7 Common Ions I

Major Ions, Carbonate System, Alkalinity, pH (Kalff Chapters 13 and 14) A. Major ions 1. Common Ions There are 7 common ions in freshwater: (e.g. Table 13-3, p207) +2 +2 +1 +1 cations: Ca , Mg , Na , K -1 -2 -1 anions: Cl , SO4 , HCO3 +1 -1 In some surface waters, other ionic species are sometimes important (e.g. NH4 , F , organic acids, etc.), but in most cases the 7 ions listed above are the only ions present in significant concentration. In addition to the common ions, OH-1 and H+1 are important species because of the dissociation of water itself. In freshwater, the total concentration of ions and the relative abundance of each are highly variable, reflecting the influence of precipitation (rain), weathering and evaporation. In contrast to freshwater, the world ocean is very uniform (Table 13-6, p214). The total concentration of ions varies only slightly, depending on local advection of freshwater from major rivers and regions of surplus rainfall or evaporation. For “standard” seawater, with “chlorinity” = 19.000 parts per thousand, the following concentrations are observed for the common ions. (Similar ratios are available for nearly the entire periodic table, although at lower concentrations.) These fixed ratios in the sea are the result of the “constancy of composition” of seawater. Ion parts per thousand (g/kg) - - - Cl 18.980 (the definition of "clorinity" includes Br , I , etc.) + Na 10.556 -2 SO4 2.649 +2 Mg 1.272 +2 Ca 0.400 + K 0.380 - HCO3 0.140 Br- 0.065 2. Sources of ions in freshwater a. -

Sea-Level Rise for the Coasts of California, Oregon, and Washington: Past, Present, and Future

Sea-Level Rise for the Coasts of California, Oregon, and Washington: Past, Present, and Future As more and more states are incorporating projections of sea-level rise into coastal planning efforts, the states of California, Oregon, and Washington asked the National Research Council to project sea-level rise along their coasts for the years 2030, 2050, and 2100, taking into account the many factors that affect sea-level rise on a local scale. The projections show a sharp distinction at Cape Mendocino in northern California. South of that point, sea-level rise is expected to be very close to global projections; north of that point, sea-level rise is projected to be less than global projections because seismic strain is pushing the land upward. ny significant sea-level In compliance with a rise will pose enor- 2008 executive order, mous risks to the California state agencies have A been incorporating projec- valuable infrastructure, devel- opment, and wetlands that line tions of sea-level rise into much of the 1,600 mile shore- their coastal planning. This line of California, Oregon, and study provides the first Washington. For example, in comprehensive regional San Francisco Bay, two inter- projections of the changes in national airports, the ports of sea level expected in San Francisco and Oakland, a California, Oregon, and naval air station, freeways, Washington. housing developments, and sports stadiums have been Global Sea-Level Rise built on fill that raised the land Following a few thousand level only a few feet above the years of relative stability, highest tides. The San Francisco International Airport (center) global sea level has been Sea-level change is linked and surrounding areas will begin to flood with as rising since the late 19th or to changes in the Earth’s little as 40 cm (16 inches) of sea-level rise, a early 20th century, when climate. -

3-D Surface Visualization of Ph Titration “Topos”: Equivalence Point Cliffs, Dilution Ramps and Buffer Plateaus

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Water Topos: A 3-D Trend Surface Approach to Viewing and Teaching Aqueous Equilibrium Open Educational Resources (OER) Chemistry 11-2020 Chapter 1.1: 3-D Surface Visualization of pH Titration “Topos”: Equivalence Point Cliffs, Dilution Ramps and Buffer Plateaus Garon C. Smith University of Montana, Missoula Md Mainul Hossain North South University, Bangladesh Patrick MacCarthy Colorado School of Mines Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/topos Part of the Chemistry Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Smith, Garon C.; Hossain, Md Mainul; and MacCarthy, Patrick, "Chapter 1.1: 3-D Surface Visualization of pH Titration “Topos”: Equivalence Point Cliffs, Dilution Ramps and Buffer Plateaus" (2020). Water Topos: A 3-D Trend Surface Approach to Viewing and Teaching Aqueous Equilibrium Chemistry. 2. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/topos/2 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Open Educational Resources (OER) at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Water Topos: A 3-D Trend Surface Approach to Viewing and Teaching Aqueous Equilibrium Chemistry by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Part 1: Acid-Base Equilibrium Chapter 1.1 3-D Surface Visualization of pH Titration “Topos”: Equivalence Point Cliffs, Dilution Ramps and Buffer Plateaus Garon C. Smith1, Md Mainul Hossain2 and Patrick MacCarthy3 1Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, The University of Montana, Missoula, MT 59812, Department of Biochemistry and Microbiology, North South University, Dhaka, Bangladesh, and 2Department of Chemistry and Geochemistry, Colorado School of Mines, Golden, CO 80401 Abstract 3-D topographic surfaces (“topos”) can be generated to visualize how pH behaves during titration and dilution procedures. -

51. Astrobiology: the Final Frontier of Science Education

www.astrosociety.org/uitc No. 51 - Summer 2000 © 2000, Astronomical Society of the Pacific, 390 Ashton Avenue, San Francisco, CA 94112. Astrobiology: The Final Frontier of Science Education by Jodi Asbell-Clarke and Jeff Lockwood What (or Whom) Are We Looking For? Where Do We Look? Lessons from Our Past The Search Is On What Does the Public Have to Learn from All This? A High School Curriculum in Astrobiology Astrobiology seems to be all the buzz these days. It was the focus of the ASP science symposium this summer; the University of Washington is offering it as a new Ph.D. program, and TERC (Technical Education Research Center) is developing a high school integrated science course based on it. So what is astrobiology? The NASA Astrobiology Institute defines this new discipline as the study of the origin, evolution, distribution, and destiny of life in the Universe. What this means for scientists is finding the means to blend research fields such as microbiology, geoscience, and astrophysics to collectively answer the largest looming questions of humankind. What it means for educators is an engaging and exciting discipline that is ripe for an integrated approach to science education. Virtually every topic that one deals with in high school science is embedded in astrobiology. What (or Whom) Are We Looking For? Movies and television shows such as Contact and Star Trek have teased viewers with the idea of life on other planets and even in other galaxies. Illustration courtesy of and © 2000 by These fictional accounts almost always deal with intelligent beings that have Kathleen L. -

