Bruce Springsteen Fan Behavior and Identification

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

048 LSA Springsteen2016. FINAL to SCOTT.Qxp:LSA Template

CONCERTS Copyright Lighting&Sound America March 2016 http://www.lightingandsoundamerica.com/LSA.html Ravitz notes that his design brief was that “there needed to be some vibe that harkened back to the way things felt in the 1980s.” 48 • March 2016 • Lighting&Sound America hen Bruce Springsteen and the E Street Band perform, the experience is akin to a marathon: The show can last up to four hours. Springsteen frequently changes up the W set list and takes requests from the audience, so every performance is unique. In December, Springsteen released The Ties that Bind: The River Collection, a four-CD-plus three-DVD special edition boxed set of The River—originally released in 1980— which included outtakes as well as photographs and other memorabilia. To celebrate the release, Springsteen and the band appeared on Saturday Take Me to Night Live; the rehearsals for the telecast led him to think about a tour. “The first call I got was that Bruce wanted to start tour rehearsals immediately after the SNL performance, since the band would be together and everyone would have had a warm-up,” explains Springsteen’s longtime production designer Jeff Ravitz, of Intensity Advisors, headquartered in North Hollywood, California. the River It was the holiday season, and the Bruce Springsteen revisits his time line that Springsteen was 1980 album with some very considering “nearly put me into an 2016 lighting technology apoplectic seizure,” Ravitz says. Thankfully, the artist reconsidered. By: Mary McGrath “Even considering Leonard Bernstein’s observation that great achievement can result from having ‘not quite enough time,’ Bruce admitted that it was probably a little too fast for the best planning,” Ravitz adds. -

PHILADELPHIA AREA E STREET BAND APPEARANCES (120+2) Within Nine-County (Pa./N.J./Del.) Area

[PDN: DN-PAGES-2--ADVANCE-3--SPORTS <FSN> ... 09/02/16] Author:VETRONB Date:09/02/16 Time:02:27 PHILADELPHIA AREA E STREET BAND APPEARANCES (120+2) Within Nine-County (Pa./N.J./Del.) Area GREETINGS FROM ASBURY PARK TOUR (26) 1976-77 TOUR (2) Saturday..................Oct. 28, 1972 ........................West Chester College ...................West Chester, Pa. Monday ...................Oct. 25, 1976 ........................Spectrum .......................................Philadelphia Wednesday .............Jan. 3, 1973 (Early)..............The Main Point ...............................Bryn Mawr, Pa. Wednesday .............Oct. 27, 1976 ........................Spectrum .......................................Philadelphia Wednesday .............Jan. 3, 1973 (Late) ..............The Main Point ...............................Bryn Mawr, Pa. Thursday .................Jan. 4, 1973 (Early)..............The Main Point ...............................Bryn Mawr, Pa. DARKNESS ON THE EDGE OF TOWN TOUR (4) Thursday .................Jan. 4, 1973 (Late) ..............The Main Point ...............................Bryn Mawr, Pa. Friday .......................May 26, 1978 .......................Spectrum .......................................Philadelphia Friday .......................Jan. 5, 1973 (Early)..............The Main Point ...............................Bryn Mawr, Pa. Saturday .................May 27, 1978 .......................Spectrum .......................................Philadelphia Friday .......................Jan. 5, 1973 (Late) ..............The -

Meanings and Measures Taken in Concert Observation of Bruce Springsteen, September 28, 1992, Los Angeles

UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations 1-1-1996 Meanings and measures taken in concert observation of Bruce Springsteen, September 28, 1992, Los Angeles Thomas J Rodak University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/rtds Repository Citation Rodak, Thomas J, "Meanings and measures taken in concert observation of Bruce Springsteen, September 28, 1992, Los Angeles" (1996). UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations. 3215. http://dx.doi.org/10.25669/bgs9-fpv1 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality' illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely afreet reproduction. -

