Fare4all? Report of the Enquiry Into Public Transport in Glasgow

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Open Space Strategy Consultative Draft

GLASGOW OPEN SPACE STRATEGY CONSULTATIVE DRAFT Prepared For: GLASGOW CITY COUNCIL Issue No 49365601 /05 49365601 /05 49365601 /05 Contents 1. Executive Summary 1 2. Glasgu: The Dear Green Place 11 3. What should open space be used for? 13 4. What is the current open space resource? 23 5. Place Setting for improved economic and community vitality 35 6. Health and wellbeing 59 7. Creating connections 73 8. Ecological Quality 83 9. Enhancing natural processes and generating resources 93 10. Micro‐Climate Control 119 11. Moving towards delivery 123 Strategic Environmental Assessment Interim Environment Report 131 Appendix 144 49365601 /05 49365601 /05 1. Executive Summary The City of Glasgow has a long tradition in the pursuit of a high quality built environment and public realm, continuing to the present day. This strategy represents the next steps in this tradition by setting out how open space should be planned, created, enhanced and managed in order to meet the priorities for Glasgow for the 21st century. This is not just an open space strategy. It is a cross‐cutting vision for delivering a high quality environment that supports economic vitality, improves the health of Glasgow’s residents, provides opportunities for low carbon movement, builds resilience to climate change, supports ecological networks and encourages community cohesion. This is because, when planned well, open space can provide multiple functions that deliver numerous social, economic and environmental benefits. Realising these benefits should be undertaken in a way that is tailored to the needs of the City. As such, this strategy examines the priorities Glasgow has set out and identifies six cross‐cutting strategic priority themes for how open space can contribute to meeting them. -

Bus Operator Alliance Contents

Glasgow City Region — Bus Operator Alliance Contents Introducing the alliance 3 What do bus users want? 4 What will we do? 7 We will commit to… 8 What do we need local authorities to do? 9 Buses at the heart of our communities 10 Operator Vision Post Covid journey — considerations 12 The key shared deliverables: 15 Customer service 16 Network coverage 17 Journey speed and reliability 18 Fares and ticketing 19 Environment 20 Information and facilities 22 2 The main bus operators across the Glasgow City region Introducing have come together to set out our vision for Bus the alliance The alliance currently includes; City Sightseeing — Glasgow First Glasgow First Midland Glasgow Citybus JMB Travel McGill’s Stagecoach East Scotland Stagecoach West Scotland Whitelaw’s An invitation will be sent to every other bus operator who serves the Glasgow City Region to get on board with the vision for buses and bus-users 3 • Good service with seamless connections from every part of the transport system What do bus • R eliable travel not affected by congestion or roadworks users want? • A modern and convenient ticketing system that is affordable and easy to use • A consistent and easy to use journey planning and information system • M odern, clean and well presented vehicles with safe and secure bus stops, bus stations and hubs with up-to-date travel info • Clear and simple communications • To have their voice heard and action to feedback 4 6 • We will set out our vision in a report called ‘Successful Buses for a Successful What will City Region’ by the end of April 2021. -

PA031 NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde

PA031 NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde Preventative Agenda Inquiry 1. Which areas of preventative spending/ the preventative agenda would it be most useful for the Health and Sport Committee to investigate? The Health and Sport Committee should be clear about its definition of prevention and preventative spend as part of the investigatory framework and provide further clarity on the use and understanding of the terms nationally. The investigation should consider the ability to reduce inequalities and tackle social determinants as a primary consideration for preventative activity. Prevention should include; systems prevention (access / environment); population prevention (skills/ values/social norms); targeted prevention (vulnerability) and early stage prevention approaches (early intervention). Prevention is actions which prevent avoidable premature mortality or improve healthy life expectancy and reduce inequalities in both. There are three levels of preventative action: 1. Primary Prevention – action before any health harm has arisen 2. Secondary Prevention – early intervention to catch and reverse or mitigate health harm at an early stage. 3. Tertiary Prevention – once health harm established to prevent further deterioration. There are also three axes of preventative action – Upstream/Downstream, regulatory/requiring individual opt-in, universal/proportionate/targeted. The upstream/downstream axes refers to the continuum between fundamental causes through intermediate to immediate causes of ill health/loss of wellbeing represented through the adapted Health Scotland Model below: 1 PA031 Upstream Downstre Fundamental Intermediate Imme Causes Causes Cau Political priorities, Education Damp h decisions and Economy & Work Hazardo societal values Social &cultural Adverse li Leading to: services Personal s Unequal distributionLifestyle Physical Drift and vulne of income, resource Environment Behav and power There is evidence1,2 that action which is more upstream, regulatory and proportionate is the most effective and cost-effective at achieving the above aims. -

