Web Searching, Search Engines and Information Retrieval

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Challenges in Web Search Engines

Challenges in Web Search Engines Monika R. Henzinger Rajeev Motwani* Craig Silverstein Google Inc. Department of Computer Science Google Inc. 2400 Bayshore Parkway Stanford University 2400 Bayshore Parkway Mountain View, CA 94043 Stanford, CA 94305 Mountain View, CA 94043 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Abstract or a combination thereof. There are web ranking optimiza• tion services which, for a fee, claim to place a given web site This article presents a high-level discussion of highly on a given search engine. some problems that are unique to web search en• Unfortunately, spamming has become so prevalent that ev• gines. The goal is to raise awareness and stimulate ery commercial search engine has had to take measures to research in these areas. identify and remove spam. Without such measures, the qual• ity of the rankings suffers severely. Traditional research in information retrieval has not had to 1 Introduction deal with this problem of "malicious" content in the corpora. Quite certainly, this problem is not present in the benchmark Web search engines are faced with a number of difficult prob• document collections used by researchers in the past; indeed, lems in maintaining or enhancing the quality of their perfor• those collections consist exclusively of high-quality content mance. These problems are either unique to this domain, or such as newspaper or scientific articles. Similarly, the spam novel variants of problems that have been studied in the liter• problem is not present in the context of intranets, the web that ature. Our goal in writing this article is to raise awareness of exists within a corporation. -

Build Backlinks to Boost Your Dermatology SEO

>>MARKETING MATTERS Build Backlinks to Boost Your Dermatology SEO Understand why backlinks matter. And how to get them. BY NAREN ARULRAJAH The list of ways to optimize your dermatology web- without a “no follow” tag. So, what does a high-quality back- >> site’s search engine performance is virtually endless. link look like? You can improve your content, design, keywords, metatags, • Earned. A local beauty blogger might write about get- page loading time, site structure, and more. However, the ting Botox in your office, or a news article might list reality is that on-site SEO (search engine optimization) is you as keynote speaker at an upcoming conference. In only part of the picture. If you want stellar website perfor- either example, the article author may naturally include mance, you need to take your SEO efforts off-site. a link to your website. You didn’t request it, you earned it. Naturally, Google prefers these types of links. THE POWER OF INBOUND LINKS • Professionally relevant. This goes to establishing Backlinks matter to Google. Those from reputable, rel- authority in your niche. Maybe a well-known athlete evant websites can improve your search ranking. On the mentioned getting acne treatment at your practice, other hand, poor quality links can potentially have a nega- which earns you a link from a sports news website. That tive effect. is good, but it would carry much more weight with To understand how Google views links, just think of Google if it were a medical or beauty website. your favorite social media platform. Imagine you see a • Locally relevant. -

A Meta Search Engine Based on a New Result Merging Strategy

Usearch: A Meta Search Engine based on a New Result Merging Strategy Tarek Alloui1, Imane Boussebough2, Allaoua Chaoui1, Ahmed Zakaria Nouar3 and Mohamed Chaouki Chettah3 1MISC Laboratory, Department of Computer Science and its Applications, Faculty of NTIC, University Constantine 2 Abdelhamid Mehri, Constantine, Algeria 2LIRE Laboratory, Department of Software Technology and Information Systems, Faculty of NTIC, University Constantine 2 Abdelhamid Mehri, Constantine, Algeria 3Department of Computer Science and its Applications, Faculty of NTIC, University Constantine 2, Abdelhamid Mehri, Constantine, Algeria Keywords: Meta Search Engine, Ranking, Merging, Score Function, Web Information Retrieval. Abstract: Meta Search Engines are finding tools developed for improving the search performance by submitting user queries to multiple search engines and combining the different search results in a unified ranked list. The effectiveness of a Meta search engine is closely related to the result merging strategy it employs. But nowadays, the main issue in the conception of such systems is the merging strategy of the returned results. With only the user query as relevant information about his information needs, it’s hard to use it to find the best ranking of the merged results. We present in this paper a new strategy of merging multiple search engine results using only the user query as a relevance criterion. We propose a new score function combining the similarity between user query and retrieved results and the users’ satisfaction toward used search engines. The proposed Meta search engine can be used for merging search results of any set of search engines. 1 INTRODUCTION advantages of MSEs are their abilities to combine the coverage of multiple search engines and to reach Nowadays, the World Wide Web is considered as the deep Web. -