The Backstreets Liner Notes

the backstreets liner notes BY ERIK FLANNIGAN AND CHRISTOPHER PHILLIPS eyond his insightful introductory note, Bruce Springsteen elected not to annotate the 66 songs 5. Bishop Danced RECORDING LOCATION: Max’s Kansas City, New included on Tracks. However, with the release York, NY of the box set, he did give an unprecedented RECORDING DATE: Listed as February 19, 1973, but Bnumber of interviews to publications like Billboard and MOJO there is some confusion about this date. Most assign the which revealed fascinating background details about these performance to August 30, 1972, the date given by the King songs, how he chose them, and why they were left off of Biscuit Flower Hour broadcast (see below), while a bootleg the albums in the first place. Over the last 19 years that this release of the complete Max’s set, including “Bishop Danced,” magazine has been published, the editors of Backstreets dated the show as March 7, 1973. Based on the known tour have attempted to catalog Springsteen’s recording and per- chronology and on comments Bruce made during the show, formance history from a fan’s perspective, albeit at times an the date of this performance is most likely January 31, 1973. obsessive one. This booklet takes a comprehensive look at HISTORY: One of two live cuts on Tracks, “Bishop Danced” all 66 songs on Tracks by presenting some of Springsteen’s was also aired on the inaugural King Biscuit Flower Hour and own comments about the material in context with each track’s reprised in the pre-show special to the 1988 Tunnel of Love researched history (correcting a few Tracks typos along the radio broadcast from Stockholm. -

Springsteen, a Three-Minute Song, a Life of Learning

Springsteen, A Three-Minute Song, A Life of Learning by Jin Thindal M.Ed., University of Sheffield, 1992 Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Curriculum Theory and Implementation Program Faculty of Education © Jin Thindal 2019 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Fall 2019 Copyright in this work rests with the author. Please ensure that any reproduction or re-use is done in accordance with the relevant national copyright legislation. Approval Name: Jin Thindal Degree: Doctor of Philosophy Title: Springsteen, A Three-Minute Song, A Life of Learning Examining Committee: Chair: Lynn Fels Professor Celeste Snowber Senior Supervisor Professor Allan MacKinnon Supervisor Associate Professor Michael Ling Internal Examiner Senior Lecturer Walter Gershon External Examiner Associate Professor School of Teaching, Learning & Curriculum Studies Kent State University Date Defended/Approved: December 9, 2019 ii Abstract This dissertation is an autobiographical and educational rendering of Bruce Springsteen’s influence on my life. Unbeknownst to him, Bruce Springsteen became my first proper ‘professor.’ Nowhere near the confines of a regular classroom, he opened the door to a kind of education like nothing I ever got in my formal schooling. From the very first notes of the song “Born in the U.S.A.,” he seized me and took me down a path of alternative learning. In only four minutes and forty seconds, the song revealed how little I knew of the world, despite all of my years in education, being a teacher, and holding senior positions. Like many people, I had thought that education was gained from the school system. -

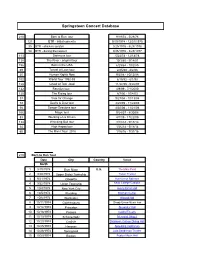

Springsteen Concert Database

Springsteen Concert Database 210 Born to Run tour 9/19/74 - 5/28/76 121 BTR - initial concerts 9/19/1974 - 12/31/1975 35 BTR - chicken scratch 3/25/1976 - 5/28/1976 54 BTR - during the lawsuit 9/26/1976 - 3/25/1977 113 Darkness tour 5/23/78 - 12/18/78 138 The River - original tour 10/3/80 - 9/14/81 156 Born in the USA 6/29/84 - 10/2/85 69 Tunnel of Love tour 2/25/88 - 8/2/88 20 Human Rights Now 9/2/88 - 10/15/88 102 World Tour 1992-93 6/15/92 - 6/1/93 128 Ghost of Tom Joad 11/22/95 - 5/26/97 132 Reunion tour 4/9/99 - 7/1/2000 120 The Rising tour 8/7/00 - 10/4/03 37 Vote for Change 9/27/04 - 10/13/04 72 Devils & Dust tour 4/25/05 - 11/22/05 56 Seeger Sessions tour 4/30/06 - 11/21/06 106 Magic tour 9/24/07 - 8/30/08 83 Working on a Dream 4/1/09 - 11/22/09 134 Wrecking Ball tour 3/18/12 - 9/18/13 34 High Hopes tour 1/26/14 - 5/18/14 65 The River Tour 2016 1/16/16 - 7/31/16 210 Born to Run Tour Date City Country Venue North America 1 9/19/1974 Bryn Mawr U.S. The Main Point 2 9/20/1974 Upper Darby Township Tower Theater 3 9/21/1974 Oneonta Hunt Union Ballroom 4 9/22/1974 Union Township Kean College Campus Grounds 5 10/4/1974 New York City Avery Fisher Hall 6 10/5/1974 Reading Bollman Center 7 10/6/1974 Worcester Atwood Hall 8 10/11/1974 Gaithersburg Shady Grove Music Fair 9 10/12/1974 Princeton Alexander Hall 10 10/18/1974 Passaic Capitol Theatre 11 10/19/1974 Schenectady Memorial Chapel 12 10/20/1974 Carlisle Dickinson College Dining Hall 13 10/25/1974 Hanover Spaulding Auditorium 14 10/26/1974 Springfield Julia Sanderson Theater 15 10/29/1974 Boston Boston Music Hall 16 11/1/1974 Upper Darby Tower Theater 17 11/2/1974 18 11/6/1974 Austin Armadillo World Headquarters 19 11/7/1974 20 11/8/1974 Corpus Christi Ritz Music Hall 21 11/9/1974 Houston Houston Music Hall 22 11/15/1974 Easton Kirby Field House 23 11/16/1974 Washington, D.C. -