Overview of Allocated Funding

Overview of allocated funding A combined total of £979,625 has been awarded to 116 community groups and workplaces through the Cycling Friendly programme with a further £821,991 awarded to registered social landlords across Scotland for improvement facilities to promote walking and cycling. More than 90,000 people will benefit from the funding. Setting Number funded Amount funded People impacted Community groups 48 £536,737 Data not collected Employers 68 £442,888 27,500 Social housing 33 £821,991 62,119 providers Total 149 £1,801,616 89,619 Kath Brough, Head of Behaviour Change at Cycling Scotland said: “We’re delighted to announce funding to 149 organisations across Scotland to encourage more people to cycle. Cycling Scotland work closely with partners to help employers, community groups and housing associations take advantage of the benefits of cycling and this round of funding will provide opportunity for over 90,000 people across Scotland to access improved cycling facilities.” Elderbank Housing Association, based in Govan, Glasgow, will receive £25,000 to install cycle parking for the 2,700 residents living across their properties, where currently there is no cycle parking. Jim Fraser, Estate Management Inspector, said “lack of storage has been a key issue for residents, especially those in older tenement buildings, so installing bike parking will remove a significant barrier to the uptake in bike ownership and cycling as a healthy activity. Govan is well established as an area of high deprivation and residents can often be found to have low household income and higher levels of household debt. This can impact greatly on people’s ability to access public transport beyond a limited geographical area and frequency due to a lack of sufficient finance. -

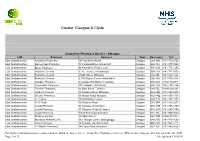

Greater Glasgow & Clyde

Greater Glasgow & Clyde Smokefree Pharmacy Service - Glasgow CHP Pharmacy Address 1 Town Post code Tel East Dunbartonshire Auchinairn Pharmacy 167 Auchinairn Road Glasgow G64 1NG 0141-772-2752 East Dunbartonshire Bannermans Pharmacy 75 Merkland Drive, Kirkintilloch Glasgow G66 3SJ 0141-777-7224 East Dunbartonshire Boots Pharmacy 92 Kirkintilloch Road, Lenzie Glasgow G66 4LQ 0141-776-1202 East Dunbartonshire Boots the Chemist 3 The Triangle, Bishopbriggs Glasgow G64 2TR 0141-772-0070 East Dunbartonshire Boots the Chemist 6 Main Street, Milngavie Glasgow G62 6BL 0141-956-1241 East Dunbartonshire Boots the Chemist 9, The Regent Centre, Kirkintilloch Glasgow G66 1JH 0141-776-3418 East Dunbartonshire Campsie Pharmacy 6 Campsie Rd, Milton of Campsie Glasgow G66 8EA 01360 312389 East Dunbartonshire Cooperative Pharmacy 101 Cowgate, Kirkintilloch Glasgow G66 1JD 0141-776-1264 East Dunbartonshire Torrance Pharmacy 63 Main Street, Torrance Glasgow G64 4EL 01360 620 291 East Dunbartonshire Gordons Chemist 16 Douglas Street, Milngavie Glasgow G62 6PB 0141-956-5235 East Dunbartonshire Graeme Pharmacy 33 Station Road, Milngavie Glasgow G62 8PQ 0141-956-1710 East Dunbartonshire J F Forbes 193 Kirkintilloch Road Glasgow G64 2LS 0141-772-1771 East Dunbartonshire J H C Suttie 104 Drymen Road Glasgow G61 3RA 0141-942-0274 East Dunbartonshire Lloyds Pharmacy 56 Cowgate, Kirkintilloch Glasgow G66 1HN 0141-776-1950 East Dunbartonshire Lloyds Pharmacy 57 Milngavie Road, Bearsden Glasgow G61 2DW 0141-943-1086 East Dunbartonshire Lloyds Pharmacy 8 New Kirk Road, -

