The Book of Three by Lloyd Alexander

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Book of Three Free Ebook

FREETHE BOOK OF THREE EBOOK Lloyd Alexander | 190 pages | 16 May 2006 | Henry Holt & Company | 9780805080483 | English | New York, NY, United States “The Book of Three” at Usborne Children’s Books Taran is desperate The Book of Three adventure. Being a lowly Assistant Pig-Keeper just isn't exciting. That is, until the magical pig, Hen Wen, disappears and Taran embarks on a death-defying quest to save her from the evil Horned King. His perilous adventures bring Taran many new friends: an irritable dwarf, an impulsive bard, a strange hairy beast and the hot-headed Princess Eilonwy. Together, they face many dangers, from the deathless Cauldron-Born warriors, dragons, witches and the terrifying Horned King himself. Taran learns much about his identity, but the mysterious Book of Three is yet to reveal his true destiny. He was reading by the time he was 3, and though he did poorly in school, at the age of fifteen, he announced that he wanted to become a writer. Alexander served in the Intelligence Department, stationed in Wales, and then went on to Counter-Intelligence in Paris, where he was promoted to Staff Sergeant. When the war ended in '45, Alexander applied to the Sorbonne, but returned to the States in '46, now married. Alexander worked as an unpublished The Book of Three for seven years, accepting positions such as cartoonist, advertising copywriter, layout artist, and The Book of Three editor for a small magazine. Directly after the war, he had translated works for such artists as Jean Paul Sartre. In"And Let the Credit Go" was published, The Book of Three first book which led to 10 years of writing for an adult audience. -

Not Another Trash Tournament Written by Eliza Grames, Melanie Keating, Virginia Ruiz, Joe Nutter, and Rhea Nelson

Not Another Trash Tournament Written by Eliza Grames, Melanie Keating, Virginia Ruiz, Joe Nutter, and Rhea Nelson PACKET ONE 1. This character’s coach says that although it “takes all kinds to build a freeway” he is not equipped for this character’s kind of weirdness close the playoffs. This character lost his virginity to the homecoming queen and the prom queen at the same time and says he’ll be(*) “scoring more than baskets” at an away game and ends up in a teacher’s room wearing a thong which inspires the entire basketball team to start wearing them at practice. When Carrie brags about dating this character, Heather, played by Ashanti, hits her in the back of the head with a volleyball before Brittany Snow’s character breaks up the fight. Four girls team up to get back at this high school basketball star for dating all of them at once. For 10 points, name this character who “must die.” ANSWER: John Tucker [accept either] 2. The hosts of this series that premiered in 2003 once crafted a combat robot named Blendo, and one of those men served as a guest judge on the 2016 season of BattleBots. After accidentally shooting a penny into a fluorescent light on one episode of this show, its cast had to be evacuated due to mercury vapor. On a “Viewers’ Special” episode of this show, its hosts(*) attempted to sneeze with their eyes open, before firing cigarette butts from a rifle. This show’s hosts produced the short-lived series Unchained Reaction, which also aired on the Discovery Channel. -

Embeddings for KB and Text Representation, Extraction and Question Answering

Embeddings for multi-relational data Pros and cons of embedding models Embeddings for KB and text representation, extraction and question answering. Jason Westony & Antoine Bordes & Sumit Chopra Facebook AI Research External Collaborators: Alberto Garcia-Duran & Nicolas Usunier & Oksana Yakhnenko y Some of this work was done while J. Weston worked at Google. 1 / 24 Embeddings for multi-relational data Pros and cons of embedding models Multi-relational data Data is structured as a graph Each node = an entity Each edge=a relation/fact A relation = (sub, rel, obj): sub =subject, rel = relation type, obj = object. Nodes w/o features. We want to also link this to text!! 2 / 24 Embeddings for multi-relational data Pros and cons of embedding models Embedding Models KBs are hard to manipulate Large dimensions: 105=108 entities, 104=106 rel. types Sparse: few valid links Noisy/incomplete: missing/wrong relations/entities Two main components: 1 Learn low-dimensional vectors for words and KB entities and relations. 2 Stochastic gradient based training, directly trained to define a similarity criterion of interest. 3 / 24 Embeddings for multi-relational data Pros and cons of embedding models Link Prediction Add new facts without requiring extra knowledge From known information, assess the validity of an unknown fact Goal: We want to model, from data, P[relk (subi ; objj ) = 1] ! collective classification ! towards reasoning in embedding spaces 4 / 24 Embeddings for multi-relational data Pros and cons of embedding models Previous Work Tensor factorization -