Volume 4 • 2020 Published by Mcgill University

Volume 4 • 2020 Published by McGill University 2 Volume 4 • 2020 Managing Editor: Caroline Madden Editors: Jonathan D. Cohen Roxanne Harde Irwin Streight Editorial Board: Eric Alterman Jim Cullen Steven Fein Bryan Garman Stephen Hazan Arnoff Donna Luff Lorraine Mangione Lauren Onkey June Skinner Sawyers Bryant Simon Jerry Zolten Mission Statement BOSS: The Biannual Online-Journal of Springsteen Studies aims to publish scholarly, peer- reviewed essays pertaining to Bruce Springsteen. This open-access journal seeks to encourage consideration of Springsteen’s body of work primarily through the political, economic, and socio-cultural factors that have influenced his music and shaped its reception. BOSS welcomes broad interdisciplinary and cross-disciplinary approaches to Springsteen’s songwriting and performance. The journal aims to secure a place for Springsteen Studies in the contemporary academy. Submission Guidelines The editors of BOSS welcome submissions of articles that are rigorously researched and provide original, analytical approaches to Springsteen’s songwriting, performance, and fan community. Inter- and cross-disciplinary works, as well as studies that conform to specific disciplinary perspectives, are welcome. Suggested length of submission is between 15 and 25 pages. Contact To access BOSS, please visit http://boss.mcgill.ca/ Please address all queries and submissions to Caroline Madden (Managing Editor) at [email protected]. Cover Image By Danny Clinch. Used with kind permission from Shore Fire Media (http://shorefire.com/). Contents Introduction to BOSS Caroline Madden Contributors 7 Articles Everyday People: Elvis Presley, Bruce Springsteen, and the Gospel Tradition Brian Conniff 9 Signifying (and Psychoanalyzing) National Identity in Rock: Bruce Springsteen and The Tragically Hip Alexander Carpenter & Ian Skinner 50 Bruce Springsteen’s “Land of Hope and Dreams”: Towards Articulating and Assessing Its Inclusiveness Barry David 88 Reviews Long Walk Home: Reflections on Bruce Springsteen, edited by Jonathan D. -

