The Indonesian Economy During the Japanese Occupation1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gary and Inggriani Shapiro Birthday and Yoga Ecotour

Gary and Inggriani Shapiro Birthday and Yoga Ecotour TRAVEL TYPE EXPEDITION GRADE DURATION ACCOMMODATION Small group of up to 10 Easy to moderate in parts 14 days Local hotels, river boat (klotok), guests - Ages 14 years + (short jungle trekking involved) home stays & jungle lodges Expedition Overview Our many destinations on this special trip are within and between the forests of Central & East Kalimantan (Borneo) where we will see orangutans in their natural environment, visit the local people and witness the change to the rainforest ecosystem. You will be co-hosted by Dr Gary and Inggriani Shapiro, a couple who know orangutans and Indonesia very well. Gary has been studying orangutans for over 46 years and Inggriani is an Indonesian who is a practitioner in the eastern healing arts, including meditation, yoga and massage therapy. Gary is co-hosting this expedition as part of his 70th birthday year celebration. Throughout the expedition, you will be given the opportunity to attend lectures on orangutans and yoga therapy sessions to engage your mind and restore your body. Our first stop is Tanjung Puting National Park where your co-host, Gary, spent time 40+ years ago studying orangutans and helping to rehabilitate ex-captive orangutans. At Camp Leakey, we may come across Tom, the dominant male at the feeding station. We will see both reintroduced and wild orangutans (Pongo pygmaeus wurmbii) as well as a host of other rain forest animals. Page 1 The Tanjung Puting National Park is home to rare and interesting species including the proboscis monkey and the false gavial, a strange looking crocodile. -

Indonesia - Local Charges/Service Fees

Indonesia - Local Charges/Service Fees Charge Tariff Entry: Charge type description English Service or Remarks Currency Fee Unit Effective Date Expiry Date Code RULO (L) Bill of Lading Fee MTD Export IDR 100,000 Electronic SI L006 January 1, 2012 Until further notice Bill of Lading Fee MTD Export IDR 200,000 Manual SI L006 January 1, 2013 Until further notice Administration Fee Origin ADO Export IDR 75,000 per B/L L002 August 1, 2019 April 30, 2020 Administration Fee Origin ADO Export IDR 125,000 per B/L L002 May 1, 2020 Until further notice B/L Amendment Fee MAF Export IDR 350,000 Apply from 2nd Draft L007 August 1, 2019 April 30, 2020 B/L Amendment Fee MAF Export IDR 400,000 Apply from 2nd Draft L007 May 1, 2020 Until further notice B/L Surrender Fee BSF Export IDR 600,000 per B/L L008 December 1, 2016 Until further notice Booking Cancellation Fee BCF Export IDR 200,000 per Booking L001 September 1, 2015 April 30, 2020 Booking Cancellation Fee BCF Export IDR 350,000 per Booking L001 May 1, 2020 Until further notice Invoice Cancellation Fee IAO Export IDR 250,000 per B/L L001 August 1, 2019 April 30, 2020 Invoice Cancellation Fee IAO Export IDR 350,000 per B/L L001 May 1, 2020 Until further notice Certificates Fee CER Export IDR 275,000 per Certificate L018 August 1, 2019 April 30, 2020 Certificates Fee CER Export IDR 300,000 per Certificate L018 May 1, 2020 Until further notice Extra Bills of Lading EBL Export IDR 1,400,000 per B/L L007 October 6, 2017 April 30, 2020 Extra Bills of Lading EBL Export IDR 2,000,000 per B/L L007 May 1, -

Compilation of Manuals, Guidelines, and Directories in the Area of Intellectual Property (Ip) Portfolio Management