Blackcauldron-Manual

- Lloyd Alexander blends the rich elements of Welsh legend and universal mythology in his five-volume fantasy epic "The Chronicles of Prydain." . " ... considered to be the most significant fantasy cycle created for children today by an American author." -- from the citation to The High King for the Newbery Medal given annually by the American Library Association for " the most distinguished contribution to American literature for children. " The Chronicles of Prydain by Lloyd Alexander: The Book of Three The Black Cauldron The Castle of Llyr Taran Wanderer The High King Other Prydain books by Lloyd Alexander: The Foundling, and Other Tales of Prydain Coll and His White Pig The Truthful Harp Portions of this manual are condensed or exc~rpted from: The Book of Three, © 1964 by Lloyd Alexander The High King , © 1968 by Lloyd Alexander The Foundling, and Other Tales of Prydain, © 1973 by Lloyd Alexander The Black Cauldron, an all-animated feature, © Walt Disney Productions MCMLXXXV DALLBEN AND THE BOOK OF THREE hen he was just a baby, Dallben, greatest of enchanters in all Prydai n , was abandoned in a wicker basket at the edge of the Marshes of Morva. There he was found by three witches, Orddu, Orwen and Orgoch, and was taken to live with them in their home at the center of the marsh. As he grew, Dallben watched the witches in all they did, and learned their powers of enchantment. On the day he left them to make a life for himself, they made him a present of an ancient volume entitled The Book of Three. -

Winning ""Chronicles of Prydain""1 Is Now a Thret'-Dimt-Nsioniil Qpwnated Adventure ^Aute

The Walt Disney^ inductions movie, based on novelist Mayd Alexander's Newbery A ward- winning ""Chronicles of Prydain""1 is now a thret'-dimt-nsioniil qpwnated adventure ^aute... Lloyd Alexander blends the rich elements of Welsh legend and universal mythology in his five-volume fantasy epic "The Chronicles of Prydain." "...considered to be the most significant fantasy cycle created for children today by an American author." — from the citation to The High King for the Newbery Medal given annually by the American Library Association for "the most distinguished contribution to American literature for children." The Chronicles of Prydain by Lloyd Alexander; The Book of Three The Black Cauldron The Castle of Llyr Taran Wanderer The High King Other Prydain books by Lloyd Alexander: The Foundling, and Other Tales of Prydain Coll and His White Pig The Truthful Harp Portions of ihis manual arc condensed or excerpted from: The Book of Three, © 1964 by Lloyd Alexander The High King. '£.• 1%8 by Lloyd Alexander The Foundling, and Other Talcs of Prydain. © 1973 by Lloyd Alexander The Black Cauldron, an all-animated feature, ict Wall Disney Productions MCMLXXXV DALLBEN AND THE BOOK OF THREE hen he was just a baby, Dallben, greatest of enchanters in all Prydain, was abandoned in a wicker basket at the edge of the Marshes of Morva. There he was found by three witches, Orddu, Orwen and Orgoch, and was taken to live with them in their home at the center of the marsh. m As he grew, Dallben watched the witches in all they did, and learned their powers of enchantment. -

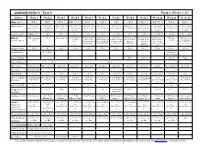

Year 8 Term 1 (Weeks 1-12) Subject Week 1 Week 2 Week 3 Week 4 Week 5 Week 6 Week 7 Week 8 Week 9 Week 10 Week 11 Week 12

AmblesideOnline's - Year 8 Term 1 (Weeks 1-12) Subject Week 1 Week 2 Week 3 Week 4 Week 5 Week 6 Week 7 Week 8 Week 9 Week 10 Week 11 Week 12 Bible New T Matt 1 Matt 2 Matt 3, 4 Matt 4:18-5:16 Matt 5:17-48 Matt 6 Matt 7 Matt 8 Matt 9:1-17 Matt 9:18-38 Matt 10 Matt 11 Old testament Jud 1-3; Ps Jud 4-6; Ps Jud 7-9:21; Ps Jud 9:22-11; Ps Jud 12-15; Ps Jud 16-18; Ps Jud 19-21; Ps Ruth; Ps 112, 1Sam 1-3; Ps 1Sam 4-8; Ps 1Sam 9-12; Ps 1Sam 13, 14; Ps 106:1-23; Pr 1:1- 106:24-48; Pr 107:1-22; Pr 2:1- 107:23-43; Pr 108; Pr 3:1-20 109; Pr 3:21-35 110, 111; Pr 4:1- 113; Pr 4:14-27 114, 115; Pr 5:1- 116, 117; Pr 118:1-18; Pr 6:1- 118:19-29; Pr 19 1:20-33 9 2:10-22 3 14 5:15-23 19 6:20-35 Case for Christ Intro, Ch 1 Ch 2 Ch 3 Ch 4 Ch 5 Ch 6 Ch 7&8 Ch 9 Ch 10 Ch 11&12 Ch 13 Ch 14 - end History Ch 1 Columbus, Ch 2 Ch 3 Henry VIII ch 4 to page 49, end of ch 4 and first second half of ch 5 from "In the first half of ch 7 to second half of ch 7 second half of ch 8 Ch 9 Drake, Ch 10 1588, Sir Luther "On October 9, half of ch 5 to and beginning of ch Autumn, when the page 97, "Catholic to middle of ch 8 from "meanwhile, Armada Walter Raleigh, The New World 1529. -

