Baiame's Cave and Creation Landscape, NSW, Australia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Finding Aid Available Here [797

O:\divisions\Cultural Collections @ UON\All Coll\NBN Television Archive\NBN PRODUCTIONS_TOPIC GROUPED\NEWS and ROVING EYE\2_VIDEOTAPE ... 1982 to 2019\BETACAM (1986 1999)Tapes\1B Betacam Tapes Film TITLE Other Information Date Track No. no. 1B_23 O.S. Sport Mentions Australian (Indigenous) player ‘Jamie Sandy’ 4/5/1986 4 (overseas) – Formerly from Redcliffe 1B_27 Art Gallery A few images of Indigenous art are prominent – 8/5/1986 7 though V/O glosses over. 1B_32 Peace Panel Panel includes Father Brian Gore (see 1B_26 – track 16/5/1986 2 5), Local Coordinator of Aboriginal Homecare Evelyn Barker – National Inquiry supported by the Aus council of Churches and Catholic Commission of Justice and Peace Human Rights issues. https://search.informit.org/fullText;dn=29384136395 4979;res=IELAPA This journal entry has an older photo on file. A quick google search indicates that Aunty Evelyn worked in Dubbo until her passing in 2014. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people should be aware that this footage contains images, voices or names of deceased persons in photographs, film, audio recordings or printed material. 1B_35 Boxing Includes images of an Indigenous Boxer: Roger Henry 28/5/1986 3 His record is attached: http://www.fightsrec.com/roger-henry.html 1B_40 Peace Bus Nuclear Disarmament. Bus itself includes a small 9/6/1986 9 painted Aboriginal flag along with native wildlife and forestry. Suggests a closer relationship between these groups 1B_42 Rail Exhibit Story on the rail line’s development and includes 13/6/1986 10 photos of workers. One of these is a photo of four men at ‘Jumbunna’ an Indigenous institute at UTS and another of rail line work. -

The Arunta a Study of Stone Age People

THE ARUNTA A STUDY OF STONE AGE PEOPLE BY SIR BALDWIN SPENCER, K.C.M.G., F.R.S. AND F.J. GILLEN IN TWO VOLUMES VOL., 1 1966 ANTHROPOLOGICAL PUBLICATIONS Oosterhoot N. B. – The Netherlands /414 The Arunta To our Master SIR JAMES FRAZER This record of A Stone Age People is offered in GRATITUDE AND ADMIRATION /414 page vii PREFACE AUSTRALIA is the present home and refuge of creatures, often crude and quaint, that have elsewhere passed away and given place to higher forms. This applies equally to the aboriginal as to the platypus and kangaroo. Just has the platypus laying its eggs and feebly suckling its young, reveal a mammals in the making,so does the Aboriginal show us, at least in a broad outline,what early man must have been like before he learned to read and write, domesticate animals, cultivate crops and use a metal tools. It has been possible to study in Australia human being that still remain on the culture level of men of stone age. The aim of this work is to give as complete and account as possible, based upon years of close study, of the organisation, customs, beliefs and general culture of a people that affords as much insight as we are now ever likely to gain into the manner of life of men and women who have long since disappeared in other part of the world and are now know to us only through their stone implements, with, rock drawings and more or less crude carvings, were the only imperishable records of their culture that they could leave behind them. -

![AR Radcliffe-Brown]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4080/ar-radcliffe-brown-684080.webp)

AR Radcliffe-Brown]

P129: The Personal Archives of Alfred Reginald RADCLIFFE-BROWN (1881- 1955), Professor of Anthropology 1926 – 1931 Contents Date Range: 1915-1951 Shelf Metre: 0.16 Accession: Series 2: Gift and deposit register p162 Alfred Reginald Radcliffe-Brown was born on 17 January 1881 at Aston, Warwickshire, England, second son of Alfred Brown, manufacturer's clerk and his wife Hannah, nee Radcliffe. He was educated at King Edward's School, Birmingham, and Trinity College, Cambridge (B.A. 1905, M. A. 1909), graduating with first class honours in the moral sciences tripos. He studied psychology under W. H. R. Rivers, who, with A. C. Haddon, led him towards social anthropology. Elected Anthony Wilkin student in ethnology in 1906 (and 1909), he spent two years in the field in the Andaman Islands. A fellow of Trinity (1908 - 1914), he lectured twice a week on ethnology at the London School of Economics and visited Paris where he met Emily Durkheim. At Cambridge on 19 April 1910 he married Winifred Marie Lyon; they were divorced in 1938. Radcliffe-Brown (then known as AR Brown) joined E. L. Grant Watson and Daisy Bates in an expedition to the North-West of Western Australia studying the remnants of Aboriginal tribes for some two years from 1910, but friction developed between Brown and Mrs. Bates. Brown published his research from that time in an article titled “Three Tribes of Western Australia”, The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, Vol. 43, (Jan. - Jun., 1913), pp. 143-194. At the 1914 meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science in Melbourne, Daisy Bates accused Brown of gross plagiarism. -

