Search Engines and Power: a Politics of Online (Mis-) Information

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Challenges in Web Search Engines

Challenges in Web Search Engines Monika R. Henzinger Rajeev Motwani* Craig Silverstein Google Inc. Department of Computer Science Google Inc. 2400 Bayshore Parkway Stanford University 2400 Bayshore Parkway Mountain View, CA 94043 Stanford, CA 94305 Mountain View, CA 94043 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Abstract or a combination thereof. There are web ranking optimiza• tion services which, for a fee, claim to place a given web site This article presents a high-level discussion of highly on a given search engine. some problems that are unique to web search en• Unfortunately, spamming has become so prevalent that ev• gines. The goal is to raise awareness and stimulate ery commercial search engine has had to take measures to research in these areas. identify and remove spam. Without such measures, the qual• ity of the rankings suffers severely. Traditional research in information retrieval has not had to 1 Introduction deal with this problem of "malicious" content in the corpora. Quite certainly, this problem is not present in the benchmark Web search engines are faced with a number of difficult prob• document collections used by researchers in the past; indeed, lems in maintaining or enhancing the quality of their perfor• those collections consist exclusively of high-quality content mance. These problems are either unique to this domain, or such as newspaper or scientific articles. Similarly, the spam novel variants of problems that have been studied in the liter• problem is not present in the context of intranets, the web that ature. Our goal in writing this article is to raise awareness of exists within a corporation. -

Building a Scalable Index and a Web Search Engine for Music on the Internet Using Open Source Software

Department of Information Science and Technology Building a Scalable Index and a Web Search Engine for Music on the Internet using Open Source software André Parreira Ricardo Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master in Computer Science and Business Management Advisor: Professor Carlos Serrão, Assistant Professor, ISCTE-IUL September, 2010 Acknowledgments I should say that I feel grateful for doing a thesis linked to music, an art which I love and esteem so much. Therefore, I would like to take a moment to thank all the persons who made my accomplishment possible and hence this is also part of their deed too. To my family, first for having instigated in me the curiosity to read, to know, to think and go further. And secondly for allowing me to continue my studies, providing the environment and the financial means to make it possible. To my classmate André Guerreiro, I would like to thank the invaluable brainstorming, the patience and the help through our college years. To my friend Isabel Silva, who gave me a precious help in the final revision of this document. Everyone in ADETTI-IUL for the time and the attention they gave me. Especially the people over Caixa Mágica, because I truly value the expertise transmitted, which was useful to my thesis and I am sure will also help me during my professional course. To my teacher and MSc. advisor, Professor Carlos Serrão, for embracing my will to master in this area and for being always available to help me when I needed some advice. -

La Sécurité Informatique Edition Livres Pour Tous (

La sécurité informatique Edition Livres pour tous (www.livrespourtous.com) PDF générés en utilisant l’atelier en source ouvert « mwlib ». Voir http://code.pediapress.com/ pour plus d’informations. PDF generated at: Sat, 13 Jul 2013 18:26:11 UTC Contenus Articles 1-Principes généraux 1 Sécurité de l'information 1 Sécurité des systèmes d'information 2 Insécurité du système d'information 12 Politique de sécurité du système d'information 17 Vulnérabilité (informatique) 21 Identité numérique (Internet) 24 2-Attaque, fraude, analyse et cryptanalyse 31 2.1-Application 32 Exploit (informatique) 32 Dépassement de tampon 34 Rétroingénierie 40 Shellcode 44 2.2-Réseau 47 Attaque de l'homme du milieu 47 Attaque de Mitnick 50 Attaque par rebond 54 Balayage de port 55 Attaque par déni de service 57 Empoisonnement du cache DNS 66 Pharming 69 Prise d'empreinte de la pile TCP/IP 70 Usurpation d'adresse IP 71 Wardriving 73 2.3-Système 74 Écran bleu de la mort 74 Fork bomb 82 2.4-Mot de passe 85 Attaque par dictionnaire 85 Attaque par force brute 87 2.5-Site web 90 Cross-site scripting 90 Défacement 93 2.6-Spam/Fishing 95 Bombardement Google 95 Fraude 4-1-9 99 Hameçonnage 102 2.7-Cloud Computing 106 Sécurité du cloud 106 3-Logiciel malveillant 114 Logiciel malveillant 114 Virus informatique 120 Ver informatique 125 Cheval de Troie (informatique) 129 Hacktool 131 Logiciel espion 132 Rootkit 134 Porte dérobée 145 Composeur (logiciel) 149 Charge utile 150 Fichier de test Eicar 151 Virus de boot 152 4-Concepts et mécanismes de sécurité 153 Authentification forte -

