Americans' Attitudes About Science and Technology: the Social Context for Public Communication

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

I Used to Be Antifa Gabriel Nadales

I Used to be Antifa Gabriel Nadales There was a time in my life when I was angry, bitter, and deeply unhappy. I wanted to lash out at the whole “fascist” system—the greedy, heartless power structure that didn’t care about me or the rest of society’s innocent victims, a system that had robbed, beaten and stolen from my ancestors. The whole corrupt edifice deserved to be brought down, reduced to rubble. I was a perfect recruit for Antifa, the left-wing group which claims to fight against fascism. And so, I became a member. Now I was one of those who had the guts to fight against “the fascists” who were exploiting disadvantaged people. I wasn’t a ‘card-carrying’ antifascist—there is no such thing as an official Antifa membership. But I was ready at a moment’s notice to slip on the black mask and march in what Antifa calls “the black bloc”—a cadre of other black-clad Antifa members— to taunt police and destroy property. Antifa stands for “antifascist,” but that’s purposefully deceptive. For one thing, the very name is calibrated so that anyone who dares to criticize the group or its tactics can be labeled “fascist.” This allows Antifa to justify violence against all who dare stand up or speak out against them. A few groups boldly declare themselves Antifa, like “Rose City Antifa” in Portland. But most don’t, preferring to avoid the negative publicity. That’s part of Antifa’s appeal—and strength: It’s hard to pin down. -

Our 2020 Form

PUBLIC DISCLOSURE COPY Return of Organization Exempt From Income Tax OMB No. 1545-0047 Form 990 Under section 501(c), 527, or 4947(a)(1) of the Internal Revenue Code (except private foundations) 2020 a Department of the Treasury Do not enter social security numbers on this form as it may be made public. Open to Public Internal Revenue Service a Go to www.irs.gov/Form990 for instructions and the latest information. Inspection A For the 2020 calendar year, or tax year beginning , 2020, and ending , 20 B Check if applicable: C Name of organization LEADERSHIP INSTITUTE D Employer identification number Address change Doing business as 51-0235174 Name change Number and street (or P.O. box if mail is not delivered to street address) Room/suite E Telephone number Initial return 1101 N HIGHLAND STREET (703) 247-2000 Final return/terminated City or town, state or province, country, and ZIP or foreign postal code Amended return ARLINGTON, VA 22201 G Gross receipts $ 24,354,691 Application pending F Name and address of principal officer: MORTON BLACKWELL H(a) Is this a group return for subordinates? Yes ✔ No SAME AS C ABOVE H(b) Are all subordinates included? Yes No I Tax-exempt status: 501(c)(3) 501(c) ( ) ` (insert no.) 4947(a)(1) or 527 If “No,” attach a list. See instructions J Website: a WWW.LEADERSHIPINSTITUTE.ORG H(c) Group exemption number a K Form of organization: Corporation Trust Association Other a L Year of formation: 1979 M State of legal domicile: VA Part I Summary 1 Briefly describe the organization’s mission or most significant activities: EDUCATE PEOPLE FOR SUCCESSFUL PARTICIPATION IN GOVERNMENT, POLITICS AND MEDIA. -

Spring 2013 COME Volume 14 Number 3

the Flame The Magazine of Claremont Graduate University Spring 2013 COME Volume 14 Number 3 The Flame is published by Claremont Graduate University 150 East Tenth Street Claremont, California 91711 ©2013 by Claremont Graduate BACK TO University Director of University Communications Esther Wiley Managing Editor Brendan Babish CAMPUS Art Director Shari Fournier-O’Leary News Editor Rod Leveque Online Editor WITHOUT Sheila Lefor Editorial Contributors Mandy Bennett Dean Gerstein Kelsey Kimmel Kevin Riel LEAVING Emily Schuck Rachel Tie Director of Alumni Services Monika Moore Distribution Manager HOME Mandy Bennett Every semester CGU holds scores of lectures, performances, and other events Photographers Marc Campos on our campus. Jonathan Gibby Carlos Puma On Claremont Graduate University’s YouTube channel you can view the full video of many William Vasta Tom Zasadzinski of our most notable speakers, events, and faculty members: www.youtube.com/cgunews. Illustration Below is just a small sample of our recent postings: Thomas James Claremont Graduate University, founded in 1925, focuses exclusively on graduate-level study. It is a member of the Claremont Colleges, Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, distinguished professor of psychology in CGU’s School of a consortium of seven independent Behavioral and Organizational Sciences, talks about why one of the great challenges institutions. to positive psychology is to help keep material consumption within sustainable limits. President Deborah A. Freund Executive Vice President and Provost Jacob Adams Jack Scott, former chancellor of the California Community Colleges, and Senior Vice President for Finance Carl Cohn, member of the California Board of Education, discuss educational and Administration politics in California, with CGU Provost Jacob Adams moderating. -