SUGARLOAF MOUNTAIN an Appalachian Gathering

SUGARLOAF MOUNTAIN An Appalachian Gathering ON PERIOD INSTRUMENTS Prologue q THE MOUNTAINS OF RHÙM • Ross Hauck & Amanda Powell, vocals | arr. & adapted by J. Sorrell from the trad. Scottish, Cuillens of Rhùm [2:37] Crossing To The New World w FAREWELL TO IRELAND - HIGHLANDER’S FAREWELL • Susanna Perry Gilmore, trad. Irish & Appalachian reels, arr. J. Sorrell [3:42] e WE’LL RANT AND WE’LL ROAR (Farewell to the Isles) • Ross Hauck & Amanda Powell, vocals | trad. British & Canadian sea shanty, arr. J. Sorrell [3:17] Dark Mountain Home r THE CRUEL SISTER (Child Ballad #10) • Amanda Powell, vocals | trad. English/Appalachian ballad, arr. J. Sorrell [6:54] t SE FATH MO BUART HA (The Cause of All My Sorrow) - THE BUTTERFLY - BARNEY BRALLAGHAN • Kathie Stewart, trad. Irish, arr. K. Stewart [4:18] y NOTTAMUN TOWN (Roud #1044) • Brian Kay, medieval English & Appalachian ballad, arr. B. Kay [4:34] u BLACK IS THE COLOR OF MY TRUE LOVE’S HAIR (Roud #3103) • Ross Hauck, vocals | trad. Scots/Appalachian, arr. R. Schiffer & J. Sorrell [4:35] i I WONDER AS I WANDER - THE GRAVEL WALK - OVER THE ISLES TO AMERICA • Jeannette Sorrell, John Jacob Niles/trad. Appalachian/trad. Scottish, arr. J. Sorrell [4:19] Cornshuck Party o THE FOX WENT OUT ON A CHILLY NIGHT • Amanda Powell, vocals | trad. British/Appalachian ballad, arr. J. Sorrell [3:06] 1) OH SUSANNA! • Brian Kay & Ross Hauck, vocals; Susanna Perry Gilmore, minstrel song by Stephen Foster (1848), arr. J. Sorrell [5:02] PRETTY PEG - FAR FROM HOME • Susanna Perry Gilmore, / with René Schiffer, trad. Irish Reels, variations by R. -

December 25, 2015 Vol. 119 No. 52

VOL. 119 - NO. 52 BOSTON, MASSACHUSETTS, DECEMBER 25, 2015 $.35 A COPY A Very Merry Christmas to our Readers and Advertisers from the staff of the Post-Gazette Pam Donnaruma Christian A. Claude Marsilia Guarino Jeanne Brady Freeway Mrs. Joanne Murphy Fraser Joan Smith Frances Jeanette Fitzgerald Cataldo Bobby Franklin DECEMBER 31, 2015 - JANUARY 1, 2016 Mary DiZazzo HIGHLIGH TS Bob ditions: Star of the Day, and has Morello opened for acts such as Jason Lancaster (of Mayday Parade), Ed CampochiaroLouie Shallow GraffeoDom Hawthorne Heights and Alex Preston. BarronRay AURORA BOREALIS David DANCE COMPANY Rosario Trumbull Aurora Borealis is thrilled to Scabin Samantha Josephine Ally dance their way into the new John Christoforo Bennett Di Censo Molinari year at Copley Square and in- Chu Ling Symynkywicz spire the entire community with Sal Giarratani Lisa Orazio their passionate and artistic perience in wind performance. Cappuccio Buttafuoco Richard Girard Plante performance. Specializing in Members have performed with Molinari Daniel contemporary and improvi- the Boston Pops and Boston Richard Preiss Di Censo sational dance forms, ABDC Symphony Orchestra. Angela provides ample opportunities BRADLEY Cornacchio Alessandra Sambiase Alex Preston for growth, performance, and BARTLETT-ROACHE inspiring experiences. Thirteen-year-old solo pia- ALEX PRESTON BOSTON SAXOPHONE nist, tenor saxophonist, vocal- Twenty-two-year-old singer- QUARTET ist, and composer from Mas- songwriter Alex Preston was A unique blend of musicians sachusetts, Bradley was voted News Briefs second runner-up on the 13th combining a tremendous range Boston’s Top Instrumentalist of repertoire and individual ex- by Sal Giarratani season of American Idol in by the Young Performer’s Club 2014. -

A Political Companion to John Steinbeck

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Literature in English, North America English Language and Literature 5-29-2013 A Political Companion to John Steinbeck Cyrus Ernesto Zirakzadeh University of Connecticut Simon Stow The College of William and Mary Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Thanks to the University of Kentucky Libraries and the University Press of Kentucky, this book is freely available to current faculty, students, and staff at the University of Kentucky. Find other University of Kentucky Books at uknowledge.uky.edu/upk. For more information, please contact UKnowledge at [email protected]. Recommended Citation Zirakzadeh, Cyrus Ernesto and Stow, Simon, "A Political Companion to John Steinbeck" (2013). Literature in English, North America. 76. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/upk_english_language_and_literature_north_america/76 continued from front flap political science / literature Zirakzadeh a political companion to and Stow John Steinbeck John Steinbeck Prior investigations of Steinbeck’s political “This volume offers finely crafted essays that explore the a political companion to Edited by Cyrus Ernesto Zirakzadeh thought have been either episodic, looking at relationship between the political and the literary in diverse ways. and Simon Stow a particular problem or a single work, or have These compelling essays assess the motivations and ambiguities in approached their subject within a broader Steinbeck’s engagement with politics and nationhood and trace how Though he was a recipient of both the biographical format, relating the writer’s ideas that engagement is transfigured as literary art. Essays about Steinbeck Pulitzer Prize and the Nobel Prize for almost entirely to his personal experiences. -