DRAFT FOR DISCUSSION COMPILATION OF MANUALS, GUIDELINES, AND DIRECTORIES IN THE AREA OF INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY (IP) PORTFOLIO MANAGEMENT CUSTOMIZED FOR THE ASSOCIATION OF SOUTHEAST ASIAN NATIONS (ASEAN) MEMBER COUNTRIES TABLE OF CONTENTS page 1. Preface…………………………………………………………………. 4 2. Mission Report of Mr. Lee Yuke Chin, Regional Consultant………… 5 3. Overview of ASEAN Companies interviewed in the Study……...…… 22 4. ASEAN COUNTRIES 4. 1. Brunei Darussalam Part I: Listing of Manuals, Guidelines and Directories in the Area of Intellectual Property (IP) Portfolio Management………………………. 39 Part II: Success Stories…………………………………………………. 53 4. 2. Cambodia Part I: Listing of Manuals, Guidelines and Directories in the Area of Intellectual Property (IP) Portfolio Management………………………. 66 Part II: Success Stories…………………………………………………. 85 4. 3. Indonesia Part I: Listing of Manuals, Guidelines and Directories in the Area of Intellectual Property (IP) Portfolio Management………………………. 96 Part II: Success Stories…………………………………………………. 113 4. 4. Lao PDR Part I: Listing of Manuals, Guidelines and Directories in the Area of Intellectual Property (IP) Portfolio Management………………………. 127 Part II: Success Stories…………………………………………………. 144 4. 5. Malaysia Part I: Listing of Manuals, Guidelines and Directories in the Area of Intellectual Property (IP) Portfolio Management………………………. 156 Part II: Success Stories…………………………………………………. 191 4. 6. Myanmar Part I: Listing of Manuals, Guidelines and Directories in the Area of Intellectual Property (IP) Portfolio Management………………………. 213 Part II: Success Stories…………………………………………………. 232 4. 7. Philippines Part I: Listing of Manuals, Guidelines and Directories in the Area of Intellectual Property (IP) Portfolio Management………………………. 248 Part II: Success Stories…………………………………………………. 267 4. 8. Singapore Part I: Listing of Manuals, Guidelines and Directories in the Area of Intellectual Property (IP) Portfolio Management………………………. -

World Bank Document

Document of The World Bank FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY Public Disclosure Authorized Report No: 25720-ID IMPLEMENTATION COMPLETION REPORT (CPL-38540; SCL-3854A; SCPD-3854S; PPFB-P1701) ON A Public Disclosure Authorized LOAN IN THE AMOUNT OF US$136 MILLION TO THE REPUBLIC OF INDONESIA FOR A KALIMANTAN URBAN DEVELOPMENT PROJECT Public Disclosure Authorized June 24, 2003 Urban Development Sector Unit East Asia and Pacific Region This document has a restricted distribution and may be used by recipients only in the performance of their official duties. Its contents may not otherwise be disclosed without World Bank authorization. Public Disclosure Authorized CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (Exchange Rate Effective December 31, 2002) Currency Unit = Rupiah Rp 1 = US$ 0.000112139 US$ 1 = Rp 8,917.50 FISCAL YEAR January 1 December 31 ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS ACSD - Abolition and Combination, Simplification, Decentralization BAPPENAS - National Development Planning Agency BOD - Biochemical Oxygen Demand DPRD - Local Level Parliament EIRR - Economic Internal Rate of Return FIRR - Financial Internal Rate of Return GOI - Government of Indonesia IPLT - Sludge Treatment Facility IUIDP - Integrated Urban Infrastructure Development Program (or Project) KIMPRASWIL - Ministry of Settlements and Regional Infrastructure KIP - Kampung (poor neighborhood) Improvement Program LARAP - Land Acquisition and Resettlement Action Plan LG - Local Government LKMD - Community Organization MIP - Market Improvement Program MOF - Ministry of Finance MSRI - Ministry of Settlement and Regional -

