6. O Pido Jaber, a Luo Aesthetic Expression Pp103-122

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University of Warwick Institutional Repository

University of Warwick institutional repository: http://go.warwick.ac.uk/wrap A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of Warwick http://go.warwick.ac.uk/wrap/67046 This thesis is made available online and is protected by original copyright. Please scroll down to view the document itself. Please refer to the repository record for this item for information to help you to cite it. Our policy information is available from the repository home page. SOCIAL AND LEGAL CHANGE IN KURIA FAl1ILY RELATIONS Thesis Submitted by Barthazar Aloys RVJEZAURA LL.B (Makerere); LL.M (Harvard) Advocate of the High Court of Tanzania and Senior Lecturer in Law, University of Dar-es-Salaam, Tanzania. In fulfilment of the Requirements for the Award of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy. The University of Warwick, ,School of Law. ,, February, 1982. IMAGING SERVICES NORTH Boston Spa, Wetherby West Yorkshire, LS23 7BQ www.bl.uk BEST COpy AVAILABLE. VARIABLE PRINT QUALITY ii I'ahLeof Contents ii • AcknOi·;~igements v Abstract vii CHAPTER ONE INTRODUCTION 1 - 7 CHAPTER Th'O THE LAND AND PEOPLE Geography and Climate 8 Kuria People and Their History 11 Kuria Social Organisation 13 Kuria Land Tenure 19 CHAPTER 'rHREE HAIN FEATURES OF THE KURIA ECONOHY Introduction 23 Pre-Colonial Agriculture 24 Pre-Colonial Animal Husbandry 29 The Elders' Control of Kuria Economy 38 Summary 41 CHAPTER FOUR THE FORIftATIONOF A PEASANT ECONOMY Introduction 42 Consolidation of Colonial Rule 43 Cash Crop Production 46 Cattle Marketing Policy 53 Import and Export Trade 60 Summary -

Navigating Youth, Generating Adulthood Social Becoming in an African Context

Navigating Youth, Generating Adulthood Social Becoming in an African Context Edited by Catrine Christiansen, Mats Utas and Henrik E. Vigh NORDISKA AFRIKAINSTITUTET, UPPSALA 2006 © The Nordic Africa Institute Indexing terms: Youth Adolescents Children Social environment Living conditions Human relations Social and cultural anthropology Case studies Africa Language checking: Elaine Almén Cover photo: “Sierra Leonean musician 2 Jay” by Mats Utas ISBN 91-7106-578-4 © the authors and Nordiska Afrikainstitutet 2006 Printed in Sweden by Elanders Gotab AB, Stockholm 2006 © The Nordic Africa Institute Contents YOUTH(E)SCAPES Introduction Catrine Christiansen, Mats Utas and Henrik E. Vigh ……………………………………… 9 NAVIGATIng YOUTH Chapter 1. Social Death and Violent Life Chances Henrik E. Vigh ……………………………………………… 31 Chapter 2. Coping with Unpredictability: “Preparing for life” in Ngaoundéré, Cameroon Trond Waage …………………………………………………… 61 Chapter 3. Child Migrants in Transit: Strategies to assert new identities in rural Burkina Faso Dorthe Thorsen ………..……………………………………… 88 GEN(D)ERATIng ADULTHOOD Chapter 4. Popular Music and Luo Youth in Western Kenya: Ambiguities of modernity, morality and gender relations in the era of AIDS Ruth Prince …………...………………………………………… 117 Chapter 5. Industrial Labour, Marital Strategy and Changing Livelihood Trajectories among Young Women in Lesotho Christian Boehm …………………………………………… 153 Chapter 6. Relocation of Children: Fosterage and child death in Biombo, Guinea-Bissau Jónína Einarsdóttir ………………………………………… 183 © The Nordic Africa Institute -

