PA031 NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bus Operator Alliance Contents

Glasgow City Region — Bus Operator Alliance Contents Introducing the alliance 3 What do bus users want? 4 What will we do? 7 We will commit to… 8 What do we need local authorities to do? 9 Buses at the heart of our communities 10 Operator Vision Post Covid journey — considerations 12 The key shared deliverables: 15 Customer service 16 Network coverage 17 Journey speed and reliability 18 Fares and ticketing 19 Environment 20 Information and facilities 22 2 The main bus operators across the Glasgow City region Introducing have come together to set out our vision for Bus the alliance The alliance currently includes; City Sightseeing — Glasgow First Glasgow First Midland Glasgow Citybus JMB Travel McGill’s Stagecoach East Scotland Stagecoach West Scotland Whitelaw’s An invitation will be sent to every other bus operator who serves the Glasgow City Region to get on board with the vision for buses and bus-users 3 • Good service with seamless connections from every part of the transport system What do bus • R eliable travel not affected by congestion or roadworks users want? • A modern and convenient ticketing system that is affordable and easy to use • A consistent and easy to use journey planning and information system • M odern, clean and well presented vehicles with safe and secure bus stops, bus stations and hubs with up-to-date travel info • Clear and simple communications • To have their voice heard and action to feedback 4 6 • We will set out our vision in a report called ‘Successful Buses for a Successful What will City Region’ by the end of April 2021. -

Fare4all? Report of the Enquiry Into Public Transport in Glasgow

Fare4All? Report of the Enquiry into Public Transport in Glasgow March 2006 Contents Fare4All? Steering Group 3 Fare4All? Key Findings 4 Fare4All? Suggestions for Improvements 5 1. Fare4All? 6 2. The Work of Fare4All? 7 3. Some Background to Bus Policy and Provision 8 Glasgow – A City Perspective Some Facts on the Communities who need to use Public Transport 4. Key Findings of the Fare4All? Survey 11 5. Perspectives of Older People 13 6. Perspectives of Parents with Children 14 7. Perspectives of People with Learning Disabilities 15 8. The Impact of Transport on Community Life: A Profile of North Glasgow 16 9. Fare4All? Transport Summit 18 10. Suggestions for Improvement 21 11. References 22 2 Fare4All? Steering Group The Fare4All? Steering Group is chaired by Paul Martin MSP. The members are: Allan Comrie Strathclyde Passenger Transport Executive Arlene Cooke North Glasgow Healthy Living Community Frank Creighton Healthy Castlemilk Irene Forrest North Area Transport Association John Halliday Strathclyde Passenger Transport Executive Fran Lundie Glasgow City Council Community Safety Department Agnes McGroarty West of Scotland Seniors’ Forum Niall McGrogan NHS Greater Glasgow Helen McNeil Glasgow Council for Voluntary Services Marie Montgomery Age Concern Jim Thompson Fair Deal Jess Thomson The Friends of the Victoria Kate Munro Community Engagement Manager, NHS Greater Glasgow Dan Harley Community Engagement Manager, NHS Greater Glasgow Mark McAllister Community Engagement Manager, NHS Greater Glasgow The content of this report reflects the views of the Fare4All? Steering Group or individual contributors and not necessarily those of any named organisation. This report is also available in large print and on-line. -