Causes of Sea Level Rise

FACT SHEET Causes of Sea OUR COASTAL COMMUNITIES AT RISK Level Rise What the Science Tells Us HIGHLIGHTS From the rocky shoreline of Maine to the busy trading port of New Orleans, from Roughly a third of the nation’s population historic Golden Gate Park in San Francisco to the golden sands of Miami Beach, lives in coastal counties. Several million our coasts are an integral part of American life. Where the sea meets land sit some of our most densely populated cities, most popular tourist destinations, bountiful of those live at elevations that could be fisheries, unique natural landscapes, strategic military bases, financial centers, and flooded by rising seas this century, scientific beaches and boardwalks where memories are created. Yet many of these iconic projections show. These cities and towns— places face a growing risk from sea level rise. home to tourist destinations, fisheries, Global sea level is rising—and at an accelerating rate—largely in response to natural landscapes, military bases, financial global warming. The global average rise has been about eight inches since the centers, and beaches and boardwalks— Industrial Revolution. However, many U.S. cities have seen much higher increases in sea level (NOAA 2012a; NOAA 2012b). Portions of the East and Gulf coasts face a growing risk from sea level rise. have faced some of the world’s fastest rates of sea level rise (NOAA 2012b). These trends have contributed to loss of life, billions of dollars in damage to coastal The choices we make today are critical property and infrastructure, massive taxpayer funding for recovery and rebuild- to protecting coastal communities. -

Marine Pollution: a Critique of Present and Proposed International Agreements and Institutions--A Suggested Global Oceans' Environmental Regime Lawrence R

Hastings Law Journal Volume 24 | Issue 1 Article 5 1-1972 Marine Pollution: A Critique of Present and Proposed International Agreements and Institutions--A Suggested Global Oceans' Environmental Regime Lawrence R. Lanctot Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_law_journal Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Lawrence R. Lanctot, Marine Pollution: A Critique of Present and Proposed International Agreements and Institutions--A Suggested Global Oceans' Environmental Regime, 24 Hastings L.J. 67 (1972). Available at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_law_journal/vol24/iss1/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hastings Law Journal by an authorized editor of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. Marine Pollution: A Critique of Present and Proposed International Agreements and Institutions-A Suggested Global Oceans' Environmental Regime By LAWRENCE R. LANCTOT* THE oceans are earth's last significant frontier for man's utiliza- tion. Advances in marine technology are opening previously unreach- able depths to permit the study of the oceans' mysteries and the extrac- tion of valuable natural resources.' Because these vast resources were inaccessible in the past, international law does not provide any certain rules governing the ownership and development of marine resources which lie beyond the limits of national jurisdiction.2 In response to this legal uncertainty and in the face of accelerating technology, the United Nations General Assembly has called a General Conference on the Law of the Sea in 1973 to formulate international conventions gov- erning the development of the seabed and ocean floor., Great interest * J.D., University of San Francisco, 1968; LL.M., Columbia University, 1969; Adjunct Professor of Law, University of San Francisco. -

Natural Variability of the Arctic Ocean Sea Ice During the Present Interglacial

Natural variability of the Arctic Ocean sea ice during the present interglacial Anne de Vernala,1, Claude Hillaire-Marcela, Cynthia Le Duca, Philippe Robergea, Camille Bricea, Jens Matthiessenb, Robert F. Spielhagenc, and Ruediger Steinb,d aGeotop-Université du Québec à Montréal, Montréal, QC H3C 3P8, Canada; bGeosciences/Marine Geology, Alfred Wegener Institute Helmholtz Centre for Polar and Marine Research, 27568 Bremerhaven, Germany; cOcean Circulation and Climate Dynamics Division, GEOMAR Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research, 24148 Kiel, Germany; and dMARUM Center for Marine Environmental Sciences and Faculty of Geosciences, University of Bremen, 28334 Bremen, Germany Edited by Thomas M. Cronin, U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, VA, and accepted by Editorial Board Member Jean Jouzel August 26, 2020 (received for review May 6, 2020) The impact of the ongoing anthropogenic warming on the Arctic such an extrapolation. Moreover, the past 1,400 y only encom- Ocean sea ice is ascertained and closely monitored. However, its pass a small fraction of the climate variations that occurred long-term fate remains an open question as its natural variability during the Cenozoic (7, 8), even during the present interglacial, on centennial to millennial timescales is not well documented. i.e., the Holocene (9), which began ∼11,700 y ago. To assess Here, we use marine sedimentary records to reconstruct Arctic Arctic sea-ice instabilities further back in time, the analyses of sea-ice fluctuations. Cores collected along the Lomonosov Ridge sedimentary archives is required but represents a challenge (10, that extends across the Arctic Ocean from northern Greenland to 11). Suitable sedimentary sequences with a reliable chronology the Laptev Sea were radiocarbon dated and analyzed for their and biogenic content allowing oceanographical reconstructions micropaleontological and palynological contents, both bearing in- can be recovered from Arctic Ocean shelves, but they rarely formation on the past sea-ice cover.