Scripture Translations in Kenya

/ / SCRIPTURE TRANSLATIONS IN KENYA by DOUGLAS WANJOHI (WARUTA A thesis submitted in part fulfillment for the Degree of Master of Arts in the University of Nairobi 1975 UNIVERSITY OF NAIROBI LIBRARY Tills thesis is my original work and has not been presented ior a degree in any other University* This thesis has been submitted lor examination with my approval as University supervisor* - 3- SCRIPTURE TRANSLATIONS IN KENYA CONTENTS p. 3 PREFACE p. 4 Chapter I p. 8 GENERAL REASONS FOR THE TRANSLATION OF SCRIPTURES INTO VARIOUS LANGUAGES AND DIALECTS Chapter II p. 13 THE PIONEER TRANSLATORS AND THEIR PROBLEMS Chapter III p . ) L > THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN TRANSLATORS AND THE BIBLE SOCIETIES Chapter IV p. 22 A GENERAL SURVEY OF SCRIPTURE TRANSLATIONS IN KENYA Chapter V p. 61 THE DISTRIBUTION OF SCRIPTURES IN KENYA Chapter VI */ p. 64 A STUDY OF FOUR LANGUAGES IN TRANSLATION Chapter VII p. 84 GENERAL RESULTS OF THE TRANSLATIONS CONCLUSIONS p. 87 NOTES p. 9 2 TABLES FOR SCRIPTURE TRANSLATIONS IN AFRICA 1800-1900 p. 98 ABBREVIATIONS p. 104 BIBLIOGRAPHY p . 106 ✓ - 4- Preface + ... This is an attempt to write the story of Scripture translations in Kenya. The story started in 1845 when J.L. Krapf, a German C.M.S. missionary, started his translations of Scriptures into Swahili, Galla and Kamba. The work of translation has since continued to go from strength to strength. There were many problems during the pioneer days. Translators did not know well enough the language into which they were to translate, nor could they get dependable help from their illiterate and semi literate converts. -

The Luo People in South Sudan

The Luo People in South Sudan The Luo People in South Sudan: Ethnological Heredities of East Africa By Kon K. Madut The Luo People in South Sudan: Ethnological Heredities of East Africa By Kon K. Madut This book first published 2020 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2020 by Kon K. Madut All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-5743-X ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-5743-7 I would like to dedicate this book to all the Luo People in South Sudan, Ethiopia, Congo, Uganda, Kenya, and Tanzania TABLE OF CONTENTS Author Biography ...................................................................................... ix About this Edition ...................................................................................... xi Acknowledgements ................................................................................. xiii Chapter One ................................................................................................ 1 The Context Background Theoretical Framework Investigating Luo Groups The Construction of Ethnicity and Language Chapter Two ............................................................................................ -

Kenya Briefing Packet

KENYA PROVIDING COMMUNITY HEALTH TO POPULATIONS MOST IN NEED se P RE-FIELD BRIEFING PACKET KENYA 1151 Eagle Drive, Loveland, CO, 80537 | (970) 635-0110 | [email protected] | www.imrus.org KENYA Country Briefing Packet Contents ABOUT THIS PACKET 3 BACKGROUND 4 EXTENDING YOUR STAY? 5 PUBLIC HEALTH OVERVIEW 7 NATIONAL FLAG 15 COUNTRY OVERVIEW 15 OVERVIEW 16 BRIEF HISTORY OF KENYA 17 GEOGRAPHY, CLIMATE AND WEATHER 19 DEMOGRAPHICS 21 ECONOMY 26 EDUCATION 27 RELIGION 29 POVERTY 30 CULTURE 31 USEFUL SWAHILI PHRASES 36 SAFETY 39 CURRENCY 40 IMR RECOMMENDATIONS ON PERSONAL FUNDS 42 TIME IN KENYA 42 EMBASSY INFORMATION 43 WEBSITES 43 !2 1151 Eagle Drive, Loveland, CO, 80537 | (970) 635-0110 | [email protected] | www.imrus.org KENYA Country Briefing Packet ABOUT THIS PACKET This packet has been created to serve as a resource for the KENYA Medical/Dental Team. This packet is information about the country and can be read at your leisure or on the airplane. The first section of this booklet is specific to the areas we will be working near (however, not the actual clinic locations) and contains information you may want to know before the trip. The contents herein are not for distributional purposes and are intended for the use of the team and their families. Sources of the information all come from public record and documentation. You may access any of the information and more updates directly from the World Wide Web and other public sources. !3 1151 Eagle Drive, Loveland, CO, 80537 | (970) 635-0110 | [email protected] | www.imrus.org KENYA Country Briefing Packet BACKGROUND Kenya, located in East Africa, spans more than 224,000 sq. -

