Homo Monstrosus: Lloyd Alexander's Gurgi and Other Shadow Figures Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Embeddings for KB and Text Representation, Extraction and Question Answering

Embeddings for multi-relational data Pros and cons of embedding models Embeddings for KB and text representation, extraction and question answering. Jason Westony & Antoine Bordes & Sumit Chopra Facebook AI Research External Collaborators: Alberto Garcia-Duran & Nicolas Usunier & Oksana Yakhnenko y Some of this work was done while J. Weston worked at Google. 1 / 24 Embeddings for multi-relational data Pros and cons of embedding models Multi-relational data Data is structured as a graph Each node = an entity Each edge=a relation/fact A relation = (sub, rel, obj): sub =subject, rel = relation type, obj = object. Nodes w/o features. We want to also link this to text!! 2 / 24 Embeddings for multi-relational data Pros and cons of embedding models Embedding Models KBs are hard to manipulate Large dimensions: 105=108 entities, 104=106 rel. types Sparse: few valid links Noisy/incomplete: missing/wrong relations/entities Two main components: 1 Learn low-dimensional vectors for words and KB entities and relations. 2 Stochastic gradient based training, directly trained to define a similarity criterion of interest. 3 / 24 Embeddings for multi-relational data Pros and cons of embedding models Link Prediction Add new facts without requiring extra knowledge From known information, assess the validity of an unknown fact Goal: We want to model, from data, P[relk (subi ; objj ) = 1] ! collective classification ! towards reasoning in embedding spaces 4 / 24 Embeddings for multi-relational data Pros and cons of embedding models Previous Work Tensor factorization -

Actions Héroïques

Shadows over Camelot FAQ 1.0 Oct 12, 2005 The following FAQ lists some of the most frequently asked questions surrounding the Shadows over Camelot boardgame. This list will be revised and expanded by the Authors as required. Many of the points below are simply a repetition of some easily overlooked rules, while a few others offer clarifications or provide a definitive interpretation of rules. For your convenience, they have been regrouped and classified by general subject. I. The Heroic Actions A Knight may only do multiple actions during his turn if each of these actions is of a DIFFERENT nature. For memory, the 5 possible action types are: A. Moving to a new place B. Performing a Quest-specific action C. Playing a Special White card D. Healing yourself E. Accusing another Knight of being the Traitor. Example: It is Sir Tristan's turn, and he is on the Black Knight Quest. He plays the last Fight card required to end the Quest (action of type B). He thus automatically returns to Camelot at no cost. This move does not count as an action, since it was automatically triggered by the completion of the Quest. Once in Camelot, Tristan will neither be able to draw White cards nor fight the Siege Engines, if he chooses to perform a second Heroic Action. This is because this would be a second Quest-specific (Action of type B) action! On the other hand, he could immediately move to another new Quest (because he hasn't chosen a Move action (Action of type A.) yet. -

The Fates of the Princes of Dyfed Cenydd Morus (Kenneth Morris) Illustrations by Reginald Machell

Theosophical University Press Online Edition The Fates of the Princes of Dyfed Cenydd Morus (Kenneth Morris) Illustrations by Reginald Machell Copyright © 1914 by Katherine Tingley; originally published at Point Loma, California. Electronic edition 2000 by Theosophical University Press ISBN 1- 55700-157-x. This edition may be downloaded for off-line viewing without charge. For ease of searching, no diacritical marks appear in the electronic version of the text. To Katherine Tingley: Leader and Official Head of the Universal Brotherhood and Theosophical Society, whose whole life has been devoted to the cause of Peace and Universal Brotherhood, this book is respectfully dedicated Contents Preface The Three Branches of the Bringing-in of it, namely: The Sovereignty of Annwn I. The Council of the Immortals II. The Hunt in Glyn Cuch III. The Slaying of Hafgan The Story of Pwyll and Rhianon, or The Book of the Three Trials The First Branch of it, called: The Coming of Rhianon Ren Ferch Hefeydd I. The Making-known of Gorsedd Arberth, and the Wonderful Riding of Rhianon II. The First of the Wedding-Feasts at the Court of Hefeydd, and the Coming of Gwawl ab Clud The Second Branch of it, namely: The Basket of Gwaeddfyd Newynog, and Gwaeddfyd Newynog Himself I. The Anger of Pendaran Dyfed, and the Putting of Firing in the Basket II. The Over-Eagerness of Ceredig Cwmteifi after Knowledge, and the Putting of Bulrush-Heads in the Basket III. The Circumspection of Pwyll Pen Annwn, and the Filling of the Basket at Last The First Branch of it again: III. -