Lloyd Alexander's the Book of Three

Lloyd Alexander’s The Book of Three: A Discussion Guide By David Bruce SMASHWORDS EDITION Copyright 2008 by Bruce D. Bruce Thank you for downloading this free ebook. You are welcome to share it with your friends. This book may be reproduced, copied and distributed for non-commercial purposes, provided the book remains in its complete original form. If you enjoyed this book, please return to Smashwords.com to discover other works by this author. Thank you for your support. Dedicated with Love to Caleb Bruce ••• Preface The purpose of this book is educational. I enjoy reading Lloyd Alexander’s The Book of Three, and I believe that it is an excellent book for children (and for adults such as myself) to read. This book contains many questions about Lloyd Alexander’s The Book of Three and their answers. I hope that teachers of children will find it useful as a guide for discussions. It can also be used for short writing assignments. Students can answer selected questions from this little guide orally or in one or more paragraphs. I hope to encourage teachers to teach Lloyd Alexander’s The Book of Three, and I hope to lessen the time needed for teachers to prepare to teach this book. This book uses many short quotations from Lloyd Alexander’s The Book of Three. This use is consistent with fair use: § 107. Limitations on exclusive rights: Fair use Release date: 2004-04-30 Notwithstanding the provisions of sections 106 and 106A, the fair use of a copyrighted work, including such use by reproduction in copies or phonorecords or by any other means specified by that section, for purposes such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching (including multiple copies for classroom use), scholarship, or research, is not an infringement of copyright. -

2004 World Fantasy Awards Information Each Year the Convention Members Nominate Two of the Entries for Each Category on the Awards Ballot

2004 World Fantasy Awards Information Each year the convention members nominate two of the entries for each category on the awards ballot. To this, the judges can add three or more nominees. No indication of the nominee source appears on the final ballot. The judges are chosen by the World Fantasy Awards Administration. Winners will be announced at the 2004 World Fantasy Convention Banquet on Sunday October 31, 2004, at the Tempe Mission Palms Hotel in Tempe, Arizona, USA. Eligibility: All nominated material must have been published in 2003 or have a 2003 cover date. Only living persons may be nominated. When listing stories or other material that may not be familiar to all the judges, please include pertinent information such as author, editor, publisher, magazine name and date, etc. Nominations: You may nominate up to five items in each category, in no particular order. You don't have to nominate items in every category but you must nominate in more than one. The items are not point-rated. The two items receiving the most nominations (except for those ineligible) will be placed on the final ballot. The remainder are added by the judges. The winners are announced at the World Fantasy Convention Banquet. Categories: Life Achievement; Best Novel; Best Novella; Best Short Story; Best Anthology; Best Collection; Best Artist; Special Award Professional; Special Award Non-Professional. A list of past award winners may be found at http://www.worldfantasy.org/awards/awardslist.html Life Achievement: At previous conventions, awards have been presented to: Forrest J. Ackerman, Lloyd Alexander, Everett F. -

Sacrificing Agency for Romance in the Chronicles of Prydain

Volume 33 Number 2 Article 8 4-15-2015 Isn't it Romantic? Sacrificing Agency for Romance in The Chronicles of Prydain Rodney M.D. Fierce Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons Recommended Citation Fierce, Rodney M.D. (2015) "Isn't it Romantic? Sacrificing Agency for Romance in The Chronicles of Prydain," Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature: Vol. 33 : No. 2 , Article 8. Available at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore/vol33/iss2/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Mythopoeic Society at SWOSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature by an authorized editor of SWOSU Digital Commons. An ADA compliant document is available upon request. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To join the Mythopoeic Society go to: http://www.mythsoc.org/join.htm Mythcon 51: A VIRTUAL “HALFLING” MYTHCON July 31 - August 1, 2021 (Saturday and Sunday) http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-51.htm Mythcon 52: The Mythic, the Fantastic, and the Alien Albuquerque, New Mexico; July 29 - August 1, 2022 http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-52.htm Abstract Addresses the vexed question of Princess Eilonwy’s gesture of giving up magic and immortality to be the wife of Taran and queen of Prydain. Was it a forced choice and a sacrifice of the capable and strong- willed girl’s agency and power, or does it proceed logically from her depiction throughout the series? Additional Keywords The Chronicles of Prydain This article is available in Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. -