Impacts of Colonial Policies and Practices on Kamba Song and Dance up to 1945

IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS) Volume 25, Issue 4, Series. 5 (April. 2020) 18-25 e-ISSN: 2279-0837, p-ISSN: 2279-0845. www.iosrjournals.org Impacts of Colonial Policies and Practices on Kamba Song and dance Up To 1945. Kilonzo Josephine Katiti Abstract: Song and dance are powerful cultural medium in any society. This is especially so in countries where other forms of communication and cultural expression, such as written word are not yet fully developed. The history of many developing countries where colonial domination was evidenced indicates that the colonized people were always able to express themselves through song and dance in complete defiance of the oppressor. Song and dance was used not just as a preserver but also a transmitter of history. This paper seeks to assess the impacts of colonial policies and practices on Kamba song and dance up to 1945. Due to the view of the colonizers that the Africans were primitive and barbaric the colonial masters introduced policies which favored them. These policies led to a definite change of the content of Kamba songs sang at that time. In order to accommodate the changes to the environment, culture, political and economic life of the community, several changes were experienced at the time. This paper present the findings from the study that was conducted on the Kamba of eastern Kenya and shows that over time the community evolved dynamic song and dance styles that responded to the changes within their midst. This paper hopes to contribute to scholarship in terms of the key contribution of Kamba song to the historical transformation of society. -

Race for Distinction a Social History of Private Members' Clubs in Colonial Kenya

Race for Distinction A Social History of Private Members' Clubs in Colonial Kenya Dominique Connan Thesis submitted for assessment with a view to obtaining the degree of Doctor of History and Civilization of the European University Institute Florence, 09 December 2015 European University Institute Department of History and Civilization Race for Distinction A Social History of Private Members' Clubs in Colonial Kenya Dominique Connan Thesis submitted for assessment with a view to obtaining the degree of Doctor of History and Civilization of the European University Institute Examining Board Prof. Stephen Smith (EUI Supervisor) Prof. Laura Lee Downs, EUI Prof. Romain Bertrand, Sciences Po Prof. Daniel Branch, Warwick University © Connan, 2015 No part of this thesis may be copied, reproduced or transmitted without prior permission of the author Race for Distinction. A Social History of Private Members’ Clubs in Colonial Kenya This thesis explores the institutional legacy of colonialism through the history of private members clubs in Kenya. In this colony, clubs developed as institutions which were crucial in assimilating Europeans to a race-based, ruling community. Funded and managed by a settler elite of British aristocrats and officers, clubs institutionalized European unity. This was fostered by the rivalry of Asian migrants, whose claims for respectability and equal rights accelerated settlers' cohesion along both political and cultural lines. Thanks to a very bureaucratic apparatus, clubs smoothed European class differences; they fostered a peculiar style of sociability, unique to the colonial context. Clubs were seen by Europeans as institutions which epitomized the virtues of British civilization against native customs. In the mid-1940s, a group of European liberals thought that opening a multi-racial club in Nairobi would expose educated Africans to the refinements of such sociability. -

Whether a Circumcised Male of the Luo Ethnic Group Would Face

Home > Research > Responses to Information Requests RESPONSES TO INFORMATION REQUESTS (RIRs) New Search | About RIRs | Help 22 June 2005 KEN100286.E Kenya: Whether a circumcised male of the Luo ethnic group would face repercussions from other members of the group and if so, the nature of the these repercussions and the availability of state protection (June 2005) Research Directorate, Immigration and Refugee Board, Ottawa Various sources stated that the Luo people of Kenya do not traditionally practice male circumcision (AIDS Care 1 Feb. 2002; NIAID N.d.; Kenyaspace.com N.d.). However, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) estimates that 10 per cent of Luo adult men are circumcised (N.d.). According to the Kenya Demographic and Health Survey (KDHS), approximately 17 per cent of Luo males between the ages of 15 and 54 are circumcised (Kenya July 1004). However, a March 2004 Epidemiology study stated that circumcision practices differ among denominations as many members of the Luo ethnic group are Christians from African-instituted churches." In a 1 February 2002 study entitled "The Acceptability of Male Circumcision to Reduce HIV Infections in Nyanza Province, Kenya," the authors identified "cultural identification, fear of pain and excessive bleeding and cost" as being some of the primary barriers to acceptance of male circumcision among the Luo (AIDS Care 1 Feb. 2002). However, the results from the same study indicated that "both men and women were eager for promotion of genital hygiene and male circumcision, and they desired availability of circumcision clinical services in the Province's health facilities" (ibid). -