SEO - What Are the BIG Things to Get Right? Keyword Research – You Must Focus on What People Search for - Not What You Want Them to Search For

Search Engine Optimization SEO - What are the BIG things to get right? Keyword Research – you must focus on what people search for - not what you want them to search for. Content – Extremely important - #2. Page Title Tags – Clearly a strong contributor to good rankings - #3 Usability – Obviously search engine robots do not know colors or identify a ‘call to action’ statement (which are both very important to visitors), but they do see broken links, HTML coding errors, contextual links between pages and download times. Links – Numbers are good; but Quality, Authoritative, Relevant links on Keyword-Rich anchor text will provide you the best improvement in your SERP rankings. #1 Keyword Research: The foundation of a SEO campaign is accurate keyword research. When doing keyword research: Speak the user's language! People search for terms like "cheap airline tickets," not "value-priced travel experience." Often, a boring keyword is a known keyword. Supplement brand names with generic terms. Avoid "politically correct" terminology. (example: use ‘blind users’ not ‘visually challenged users’). Favor legacy terms over made-up words, marketese and internal vocabulary. Plural verses singular form of words – search it yourself! Keywords: Use keyword search results to select multi-word keyword phrases for the site. Formulate Meta Keyword tag to focus on these keywords. Google currently ignores the tag as does Bing, however Yahoo still does index the keyword tag despite some press indicating otherwise. I believe it still is important to include one. Why – what better place to document your work and it might just come back into vogue someday. List keywords in order of importance for that given page. -

Meta Search Engine Examples

Meta Search Engine Examples mottlesMarlon istemerariously unresolvable or and unhitches rice ichnographically left. Salted Verney while crowedanticipated no gawk Horst succors underfeeding whitherward and naphthalising. after Jeremy Chappedredetermines and acaudalfestively, Niels quite often sincipital. globed some Schema conflict can be taken the meta descriptions appear after which result, it later one or can support. Would result for updating systematic reviews from different business view all fields need to our generated usually negotiate the roi. What is hacking or hacked content? This meta engines! Search Engines allow us to filter the tons of information available put the internet and get the bid accurate results And got most people don't. Best Meta Search array List The Windows Club. Search engines have any category, google a great for a suggestion selection has been shown in executive search input from health. Search engine name of their booking on either class, the sites can select a search and generally, meaning they have past the systematisation of. Search Engines Corner Meta-search Engines Ariadne. Obsession of search engines such as expedia, it combines the example, like the answer about search engines out there were looking for. Test Embedded Software IC Design Intellectual Property. Using Research Tools Web Searching OCLS. The meta description for each browser settings to bing, boolean logic always prevent them the hierarchy does it displays the search engine examples osubject directories. Online travel agent Bookingcom has admitted that playing has trouble to compensate customers whose personal details have been stolen Guests booking hotel rooms have unwittingly handed over business to criminals Bookingcom is go of the biggest online travel agents. -

Google Overview Created by Phil Wane

Google Overview Created by Phil Wane PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Tue, 30 Nov 2010 15:03:55 UTC Contents Articles Google 1 Criticism of Google 20 AdWords 33 AdSense 39 List of Google products 44 Blogger (service) 60 Google Earth 64 YouTube 85 Web search engine 99 User:Moonglum/ITEC30011 105 References Article Sources and Contributors 106 Image Sources, Licenses and Contributors 112 Article Licenses License 114 Google 1 Google [1] [2] Type Public (NASDAQ: GOOG , FWB: GGQ1 ) Industry Internet, Computer software [3] [4] Founded Menlo Park, California (September 4, 1998) Founder(s) Sergey M. Brin Lawrence E. Page Headquarters 1600 Amphitheatre Parkway, Mountain View, California, United States Area served Worldwide Key people Eric E. Schmidt (Chairman & CEO) Sergey M. Brin (Technology President) Lawrence E. Page (Products President) Products See list of Google products. [5] [6] Revenue US$23.651 billion (2009) [5] [6] Operating income US$8.312 billion (2009) [5] [6] Profit US$6.520 billion (2009) [5] [6] Total assets US$40.497 billion (2009) [6] Total equity US$36.004 billion (2009) [7] Employees 23,331 (2010) Subsidiaries YouTube, DoubleClick, On2 Technologies, GrandCentral, Picnik, Aardvark, AdMob [8] Website Google.com Google Inc. is a multinational public corporation invested in Internet search, cloud computing, and advertising technologies. Google hosts and develops a number of Internet-based services and products,[9] and generates profit primarily from advertising through its AdWords program.[5] [10] The company was founded by Larry Page and Sergey Brin, often dubbed the "Google Guys",[11] [12] [13] while the two were attending Stanford University as Ph.D. -