Our Knowledge for Country

2 2 STRENGTHENING OUR KNOWLEDGE FOR COUNTRY Authors: 2.1 INTRODUCTION TO CARING FOR COUNTRY 22 Barry Hunter, Aunty Shaa Smith, Neeyan Smith, Sarah Wright, Paul Hodge, Lara Daley, Peter Yates, Amelia Turner, 2.2 LISTENING AND TALKING WITH COUNTRY 23 Mia Mulladad, Rachel Perkins, Myf Turpin, Veronica Arbon, Eleanor McCall, Clint Bracknell, Melinda McLean, Vic 2.3 SINGING AND DANCING OUR COUNTRY 25 McGrath, Masigalgal Rangers, Masigalgal RNTBC, Doris 2.4 ART FOR COUNTRY 28 Yethun Burarrwaŋa, Bentley James, Mick Bourke, Nathan Wong, Yiyili Aboriginal Community School Board, John Hill, 2.5 BRINGING INDIGENOUS Wiluna Martu Rangers, Birriliburu Rangers, Kate Cherry, Darug LANGUAGES INTO ALL ASPECTS OF LIFE 29 Ngurra, Uncle Lex Dadd, Aunty Corina Norman-Dadd, Paul Glass, Paul Hodge, Sandie Suchet-Pearson, Marnie Graham, 2.6 ESTABLISHING CULTURAL Rebecca Scott, Jessica Lemire, Harriet Narwal, NAILSMA, KNOWLEDGE DATABASES AND ARCHIVES 35 Waanyi Garawa, Rosemary Hill, Pia Harkness, Emma Woodward. 2.7 BUILDING STRENGTH THROUGH KNOWLEDGE-RECORDING 36 2.8 WORKING WITH OUR CULTURAL HIGHLIGHTS HERITAGE, OBJECTS AND SITES 43 j Our Role in caring for Country 2.9 STRENGTHENING KNOWLEDGE j The importance of listening and hearing Country WITH OUR KIDS IN SCHOOLS 48 j The connection between language, songs, dance 2.10 WALKING OUR COUNTRY 54 and visual arts and Country 2.11 WALKING COUNTRY WITH j The role of Indigenous women in caring WAANYI GARAWA 57 for Country 2.12 LESSONS TOWARDS BEST j Keeping ancient knowledge for the future PRACTICE FROM THIS CHAPTER 60 j Modern technology in preserving, protecting and presenting knowledge j Unlocking the rich stories that our cultural heritage tell us about our past j Two-ways science ensuring our kids learn and grow within two knowledge systems – Indigenous and western science 21 2 STRENGTHENING OUR KNOWLEDGE FOR COUNTRY 2.1 INTRODUCTION TO CARING We do many different actions to manage and look after Country9,60,65,66. -

The Astronomy of the Kamilaroi and Euahlayi Peoples and Their Neighbours

The Astronomy of the Kamilaroi and Euahlayi Peoples and Their Neighbours By Robert Stevens Fuller A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Arts at Macquarie University for the degree of Master of Philosophy November 2014 © Robert Stevens Fuller i I certify that the work in this thesis entitled “The Astronomy of the Kamilaroi and Euahlayi Peoples and Their Neighbours” has not been previously submitted for a degree nor has it been submitted as part of requirements for a degree to any other university or institution other than Macquarie University. I also certify that the thesis is an original piece of research and it has been written by me. Any help and assistance that I have received in my research work and the preparation of the thesis itself has been appropriately acknowledged. In addition, I certify that all information sources and literature used are indicated in the thesis. The research presented in this thesis was approved by Macquarie University Ethics Review Committee reference number 5201200462 on 27 June 2012. Robert S. Fuller (42916135) ii This page left intentionally blank Contents Contents .................................................................................................................................... iii Dedication ................................................................................................................................ vii Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................... ix Publications .............................................................................................................................. -