Arawn Celtic God of the Otherworld

Samhain ~ Full Moon in Scorpio 12th May 2017 On this night we will be connecting to the energy of the Scorpio Full Moon under the guidance of the God Arawn Celtic God of the Otherworld. This is the time of the year when the boundary is thinnest between the worlds of the living and the dead. The powers of divination, the Sight, and supernatural communication are stronger over this period and it is considered a potent time to communicate with those that inhabit the Other Worlds. Sydney Ritual Introduction Scorpio Full Moon: Scorpio energy is all about transformation and reaching higher levels of consciousness. In fact, Scorpio energy has the potential to reach Divine levels of consciousness, but at the same time, it also has the ability to reach extremely low levels of consciousness as well. No matter where you fall on the “consciousness spectrum” it is likely that this Full Moon is going to leave a lasting impact. It is also likely that this Full Moon is going to help open your consciousness to a new level so you can see things in a different light. Things may feel a little uneasy as changes may be in the air, but the best way to manage this energy moving forward is remembering your personal power. Very often we forget that we have a strength and power within us. This power gives us the ability to step up and take responsibility over our lives no matter what troubles woe find ourselves in. The minute we give away our power, it becomes very difficult to deal with the situations that life throws our way. -

Winning ""Chronicles of Prydain""1 Is Now a Thret'-Dimt-Nsioniil Qpwnated Adventure ^Aute

The Walt Disney^ inductions movie, based on novelist Mayd Alexander's Newbery A ward- winning ""Chronicles of Prydain""1 is now a thret'-dimt-nsioniil qpwnated adventure ^aute... Lloyd Alexander blends the rich elements of Welsh legend and universal mythology in his five-volume fantasy epic "The Chronicles of Prydain." "...considered to be the most significant fantasy cycle created for children today by an American author." — from the citation to The High King for the Newbery Medal given annually by the American Library Association for "the most distinguished contribution to American literature for children." The Chronicles of Prydain by Lloyd Alexander; The Book of Three The Black Cauldron The Castle of Llyr Taran Wanderer The High King Other Prydain books by Lloyd Alexander: The Foundling, and Other Tales of Prydain Coll and His White Pig The Truthful Harp Portions of ihis manual arc condensed or excerpted from: The Book of Three, © 1964 by Lloyd Alexander The High King. '£.• 1%8 by Lloyd Alexander The Foundling, and Other Talcs of Prydain. © 1973 by Lloyd Alexander The Black Cauldron, an all-animated feature, ict Wall Disney Productions MCMLXXXV DALLBEN AND THE BOOK OF THREE hen he was just a baby, Dallben, greatest of enchanters in all Prydain, was abandoned in a wicker basket at the edge of the Marshes of Morva. There he was found by three witches, Orddu, Orwen and Orgoch, and was taken to live with them in their home at the center of the marsh. m As he grew, Dallben watched the witches in all they did, and learned their powers of enchantment. -

Arthurian Legend

Nugent: English 11 Fall What do you know about King Arthur, Camelot and the Knights of the Round Table? Do you know about any Knights? If so, who? If you know anything about King Arthur, why did you learn about King Arthur? If you don’t know anything, what can you guess King Arthur, Camelot, or Knights. A LEGEND is a story told about extraordinary deeds that has been told and retold for generations among a group of people. Legends are thought to have a historical basis, but may also contain elements of magic and myth. MYTH: a story that a particular culture believes to be true, using the supernatural to interpret natural events & to explain the nature of the universe and humanity. An ARCHETYPE is a reoccurring character type, setting, or action that is recognizable across literature and cultures that elicits a certain feeling or reaction from the reader. GOOD EVIL • The Hero • Doppelganger • The Mother The Sage • The Monster • The Scapegoat or sacrificial • The Trickster lamb • Outlaw/destroyer • The Star-crossed lovers • The Rebel • The Orphan • The Tyrant • The Fool • The Hag/Witch/Shaman • The Sadist A ROMANCE is an imaginative story concerned with noble heroes, chivalric codes of honor, passionate love, daring deeds, & supernatural events. Writers of romances tend to idealize their heroes as well as the eras in which the heroes live. Romances typically include these MOTIFS: adventure, quests, wicked adversaries, & magic. Motif: an idea, object, place, or statement that appears frequently throughout a piece of writing, which helps contribute to the work’s overall theme 1. -