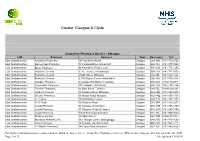

Greater Glasgow & Clyde

Greater Glasgow & Clyde Smokefree Pharmacy Service - Glasgow CHP Pharmacy Address 1 Town Post code Tel East Dunbartonshire Auchinairn Pharmacy 167 Auchinairn Road Glasgow G64 1NG 0141-772-2752 East Dunbartonshire Bannermans Pharmacy 75 Merkland Drive, Kirkintilloch Glasgow G66 3SJ 0141-777-7224 East Dunbartonshire Boots Pharmacy 92 Kirkintilloch Road, Lenzie Glasgow G66 4LQ 0141-776-1202 East Dunbartonshire Boots the Chemist 3 The Triangle, Bishopbriggs Glasgow G64 2TR 0141-772-0070 East Dunbartonshire Boots the Chemist 6 Main Street, Milngavie Glasgow G62 6BL 0141-956-1241 East Dunbartonshire Boots the Chemist 9, The Regent Centre, Kirkintilloch Glasgow G66 1JH 0141-776-3418 East Dunbartonshire Campsie Pharmacy 6 Campsie Rd, Milton of Campsie Glasgow G66 8EA 01360 312389 East Dunbartonshire Cooperative Pharmacy 101 Cowgate, Kirkintilloch Glasgow G66 1JD 0141-776-1264 East Dunbartonshire Torrance Pharmacy 63 Main Street, Torrance Glasgow G64 4EL 01360 620 291 East Dunbartonshire Gordons Chemist 16 Douglas Street, Milngavie Glasgow G62 6PB 0141-956-5235 East Dunbartonshire Graeme Pharmacy 33 Station Road, Milngavie Glasgow G62 8PQ 0141-956-1710 East Dunbartonshire J F Forbes 193 Kirkintilloch Road Glasgow G64 2LS 0141-772-1771 East Dunbartonshire J H C Suttie 104 Drymen Road Glasgow G61 3RA 0141-942-0274 East Dunbartonshire Lloyds Pharmacy 56 Cowgate, Kirkintilloch Glasgow G66 1HN 0141-776-1950 East Dunbartonshire Lloyds Pharmacy 57 Milngavie Road, Bearsden Glasgow G61 2DW 0141-943-1086 East Dunbartonshire Lloyds Pharmacy 8 New Kirk Road, -

East Renfrewshire Profile Cite This Report As: Shipton D and Whyte B

East Renfrewshire Profile Cite this report as: Shipton D and Whyte B. Mental Health in Focus: a profile of mental health and wellbeing in Greater Glasgow & Clyde. Glasgow: Glasgow Centre for Population Health, 2011. www.GCPH.co.uk/mentalhealthprofiles Acknowledgements Thanks to those who kindly provided data and/or helped with the interpretation: Judith Brown (Scottish Observatory for Work and Health, University of Glasgow), Anna Cameron (Labour Market Statistics, Scottish Government), Jan Cassels (Scottish Health Survey, Scottish Government), Louise Flanagan (NHS Health Scotland), Julie Kidd (ISD Scotland), Stuart King (Scottish Crime & Justice Survey, Scottish Government), Nicolas Krzyzanowski (Scottish Household Survey, Scottish Government), Rebecca Landy (Scottish Health Survey, Scottish Government), Will Linden (Violence Reduction Unit, Strathclyde Police), Carole Morris (ISD Scotland), David McLaren (Scottish House Condition Survey, Scottish Government), Carol McLeod (formally Violence Reduction Unit, Strathclyde Police), Denise Patrick (Labour Market Statistics, Scottish Government), the PsyCIS Steering Group (Mental Health Services, NHS GG&C), Julie Ramsey (Scottish Health Survey, Scottish Government), David Scott (ISD Scotland), Martin Taulbut (NHS Health Scotland), Gordon Thomson (ISD Scotland), Elaine Tod (NHS Health Scotland), Susan Walker (Housing and Household Surveys, The Scottish Government), National Records for Scotland. We would like to also thank the steering group for their invaluable input during the project: Doug -

Tizard Learning Disability Review Emerald Article: Deinstitutionalisation and Community Services in Greater Glasgow John Dalrymple