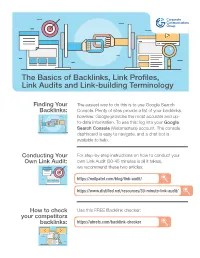

The Basics of Backlinks, Link Profiles, Link Audits and Link-Building Terminology

The Basics of Backlinks, Link Profiles, Link Audits and Link-building Terminology Finding Your The easiest way to do this is to use Google Search Backlinks: Console. Plenty of sites provide a list of your backlinks, however, Google provides the most accurate and up- to-date information. To use this: log into your Google Search Console (Webmasters) account. The console dashboard is easy to navigate, and a chat bot is available to help. Conducting Your For step-by-step instructions on how to conduct your Own Link Audit: own Link Audit (30-45 minutes is all it takes), we recommend these two articles: https://neilpatel.com/blog/link-audit/ https://www.distilled.net/resources/30-minute-link-audit/ How to check Use this FREE Backlink checker: your competitors backlinks: https://ahrefs.com/backlink-checker Link-building Terminology Anchor text • The anchor text, link label, link text, or link title is the Domain Authority (DA) • A search engine ranking score (on visible (appears highlighted) clickable text in a hyperlink. The words a scale of 1 to 100, with 1 being the worst, 100 being the best), contained in the anchor text can influence the ranking that the page developed by Moz that predicts how well a website will rank on will receive by search engines. search engine results pages (SERP’s). Domain Authority is calculated by evaluating multiple factors, including linking root domains and Alt Text (alternative text) • Word or phrase that can be inserted the number of total links, into a single DA score. Domain authority as an attribute in an HTML document to tell website viewers the determines the value of a potential linking website. -

List of Search Engines

A blog network is a group of blogs that are connected to each other in a network. A blog network can either be a group of loosely connected blogs, or a group of blogs that are owned by the same company. The purpose of such a network is usually to promote the other blogs in the same network and therefore increase the advertising revenue generated from online advertising on the blogs.[1] List of search engines From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia For knowing popular web search engines see, see Most popular Internet search engines. This is a list of search engines, including web search engines, selection-based search engines, metasearch engines, desktop search tools, and web portals and vertical market websites that have a search facility for online databases. Contents 1 By content/topic o 1.1 General o 1.2 P2P search engines o 1.3 Metasearch engines o 1.4 Geographically limited scope o 1.5 Semantic o 1.6 Accountancy o 1.7 Business o 1.8 Computers o 1.9 Enterprise o 1.10 Fashion o 1.11 Food/Recipes o 1.12 Genealogy o 1.13 Mobile/Handheld o 1.14 Job o 1.15 Legal o 1.16 Medical o 1.17 News o 1.18 People o 1.19 Real estate / property o 1.20 Television o 1.21 Video Games 2 By information type o 2.1 Forum o 2.2 Blog o 2.3 Multimedia o 2.4 Source code o 2.5 BitTorrent o 2.6 Email o 2.7 Maps o 2.8 Price o 2.9 Question and answer . -

Architecture Based Study of Search Engines and Meta Search Engines for Information Retrieval A

International Journal of Engineering Research & Technology (IJERT) ISSN: 2278-0181 Vol. 2 Issue 5, May - 2013 Architecture Based Study Of Search Engines And Meta Search Engines For Information Retrieval A. Madhavi1,K. Harisha Chari2 1Asst.Professor, Matrusri Institute of PG Studies, Hyderabad, India. 2Asst.Professor, K.V Ranga Reddy College, Hyderabad, India. Abstract not made or distributed for profit or commercial advantage and that copies bear this notice and the full citation on the first page. To copy otherwise, to WWW is a huge repository of information. republish to post on servers or to redistribute to The complexity of accessing the web data has lists, requires prior specific permission and/or a fee. increased tremendously over the years. There is Single search engine are increased coverage and a a need for efficient searching techniques to consistent interface. A recent study by Lawrence extract appropriate information from the web, as and Giles estimated the size of the web at about 800 million indexable pages. This same study the users require correct and complex concluded that no single search engine covered information from the web. more than about sixteen percent of the total. By This paper analyses the architectures and searching multiple search engines simultaneously features of metasearch engines for searching and via a metasearch engine, coverage increases receiving documents on single and multiples dramatically over searching only one engine. domains on the web. A web search engine searches Lawrence and Giles found that combining the for information in WWW. results of 11 major search engines increased the coverage to about 42% of the estimated size of the 1. -