Sir Gawain and the Green Knight

A TEACHER’S GUIDE TO THE SIGNET CLASSICS EDITION OF SIR GAWAIN AND THE GREEN KNIGHT BY KELLI McCALL SELF TEACHER’S GUIDE TEACHER’S DR Gawain TG 100912a.indd 1 10/24/12 4:55 PM 2 A Teacher’s Guide to Sir Gawain and the Green Knight TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................3 LIST OF CHARACTERS .............................................................................................................3 SYNOPSIS OF THE POEM .......................................................................................................4 PREREADING ACTIVITIES .......................................................................................................6 I. BUILDING BACKGROUND KNOWLEDGE IN HISTORY AND LITERATURE ................................................................................6 II. BUILDING BACKGROUND KNOWLEDGE THROUGH INITIAL EXPLORATION OF THEMES ............................................10 DURING READING ACTIVITIES..........................................................................................13 I. DISCUSSION QUESTIONS ..................................................................................13 II. ACTIVITIES TO GENERATE RESPONSE AND EXPLORATION OF THE TEXT ......................................................................15 AFTER READING ACTIVITIES .............................................................................................16 I. TEXTBASED TOPICS FOR ESSAYS AND DISCUSSIONS ..........................16 -

Year 8 Term 1 (Weeks 1-12) Subject Week 1 Week 2 Week 3 Week 4 Week 5 Week 6 Week 7 Week 8 Week 9 Week 10 Week 11 Week 12

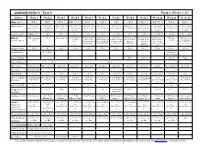

AmblesideOnline's - Year 8 Term 1 (Weeks 1-12) Subject Week 1 Week 2 Week 3 Week 4 Week 5 Week 6 Week 7 Week 8 Week 9 Week 10 Week 11 Week 12 Bible New T Matt 1 Matt 2 Matt 3, 4 Matt 4:18-5:16 Matt 5:17-48 Matt 6 Matt 7 Matt 8 Matt 9:1-17 Matt 9:18-38 Matt 10 Matt 11 Old testament Jud 1-3; Ps Jud 4-6; Ps Jud 7-9:21; Ps Jud 9:22-11; Ps Jud 12-15; Ps Jud 16-18; Ps Jud 19-21; Ps Ruth; Ps 112, 1Sam 1-3; Ps 1Sam 4-8; Ps 1Sam 9-12; Ps 1Sam 13, 14; Ps 106:1-23; Pr 1:1- 106:24-48; Pr 107:1-22; Pr 2:1- 107:23-43; Pr 108; Pr 3:1-20 109; Pr 3:21-35 110, 111; Pr 4:1- 113; Pr 4:14-27 114, 115; Pr 5:1- 116, 117; Pr 118:1-18; Pr 6:1- 118:19-29; Pr 19 1:20-33 9 2:10-22 3 14 5:15-23 19 6:20-35 Case for Christ Intro, Ch 1 Ch 2 Ch 3 Ch 4 Ch 5 Ch 6 Ch 7&8 Ch 9 Ch 10 Ch 11&12 Ch 13 Ch 14 - end History Ch 1 Columbus, Ch 2 Ch 3 Henry VIII ch 4 to page 49, end of ch 4 and first second half of ch 5 from "In the first half of ch 7 to second half of ch 7 second half of ch 8 Ch 9 Drake, Ch 10 1588, Sir Luther "On October 9, half of ch 5 to and beginning of ch Autumn, when the page 97, "Catholic to middle of ch 8 from "meanwhile, Armada Walter Raleigh, The New World 1529. -

CELTIC MYTHOLOGY Ii

i CELTIC MYTHOLOGY ii OTHER TITLES BY PHILIP FREEMAN The World of Saint Patrick iii ✦ CELTIC MYTHOLOGY Tales of Gods, Goddesses, and Heroes PHILIP FREEMAN 1 iv 1 Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries. Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America. © Philip Freeman 2017 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above. You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer. CIP data is on file at the Library of Congress ISBN 978–0–19–046047–1 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Printed by Sheridan Books, Inc., United States of America v CONTENTS Introduction: Who Were the Celts? ix Pronunciation Guide xvii 1. The Earliest Celtic Gods 1 2. The Book of Invasions 14 3. The Wooing of Étaín 29 4. Cú Chulainn and the Táin Bó Cuailnge 46 The Discovery of the Táin 47 The Conception of Conchobar 48 The Curse of Macha 50 The Exile of the Sons of Uisliu 52 The Birth of Cú Chulainn 57 The Boyhood Deeds of Cú Chulainn 61 The Wooing of Emer 71 The Death of Aife’s Only Son 75 The Táin Begins 77 Single Combat 82 Cú Chulainn and Ferdia 86 The Final Battle 89 vi vi | Contents 5. -