A Study on Vertical and Broad-Based Search Engines

International Journal of Latest Trends in Engineering and Technology IJLTET Special Issue- ICRACSC-2016 , pp.087-093 e-ISSN: 2278-621X A STUDY ON VERTICAL AND BROAD-BASED SEARCH ENGINES M.Swathi1 and M.Swetha2 Abstract-Vertical search engines or Domain-specific search engines[1][2] are becoming increasingly popular because they offer increased accuracy and extra features not possible with general, Broad-based search engines or Web-wide search engines. The paper focuses on the survey of domain specific search engine which is becoming more popular as compared to Web- Wide Search Engines as they are difficult to maintain and time consuming .It is also difficult to provide appropriate documents to represent the target data. We also listed various vertical search engines and Broad-based search engines. Index terms: Domain specific search, vertical search engines, broad based search engines. I. INTRODUCTION The Web has become a very rich source of information for almost any field, ranging from music to histories, from sports to movies, from science to culture, and many more. However, it has become increasingly difficult to search for desired information on the Web. Users are facing the problem of information overload , in which a search on a general-purpose search engine such as Google (www.google.com) results in thousands of hits.Because a user cannot specify a search domain (e.g. medicine, music), a search query may bring up Web pages both within and outside the desired domain. Example 1: A user searching for “cancer” may get Web pages related to the disease as well as those related to the Zodiac sign. -

Towards Active SEO 2

JISTEM - Journal of Information Systems and Technology Management Revista de Gestão da Tecnologia e Sistemas de Informação Vol. 9, No. 3, Sept/Dec., 2012, pp. 443-458 ISSN online: 1807-1775 DOI: 10.4301/S1807-17752012000300001 TOWARDS ACTIVE SEO (SEARCH ENGINE OPTIMIZATION) 2.0 Charles-Victor Boutet (im memoriam) Luc Quoniam William Samuel Ravatua Smith South University Toulon-Var - Ingémédia, France ____________________________________________________________________________ ABSTRACT In the age of writable web, new skills and new practices are appearing. In an environment that allows everyone to communicate information globally, internet referencing (or SEO) is a strategic discipline that aims to generate visibility, internet traffic and a maximum exploitation of sites publications. Often misperceived as a fraud, SEO has evolved to be a facilitating tool for anyone who wishes to reference their website with search engines. In this article we show that it is possible to achieve the first rank in search results of keywords that are very competitive. We show methods that are quick, sustainable and legal; while applying the principles of active SEO 2.0. This article also clarifies some working functions of search engines, some advanced referencing techniques (that are completely ethical and legal) and we lay the foundations for an in depth reflection on the qualities and advantages of these techniques. Keywords: Active SEO, Search Engine Optimization, SEO 2.0, search engines 1. INTRODUCTION With the Web 2.0 era and writable internet, opportunities related to internet referencing have increased; everyone can easily create their virtual territory consisting of one to thousands of sites, and practically all 2.0 territories are designed to be participatory so anyone can write and promote their sites. -

Build Backlinks to Boost Your Dermatology SEO

>>MARKETING MATTERS Build Backlinks to Boost Your Dermatology SEO Understand why backlinks matter. And how to get them. BY NAREN ARULRAJAH The list of ways to optimize your dermatology web- without a “no follow” tag. So, what does a high-quality back- >> site’s search engine performance is virtually endless. link look like? You can improve your content, design, keywords, metatags, • Earned. A local beauty blogger might write about get- page loading time, site structure, and more. However, the ting Botox in your office, or a news article might list reality is that on-site SEO (search engine optimization) is you as keynote speaker at an upcoming conference. In only part of the picture. If you want stellar website perfor- either example, the article author may naturally include mance, you need to take your SEO efforts off-site. a link to your website. You didn’t request it, you earned it. Naturally, Google prefers these types of links. THE POWER OF INBOUND LINKS • Professionally relevant. This goes to establishing Backlinks matter to Google. Those from reputable, rel- authority in your niche. Maybe a well-known athlete evant websites can improve your search ranking. On the mentioned getting acne treatment at your practice, other hand, poor quality links can potentially have a nega- which earns you a link from a sports news website. That tive effect. is good, but it would carry much more weight with To understand how Google views links, just think of Google if it were a medical or beauty website. your favorite social media platform. Imagine you see a • Locally relevant. -

Lecture 18: CS 5306 / INFO 5306: Crowdsourcing and Human Computation Web Link Analysis (Wisdom of the Crowds) (Not Discussing)