Climate Change: How Do We Know We're Not Wrong? Naomi Oreskes

Changing Planet: Past, Present, Future Lecture 4 – Climate Change: How Do We Know We’re Not Wrong? Naomi Oreskes, PhD 1. Start of Lecture Four (0:16) [ANNOUNCER:] From the Howard Hughes Medical Institute...The 2012 Holiday Lectures on Science. This year's lectures: "Changing Planet: Past, Present, Future," will be given by Dr. Andrew Knoll, Professor of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology at Harvard University; Dr. Naomi Oreskes, Professor of History and Science Studies at the University of California, San Diego; and Dr. Daniel Schrag, Professor of Earth and Planetary Sciences at Harvard University. The fourth lecture is titled: Climate Change: How Do We Know We're Not Wrong? And now, a brief video to introduce our lecturer Dr. Naomi Oreskes. 2. Profile of Dr. Naomi Oreskes (1:14) [DR. ORESKES:] One thing that's really important for all people to understand is that the whole notion of certainty is mistaken, and it's something that climate skeptics and deniers and the opponents of evolution really exploit. Many of us think that scientific knowledge is certain, so therefore if someone comes along and points out the uncertainties in a certain scientific body of knowledge, we think that undermines the science, we think that means that there's a problem in the science, and so part of my message is to say that that view of science is incorrect, that the reality of science is that it's always uncertain because if we're actually doing research, it means that we're asking questions, and if we're asking questions, then by definition we're asking questions about things we don't already know about, so uncertainty is part of the lifeblood of science, it's something we need to embrace and realize it's a good thing, not a bad thing. -

“Hard-Won” Consensus Brent Ranalli

Ranalli • Climate SCienCe, ChaRaCteR, and the “haRd-Won” ConSenSuS Brent Ranalli Climate Science, Character, and the “Hard-Won” Consensus ABSTRACT: What makes a consensus among scientists credible and convincing? This paper introduces the notion of a “hard-won” consensus and uses examples from recent debates over climate change science to show that this heuristic stan- dard for evaluating the quality of a consensus is widely shared. The extent to which a consensus is “hard won” can be understood to depend on the personal qualities of the participating experts; the article demonstrates the continuing util- ity of the norms of modern science introduced by Robert K. Merton by showing that individuals on both sides of the climate science debate rely intuitively on Mertonian ideas—interpreted in terms of character—to frame their arguments. INTRodUCTIoN he late Michael Crichton, science fiction writer and climate con- trarian, once remarked: “Whenever you hear the consensus of Tscientists agrees on something or other, reach for your wallet, because you’re being had. In science consensus is irrelevant. What is relevant is reproducible results” (Crichton 2003). Reproducibility of results and other methodological criteria are indeed the proper basis for scientific judgments. But Crichton is wrong to say that consensus is irrel- evant. Consensus among scientists serves to certify facts for the lay public.1 Those on the periphery of the scientific enterprise (i.e., policy makers and the public), who don’t have the time or the expertise or the equipment to check results for themselves, necessarily rely on the testimony of those at the center. -

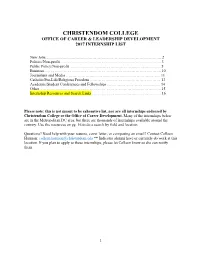

INTERNSHIP RESOURCES and HELPFUL SEARCH LINKS These Sites Allow You to Do Advanced Searches for Internships Nationwide