East Kalimantan

PROVINCE INFOGRAPHIC EAST KALIMANTAN Nunukan NUNUKAN Tideng Pale Malinau TANA The boundaries and names shown and the TID UNG designations used on this map do not imply KOTA TARAKAN official endorsement or acceptance by the Tarakan United Nations. MA LINAU BULUNGAN Tanjungselor MOST DENSE LEAST DENSE Tanjung Selor Kota Balikpapan Malinau Tanjungredep MOST POPULATED LEAST POPULATED BERA U Kota Samarinda Tana Tidung 14 1,435 KUTAI DISTRICTS VILLAGES TIMUR Putussibau Sangatta 136 KAPU AS Ujoh Bilang HULU SUB-DISTRICTS Bontang SINTANG KOTA MU RUNG KUTAI BONTANG RAYA KARTANEGARA Legend: Sendawar KOTA SAMARIND A Administrative Boundary Tenggarong Samarinda Samarinda Province Province Capital Purukcahu District District Capital BARITO KUTAI GUNUN G UTARA BARAT MA S Population Transportation Muara Teweh PEN AJAM Population counts at 1km resolution Toll road PA SER Kuala Kurun UTARA KOTA Pasangkayu Primary road 0 BALIKPAPAN Secondary road 1 - 5 Balikpapan Port 6 - 25 Penajam BARITO KATINGAN Airport 26 - 50 SELATAN 51 - 100 Buntok KOTA Other KAPU AS TABALONG PASER 101 - 500 PALANGKA Kasongan Volcano 501 - 2,500 RAYA Tanah Grogot Tamiang Water/Lake 2,501 - 5,000 KOTAWARINGIN Layang Tobadak Tanjung 5,000 - 130,000 TIMUR Palangka Raya BARITO Coastline/River TIMUR Palangkaraya Paringin MA MUJU HULU BALANGAN SUNGAI Amuntai TAPIN UTARA Barabai HULU Sampit SUNGAI KOTA PULANG BARITO HULU SUNGAI Mamuju MA MASA SELATAN TEN GAH BARU GEOGRAPHY PISAU KUALA Mamuju TORA JA East Kalimantan is located at 4°24'N - 2°25'S and 113°44' - 119°00'E. The province borders with Malaysia, specifically Sabah and Sarawak (North), the Sulawesi Ocean and Makasar Straits (East), South Kalimantan (South) and West Kalimantan, Central Kalimantan and Malaysia (West). -

World War II at Sea This Page Intentionally Left Blank World War II at Sea

World War II at Sea This page intentionally left blank World War II at Sea AN ENCYCLOPEDIA Volume I: A–K Dr. Spencer C. Tucker Editor Dr. Paul G. Pierpaoli Jr. Associate Editor Dr. Eric W. Osborne Assistant Editor Vincent P. O’Hara Assistant Editor Copyright 2012 by ABC-CLIO, LLC All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, except for the inclusion of brief quotations in a review, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data World War II at sea : an encyclopedia / Spencer C. Tucker. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-59884-457-3 (hardcopy : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-1-59884-458-0 (ebook) 1. World War, 1939–1945—Naval operations— Encyclopedias. I. Tucker, Spencer, 1937– II. Title: World War Two at sea. D770.W66 2011 940.54'503—dc23 2011042142 ISBN: 978-1-59884-457-3 EISBN: 978-1-59884-458-0 15 14 13 12 11 1 2 3 4 5 This book is also available on the World Wide Web as an eBook. Visit www.abc-clio.com for details. ABC-CLIO, LLC 130 Cremona Drive, P.O. Box 1911 Santa Barbara, California 93116-1911 This book is printed on acid-free paper Manufactured in the United States of America To Malcolm “Kip” Muir Jr., scholar, gifted teacher, and friend. This page intentionally left blank Contents About the Editor ix Editorial Advisory Board xi List of Entries xiii Preface xxiii Overview xxv Entries A–Z 1 Chronology of Principal Events of World War II at Sea 823 Glossary of World War II Naval Terms 831 Bibliography 839 List of Editors and Contributors 865 Categorical Index 877 Index 889 vii This page intentionally left blank About the Editor Spencer C. -