Developing Identity As a Light-Skinned Aboriginal Person with Little Or No

Developing identity as a light-skinned Aboriginal person with little or no community and/or kinship ties. Bindi Bennett Bachelor Social Work Faculty of Health Sciences Australian Catholic University A thesis submitted to the ACU in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy 2015 1 Originality statement This thesis contains no material published elsewhere (except as detailed below) or extracted in whole or part from a thesis by which I have qualified for or been awarded another degree or diploma. No parts of this thesis have been submitted towards the award of any other degree or diploma in any other tertiary institution. No other person’s work has been used without due acknowledgment in the main text of the thesis. All research procedures reported in the thesis received the approval of the relevant Ethics Committees. This thesis was edited by Bruderlin MacLean Publishing Services. Chapter 2 was published during candidature as Chapter 1 of the following book Our voices : Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander social work / edited by Bindi Bennett, Sue Green, Stephanie Gilbert, Dawn Bessarab.South Yarra, Vic. : Palgrave Macmillan 2013. Some material from chapter 8 was published during candidature as the following article Bennett, B.2014. How do light skinned Aboriginal Australians experience racism? Implications for Social Work. Alternative. V10 (2). 2 Contents Contents .................................................................................................................................................... -

AIATSIS Subject Thesaurus

AIATSIS Subject Thesaurus December 2019 About AIATSIS – www.aiatsis.gov.au The Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (AIATSIS) is the world’s leading research, collecting and publishing organisation in Australian Indigenous studies. We are a network of council and committees, members, staff and other stakeholders working in partnership with Indigenous Australians to carry out activities that acknowledge, affirm and raise awareness of Australian Indigenous cultures and histories, in all their richness and diversity. AIATSIS develops, maintains and preserves well documented archives and collections and by maximising access to these, particularly by Indigenous peoples, in keeping with appropriate cultural and ethical practices. AIATSIS Thesaurus - Copyright Statement "This work is copyright. You may download, display, print and reproduce this material in unaltered form only (retaining this notice) for your personal, non-commercial use within your organisation. All other rights are reserved. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to The Library Director, The Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies, GPO Box 553, Canberra ACT 2601." AIATSIS Subject Thesaurus Introduction The AIATSIS thesauri have been made available to assist libraries, keeping places and Indigenous knowledge centres in indexing / cataloguing their collections using the most appropriate terms. This is also in accord with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Library and Information Research Network (ATSILIRN) Protocols - http://atsilirn.aiatsis.gov.au/protocols.php Protocol 4.1 states: “Develop, implement and use a national thesaurus for describing documentation relating to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and issues” We trust that the AIATSIS Thesauri will serve to assist in this task. -

DOCUMENTS in RETROSPECT Yearly Meeting 2018 7-14 July 2018 Avondale College Campus, Cooranbong NSW

The Religious Society of Friends (Quakers) in Australia Inc. DOCUMENTS in RETROSPECT Yearly Meeting 2018 7-14 July 2018 Avondale College Campus, Cooranbong NSW Photo by Geoff Greeves (SANTRM) Published by Australia Yearly Meeting 119 Devonshire Street, Surry Hills NSW 2010 Contents Abbreviations, Terms and Definitions 5 Yearly Meeting 2018 Epistles 8 Yearly Meeting 2018 Epistle to Friends Everywhere 8 2018 Yearly Meeting Children’s Program Epistle 10 2018 Yearly Meeting Junior Young Friends Epistle 11 Yearly Meeting 2018 Minutes 13 Formal Session 1: 7.30pm Saturday 7 July 13 YM18.1 Opening worship 13 YM18.2 Acknowledgement of Country Minute of Record 13 YM18.3 Clerking of Yearly Meeting 2018 13 YM18.4 Welcome to those participating in Yearly Meeting 13 YM18.5 Appointment of Assistant Co-Clerks 13 YM18.6 Appointments for the duration of YM18 14 YM18.7 Yearly Meeting timetable and agenda 15 YM18.8 Timeframe for Greetings from YM17 16 YM18.9 Letters and media releases sent on behalf of AYM 16 Formal Session 2: 7.15pm Sunday 8 July 18 YM18.10 State of the Society address: Minute of Record 18 YM18.11 Greetings sent to YM18 18 YM18.12 Backhouse Lecturer 2019 18 YM18.13 AYM Presiding Clerk’s Report 18 YM18.14 AYM Secretary’s Report 19 YM18.15 Acceptance of Reports that have no matters for consideration at YM18 19 YM18.16 Friends in Stitches publication launch Minute of Record 19 YM18.17 Nominations Committee Report 19 Formal Session 3: 9.30am Tuesday 10 July 20 YM18.18 Testimonies 20 YM18.19 Summary of Epistles 20 YM18.20 AYM Nominations 20 YM18.21 -