East Renfrewshire Profile Cite This Report As: Shipton D and Whyte B

East Renfrewshire Profile Cite this report as: Shipton D and Whyte B. Mental Health in Focus: a profile of mental health and wellbeing in Greater Glasgow & Clyde. Glasgow: Glasgow Centre for Population Health, 2011. www.GCPH.co.uk/mentalhealthprofiles Acknowledgements Thanks to those who kindly provided data and/or helped with the interpretation: Judith Brown (Scottish Observatory for Work and Health, University of Glasgow), Anna Cameron (Labour Market Statistics, Scottish Government), Jan Cassels (Scottish Health Survey, Scottish Government), Louise Flanagan (NHS Health Scotland), Julie Kidd (ISD Scotland), Stuart King (Scottish Crime & Justice Survey, Scottish Government), Nicolas Krzyzanowski (Scottish Household Survey, Scottish Government), Rebecca Landy (Scottish Health Survey, Scottish Government), Will Linden (Violence Reduction Unit, Strathclyde Police), Carole Morris (ISD Scotland), David McLaren (Scottish House Condition Survey, Scottish Government), Carol McLeod (formally Violence Reduction Unit, Strathclyde Police), Denise Patrick (Labour Market Statistics, Scottish Government), the PsyCIS Steering Group (Mental Health Services, NHS GG&C), Julie Ramsey (Scottish Health Survey, Scottish Government), David Scott (ISD Scotland), Martin Taulbut (NHS Health Scotland), Gordon Thomson (ISD Scotland), Elaine Tod (NHS Health Scotland), Susan Walker (Housing and Household Surveys, The Scottish Government), National Records for Scotland. We would like to also thank the steering group for their invaluable input during the project: Doug -

Tizard Learning Disability Review Emerald Article: Deinstitutionalisation and Community Services in Greater Glasgow John Dalrymple

Tizard Learning Disability Review Emerald Article: Deinstitutionalisation and Community Services in Greater Glasgow John Dalrymple Article information: To cite this document: John Dalrymple, (1999),"Deinstitutionalisation and Community Services in Greater Glasgow", Tizard Learning Disability Review, Vol. 4 Iss: 1 pp. 13 - 23 Permanent link to this document: http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/13595474199900004 Downloaded on: 22-05-2012 To copy this document: [email protected] This document has been downloaded 136 times. Access to this document was granted through an Emerald subscription provided by For Authors: If you would like to write for this, or any other Emerald publication, then please use our Emerald for Authors service. Information about how to choose which publication to write for and submission guidelines are available for all. Additional help for authors is available for Emerald subscribers. Please visit www.emeraldinsight.com/authors for more information. About Emerald www.emeraldinsight.com With over forty years' experience, Emerald Group Publishing is a leading independent publisher of global research with impact in business, society, public policy and education. In total, Emerald publishes over 275 journals and more than 130 book series, as well as an extensive range of online products and services. Emerald is both COUNTER 3 and TRANSFER compliant. The organization is a partner of the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) and also works with Portico and the LOCKSS initiative for digital archive preservation. *Related content and download information correct at time of download. •••SERVICE FEATURE Deinstitutionalisation and Community Services in Greater Glasgow ABSTRACT Knowledge of what makes for quality in adult learning disabilities services does not cascade directly down into grassroots practice. -

New Stobhill Hospital the New Stobhill Ambulatory Care Hospital Belmont (ACH) Is Set in the Stobhill Campus

