The Evolution of Ideas About Sports Through Medieval

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Myths and Legends of the Celtic Race by Thomas William Rolleston

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Myths and Legends of the Celtic Race by Thomas William Rolleston This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at http://www.gutenberg.org/license Title: Myths and Legends of the Celtic Race Author: Thomas William Rolleston Release Date: October 16, 2010 [Ebook 34081] Language: English ***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK MYTHS AND LEGENDS OF THE CELTIC RACE*** MYTHS & LEGENDS OF THE CELTIC RACE Queen Maev T. W. ROLLESTON MYTHS & LEGENDS OF THE CELTIC RACE CONSTABLE - LONDON [8] British edition published by Constable and Company Limited, London First published 1911 by George G. Harrap & Co., London [9] PREFACE The Past may be forgotten, but it never dies. The elements which in the most remote times have entered into a nation's composition endure through all its history, and help to mould that history, and to stamp the character and genius of the people. The examination, therefore, of these elements, and the recognition, as far as possible, of the part they have actually contributed to the warp and weft of a nation's life, must be a matter of no small interest and importance to those who realise that the present is the child of the past, and the future of the present; who will not regard themselves, their kinsfolk, and their fellow-citizens as mere transitory phantoms, hurrying from darkness into darkness, but who know that, in them, a vast historic stream of national life is passing from its distant and mysterious origin towards a future which is largely conditioned by all the past wanderings of that human stream, but which is also, in no small degree, what they, by their courage, their patriotism, their knowledge, and their understanding, choose to make it. -

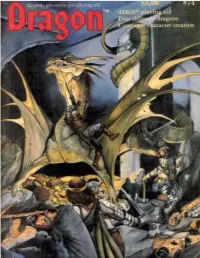

DRAGON Magazine (ISSN 0279-6848) Is Pub- the Occasion, and It Is Now So Noted

DRAGON 1 Publisher: Mike Cook Editor-in-Chid: Kim Mohan Quiet celebration Editorial staff: Marilyn Favaro Roger Raupp Birthdays dont hold as much meaning Patrick L. Price Vol. VII, No. 12 June 1983 for us any more as they did when we were Mary Kirchoff younger. That statement is true for just Office staff: Sharon Walton SPECIAL ATTRACTION about all of us, of just about any age, and Pam Maloney its true of this old magazine, too. Layout designer: Kristine L. Bartyzel June 1983 is the seventh anniversary of The DRAGON Magazine Contributing editors: Roger Moore Combat Computer . .40 Ed Greenwood the first issue of DRAGON Magazine. A playing aid that cant miss National advertising representative: In one way or another, we made a pretty Robert Dewey big thing of birthdays one through five c/o Robert LaBudde & Associates, Inc. if you have those issues, you know what I 2640 Golf Road mean. Birthday number six came and OTHER FEATURES Glenview IL 60025 Phone (312) 724-5860 went without quite as much fanfare, and Landragons . 12 now, for number seven, weve decided on Wingless wonders This issues contributing artists: a quiet celebration. (Maybe well have a Jim Holloway Phil Foglio few friends over to the cave, but thats The electrum dragon . .17 Timothy Truman Dave Trampier about it.) Roger Raupp Last of the metallic monsters? This is as good a place as any to note Seven swords . 18 DRAGON Magazine (ISSN 0279-6848) is pub- the occasion, and it is now so noted. Have Blades youll find bearable lished monthly for a subscription price of $24 per a quiet celebration of your own on our year by Dragon Publishing, a division of TSR behalf, if youve a mind to, and I hope Hobbies, Inc. -

Gabriela Pirotti Pereira Universidade Federal Do Rio Grande Do Sul, Porto Alegre, Rio Grande Do Sul, Brasil [email protected]

DOI: https://doi.org/10.18309/anp.v51i3.1456 Gabriela Pirotti Pereira Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, Rio Grande do Sul, Brasil [email protected] Abstract: Jason Colavito describes biological horror as a branch of horror fiction which deals with “uneasy feelings related to the physical body and its relationship with the natural world” (113). Those narratives often emerge during times in which there are social anxieties related to the unchecked expansion of science and the defiance of moral values is at play. In this article, I propose a reading of the tale of “Math, son of Mathonwy” which explores the possibility that this story depicts aspects of biological horror. By looking to the social and historical context of the medieval manuscript Y Mabinogi (The Mabinogi), this study goes over the scientific developments of twelfth-century Britain and correlates them to the instances of bodily transformation and physical punishment within the fourth branch of the Mabinogi. The analysis takes particular attention to the metamorphosis of the character Blodeuwedd, who is permanently altered in her physicality as judgment for her moral actions. Ultimately, the fluid nature of bodies within the tale does depict some aspects of biological horror which seem to echo some of the questions which monastic scholarly introduced during the Middle Ages. Keywords: Body Horror; Blodeuwedd; Medieval Science; Welsh Literature Resumo: Jason Colavito (2007) descreve “horror corporal” como uma seção na ficção de horror que se ocupa das “inquietações relacionadas ao corpo físico e seu relacionamento com o mundo natural” (p. 113). Tais narrativas frequentemente emergem durante períodos nos quais há ansiedades sociais conectadas à expansão científica e algum desafio aos valores morais. -