REVIEW Trees of the Balikpapan-Samarinda Area

246 IAWA Journal, Vol. 15 (3), 1994 -----------------... REVIEW Trees of the Balikpapan-Samarinda less this manual focusses on asclection 01' Area, East Kalimantan, Indonesia - a virgin forest species. A volume on the most manual to 280 selected species. Paul J. A. common trec species in secondary forests is Keßler & Kade Sidiyasa, 446 pp., 197 line envisaged as a future complement. drawings, 1994. Tropenbos Se ries 7, The This book compriscs an introductory chap Tropenbos Foundation, Wageningen, The ter with a comprehensive synoptical identifi Netherlands. Distributed by Backhuys Pub cation key on bark and leaf characters, and a lishers, Universal Book Services, P.O Box dichotomous key, also largely based on veg 321, 2300 AH Leiden, The Netherlands. etative features to 210 genera. Keys to spe ISBN 90-5113-019-8. Price: Dfl. 95 (paper cies precede descriptive treatments of invidual back). genera. The keys in fact treat a much higher Following Polak' s acclaimed book on the proportion of the taxa than the 280 species of 83 most common timber tree species of Guy which detailed morphological descriptions are ana (reviewed in IAW A 1. 14: 62), the Tro included in the book. Of 197 species fine line penbos Foundation has now published a Tree drawings emphasising leaf features and fruits Manual on not less than 280 species of the by Mr. Priyono, a talented botanical artist, are Balikpapan-Samarinda Area of East Kaliman included. Most descriptions are followed by tan, Indonesia. The Balikpanan-Samarinda notes on habitat and ecology, uscs, and distri area surrounds the Tropenbos research sitc bution. -

A History of Labor in the Oil Town of the Netherlands-Indie, 1890-1939

Jurnal Sejarah. Vol. 1(2), 2018: 1 – 24 © Pengurus Pusat Masyarakat Sejarawan Indonesia JOSHUA/DOI: 10.26639/js.vi2.62 Worker’s Paradise: A History of Labor in the Oil Town of the Netherlands-Indie, 1890-1939 Norman Joshua Northwestern University [email protected] Abstract This article offers a preliminary survey on the working conditions of laborers in the petroleum industry in late-colonial Netherlands East Indies (1890-1939). Through an examination of the material conditions of work in the oil cities of Pangkalan Brandan, Balikpapan, and Palembang, this article argues that working conditions were substantially influenced by the idiosyncratic characteristics of the petroleum industry, consequently arguing against the current established literature on labor history in Indonesia. By emphasizing on these industrial characteristics and paying attention to its fluctuations, this article offers a more nuanced perspective on the issue of colonial labor regimes. Keywords: labor history, petroleum industry, Netherlands Indies Jurnal Sejarah – Vol. 1/2 (2018): 1-24 | 2 “If an employer is as the trunk to a tree, then his employees are that tree’s branches— and what is a tree without its branches?”1 Sir Henri W.A. Deterding, Chairman, Royal Dutch Shell Group, 1900-1936 Introduction In the 1927 edition of their annual reports (verslagen), the Netherlands East Indies Labor Office (Kantoor van Arbeid) stated the following on the labor conditions in the South Sumatran trading city of Palembang: “[The fact that] petroleum companies can -