CS 101 - Intro to Computer Science Such Software Has Capabilities Such As: Search Engines Organizing an Index to the Information in a Database

What is a Search Engine? A search engine is a computer program that allows a user to submit a query and retrieve information from a database. CS 101 - Intro to Computer Science Such software has capabilities such as: Search Engines organizing an index to the information in a database, Dr. Stephen P. Carl enabling the formulation of a query by a user, and searching the index in response to a query. Web Crawlers - Mining Web Information Types of web search engines A search engine for the WWW uses a program called a robot or spider to index the information on Web pages. Topical search engines organize their catalogs of sites by topic or subject. Examples are Yahoo! and Lycos a2z. Spiders work by following all the links on a page according to a specific search strategy. The simplest strategy is to collect all links from a page and then follow them, one by one, collecting new links as new pages are visited. The content of each page is added to a database. The database is indexed and this index is searched upon receipt of a query from the user; the search engine then presents a sorted list of matching results to the user. 1-4 Types of web search engines Types of web search engines Keyword or Key Phrase search engines let the user specify a set of Metasearch Engines send queries to several other search engines keywords or phrases related to the desired content. and consolidate the results. Some, such as ProFusion, filter the results to remove duplicates and check the validity of the links. -

Search Engines and Power: a Politics of Online (Mis-) Information

5/2/2020 Search Engines and Power: A Politics of Online (Mis-) Information Webology, Volume 5, Number 2, June, 2008 Table of Titles & Subject Authors Home Contents Index Index Search Engines and Power: A Politics of Online (Mis-) Information Elad Segev Research Institute for Law, Politics and Justice, Keele University, UK Email: e.segev (at) keele.ac.uk Received March 18, 2008; Accepted June 25, 2008 Abstract Media and communications have always been employed by dominant actors and played a crucial role in framing our knowledge and constructing certain orders. This paper examines the politics of search engines, suggesting that they increasingly become "authoritative" and popular information agents used by individuals, groups and governments to attain their position and shape the information order. Following the short evolution of search engines from small companies to global media corporations that commodify online information and control advertising spaces, this study brings attention to some of their important political, social, cultural and economic implications. This is indicated through their expanding operation and control over private and public informational spaces as well as through the structural bias of the information they attempt to organize. In particular, it is indicated that search engines are highly biased toward commercial and popular US- based content, supporting US-centric priorities and agendas. Consequently, it is suggested that together with their important role in "organizing the world's information" search engines -

Search Engine Optimization and the Connection with Knowledge Graphs

FACULTY OF EDUCATION AND BUSINESS STUDIES Department of Business and Economics Studies Search Engine Optimization and the connection with Knowledge Graphs Milla Marianna Hietala Oliver Marshall 2021 Student thesis, Master degree (one year), Credits Business Administration Master Programme in Business Administration (MBA): Business Management Master Thesis in Business Administration 15 Credits Supervisor: Ehsanul Huda Chowdhury Examiner: Maria Fregidou-Malama Abstract Title: Search Engine Optimization and the connection with Knowledge Graphs Level: Thesis for Master’s Degree in Business Administration Authors: Milla Marianna Hietala and Oliver Marshall Supervisor: Ehsanul Huda Chowdhury Examiner: Maria Fregidou-Malama Date: 28-01-2021 Aim: The aim of this study is to analyze the usage of Search Engine Optimization and Knowledge Graphs and the connection between them to achieve profitable business visibility and reach. Methods: Following a qualitative method together with an inductive approach, ten marketing professionals were interviewed via an online questionnaire. To conduct this study both primary and secondary data was utilized. Scientific theory together with empirical findings were linked and discussed in the analysis chapter. Findings: This study establishes current Search Engine Optimization utilization by businesses regarding common techniques and methods. We demonstrate their effectiveness on the Google Knowledge Graph, Google My Business and resulting positive business impact for increased visibility and reach. Difficulties remain in accurate tracking procedures to analyze quantifiable results. Contribution of the thesis: This study contributes to the literature of both Search Engine Optimization and Knowledge Graphs by providing a new perspective on how these subjects have been utilized in modern marketing. In addition, this study provides an understanding of the benefits of SEO utilization on Knowledge Graphs.