Robert Graves the White Goddess

ROBERT GRAVES THE WHITE GODDESS IN DEDICATION All saints revile her, and all sober men Ruled by the God Apollo's golden mean— In scorn of which I sailed to find her In distant regions likeliest to hold her Whom I desired above all things to know, Sister of the mirage and echo. It was a virtue not to stay, To go my headstrong and heroic way Seeking her out at the volcano's head, Among pack ice, or where the track had faded Beyond the cavern of the seven sleepers: Whose broad high brow was white as any leper's, Whose eyes were blue, with rowan-berry lips, With hair curled honey-coloured to white hips. Green sap of Spring in the young wood a-stir Will celebrate the Mountain Mother, And every song-bird shout awhile for her; But I am gifted, even in November Rawest of seasons, with so huge a sense Of her nakedly worn magnificence I forget cruelty and past betrayal, Careless of where the next bright bolt may fall. FOREWORD am grateful to Philip and Sally Graves, Christopher Hawkes, John Knittel, Valentin Iremonger, Max Mallowan, E. M. Parr, Joshua IPodro, Lynette Roberts, Martin Seymour-Smith, John Heath-Stubbs and numerous correspondents, who have supplied me with source- material for this book: and to Kenneth Gay who has helped me to arrange it. Yet since the first edition appeared in 1946, no expert in ancient Irish or Welsh has offered me the least help in refining my argument, or pointed out any of the errors which are bound to have crept into the text, or even acknowledged my letters. -

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} the Story of Queen Guinevere and Sir Lancelot

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} The Story Of Queen Guinevere And Sir Lancelot Of The Lake With Other Poems by Wilhelm Hertz The Story Of Queen Guinevere And Sir Lancelot Of The Lake: With Other Poems by Wilhelm Hertz. Access to raw data. The story of Queen Guinevere and Sir Lancelot of the lake. After the German of Wilhelm Hertz. With other poems. Abstract. Mode of access: Internet. To submit an update or takedown request for this paper, please submit an Update/Correction/Removal Request. Suggested articles. Useful links. Blog Services About CORE Contact us. Writing about CORE? Discover our research outputs and cite our work. CORE is a not-for-profit service delivered by the Open University and Jisc. Arthur, King. King Arthur was a legendary ruler of Britain whose life and deeds became the basis for a collection of tales known as the Arthurian legends. As the leading figure in British mythology, King Arthur is a national hero and a symbol of Britain's heroic heritage. But his appeal is not limited to Britain. The Arthurian story—with its elements of mystery, magic, love, war, adventure, betrayal, and fate—has touched the popular imagination and has become part of the world's shared mythology. The Celts blended stories of the warrior Arthur with those of much older mythological characters, such as Gwydion (pronounced GWID-yon), a Welsh priest-king. Old Welsh tales and poems place Arthur in traditional Celtic legends, including a hunt for an enchanted wild pig and a search for a magic cauldron, or kettle. In addition, Arthur is surrounded by a band of loyal followers who greatly resemble the disciples of Finn , the legendary Irish hero. -

Sacrificing Agency for Romance in the Chronicles of Prydain

Volume 33 Number 2 Article 8 4-15-2015 Isn't it Romantic? Sacrificing Agency for Romance in The Chronicles of Prydain Rodney M.D. Fierce Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons Recommended Citation Fierce, Rodney M.D. (2015) "Isn't it Romantic? Sacrificing Agency for Romance in The Chronicles of Prydain," Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature: Vol. 33 : No. 2 , Article 8. Available at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore/vol33/iss2/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Mythopoeic Society at SWOSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature by an authorized editor of SWOSU Digital Commons. An ADA compliant document is available upon request. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To join the Mythopoeic Society go to: http://www.mythsoc.org/join.htm Mythcon 51: A VIRTUAL “HALFLING” MYTHCON July 31 - August 1, 2021 (Saturday and Sunday) http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-51.htm Mythcon 52: The Mythic, the Fantastic, and the Alien Albuquerque, New Mexico; July 29 - August 1, 2022 http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-52.htm Abstract Addresses the vexed question of Princess Eilonwy’s gesture of giving up magic and immortality to be the wife of Taran and queen of Prydain. Was it a forced choice and a sacrifice of the capable and strong- willed girl’s agency and power, or does it proceed logically from her depiction throughout the series? Additional Keywords The Chronicles of Prydain This article is available in Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. -