Data Rumah Makan Kota Balikpapan

DATA RUMAH MAKAN KOTA BALIKPAPAN NAMA BIDANG USAHA NO NAMA TEMPAT USAHA ALAMAT / NO TELP 1 2 3 1 RM Makan Baruna Jl.Kilo 4,5 Simpang 3 (0542) 861861 2 RM. Ayam Penyet Surya Jl.MT.Haryono Komplek Balikpapan Baru BB C/ 1c (0542)875739 3 RM. Bebek Goreng Jl. Jend.Sudirman 4 RM. Ibu Syarifah Jl. Jend.Sudirman(085250574980) 5 RM.Ampera Bunda Jl.Marsma Iswahyudi RT.005 No.04 (0542)7229512 6 RM.Armin( Mie Aceh) Jl.Ruhui Rahayu No.10 (0542)7124260 7 RM.Atomik Jl. APT.Pranoto 8 RM.Awak Juo Jl.MT.Haryono RT.60 No.75 9 RM.Awliya Pandan Barat 10 RM.Ayam Penyet Ria Jl. Jend.Sudirman Markoni (0542) 8060688 11 RM.Bakso Solo MT.Haryono Balikpapan Baru 12 RM.Batakan Line Jl.Mulawarman No.10 RT.05 (0542)770535 13 RM.Bayar Indah Jl.Letjen Soeprapto RT.7 No.10 14 RM.Blambangan Jl.Marsma Iswahyudi No.15 15 RM.Blitar Jl.Marsma Iswahyudi RT.005 No.04 (0542)762524 16 RM.Boyolali Jl. Jend.Sudirman 17 RM.Bubur Ayam Sawargi Jl.Marsma Iswahyudi (082157813425) 18 RM.Bukit Tinggi Jl.Mulawarman RT.39 (081350514602) 19 RM.Bunaken Balikpapan Baru AB-9 No.05(082158707529) 20 RM.Bunaken Indah Jl. Jend.Sudirman Markoni 21 RM.Bunga Surabaya Blok AA 1A No.06 22 RM.Cita Rasa Balikpapan Baru Blok D1 No.15 ( 0542 ) 872266 23 RM.CV.Artha Bhumi Jl.Marsma Iswahyudi RT.28 (0542) 7031111 24 RM.Dandito Jl.Marsma Iswahyudi 25 RM.Depot Fajar Balikpapan Baru B3 No.19 26 RM.Dimas Ruko Puri Blok 11 Balikpapan Baru 27 RM.Djakarta Pandan Barat RT.16 No.19 (0542)414890 28 RM.Hj.Utari Jl.Perum Graha Indah Blok S/RT.79 No.10 Telp.(0542) 860475 29 RM.Hour Gading Pandan Barat 30 RM.Ibu Ratna Jl.MT.Haryono Komplek Balikpapan Baru RT.84 Simpang 3 BDI 31 RM.Istimewa Balikpapan Baru Blok B1/16 (081347429828) 32 RM.Kairo I Komp.Balikpapan Baru Blok AB 9 No.26 33 RM.Kenari Jl.Marsma Iswahyudi 34 RM.Lembah Anai Jl.Marsma Iswahyudi (0542)771534 35 RM.Lumayan Jl.Kutilang III No.93 RT.23 Telp.081253017436 36 RM.Malinda Jl.Ruhui Rahayu No.7 RT.22 37 RM.Markoni Indah Jl. -

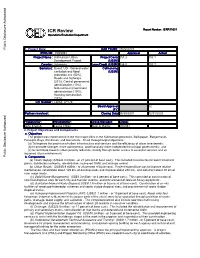

ICR Review Report Number ::: ICRRICRR1163111631 Operations Evaluation Department

ICR Review Report Number ::: ICRRICRR1163111631 Operations Evaluation Department Public Disclosure Authorized 1. Project Data: Date Posted ::: 09/22/2003 PROJ IDID:::: P003951 Appraisal Actual Project Name ::: Kalimantan Urban Project Costs 251.3 153.1 Development Project (((US$M(US$MUS$M)))) Country::: Indonesia LoanLoan////CreditCredit (((US$M(US$MUS$M)))) 136.0 105.7 SectorSector((((ssss):):):): Board: UD - General water Cofinancing sanitation and flood (((US$M(US$MUS$M)))) protection sec (50%), Roads and highways (20%), Central government administration (10%), Sub-national government administration (10%), Housing construction (10%) LLL/L///CC Number::: L3854; LP170 Public Disclosure Authorized Board Approval 02 (((FY(FYFYFY)))) Partners involved ::: Closing Date 06/30/2001 12/31/2002 Prepared by ::: Reviewed by ::: Group Manager ::: GroupGroup:::: John English Laurie Effron Alain A. Barbu OEDST 2. Project Objectives and Components aaa.a... Objectives The project was implemented in the five major cities in the Kalimantan provinces, Balikpapan, Banjarmasin, Palangka Raya, Pontianak, and Samarinda . It had three principal objectives: (a) To improve the provision of urban infrastructure and services and the efficiency of urban investments; (b) to promote stronger, more autonomous, and financially more independent municipal governments; and (c) to contribute towards urban poverty reduction, mainly through better access to essential services and an improved urban environment. Public Disclosure Authorized bbb.b... Components (a) Water Supply; (US$44.0 million - or 21 percent of base cost). This included investments for water treatment plants, distribution networks, rehabilitation, increased O&M, and leakage control; (b) Urban Roads; (US$55.9 million - or 28 percent of base cost). Project expenditure was to improve routine maintenance, rehabilitate about 125 km. -