Lecture 18: CS 5306 / INFO 5306: Crowdsourcing and Human Computation Web Link Analysis (Wisdom of the Crowds) (Not Discussing) • Information retrieval (term weighting, vector space representation, inverted indexing, etc.) • Efficient web crawling • Efficient real-time retrieval Web Search: Prehistory • Crawl the Web, generate an index of all pages – Which pages? – What content of each page? – (Not discussing this) • Rank documents: – Based on the text content of a page • How many times does query appear? • How high up in page? – Based on display characteristics of the query • For example, is it in a heading, italicized, etc. Link Analysis: Prehistory • L. Katz. "A new status index derived from sociometric analysis“, Psychometrika 18(1), 39-43, March 1953. • Charles H. Hubbell. "An Input-Output Approach to Clique Identification“, Sociolmetry, 28, 377-399, 1965. • Eugene Garfield. Citation analysis as a tool in journal evaluation. Science 178, 1972. • G. Pinski and Francis Narin. "Citation influence for journal aggregates of scientific publications: Theory, with application to the literature of physics“, Information Processing and Management. 12, 1976. • Mark, D. M., "Network models in geomorphology," Modeling in Geomorphologic Systems, 1988 • T. Bray, “Measuring the Web”. Proceedings of the 5th Intl. WWW Conference, 1996. • Massimo Marchiori, “The quest for correct information on the Web: hyper search engines”, Computer Networks and ISDN Systems, 29: 8-13, September 1997, Pages 1225-1235. Hubs and Authorities • J. Kleinberg. “Authoritative -

Wikia Search: La Transparencia Es Un Arma Cargada De Futuro Por Fabrizio Ferraro

Wikia search: la transparencia es un arma Cargada de futuro Por Fabrizio Ferraro Lo que hace de Wikia Search un proyecto potencialmente innovador no es ni la intervención del Claves factor humano ni la calidad de los resultados de las búsquedas. Su posible ventaja competitiva es la transparencia, que podría convertirlo en el buscador más 1 Wikia Search se basa en el concepto del wiki, un término fiable en cuanto a la neutralidad de sus resultados. que designa a las sedes web que se nutren de los Sin embargo, Wikia Search no ha empezado con buen pie. contenidos que aportan los propios usuarios. El ejemplo “Una de las mayores decepciones que he tenido la de wiki más célebre es desgracia de tener que comentar”, se afirma en la crítica Wikipedia, que Nielsen situaba en noveno lugar en el del influyente blog de tecnología TechCrunch. La mayoría ranking de sedes más de artículos de la prensa y de los blogs reflejan visitadas por los internautas sentimientos parecidos. Es una reacción chocante por estadounidenses a finales de 2007. cuanto han sido estos mismos medios los que han creado más expectativas sobre el nuevo motor de búsqueda “social” llamado a disputarle el trono a Google. El buscador de Wikia 2 Search utiliza tecnología de Las críticas se han ensañado especialmente con los código abierto que, paupérrimos resultados que arroja el nuevo motor de contrariamente a la que utilizan sus rivales, permite a búsqueda en comparación con los que ofrece Google. los propios usuarios aportar Tampoco ha gustado que la tan cacareada intervención mejoras a los algoritmos que humana en la ordenación de los resultados no esté ordenan los resultados del buscador. -

Meta Search Engine with an Intelligent Interface for Information Retrieval on Multiple Domains

International Journal of Computer Science, Engineering and Information Technology (IJCSEIT), Vol.1, No.4, October 2011 META SEARCH ENGINE WITH AN INTELLIGENT INTERFACE FOR INFORMATION RETRIEVAL ON MULTIPLE DOMAINS D.Minnie1, S.Srinivasan2 1Department of Computer Science, Madras Christian College, Chennai, India [email protected] 2Department of Computer Science and Engineering, Anna University of Technology Madurai, Madurai, India [email protected] ABSTRACT This paper analyses the features of Web Search Engines, Vertical Search Engines, Meta Search Engines, and proposes a Meta Search Engine for searching and retrieving documents on Multiple Domains in the World Wide Web (WWW). A web search engine searches for information in WWW. A Vertical Search provides the user with results for queries on that domain. Meta Search Engines send the user’s search queries to various search engines and combine the search results. This paper introduces intelligent user interfaces for selecting domain, category and search engines for the proposed Multi-Domain Meta Search Engine. An intelligent User Interface is also designed to get the user query and to send it to appropriate search engines. Few algorithms are designed to combine results from various search engines and also to display the results. KEYWORDS Information Retrieval, Web Search Engine, Vertical Search Engine, Meta Search Engine. 1. INTRODUCTION AND RELATED WORK WWW is a huge repository of information. The complexity of accessing the web data has increased tremendously over the years. There is a need for efficient searching techniques to extract appropriate information from the web, as the users require correct and complex information from the web. A Web Search Engine is a search engine designed to search WWW for information about given search query and returns links to various documents in which the search query’s key words are found. -