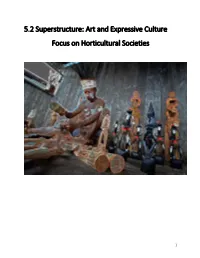

5.2UNIT FIVE Superstructure Art Expressive Culture Fall19

5.2 Superstructure: Art and Expressive Culture Focus on Horticultural Societies 1 Superstructure: Art and Expressive Culture Overview: This section covers aspects from the Cultural Materialist theory that relate to Superstructure: the beliefs that support the system. Topics include: Religion, Art, Music, Sports, Medicinal practices, Architecture. 2 ART M0010862 Navajo sand-painting, negative made from postcard Credit: Wellcome Library, London. Wellcome Images [email protected] http://wellcomeimages.org Navajo sand-painting, negative made from postcard, "All publication rights reserved. Apply to J.R. Willis, Gallup, N.M. Kodaks-Art Goods" (U.S.A.) Painting Published: - Copyrighted work available under Creative Commons Attribution only license CC BY 4.0 http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Key Terms & Concepts • Art • Visual arts • Anthropology of art • The problem of art • Purpose of art • Non-motivated purposes of art: basic human instinct, experience of the mysterious, expression of the imagination, ritualistic & symbolic • Motivated purposes of art: communication, entertainment, political, “free zone”, social inquiry, social causes, psychological/healing, propaganda/commercialism, fitness indicator • Paleolithic art: Blombos cave, figurative art, cave paintings, monumental open air art, petroglyphs • Tribal art: ethnographic art, “primitive art”, African art, Art of the Americas, Oceanic art • Folk art: Antique folk art, Contemporary folk art 3 • Indigenous Australian art: rock painting, Dot painting, Dreamtime, symbols • Sandpainting: Navajo, Tibetan Buddhist mandalas • Ethnomusicology • Dance • Native American Graves Protection And Repatriation Act (NAGPRA): cultural items Art Clockwise from upper left: a self-portrait by Vincent van Gogh; a female ancestor figure by a Chokwe artist; detail from The Birth of Venus by Sandro Botticelli; and an Okinawan Shisa lion. -

The Emu Sky Knowledge of the Kamilaroi and Euahlayi Peoples

Journal of Astronomical History and Heritage, Volume 17, Issue 2, Preprint. The Emu Sky Knowledge of the Kamilaroi and Euahlayi Peoples Robert S. Fuller1,2, Michael G. Anderson3, Ray P. Norris1,4, Michelle Trudgett1 1Warawara - Department of Indigenous Studies, Macquarie University, NSW, 2109, Australia Email: [email protected], [email protected] 2Macquarie University Research Centre for Astronomy, Astrophysics and Astrophotonics, Macquarie University, NSW, 2109, Australia 3Euahlayi Law Man, PO Box 55, Goodooga, NSW, 2838, Australia Email: [email protected] 4CSIRO Astronomy and Space Science, PO Box 76, Epping, NSW, 1710, Australia Email: [email protected] Abstract This paper presents a detailed study of the knowledge of the Kamilaroi and Euahlayi peoples about the Emu in the Sky. This study was done with ethnographic data that was not previously reported in detail. We surveyed the literature to find that there are widespread reports of an Emu in the Sky across Australian Aboriginal language groups, but little detailed knowledge available in the literature. This paper reports and describes a comprehensive Kamilaroi and Euahlayi knowledge of the Emu in the Sky and its cultural context. Notice to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Readers This paper contains the names of people who have passed away. 1. Introduction Cultural astronomy is the interdisciplinary study of how various cultures have understood and used astronomical phenomena, and the mechanisms by which this understanding is generated (Sinclair, 2006; Iwaniszewski, 2009). It is generally divided into archaeoastronomy (past cultures) and ethnoastronomy (contemporary cultures). Because cultural astronomy is a social science informed by the physical sciences (Ruggles, 2011), the field has been dubbed the “anthropology of astronomy” (Platt, 1991: S76). -