Bruce Springsteen and the E Street Band 1975 Free

FREE BRUCE SPRINGSTEEN AND THE E STREET BAND 1975 PDF Barbara Pyle | 224 pages | 23 Nov 2015 | Reel Art Press | 9781909526341 | English | London, United Kingdom Subscribe to read | Financial Times More Images. Please enable Javascript to take full advantage of our site features. Edit Master Release. It consists of 40 tracks recorded at various concerts between and The album was released as a box set by Columbia Records on November 10, Box set release formats include five vinyl records, three cassettes, or three CDs. There was also a record club only release which came on three 8-track cartridges. Garry Tallent Backing Vocals, Bass. Toby Scott Engineer, Recorded By. Jon Landau Management, Producer. Sandra Choron Art Direction. Patti Scialfa Backing Vocals. Biff Dawes Crew. Mays 4 Crew. McConnel Crew. Pete Carlson 2 Crew. Sandelson Crew. Bill Freesh Crew. Bob Winder Crew. David Bianco Crew. Jack Crymes Crew. Jim Scott Crew. Mark Eshelman Bruce Springsteen and the E Street Band 1975. Mike Novitch Crew. Nick Basich Crew. Scott Stogel Crew. Fritz Lang Crew. Matteotti Crew. Kooster McAllister Crew. Phil Gitomer Crew. Max Weinberg Drums. Barbara Carr 2 Management. Denise Sileci Management. Bob Ludwig Mastered By. Bob Clearmountain Mixed By. Paul Hamingson Mixed By. Aaron Rapoport Photography By. Annie Leibovitz Photography By. David Gahr Photography By. Eric Meola Photography By. Frank Stefanko Photography By. Jacquelyn Walsh Photography By. Jim Marchese Photography By. Jimmy Wachtel Photography By. Joel Bernstein Photography By. Peter Cunningham 2 Photography By. Watt Casey Photography By. Neal Preston Photography By. Chuck Plotkin Producer. Jimmy Iovine Recorded By. Craig Vogel Technician. -

“THE DISTANCE BETWEEN AMERICAN REALITY and the AMERICAN DREAM”: BRUCE SPRINGSTEEN's AMERICAN JEREMIAD, 2002-2012 by Robert

“THE DISTANCE BETWEEN AMERICAN REALITY AND THE AMERICAN DREAM”: BRUCE SPRINGSTEEN’S AMERICAN JEREMIAD, 2002-2012 by Robert Scott McMillan A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English Middle Tennessee State University December 2016 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Pete McCluskey, Chair Dr. Mischa Renfroe Dr. Patricia Bradley This dissertation is dedicated with all the love in my heart to my wife and eternal partner, Jennifer James, who is my dream, my miracle, my absolute joy, and the love of my life. This dissertation is also dedicated in memory of my parents, Bob and Martha McMillan who both instilled in me a true love of learning and the desire to pursue my dreams. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank the members of my dissertation committee, Dr. Pete McCluskey, Dr. Mischa Renfroe, and Dr. Patricia Bradley for their patience and support of this project and for their many comments and helpful suggestions. I would also like to thank Dr. Kevin Donovan, the late Dr. David Lavery, and Dr. Rhonda McDaniel for their support. I would also like to thank my family at Volunteer State Community College for their encouragement and support of this dissertation, especially my friends and colleagues Laura Black, Dr. Carole Bucy, Dr. Joe Douglas, Dr. Mickey Hall, Dr. Merritt McKinney, and Dr. Shellie Michael, as well as Dean Phyllis Foley and Vice-President for Academic Affairs Dr. George Pimentel for the institutional support in support of this project. Finally, a special thank you to Bruce Springsteen. Elizabeth Wurtzel has described Springsteen as “a force of good, a presence of thoughtfulness” (73), and I believe these qualities come out in every song, album, performance, and speech.