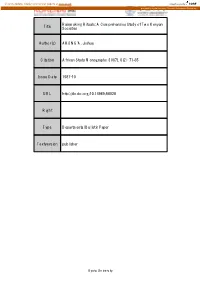

A Comprehensive Study of Two Kenyan Societies Author(S)

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Kyoto University Research Information Repository Rainmaking Rituals: A Comprehensive Study of Two Kenyan Title Societies Author(s) AKONG'A, Joshua Citation African Study Monographs (1987), 8(2): 71-85 Issue Date 1987-10 URL http://dx.doi.org/10.14989/68028 Right Type Departmental Bulletin Paper Textversion publisher Kyoto University African Study "'tonographs, 8(2): 71-85, October 1987 71 RAINMAKING RITUALS: A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF TWO KENYAN SOCIETIES Joshua AKONG'A Instilute ofAfrican Stlldies. Unh'ersity ofNairobi ABSTRACf A comparative examination of the public rainmaking rituals in Kitui District and the secret rainmaking rituals in Bunyore location of Kakamega District, both in Kenya, reveals that public rituals are more susceptible to rapid social change than those of secret. Secondly. although rainmaking rituals are a response to scarcity or unreliability that are rain fall. such rituals can be found even in the areas of adequate rainfall either because the people once lived in an area of rainfall scarcity or the rainmakers are strangers who came from such areas. Thirdly, the efficacy of rainmaking rituals is based on faith, and due to the involvement of the supernatural, they have socio-psychological implications on the participants. Key Words: Rainmaking; Processions; Magic; Prophesy; Occult. INTRODUCTION Sir James George Frazer who wrote widely on the types and practices of magic, considered rainfall rituals as falling under the purview of magic. This is because the purpose of rainfall rituals is to influence weathercondition~ in order to cause rain or to cause drought either for the general good or destruction ofthe people in the specific society in which there is a belief in man's ability to influence weather conditions. -

Ruaha Journal of Arts and Social Sciences (RUJASS), Volume 7, Issue 1, 2021

RUAHA J O U R N A L O F ARTS AND SOCIA L SCIENCE S (RUJASS) Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences - Ruaha Catholic University VOLUME 7, ISSUE 1, 2021 1 Ruaha Journal of Arts and Social Sciences (RUJASS), Volume 7, Issue 1, 2021 CHIEF EDITOR Prof. D. Komba - Ruaha Catholic University ASSOCIATE CHIEF EDITOR Rev. Dr Kristofa, Z. Nyoni - Ruaha Catholic University EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD Prof. A. Lusekelo - Dar es Salaam University College of Education Prof. E. S. Mligo - Teofilo Kisanji University, Mbeya Prof. G. Acquaviva - Turin University, Italy Prof. J. S. Madumulla - Catholic University College of Mbeya Prof. K. Simala - Masinde Murilo University of Science and Technology, Kenya Rev. Prof. P. Mgeni - Ruaha Catholic University Dr A. B. G. Msigwa - University of Dar es Salaam Dr C. Asiimwe - Makerere University, Uganda Dr D. Goodness - Dar es Salaam University College of Education Dr D. O. Ochieng - The Open University of Tanzania Dr E. H. Y. Chaula - University of Iringa Dr E. Haulle - Mkwawa University College of Education Dr E. Tibategeza - St. Augustine University of Tanzania Dr F. Hassan - University of Dodoma Dr F. Tegete - Catholic University College of Mbeya Dr F. W. Gabriel - Ruaha Catholic University Dr M. Nassoro - State University of Zanzibar Dr M. P. Mandalu - Stella Maris Mtwara University College Dr W. Migodela - Ruaha Catholic University SECRETARIAL BOARD Dr Gerephace Mwangosi - Ruaha Catholic University Mr Claudio Kisake - Ruaha Catholic University Mr Rubeni Emanuel - Ruaha Catholic University The journal is published bi-annually by the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, Ruaha Catholic University. ©Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, Ruaha Catholic University. -