Homo Monstrosus: Lloyd Alexander's Gurgi and Other Shadow Figures Of

Volume 3 Number 3 Article 9 1976 Homo Monstrosus: Lloyd Alexander’s Gurgi and Other Shadow Figures of Fantastic Literature Nancy-Lou Patterson Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons Recommended Citation Patterson, Nancy-Lou (1976) "Homo Monstrosus: Lloyd Alexander’s Gurgi and Other Shadow Figures of Fantastic Literature," Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature: Vol. 3 : No. 3 , Article 9. Available at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore/vol3/iss3/9 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Mythopoeic Society at SWOSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature by an authorized editor of SWOSU Digital Commons. An ADA compliant document is available upon request. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To join the Mythopoeic Society go to: http://www.mythsoc.org/join.htm Mythcon 51: A VIRTUAL “HALFLING” MYTHCON July 31 - August 1, 2021 (Saturday and Sunday) http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-51.htm Mythcon 52: The Mythic, the Fantastic, and the Alien Albuquerque, New Mexico; July 29 - August 1, 2022 http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-52.htm Abstract Discusses Gurgi as the shadow archetype in Alexander’s Prydain Cycle and compares him to examples in other literature. Additional Keywords Alexander, Lloyd—Jungian analysis; Alexander, Lloyd. The Prydain Cycle; Alexander, Lloyd. The Prydain Cycle—Characters—Gurgi; Shadow (Psychoanalysis); Joe R. -

The Birth of Lleu

Chapter 5 The Mabinogi of Math The Birth of Lleu The punishment of the sons of Dôn, along with the rape of Goewin itself, the stealing of the pigs, and the death of the southern hero Pryderi might collectively be seen as the initiating circumstances for the conception of Lleu Llaw Gyfess, the central hero of the Fourth Branch. To understand why this should be the case, it is necessary to re-examine the Celtic tradition relating to the ‘unusual’ birth of heroes, which we have already considered above (pp. 491-494). We will recall, in the story of Cú Chulainn there would appear to have been a number of attendent circumstances, rather than a single cause, surrounding the birth and conception of the hero. The mother of Cú Chulainn seems to have recently lost a much loved (otherworldly) foster-son, imbibed a strange drink and had a prophetic dream in which she met the god Lugh, who informed her that she was pregnant with his child. And pregnant she proved to be. The mysterious circumstances of her pregnancy led to rumours of incestuous relations with her father and considerable private shame. On her wedding night, we are told, she lay on her front and crushed the unborn child within her, yet she soon became pregnant again in the normal way with her new husband. Precisely which of these circumstances led to the birth of the hero is far from clear, but what is implied was that each of them was significant in some way to his coming. The circumstances surrounding the birth of Lleu would seem to be no less murky. -

Chapter on History of the Otherworld

PERCEPTIONS OF ANNWN: THE OTHERWORLD IN THE FOUR BRANCHES OF THE MABINOGI Rhian Rees MA Celtic Studies Dissertation Department of Welsh and Bilingual Studies Supervisor: Dr Jane Cartwright University of Wales Trinity Saint David, Lampeter 2012 2 ABSTRACT There is little description or positive information about the realm of Annwn in the Four Branches, and relatively few publications have explored the Otherworld in the Mabinogi in any depth. The redactor presumably did not deem such detail necessary since in his time the Otherworld was a place familiar to his audience from many other stories and folk-tales which have not survived to inform our own times. The objective of this thesis, therefore, is to establish the perceived location of the Celtic Otherworld, its nature and topography, and to obtain descriptions of its people, buildings and animals and any distinctive objects or characteristics pertaining to it. The ways in which Annwn influences each of the Four Branches are also considered. Some sketchy evidence is available in Welsh poetry, mostly various descriptive names reflecting different aspects of Annwn, but for more detailed information it is necessary to trawl the waters of early Irish literature. The Irish poems and stories give much fuller particulars of all characteristics of the Celtic Otherworld, though they do suggest that there was more than one such other world. Some parallels from Norse literature and the Lais of Marie de France also reinforce certain themes of this thesis, such as magical tumuli and magical bags and -