To Bishopbriggs FIF New Stobhill station E WAY New Stobhill Hospital The New Stobhill Ambulatory Care Hospital Belmont (ACH) is set in the Stobhill campus. The campus Hospital D Centre A O houses the hospital, a minor injuries unit, a R L L Marie Curie number of general and specialist mental health Walking and cycling guide 2021 HI Hospice Y facilities, and a brand new purpose-built Marie RA G Curie Cancer Care hospice. L BA A LORNOCK ROAD B The ACH provides outpatient clinics, day surgery and diagnostic services. There are hospital beds available to medics to extend the range of short B ALORNOCK ROAD stay surgical procedures offered to patients. B A L Skye House O At the main entrance there is a staffed help desk R N O and patient information points which provide C K R travel information, health promotion and other O A D advice. BELMONT ROAD Stobhill Hospital 2 new mental health wards are now on the campus. The two wards – Elgin and Appin – have space for up to 40 inpatients, with Elgin To Springburn dedicated to adult acute mental health inpatient station care and Appin focusing on older adults with functional mental health issues. Cycle Parking Entrance Rowanbank Bus stop Clinic BALORNOCK ROAD Active Travel Cycling to Work NHS Greater Glasgow & Clyde recognise that New Stobhill Hospital is well served by public transport The Cycle to Work scheme is a salary sacrifice scheme physical activity is essential for good health covering bus travel within the immediate area and available to NHS Greater Glasgow & Clyde staff*. -

Glasgow City Integration Joint Board Assessment Report

Public Records (Scotland) Act 2011 Glasgow City Integration Joint Board The Keeper of the Records of Scotland 19th March 2021 A32398043 - NRS - Public Records (Scotland) Act (PRSA) - Integration Joint Board Glasgow City - Agreement Report 1 Assessment Report Contents 1. Public Records (Scotland) Act 2011 3 2. Executive Summary 4 3. Authority Background 4 4. Assessment Process 5 5. Model Plan Elements: Checklist 6 6. Keeper’s Summary 24 7. Keeper’s Determination 24 8. Keeper's Endorsement 25 National Records of Scotland 2 Assessment Report 1. Public Records (Scotland) Act 2011 The Public Records (Scotland) Act 2011 (the Act) received Royal assent on 20 April 2011. It is the first new public records legislation in Scotland since 1937 and came fully into force on 1 January 2013. Its primary aim is to promote efficient and accountable record keeping by named Scottish public authorities. The Act has its origins in The Historical Abuse Systemic Review: Residential Schools and Children’s Homes in Scotland 1950-1995 (The Shaw Report) published in 2007. The Shaw Report recorded how its investigations were hampered by poor record keeping and found that thousands of records had been created, but were then lost due to an inadequate legislative framework and poor records management. Crucially, it demonstrated how former residents of children’s homes were denied access to information about their formative years. The Shaw Report demonstrated that management of records in all formats (paper and electronic) is not just a bureaucratic process, but central to good governance and should not be ignored. A follow-up review of public records legislation by the Keeper of the Records of Scotland (the Keeper) found further evidence of poor records management across the public sector. -

East Renfrewshire

A Community Health and Wellbeing Profile for East Renfrewshire February 2008 Published by Glasgow Centre for Population Health Level 6 39 St Vincent Place Glasgow G1 2ER For further information please contact: Bruce Whyte, Glasgow Centre for Population Health Tel: 0141 221 9439 Email: [email protected] Web: www.gcph.co.uk/communityprofiles Contents Introduction 1 Purpose 1 Geographical coverage 2 Content 2 Notes and caveats 4 Local action to improve health and reduce inequalities 5 Evaluation 5 Acknowledgements 5 Web 6 Interpretation 6 Maps 9 Community Health Partnership Area Map 11 Greenspace Map 13 Air Quality Map 15 Trend and Spine Graphs 17 Definitions and Sources 61 A Community Health and Wellbeing Profile for East Renfrewshire Introduction This profile is one of ten new community health and wellbeing profiles that have been compiled by the Glasgow Centre for Population Health (GCPH) for the Greater Glasgow and Clyde NHS Board area. Each profile provides indicators for a range of health outcomes (e.g. life expectancy, mortality, hospitalisation) and health determinants (e.g. smoking levels, breastfeeding, income, employment, crime, education). These profiles build on the success of both the 2004 community health profiles published by NHS Health Scotland (www.scotpho.org.uk/communityprofiles), and of the ‘Let Glasgow Flourish’ report published by GCPH in April 2006 (www.gcph.co.uk/content/view/17/34/). Whilst these sources continue to be useful, there has been recognition of the need for more up-to-date health data and for information pertaining to the new Community Health (and Care) Partnership (CH(C)P) administrative structures. -