CHRISTENDOM COLLEGE OFFICE OF CAREER & LEADERSHIP DEVELOPMENT 2017 INTERNSHIP LIST New Jobs…………………………………………………………………………….. 2 Politics/Non-profit…………………………………………………………………... 3 Public Policy/Non-profit …………………………………………………………... 5 Business……………………………………………………………………………... 10 Journalism and Media ……………………………………………………………… 11 Catholic/Pro-Life/Religious Freedom ……………………………………………… 13 Academic/Student Conferences and Fellowships ………………………………….. 14 Other ………………………………………………………………………………... 15 Internship Resources and Search Links …………………………………………….. 16 Please note: this is not meant to be exhaustive list, nor are all internships endorsed by Christendom College or the Office of Career Development. Many of the internships below are in the Metropolitan DC area, but there are thousands of internships available around the country. Use the resources on pg. 16 to do a search by field and location. Questions? Need help with your resume, cover letter, or composing an email? Contact Colleen Harmon: [email protected] ** Indicates alumni have or currently do work at this location. If you plan to apply to these internships, please let Colleen know so she can notify them. 1 NEW JOBS! National Journalism Center- summer deadline March 20 The National Journalism Center, a project of Young America's Foundation, provides aspiring conservative and libertarian journalists with the premier opportunity to learn the principles and practice of responsible reporting. The National Journalism Center combines 12 weeks of on-the- job training at a Washington, D.C.-based media outlet and once-weekly training seminars led by prominent journalists, policy experts, and NJC faculty. The program matches interns with print, broadcast, or online media outlets based on their interests and experience. Interns spend 30 hours/week gaining practical, hands-on journalism experience. Potential placements include The Washington Times, The Washington Examiner, CNN, Fox News Channel, and more. -

Vincent Russo Represents Clients on a Diverse Set of Legal and Public Policy Matters

Vincent Russo represents clients on a diverse set of legal and public policy matters. He was previously the Executive Counsel to Georgia Secretaries of State Brian Kemp and Karen Handel from 2008 to 2014, and served as the Assistant Commissioner of Securities in Georgia. Vincent currently serves as campaign counsel to Kemp for Governor and is Chief Deputy General Counsel to the Georgia Republican Party. Vincent has over a decade of legal, regulatory, and policy experience in Georgia, including in the areas of financial services, professional licensing, tax, real estate, elections, and procurement. He has worked on legislation involving the Georgia Civil Practice Act, the Georgia Business Corporations Code, the Georgia Election Code, the Georgia Uniform Securities Act, the Vincent Revised Georgia Trust Code, several professional licensing boards, and investment tax credits. In 2011 and 2012, Vincent oversaw and was Russo instrumental in the comprehensive overhaul of Georgia’s securities [email protected] regulations while serving as the Assistant Commissioner of Securities. Phone: 404-856-3260 Vincent brings a profound understanding of the pivotal relationship between government, business, and the law to his clients. As a litigator, Vincent represents clients in an array of business disputes, shareholder actions, real estate litigation, and administrative proceedings. He also advises clients bidding on government contracts, including representing them in procurement disputes. Because of his experience in both the public and private sector, Vincent is able to develop strategic plans to achieve his clients’ legislative, regulatory, and policy objectives at all levels of government, and provide direct advocacy with key government decision-makers on issues critical to his clients. -