Aplication the Development of Balikpapan Bay Indonesia Based on Sustainable Tourism

GeoJournal of Tourism and Geosites Year XII, vol. 24, no. 1, 2019, p.29-38 ISSN 2065-0817, E-ISSN 2065-1198 DOI 10.30892/gtg.24103-340 APLICATION THE DEVELOPMENT OF BALIKPAPAN BAY INDONESIA BASED ON SUSTAINABLE TOURISM Syahrul KARIM* Hospitality Department, Balikpapan State Polytechnic Indonesia, 76126, Balikpapan, East Kalimantan, e-mail: [email protected] Bambang Jati KUSUMA Hospitality Department, Balikpapan State Polytechnic Indonesia, 76126, Balikpapan, East Kalimantan, e-mail: [email protected] Tuatul MAHFUD Hospitality Department, Balikpapan State Polytechnic, Indonesia, 76126, Balikpapan, East Kalimantan, e-mail: [email protected] Citation: Karim, S., Kusuma, B. J., & Mahfud, T. (2019). APPLICATION THE DEVELOPMENT OF BALIKPAPAN BAY BASED ON SUSTAINABLE TOURISM. GeoJournal of Tourism and Geosites, 24(1), 29–38. https://doi.org/10.30892/gtg.24103-340 Abstract: The development of sustainable tourism has become an important issue for every country. Although it has been studied extensively, the study of bay tourism development which is in danger of damage is still limited. The purpose of this study is to (1) investigate the picture of tourism potential in Balikpapan Bay; (2) analyze the concept of sustainable tourism development in Balikpapan Bay; (3) examine the direction of sustainable tourism management policies in Balikpapan Bay as a leading tourist destination. The study method uses a mixed method approach. The results of the study revealed that the Balikpapan Bay area has the potential to be an ecotourism-based tourist area with the presence of marine ecosystems, coral reefs, mangrove forests, duyung (mermaid)/ dugong (dugong dugon), and the existence of 250,000 inhabitants of Balikpapan Bay, 80 percent of whom are fishermen. -

CHAPTER 1 5 ABDA and ANZA CN the Second World

CHAPTER 1 5 ABDA AND ANZA C N the second world war the democracies fought at an initial disadvan- Itage, though possessing much greater resources than their enemies . Britain and the United States had embarked on accelerated rearmamen t programs in 1938, the naval projects including battleships and aircraf t carriers ; but this was a delayed start compared with that of Germany an d Japan. Preparing for munitions production for total war, finding out wha t weapons to make, and their perfection into prototypes for mass produc- tion, takes in time upwards of two decades . After this preparation period, a mass production on a nation-wide scale is at least a four-years' task in which "the first year yields nothing ; the second very little ; the third a lot and the fourth a flood" .' When Japan struck in December 1941, Britai n and the British Commonwealth had been at war for more than two years . During that time they had to a large extent changed over to a war economy and increasingly brought reserve strength into play . Indeed, in 1940, 1941 and 1942, British production of aircraft, tanks, trucks, self-propelled gun s and other materials of war, exceeded Germany 's. This was partly due to Britain's wartime economic mobilisation, and partly to the fact that Ger- many had not planned for a long war. Having achieved easy victories b y overwhelming unmobilised enemies with well-organised forces and accumu- lated stocks of munitions and materials, the Germans allowed over- confidence to prevent them from broadening the base of their econom y to match the mounting economic mobilisation of Britain .