You Can View Your New Service 329 Timetable Here

329 NEW TIMETABLE FROM 16 JULY 2017 329 GLASGOW ROYSTON SPRINGBURN SHOPPING CENTRE STOBHILL H www.mcgillsbuses.co.uk Glasgow - Stobhill Hospital H via Royston and Springburn 329 1 MONDAY – FRIDAY from 17 July 2017 Service No. 329 329 329 329 329 329 329 329 329 329 329 329 06.33 07.03 07.33 08.03 08.33 09.03 09.33 10.03 16.33 17.03 17.33 18.03 Glasgow, West Nile Street Then McGill’s GoSmart card is the flexible and Baird Street, Police Station 06.39 07.09 07.39 08.09 08.39 09.09 09.39 10.09 every 16.39 17.09 17.39 18.09 convenient way to pay for your travel. Roystonhill 06.45 07.15 07.45 08.15 08.45 09.15 09.45 10.15 30 16.45 17.15 17.45 18.15 Simply add your GoZone ticket to your card Broomfield Park 06.52 07.22 07.52 08.22 08.52 09.22 09.52 10.22 mins 16.52 17.22 17.52 18.22 online, and activate next time you travel. Springburn Shopping Centre 06.55 07.25 07.55 08.25 08.55 09.25 09.55 10.25 until 16.55 17.25 17.55 18.25 Balgrayhill 06.56 07.26 07.56 08.26 08.56 09.26 09.56 10.26 16.56 17.26 17.56 18.26 n QUICKER BOARDING Stobhill Hospital H 07.00 07.30 08.00 08.30 09.00 09.30 10.00 10.30 17.00 17.30 18.00 18.30 n NO NEED FOR A PAPER TICKET OR TO CARRY CASH MONDAY – FRIDAY from 17 July 2017 n JUST TAP & GO! Service No. -

Integration Scheme Between Glasgow City Council and NHS Greater

Integration Scheme Between Glasgow City Council and NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde December 2015 Page 1 of 60 1. Introduction 1.1 The Public Bodies (Joint Working) (Scotland) Act 2014 (the Act) requires Health Boards and Local Authorities to integrate planning for, and delivery of, certain adult health and social care services. They can also choose to integrate planning and delivery of other services – additional adult health and social care services, such as Homelessness and Criminal Justice, beyond the minimum prescribed by Ministers, and children’s health and social care services. The Act requires them to prepare jointly an integration scheme setting out how this joint working is to be achieved. There is a choice of ways in which they may do this: the Health Board and Council can either delegate between each other (under s1(4(b), (c) and (d) of the Act), or can both delegate to a third body called the Integration Joint Board (under s1(4)(a) of the Act). Delegation between the Health Board and Council is commonly referred to as a “lead agency” arrangement. Delegation to an Integration Joint Board is commonly referred to as a “body corporate” arrangement. 1.2 This document sets out the integration arrangements adopted by NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde and Glasgow City Council, as required by Section 7 of the Act. This integration scheme follows the format of the model document produced by the Scottish Government, and includes all matters prescribed in Regulations. 1.3 Once the integration scheme has been approved by the Scottish Ministers, the Integration Joint Board (which has distinct legal personality) will be established by Order of the Scottish Ministers.