Tizard Learning Disability Review Emerald Article: Deinstitutionalisation and Community Services in Greater Glasgow John Dalrymple Article information: To cite this document: John Dalrymple, (1999),"Deinstitutionalisation and Community Services in Greater Glasgow", Tizard Learning Disability Review, Vol. 4 Iss: 1 pp. 13 - 23 Permanent link to this document: http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/13595474199900004 Downloaded on: 22-05-2012 To copy this document: [email protected] This document has been downloaded 136 times. Access to this document was granted through an Emerald subscription provided by For Authors: If you would like to write for this, or any other Emerald publication, then please use our Emerald for Authors service. Information about how to choose which publication to write for and submission guidelines are available for all. Additional help for authors is available for Emerald subscribers. Please visit www.emeraldinsight.com/authors for more information. About Emerald www.emeraldinsight.com With over forty years' experience, Emerald Group Publishing is a leading independent publisher of global research with impact in business, society, public policy and education. In total, Emerald publishes over 275 journals and more than 130 book series, as well as an extensive range of online products and services. Emerald is both COUNTER 3 and TRANSFER compliant. The organization is a partner of the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) and also works with Portico and the LOCKSS initiative for digital archive preservation. *Related content and download information correct at time of download. •••SERVICE FEATURE Deinstitutionalisation and Community Services in Greater Glasgow ABSTRACT Knowledge of what makes for quality in adult learning disabilities services does not cascade directly down into grassroots practice. -

Glasgow City Integration Joint Board Assessment Report

Public Records (Scotland) Act 2011 Glasgow City Integration Joint Board The Keeper of the Records of Scotland 19th March 2021 A32398043 - NRS - Public Records (Scotland) Act (PRSA) - Integration Joint Board Glasgow City - Agreement Report 1 Assessment Report Contents 1. Public Records (Scotland) Act 2011 3 2. Executive Summary 4 3. Authority Background 4 4. Assessment Process 5 5. Model Plan Elements: Checklist 6 6. Keeper’s Summary 24 7. Keeper’s Determination 24 8. Keeper's Endorsement 25 National Records of Scotland 2 Assessment Report 1. Public Records (Scotland) Act 2011 The Public Records (Scotland) Act 2011 (the Act) received Royal assent on 20 April 2011. It is the first new public records legislation in Scotland since 1937 and came fully into force on 1 January 2013. Its primary aim is to promote efficient and accountable record keeping by named Scottish public authorities. The Act has its origins in The Historical Abuse Systemic Review: Residential Schools and Children’s Homes in Scotland 1950-1995 (The Shaw Report) published in 2007. The Shaw Report recorded how its investigations were hampered by poor record keeping and found that thousands of records had been created, but were then lost due to an inadequate legislative framework and poor records management. Crucially, it demonstrated how former residents of children’s homes were denied access to information about their formative years. The Shaw Report demonstrated that management of records in all formats (paper and electronic) is not just a bureaucratic process, but central to good governance and should not be ignored. A follow-up review of public records legislation by the Keeper of the Records of Scotland (the Keeper) found further evidence of poor records management across the public sector. -

East Renfrewshire

A Community Health and Wellbeing Profile for East Renfrewshire February 2008 Published by Glasgow Centre for Population Health Level 6 39 St Vincent Place Glasgow G1 2ER For further information please contact: Bruce Whyte, Glasgow Centre for Population Health Tel: 0141 221 9439 Email: [email protected] Web: www.gcph.co.uk/communityprofiles Contents Introduction 1 Purpose 1 Geographical coverage 2 Content 2 Notes and caveats 4 Local action to improve health and reduce inequalities 5 Evaluation 5 Acknowledgements 5 Web 6 Interpretation 6 Maps 9 Community Health Partnership Area Map 11 Greenspace Map 13 Air Quality Map 15 Trend and Spine Graphs 17 Definitions and Sources 61 A Community Health and Wellbeing Profile for East Renfrewshire Introduction This profile is one of ten new community health and wellbeing profiles that have been compiled by the Glasgow Centre for Population Health (GCPH) for the Greater Glasgow and Clyde NHS Board area. Each profile provides indicators for a range of health outcomes (e.g. life expectancy, mortality, hospitalisation) and health determinants (e.g. smoking levels, breastfeeding, income, employment, crime, education). These profiles build on the success of both the 2004 community health profiles published by NHS Health Scotland (www.scotpho.org.uk/communityprofiles), and of the ‘Let Glasgow Flourish’ report published by GCPH in April 2006 (www.gcph.co.uk/content/view/17/34/). Whilst these sources continue to be useful, there has been recognition of the need for more up-to-date health data and for information pertaining to the new Community Health (and Care) Partnership (CH(C)P) administrative structures. -