The Consensus on Anthropogenic Global Warming Matters

BSTXXX10.1177/0270467617707079Bulletin of Science, Technology & SocietyPowell 707079research-article2017 Article Bulletin of Science, Technology & Society 2016, Vol. 36(3) 157 –163 The Consensus on Anthropogenic © The Author(s) 2017 Reprints and permissions: sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav Global Warming Matters DOI:https://doi.org/10.1177/0270467617707079 10.1177/0270467617707079 journals.sagepub.com/home/bst James Lawrence Powell1 Abstract Skuce et al., responding to Powell, title their article, “Does It Matter if the Consensus on Anthropogenic Global Warming Is 97% or 99.99%?” I argue that the extent of the consensus does matter, most of all because scholars have shown that the stronger the public believe the consensus to be, the more they support the action on global warming that human society so desperately needs. Moreover, anyone who knows that scientists once thought that the continents are fixed in place, or that the craters of the Moon are volcanic, or that the Earth cannot be more than 100 million years old, understands that a small minority has sometimes turned out to be right. But it is hard to think of a case in the modern era in which scientists have been virtually unanimous and wrong. Moreover, as I show, the consensus among publishing scientists is demonstrably not 97%. Instead, five surveys of the peer-reviewed literature from 1991 to 2015 combine to 54,195 articles with an average consensus of 99.94%. Keywords global warming, climate change, consensus, peer review, history of science Introduction Consensus Skuce et al. (2016, henceforth S16), responding to Powell What does consensus in science mean and how can it best be (2016), ask, “Does it matter if the consensus on anthropo- measured? The Oxford English Dictionary (2016) defines genic global warming is 97% or 99.99%?” consensus as “Agreement in opinion; the collective unani- Of course it matters. -

Perceptions of Science in America

PERCEPTIONS OF SCIENCE IN AMERICA A REPORT FROM THE PUBLIC FACE OF SCIENCE INITIATIVE THE PUBLIC FACE OF SCIENCE PERCEPTIONS OF SCIENCE IN AMERICA american academy of arts & sciences Cambridge, Massachusetts © 2018 by the American Academy of Arts & Sciences All rights reserved. isbn: 0-87724-120-1 This publication is available online at http://www.publicfaceofscience.org. The views expressed in this publication are those held by the contributors and are not necessarily those of the Officers and Members of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Please direct inquiries to: American Academy of Arts & Sciences 136 Irving Street Cambridge ma 02138-1996 Telephone: 617-576-5000 Fax: 617-576-5050 Email: [email protected] Web: www.amacad.org CONTENTS Preface v Top Three Takeaways vii Introduction 1 SECTION 1: General Perceptions of Science 4 Confidence in Scientific Leaders Remains Relatively Stable 4 A Majority of Americans Views Scientific Research as Beneficial . 6 . But Many are Concerned about the Pace of Change 7 Americans Express Strong Support for Public Investment in Research 8 Americans Support an Active Role for Science and Scientists in Public Life 10 Scientists Should Play a Major Role in Shaping Public Policy 11 Discussion and Research Considerations 12 SECTION 2: Demographic Influences on General Views of Science 14 Confidence in Scientific Leaders Varies Based on Demographics and Other Factors 14 Higher Educational Attainment Correlates with Positive Perceptions of Science 16 Trust in Scientists Varies Based on Education and Politics 18 Discussion and Research Considerations 20 SECTION 3: Case Studies of Perceptions on Specific Science Topics 22 There is No Single Anti-Science Population . -

Download File

Tow Center for Digital Journalism CONSERVATIVE A Tow/Knight Report NEWSWORK A Report on the Values and Practices of Online Journalists on the Right Anthony Nadler, A.J. Bauer, and Magda Konieczna Funded by the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation. Table of Contents Executive Summary 3 Introduction 7 Boundaries and Tensions Within the Online Conservative News Field 15 Training, Standards, and Practices 41 Columbia Journalism School Conservative Newswork 3 Executive Summary Through much of the 20th century, the U.S. news diet was dominated by journalism outlets that professed to operate according to principles of objectivity and nonpartisan balance. Today, news outlets that openly proclaim a political perspective — conservative, progressive, centrist, or otherwise — are more central to American life than at any time since the first journalism schools opened their doors. Conservative audiences, in particular, express far less trust in mainstream news media than do their liberal counterparts. These divides have contributed to concerns of a “post-truth” age and fanned fears that members of opposing parties no longer agree on basic facts, let alone how to report and interpret the news of the day in a credible fashion. Renewed popularity and commercial viability of openly partisan media in the United States can be traced back to the rise of conservative talk radio in the late 1980s, but the expansion of partisan news outlets has accelerated most rapidly online. This expansion has coincided with debates within many digital newsrooms. Should the ideals journalists adopted in the 20th century be preserved in a digital news landscape? Or must today’s news workers forge new relationships with their publics and find alternatives to traditional notions of journalistic objectivity, fairness, and balance? Despite the centrality of these questions to digital newsrooms, little research on “innovation in journalism” or the “future of news” has explicitly addressed how digital journalists and editors in partisan news organizations are rethinking norms. -