Homo Monstrosus: Lloyd Alexander's Gurgi and Other Shadow Figures Of

Volume 3 Number 3 Article 9 1976 Homo Monstrosus: Lloyd Alexander’s Gurgi and Other Shadow Figures of Fantastic Literature Nancy-Lou Patterson Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons Recommended Citation Patterson, Nancy-Lou (1976) "Homo Monstrosus: Lloyd Alexander’s Gurgi and Other Shadow Figures of Fantastic Literature," Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature: Vol. 3 : No. 3 , Article 9. Available at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore/vol3/iss3/9 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Mythopoeic Society at SWOSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature by an authorized editor of SWOSU Digital Commons. An ADA compliant document is available upon request. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To join the Mythopoeic Society go to: http://www.mythsoc.org/join.htm Mythcon 51: A VIRTUAL “HALFLING” MYTHCON July 31 - August 1, 2021 (Saturday and Sunday) http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-51.htm Mythcon 52: The Mythic, the Fantastic, and the Alien Albuquerque, New Mexico; July 29 - August 1, 2022 http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-52.htm Abstract Discusses Gurgi as the shadow archetype in Alexander’s Prydain Cycle and compares him to examples in other literature. Additional Keywords Alexander, Lloyd—Jungian analysis; Alexander, Lloyd. The Prydain Cycle; Alexander, Lloyd. The Prydain Cycle—Characters—Gurgi; Shadow (Psychoanalysis); Joe R. -

The Project Gutenberg Ebook of Y Gododin, by Aneurin Copyright

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Y Gododin, by Aneurin Copyright laws are changing all over the world. Be sure to check the copyright laws for your country before downloading or redistributing this or any other Project Gutenberg eBook. This header should be the first thing seen when viewing this Project Gutenberg file. Please do not remove it. Do not change or edit the header without written permission. Please read the "legal small print," and other information about the eBook and Project Gutenberg at the bottom of this file. Included is important information about your specific rights and restrictions in how the file may be used. You can also find out about how to make a donation to Project Gutenberg, and how to get involved. **Welcome To The World of Free Plain Vanilla Electronic Texts** **eBooks Readable By Both Humans and By Computers, Since 1971** *****These eBooks Were Prepared By Thousands of Volunteers!***** Title: Y Gododin Author: Aneurin Release Date: February, 2006 [EBook #9842] [This file was first posted on October 23, 2003] Edition: 10 Language: English Character set encoding: US-ASCII *** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK, Y GODODIN *** Transcribed by David Price, email [email protected] Y GODODIN PREFACE Aneurin, the author of this poem, was the son of Caw, lord of Cwm Cawlwyd, or Cowllwg, a region in the North, which, as we learn from a Life of Gildas in the monastery of Fleury published by Johannes a Bosco, comprehended Arecluta or Strath Clyde. {0a} Several of his brothers seem to have emigrated from Prydyn in company with their father before the battle of Cattraeth, and, under the royal protection of Maelgwn Gwynedd, to have settled in Wales, where they professed religious lives, and became founders of churches. -

The Animated Movie Guide

THE ANIMATED MOVIE GUIDE Jerry Beck Contributing Writers Martin Goodman Andrew Leal W. R. Miller Fred Patten An A Cappella Book Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Beck, Jerry. The animated movie guide / Jerry Beck.— 1st ed. p. cm. “An A Cappella book.” Includes index. ISBN 1-55652-591-5 1. Animated films—Catalogs. I. Title. NC1765.B367 2005 016.79143’75—dc22 2005008629 Front cover design: Leslie Cabarga Interior design: Rattray Design All images courtesy of Cartoon Research Inc. Front cover images (clockwise from top left): Photograph from the motion picture Shrek ™ & © 2001 DreamWorks L.L.C. and PDI, reprinted with permission by DreamWorks Animation; Photograph from the motion picture Ghost in the Shell 2 ™ & © 2004 DreamWorks L.L.C. and PDI, reprinted with permission by DreamWorks Animation; Mutant Aliens © Bill Plympton; Gulliver’s Travels. Back cover images (left to right): Johnny the Giant Killer, Gulliver’s Travels, The Snow Queen © 2005 by Jerry Beck All rights reserved First edition Published by A Cappella Books An Imprint of Chicago Review Press, Incorporated 814 North Franklin Street Chicago, Illinois 60610 ISBN 1-55652-591-5 Printed in the United States of America 5 4 3 2 1 For Marea Contents Acknowledgments vii Introduction ix About the Author and Contributors’ Biographies xiii Chronological List of Animated Features xv Alphabetical Entries 1 Appendix 1: Limited Release Animated Features 325 Appendix 2: Top 60 Animated Features Never Theatrically Released in the United States 327 Appendix 3: Top 20 Live-Action Films Featuring Great Animation 333 Index 335 Acknowledgments his book would not be as complete, as accurate, or as fun without the help of my ded- icated friends and enthusiastic colleagues.