Week 7 Final.Pub

MORPETH PUBLIC SCHOOL Week 7, Term 4 24th November 2020 Phone - 4933 6726 email - [email protected] WEBSITE: Look what’s trending this week! www.morpeth‐p.schools.nsw.edu.au Field Events Carnival DATES TO REMEMBER Last Thursday’s field events carnival, held at Metford Oval, proved to be a resounding success. A team of 35 athletes participated in age based events including long jump, Monday 7th December shotput and discus on the day. At our corresponding carnival in 2019, a number of long Leadership speeches and voting standing records were broken. I am extremely proud to announce that history has repeated Friday 11th December itself and more students have etched their name into our record books. We will announce Kinder - Yr 5 Party Day the names of our event place getters, along with our new record holders, at Monday’s Yr 6 Party Day whole school assembly. Excursion to Baiame Cave Monday 14th December On Friday of last week, Mr Stewart and Mr Scanlan accompanied a group of students to Presentation Day Baiame Cave, in Milbrodale, to learn about Aboriginal culture. Upon arrival, our students Year 6 Farewell - 6pm - 8pm were welcomed onto country by Wonnarua elder Uncle Warren and cultural group Wednesday 16th December community leader, Michael. Uncle Warren and Michael performed a smoking ceremony Last day for students before our students listened intently to creation stories and about the meaning of the incredible artwork in the cave. Uncle Warren then provided first hand stories about his life as a Wonnarua person and spoke to our students about traditional tools and tool making, bush medicine, traditional hunting techniques, story telling and the importance of ceremonies. -

Aboriginal Spirituality: Aboriginal Philosophy the Basis of Aboriginal Social and Emotional Wellbeing

9 No. Aboriginal Spirituality: Aboriginal Philosophy The Basis of Aboriginal Social and Emotional Wellbeing Vicki Grieves Discussion Paper Series: Discussion Paper Aboriginal Spirituality provides a philosophical baseline for Indigenous knowledges development in Australia. It is Aboriginal knowledges that build the capacity to enhance the social and emotional wellbeing for Aboriginal people now living within a colonial regime. Cooperative Research Centre for Aboriginal Health Discussion Paper Series: No. 9 Aboriginal Spirituality: Aboriginal Philosophy The Basis of Aboriginal Social and Emotional Wellbeing Vicki Grieves © Cooperative Research Centre for Aboriginal Health, 2009 CRCAH Discussion Paper Series – ISSN 1834–156X ISBN 978–0–7340–4102–9 First printed in December 2009 This work has been published as part of the activities of the Cooperative Research Centre for Aboriginal Health (CRCAH). The CRCAH is a collaborative partnership partly funded by the Cooperative Research Centre Program of the Australian Government Department of Innovation, Industry, Science and Research. This work is copyright. It may be reproduced in whole or in part for study or training purposes, or by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Community organisations subject to an acknowledgment of the source and no commercial use or sale. Reproduction for other purposes or by other organisations requires the written permission of the copyright holder(s). Additional copies of this publication (including a pdf version on the CRCAH website) can be obtained from: Cooperative Research Centre for Aboriginal Health PO Box 41096, Casuarina NT 0811 AUSTRALIA T: +61 8 8943 5000 F: +61 8 8943 5010 E: [email protected] W: www.crcah.org.au Authors: Vicki Grieves Managing Editor: Jane Yule Copy Editor: Cathy Edmonds Cover photograph: Photograph of Alfred Coolwell by Vicki Grieves Original Design: Artifishal Studios Formatting and Printing: InPrint Design For citation: Grieves, V.