Integration Scheme Between Glasgow City Council and NHS Greater

Integration Scheme Between Glasgow City Council and NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde December 2015 Page 1 of 60 1. Introduction 1.1 The Public Bodies (Joint Working) (Scotland) Act 2014 (the Act) requires Health Boards and Local Authorities to integrate planning for, and delivery of, certain adult health and social care services. They can also choose to integrate planning and delivery of other services – additional adult health and social care services, such as Homelessness and Criminal Justice, beyond the minimum prescribed by Ministers, and children’s health and social care services. The Act requires them to prepare jointly an integration scheme setting out how this joint working is to be achieved. There is a choice of ways in which they may do this: the Health Board and Council can either delegate between each other (under s1(4(b), (c) and (d) of the Act), or can both delegate to a third body called the Integration Joint Board (under s1(4)(a) of the Act). Delegation between the Health Board and Council is commonly referred to as a “lead agency” arrangement. Delegation to an Integration Joint Board is commonly referred to as a “body corporate” arrangement. 1.2 This document sets out the integration arrangements adopted by NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde and Glasgow City Council, as required by Section 7 of the Act. This integration scheme follows the format of the model document produced by the Scottish Government, and includes all matters prescribed in Regulations. 1.3 Once the integration scheme has been approved by the Scottish Ministers, the Integration Joint Board (which has distinct legal personality) will be established by Order of the Scottish Ministers. -

For Glasgow's Greater Good

PrimaryCare Modernising Primary Care Premises and Services Through Partnership For Glasgow’s Greater Good The new Rutherglen Primary Care Centre, one of many examples of partnership working in the area ‘Greater Glasgow’s Primary Care Strategy – Shaping the Future of Primary Care – aims to revolutionise primary care services in Scotland’s largest city,’ says Ian Reid, Chief Executive, Greater Glasgow Primary Health Care NHS Trust. ‘Put together following consultation with patients, staff, community organisations, local authorities and voluntary organisations, the strategy sets out a future vision for primary care which aims to meet the needs of patients and bring the quality of health in Glasgow and surrounding area up to a level at least equal to the rest of Scotland. Around £38 million has already been invested, with a further £100 million to come over the next five years to improve and develop a wide range of services in line with national, city-wide and local priorities. These plans will only be successful if local premises and facilities are modernised to meet future needs. Funding from the Primary and Community Care Premises Modernisation Programme has made possible a number of projects in Greater Glasgow and a £48 million property plan has additionally been developed to upgrade, extend and replace a number of health centres and clinics in the city. A significant amount of work in improving premises is already underway, with improved facilities up and running in areas such as Rutherglen, Govanhill and Bridgeton. Patients have been extremely positive about the new accommodation and many staff have commented on how improvements have proven to be a genuine boost for services. -

South East Glasgow

A Community Health and Wellbeing Profile for South East Glasgow February 2008 Published by Glasgow Centre for Population Health Level 6 39 St Vincent Place Glasgow G1 2ER For further information please contact: Bruce Whyte, Glasgow Centre for Population Health Tel: 0141 221 9439 Email: [email protected] Web: www.gcph.co.uk/communityprofiles Contents Introduction 1 Purpose 1 Geographical coverage 2 Content 2 Notes and caveats 4 Local action to improve health and reduce inequalities 5 Evaluation 5 Acknowledgements 5 Web 6 Interpretation 6 Maps 9 Community Health Partnership Area Map 11 Greenspace Map 13 Air Quality Map 15 Fuel Poverty Map 17 Trend and Spine Graphs 19 Definitions and Sources 47 A Community Health and Wellbeing Profile for South East Glasgow Introduction This profile is one of ten new community health and wellbeing profiles that have been compiled by the Glasgow Centre for Population Health (GCPH) for the Greater Glasgow and Clyde NHS Board area. Each profile provides indicators for a range of health outcomes (e.g. life expectancy, mortality, hospitalisation) and health determinants (e.g. smoking levels, breastfeeding, income, employment, crime, education). These profiles build on the success of both the 2004 community health profiles published by NHS Health Scotland (www.scotpho.org.uk/communityprofiles), and of the ‘Let Glasgow Flourish’ report published by GCPH in April 2006 (www.gcph.co.uk/content/view/17/34/). Whilst these sources continue to be useful, there has been recognition of the need for more up-to-date health data and for information pertaining to the new Community Health (and Care) Partnership (CH(C)P) administrative structures. -