GORDON DAKOTA ARNOLD [email protected] EDUCATION

GORDON DAKOTA ARNOLD [email protected] EDUCATION Hillsdale College Hillsdale, MI Ph.D. in Politics Expected May 2023 Regent University Virginia Beach, VA B.A. in Government, Minor in History August 2013 to May 2017 FOREIGN LANGUAGES Latin Reading Competency TEACHING EXPERIENCE Regent University Academic Support Center Virginia Beach, VA Writing Tutor August 2016 to May 2017 May 2019 to June 2020 Tutored undergraduate and graduate students to better organize, stylize, and format academic writing projects by delineating linguistic rules for clarity, concision, grace, and grammar. RESEARCH EXPERIENCE Hillsdale College Hillsdale, MI Graduate Faculty Research Assistant August 2018 to May 2020 Assisted Hillsdale political scientists in their scholarship by transcribing lectures and editing drafts of their written scholarship. Hillsdale College Hillsdale, MI Library Archivist August 2020 to Present Assists the library in logging and transcribing information from the letters and essays of Harry V. Jaffa and other scholars affiliated with Hillsdale College. PUBLICATIONS Peer-Reviewed Journal Articles: “Truth is Never Out of Date”: The Political Thought of Robert Lewis Dabney,” Journal of Markets and Morality (In-Progress; Received Revise and Resubmit). “Calvin Coolidge: Classical Statesman,” Humanitas Journal, Vol. XXXII, Nos. 1 and 2 (2019). Book Reviews: “It’s a Perfect Time to Rediscover the Virtues of Andrew Jackson,” The Federalist (January 25, 2019). http://www.thefederalist.com/2019/01/25/rediscovering-the-virtues-of-andrew-jackson/ Online Journal Articles: “The Democratic Impulse of the Scholars in Friedrich Nietzsche’s Beyond Good and Evil,” Voegelin View (Forthcoming; Confirmed for Publication Nov. 2020). “Jean-Jacques Rousseau and Immanuel Kant’s Competing Views of the Enlightenment,” Voegelin View (Forthcoming; Confirmed for Publication Dec. -

Scientific Consensus in Policy and the Media

An Exercise in Scientific Integrity: Scientific Consensus in Policy and the Media I. The Importance of Scientific Consensus Science is a collaborative effort; over time, the ideas of many scientists are synthesized, modified, clarified, and sometimes discarded altogether as our understanding improves. Thus, science can be viewed as a method of reaching a consensus about the ways in which the world works. 1. From what you know about the scientific method, the peer review process, and the development of scientific theories, what does it mean when a scientific consensus emerges in a given field? 2. When science can have an impact on issues such as public health, environmental sustainability, and areas in which people have ethical or religious concerns (e.g., evolution, cloning), how should the existence of a scientific consensus affect the development of policy? 3. How should policy makers react to a scientific consensus that is politically or economically inconvenient? II. Skepticism Toward Scientific Consensus There are two unfortunate obstacles to an accurate public understanding of scientific consensus and its importance. First is a tendency to exaggerate the number of times scientific consensus has been overturned. This comes, in part, from the excitement of scientists, the public, and the media to new and untested ideas. When these attention- grabbing ideas prove mistaken or exaggerated during subsequent scientific review, this can give the impression that science has “failed.” There are certainly times when scientific consensus has been overturned, but such instances are rare. 4. How should policy makers react to cutting-edge science? Are there situations where policy decisions should be made before a scientific consensus has been reached, or should governments wait until the science is very clear? 5.