SEO - What Are the BIG Things to Get Right? Keyword Research – You Must Focus on What People Search for - Not What You Want Them to Search For

Search Engine Optimization SEO - What are the BIG things to get right? Keyword Research – you must focus on what people search for - not what you want them to search for. Content – Extremely important - #2. Page Title Tags – Clearly a strong contributor to good rankings - #3 Usability – Obviously search engine robots do not know colors or identify a ‘call to action’ statement (which are both very important to visitors), but they do see broken links, HTML coding errors, contextual links between pages and download times. Links – Numbers are good; but Quality, Authoritative, Relevant links on Keyword-Rich anchor text will provide you the best improvement in your SERP rankings. #1 Keyword Research: The foundation of a SEO campaign is accurate keyword research. When doing keyword research: Speak the user's language! People search for terms like "cheap airline tickets," not "value-priced travel experience." Often, a boring keyword is a known keyword. Supplement brand names with generic terms. Avoid "politically correct" terminology. (example: use ‘blind users’ not ‘visually challenged users’). Favor legacy terms over made-up words, marketese and internal vocabulary. Plural verses singular form of words – search it yourself! Keywords: Use keyword search results to select multi-word keyword phrases for the site. Formulate Meta Keyword tag to focus on these keywords. Google currently ignores the tag as does Bing, however Yahoo still does index the keyword tag despite some press indicating otherwise. I believe it still is important to include one. Why – what better place to document your work and it might just come back into vogue someday. List keywords in order of importance for that given page. -

Google and the Digital Divide CHANDOS INTERNET SERIES

Google and the Digital Divide CHANDOS INTERNET SERIES Chandos’ new series of books are aimed at all those individuals interested in the internet. They have been specially commissioned to provide the reader with an authoritative view of current thinking. If you would like a full listing of current and forthcoming titles, please visit our website www.chandospublishing.com or email [email protected] or telephone +44 (0) 1223 891358. New authors: we are always pleased to receive ideas for new titles; if you would like to write a book for Chandos, please contact Dr Glyn Jones on email [email protected] or telephone number +44 (0) 1993 848726. Bulk orders: some organisations buy a number of copies of our books. If you are interested in doing this, we would be pleased to discuss a discount. Please email [email protected] or telephone +44 (0) 1223 891358. Google and the Digital Divide The bias of online knowledge ELAD SEGEV Chandos Publishing Oxford • Cambridge • New Delhi Chandos Publishing TBAC Business Centre Avenue 4 Station Lane Witney Oxford OX28 4BN UK Tel: +44 (0) 1993 848726 Email: [email protected] www.chandospublishing.com Chandos Publishing is an imprint of Woodhead Publishing Limited Woodhead Publishing Limited Abington Hall Granta Park Great Abington Cambridge CB21 6AH UK www.woodheadpublishing.com First published in 2010 ISBN: 978 1 84334 565 7 © Elad Segev, 2010 British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data. A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior written permission of the Publishers. -

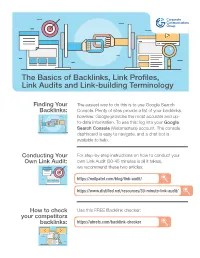

The Basics of Backlinks, Link Profiles, Link Audits and Link-Building Terminology

The Basics of Backlinks, Link Profiles, Link Audits and Link-building Terminology Finding Your The easiest way to do this is to use Google Search Backlinks: Console. Plenty of sites provide a list of your backlinks, however, Google provides the most accurate and up- to-date information. To use this: log into your Google Search Console (Webmasters) account. The console dashboard is easy to navigate, and a chat bot is available to help. Conducting Your For step-by-step instructions on how to conduct your Own Link Audit: own Link Audit (30-45 minutes is all it takes), we recommend these two articles: https://neilpatel.com/blog/link-audit/ https://www.distilled.net/resources/30-minute-link-audit/ How to check Use this FREE Backlink checker: your competitors backlinks: https://ahrefs.com/backlink-checker Link-building Terminology Anchor text • The anchor text, link label, link text, or link title is the Domain Authority (DA) • A search engine ranking score (on visible (appears highlighted) clickable text in a hyperlink. The words a scale of 1 to 100, with 1 being the worst, 100 being the best), contained in the anchor text can influence the ranking that the page developed by Moz that predicts how well a website will rank on will receive by search engines. search engine results pages (SERP’s). Domain Authority is calculated by evaluating multiple factors, including linking root domains and Alt Text (alternative text) • Word or phrase that can be inserted the number of total links, into a single DA score. Domain authority as an attribute in an HTML document to tell website viewers the determines the value of a potential linking website.