NHS Greater Glasgow & Clyde, Directorate of Forensic Mental

NHS Greater Glasgow & Clyde, Directorate of Forensic Mental Health and Learning Disabilities Background The Forensic Directorate provides specialist services for adults with mental health problems who may pose a risk to themselves or others, or have been in contact with the criminal justice system as a result of offending behaviour. Services are provided in a variety of settings dependent on the individuals need, this includes medium and low secure units and working with people in the community. There is strong evidence that work /employment or engaging in productive occupation can have a positive impact on an individual. This includes their mental health, quality of life and wellbeing, and it can also promote social inclusion. The Forensic Employability Pathway was developed by the Forensic Directorate for all patients within their care. It was recognised that this population was at a significant disadvantage when accessing jobs and training opportunities. Personal and social barriers as well as issues in relation to stigma, disclosure of history of offending and mental health problems could cause problems when looking to access work or engage in meaningful occupation. All patients involved in the programme are assessed by the Occupational Therapist using standardised assessments to gain an overview of the patients’ occupational functioning. This helps to identify at which stage in the employability pathway the patient is. It is also helps when looking at opportunities for skill development, vocational rehabilitation and qualification attainment appropriate to their needs. Implementation Challenges Resources and funding One challenge is the reduction in community resources. Several resources the service had previously used have now closed. -

Draft Agenda

Draft Agenda # MCQIC2018 #SPSP10 @maternitySPSP @neonatalSPSP @paediatricSPSP Title: Date: Time: Location: SPSP MCQIC Networking Event 24th October 2018 10:00 - 16:30 Hampden Park, Glasgow Theme: Building for the future Time Topic Lead 09:30 Registration and Coffee Chair: Bernie McCulloch, Improvement Advisor, MCQIC 10:00-10:10 Welcome, Introduction and Overview Joanne Matthews, Head of Improvement and Safety, Healthcare Improvement Scotland 10:10- 10:45 Delivering Quality in Rapidly Forming Graham Percival, General Manager Multidisciplinary Teams ScotSTAR, Scottish Ambulance Service 10:45 Coffee Break 11.15- 12.45 QI Session: Marie- Claire Stallard, Improvement - Quality Management Systems Advisor, TRIST - QI methodology/ engagement Alison Jones, LfE Fellow; PICU Research Project Manager, Birmingham Women’s and Children’s NHS Foundation Trust 12.45-13.00 Partnership agreements 13.00 Lunch and Networking 13.45-14.50 Breakout session : Maternity Care Clare Willocks, Clinical Lead - Obstetrics Angela Cunningham, Clinical Lead, Midwifery Cheryl Clark, Associate Improvement Advisor 13:45-14.50 Breakout session : Paediatric Care Neil Spenceley, Clinical Lead, Paediatric Care Lesley Macfarlane, Associate Improvement Advisor Alison Jones, LfE Fellow; PICU Research Project Manager, Birmingham Women’s and Children’s NHS Foundation Trust The Improvement Hub (ihub) is a part of Healthcare Improvement Scotland 13:45-14.50 Breakout session : Neonatal Care Colin Peters, Clinical Lead, Neonatal Care Dr Gopi Menon, Consultant Neonatologist, NHS Lothian