Cyfarwydd As Poet in the Fourth Branch of the Mabinogi

Cyfarwydd as Poet in the Fourth Branch of the Mabinogi The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation McKenna, Catherine. 2017. Cyfarwydd as Poet in the Fourth Branch of the Mabinogi. North American Journal of Celtic Studies 1, no. 2: 107-20. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:41687324 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Open Access Policy Articles, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#OAP Cyfarwydd as Poet in the Fourth Branch of the Mabinogi In ‘The poet as cyfarwydd in early Welsh tradition’, Patrick Ford discusses the semantic range of the term cyfarwydd and the vexed question of whether it denoted, in medieval Welsh, a storyteller. Ford contests translations of the Fourth Branch of the Mabinogi that render the term cyfarwydd, as applied to the character Gwydion, as ‘storyteller’ or ‘teller of tales’. He objects as well to the translation of cyfarwyddyd as ‘story’ or ‘tale’ (Ford 1975: 152—7). As he has described that article, I claimed that the older meaning of cyfarwyddyd in Math was 'lore; stuff of stories' and not the stories themselves.' The corollary is that the poet in early Wales was not a cyfarwydd (storyteller) but someone whose performances were informed and amplified by his acquired knowledge of such matters. (Ford 2013: 238) For Ford, the figure of Gwydion as he appears in the Fourth Branch of the Mabinogi is cyfarwydd, not because he tells stories, but because as a poet he is necessarily in possession of cyfarwyddyd, the kind of lore that was an essential component of the ‘stuff’ of poetry, as well as of stories. -

The Fourth Branch of the Mabinogi: Structural Analysis Illuminates Character Motivation

Volume 19 Number 4 Article 6 Fall 10-15-1993 The Fourth Branch of the Mabinogi: Structural Analysis Illuminates Character Motivation Corinne Larsen Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons Recommended Citation Larsen, Corinne (1993) "The Fourth Branch of the Mabinogi: Structural Analysis Illuminates Character Motivation," Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature: Vol. 19 : No. 4 , Article 6. Available at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore/vol19/iss4/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Mythopoeic Society at SWOSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature by an authorized editor of SWOSU Digital Commons. An ADA compliant document is available upon request. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To join the Mythopoeic Society go to: http://www.mythsoc.org/join.htm Mythcon 51: A VIRTUAL “HALFLING” MYTHCON July 31 - August 1, 2021 (Saturday and Sunday) http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-51.htm Mythcon 52: The Mythic, the Fantastic, and the Alien Albuquerque, New Mexico; July 29 - August 1, 2022 http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-52.htm Abstract Uses structural analysis (from Levi-Strauss) of the Fourth Branch (the story of Lleu and Gwydion) to discover information about character motivations. Attempts to answer the apparent riddle of why Lleu sets up his own death. Additional Keywords The Mabinogion; Structural analysis (method of Claude Levi-Strauss) This article is available in Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. -

Welsh Writing and Postcoloniality: the Strategic Use of the Blodeuwedd Myth in Emyr Humphreys’S Novels Diane Green Contents

ISSN 0214-4808 ● CODEN RAEIEX Editor Emeritus Pedro Jesús Marcos Pérez Editors José Mateo Martínez Francisco Yus Editorial Board Asunción Alba (UNED) ● Román Álvarez (University of Salamanca) ● Norman F. Blake (University of Sheffi eld) ● Juan de la Cruz (University of Málaga) ● Bernd Dietz (University of La Laguna) ● Angela Downing (University of Madrid, Compluten se) ● Francisco Fernández (University of Valen cia) ● Fernando Galván (University of Alcalá) ● Francisco García Tortosa (University of Seville) ● Pedro Guardia (University of Barcelona) ● Ernst-August Gutt (SIL) ● Pilar Hidalgo (Univer sity of Málaga) ● Ramón López Ortega (University of Extremadura) ● Doireann MacDermott (Universi ty of Barcelona) ● Catalina Montes (Uni- versity of Salamanca) ● Susana Onega (University of Zaragoza) ● Esteban Pujals (Uni ver sity of Madrid, Complutense) ● Julio C. Santoyo (University of León) ● John Sinclair (Uni versity of Birmingham) Advisory Board Enrique Alcaraz Varó (University of Alicante) ● Manuel Almagro Jiménez (University of Seville) ● José Antonio Álvarez Amorós (University of La Coruña) ● Antonio Bravo García (University of Oviedo) ● Miguel Ángel Campos Pardillos (University of Alicante) ● Silvia Caporale (University of Alicante) ● José Carnero González (Universi ty of Seville) ● Fernando Cerezal (University of Alcalá) ● Ángeles de la Concha (UNED) ● Isabel Díaz Sánchez (University of Alicante) ● Teresa Gibert Maceda (UNED) ● Teresa Gómez Reus (University of Alicante) ● José S. Gómez Soliño (Universi ty of La Laguna) ● José Manuel González (University of Alicante) ● Brian Hughes (University of Alicante) ● Antonio Lillo (University of Alicante) ● José Mateo Martínez (University of Alicante) ● Cynthia Miguélez Giambruno (University of Alicante) ● Bryn Moody (University of Alicante) ● Ana Isabel Ojea López (University of Oviedo) ● Félix Rodríguez González (Universi ty of Alicante) ● María Socorro Suárez (University of Oviedo) ● Justine Tally (University of La Laguna) ● Francisco Javier Torres Ribelles (University of Alicante) ● M.