The Book of Three by Lloyd Alexander

Teacher Guide The Book of Three by Lloyd Alexander Questions for Socratic Discussion by Melanie Huff © 2012, The Center for Literary Education 3350 Beck Road Rice, WA 99167 (509) 738-2837 www.centerforlit.com Contents Introduction 2 Questions about Structure: Setting 4 Questions about Structure: Characters 6 Questions about Structure: Conflict and Plot 11 Questions about Structure: Theme 14 Questions about Style 16 Questions about Context 18 Suggested Essay Assignments 19 Story Charts 20 Introduction This teacher guide is intended to assist the teacher or parent in conducting meaningful discussions of literature in the classroom or home school. Questions and answers follow the pattern presented in Teaching the Classics, the Center for Literary Education’s two day literature seminar. Though the concepts underlying this approach to literary analysis are explained in detail in that seminar, the following brief summary presents the basic principles upon which this guide is based. The Teaching the Classics approach to literary analysis and interpretation is built around three unique ideas which, when combined, produce a powerful instrument for understanding and teaching literature: First: All works of fiction share the same basic elements — Context, Structure, and Style. A literature lesson that helps the student identify these elements in a story prepares him for meaningful discussion of the story’s themes. Context encompasses all of the details of time and place surrounding the writing of a story, including the personal life of the author as well as historical events that shaped the author’s world. Structure includes the essential building blocks that make up a story, and that all stories have in common: Conflict, Plot (which includes exposition, rising action, climax, denouement, and conclusion), Setting, Characters and Theme. -

Lloyd Alexander's the Book of Three

Lloyd Alexander’s The Book of Three: A Discussion Guide By David Bruce SMASHWORDS EDITION Copyright 2008 by Bruce D. Bruce Thank you for downloading this free ebook. You are welcome to share it with your friends. This book may be reproduced, copied and distributed for non-commercial purposes, provided the book remains in its complete original form. If you enjoyed this book, please return to Smashwords.com to discover other works by this author. Thank you for your support. Dedicated with Love to Caleb Bruce ••• Preface The purpose of this book is educational. I enjoy reading Lloyd Alexander’s The Book of Three, and I believe that it is an excellent book for children (and for adults such as myself) to read. This book contains many questions about Lloyd Alexander’s The Book of Three and their answers. I hope that teachers of children will find it useful as a guide for discussions. It can also be used for short writing assignments. Students can answer selected questions from this little guide orally or in one or more paragraphs. I hope to encourage teachers to teach Lloyd Alexander’s The Book of Three, and I hope to lessen the time needed for teachers to prepare to teach this book. This book uses many short quotations from Lloyd Alexander’s The Book of Three. This use is consistent with fair use: § 107. Limitations on exclusive rights: Fair use Release date: 2004-04-30 Notwithstanding the provisions of sections 106 and 106A, the fair use of a copyrighted work, including such use by reproduction in copies or phonorecords or by any other means specified by that section, for purposes such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching (including multiple copies for classroom use), scholarship, or research, is not an infringement of copyright. -

Myths and Legends of the Celtic Race by Thomas William Rolleston

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Myths and Legends of the Celtic Race by Thomas William Rolleston This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at http://www.gutenberg.org/license Title: Myths and Legends of the Celtic Race Author: Thomas William Rolleston Release Date: October 16, 2010 [Ebook 34081] Language: English ***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK MYTHS AND LEGENDS OF THE CELTIC RACE*** MYTHS & LEGENDS OF THE CELTIC RACE Queen Maev T. W. ROLLESTON MYTHS & LEGENDS OF THE CELTIC RACE CONSTABLE - LONDON [8] British edition published by Constable and Company Limited, London First published 1911 by George G. Harrap & Co., London [9] PREFACE The Past may be forgotten, but it never dies. The elements which in the most remote times have entered into a nation's composition endure through all its history, and help to mould that history, and to stamp the character and genius of the people. The examination, therefore, of these elements, and the recognition, as far as possible, of the part they have actually contributed to the warp and weft of a nation's life, must be a matter of no small interest and importance to those who realise that the present is the child of the past, and the future of the present; who will not regard themselves, their kinsfolk, and their fellow-citizens as mere transitory phantoms, hurrying from darkness into darkness, but who know that, in them, a vast historic stream of national life is passing from its distant and mysterious origin towards a future which is largely conditioned by all the past wanderings of that human stream, but which is also, in no small degree, what they, by their courage, their patriotism, their knowledge, and their understanding, choose to make it.