South Nyanza Historical Texts Volume I

SOUTH NYANZA HISTORICAL TEXTS VOLUME I THEODORA OLUNGA AYOT THIS TIIERIR FMS Itl'^V A rTEPTKD FOT Tm: d m - » AND A ( - . , pi tu UN 'iUU UaiVKUSITY U ^uAliU UNIVERSITY OF NAIROBI DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY 1076-1978 UNIVERSITY OF NAIROBI LIBRARY 0100157 7 TABLE OF CONTENTS Pag* Introduction 11 CHAPTER 1 JO-KARACHUONYO.................. 1 2 THE HAS I PUL. i.................. 43 3 THE KABONDO. .1................. 71 \ 4 KANYADA.......................... 05 5 JO-KOCBIA........................ 121 \ 6 THE KAGAN........................ 140 7 JO-GEM........................... 140 8 KANYAMWA......................... 160 0 THE KARUNGU..................... 172 10 KADEM............................ 102 11 KWABWAI, KANYADOTO fc KANYIKELA... 200 12 JO-KAMAGAMBO.................... 230 , 13 THE KANYAMKAGO.................. 256 14 JO-SAKWA......................... 264 15 JO-KOGELO..... ............... 282 16 JO-ALEGO......................... 306 17 JO-CHULA......................... 341 i / ,1 Introduction South Nyanza Historical Texts consists of the material collected during 1976-1978 field research. The research was conducted among the people of Kanyamwa, Kabuoch, Karungu, Kadera, Kwa- bwai, Kanyadoto, Kanyikela, Kanyada, Kochia, Kagan, Gem, Karachuonyo, Kabondo/Kasipul, Kamagambo, Sakwa, Kanyarakago, Jo-Kogelo, Alego and Jo-Chula. CHAPTER 1 JO-KARACHUONYO Intro due Mo n Tho history of Jo-Karachuonyo is the history of the Southern Luo migrations into Kenya between 1450-1750. Karachuonyo derives its name from 'Rachuonyo* who accord ing to tradition was the ancestor of most of the lineages living here. Roughly it is bordered to the south by Jok- O.iiolo group of Kochia, Kagan and Gem, To the South east are the Gusli and Kipsigis peoples respectively and to north is Nyakach and the rest of the ..rta is bordered by Nyanza Gulf. -

Journal of Arts & Humanities

Journal of Arts & Humanities Volume 07, Issue 11, 2018: 58-67 Article Received: 06-09-2018 Accepted: 02-10-2018 Available Online: 23-11-2018 ISSN: 2167-9045 (Print), 2167-9053 (Online) DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.18533/journal.v7i10.1491 Pioneering a Pop Musical Idiom: Fifty Years of the Benga Lyrics 1 in Kenya Joseph Muleka2 ABSTRACT Since the fifties, Kenya and Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) have exchanged cultural practices, particularly music and dance styles and dress fashions. This has mainly been through the artistes who have been crisscrossing between the two countries. So, when the Benga musical style developed in the sixties hitting the roof in the seventies and the eighties, contestations began over whether its source was Kenya or DRC. Indeed, it often happens that after a musical style is established in a primary source, it finds accommodation in other secondary places, which may compete with the originators in appropriating the style, sometimes even becoming more committed to it than the actual primary originators. This then begins to raise debates on the actual origin and/or ownership of the form. In situations where music artistes keep shuttling between the countries or regions like the Kenya and DRC case, the actual origin and/or ownership of a given musical practice can be quite blurred. This is perhaps what could be said about the Benga musical style. This paper attempts to trace the origins of the Benga music to the present in an effort to gain clarity on a debate that has for a long time engaged music pundits and scholars.