Spring 2002 Pt. 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tennessee Fish Species

The Angler’s Guide To TennesseeIncluding Aquatic Nuisance SpeciesFish Published by the Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency Cover photograph Paul Shaw Graphics Designer Raleigh Holtam Thanks to the TWRA Fisheries Staff for their review and contributions to this publication. Special thanks to those that provided pictures for use in this publication. Partial funding of this publication was provided by a grant from the United States Fish & Wildlife Service through the Aquatic Nuisance Species Task Force. Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency Authorization No. 328898, 58,500 copies, January, 2012. This public document was promulgated at a cost of $.42 per copy. Equal opportunity to participate in and benefit from programs of the Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency is available to all persons without regard to their race, color, national origin, sex, age, dis- ability, or military service. TWRA is also an equal opportunity/equal access employer. Questions should be directed to TWRA, Human Resources Office, P.O. Box 40747, Nashville, TN 37204, (615) 781-6594 (TDD 781-6691), or to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Office for Human Resources, 4401 N. Fairfax Dr., Arlington, VA 22203. Contents Introduction ...............................................................................1 About Fish ..................................................................................2 Black Bass ...................................................................................3 Crappie ........................................................................................7 -

Bowfin (Amia Calva)

Indiana Division of Fish and Wildlife’s Animal Information Series Bowfin (Amia calva) Do they have any other names? Other names for the bowfin are dogfish, grindle, grinnel, cypress trout, swamp muskie, black fish, cottonfish, swamp bass, poisson-castor, speckled cat, shoepic or choupic, and beaverfish. Why are they called bowfin? Amia is Greek for “fish” and calva is Greek for “bald or smooth” which refers to the bowfin’s scaleless head. The name “bowfin” refers to the long curved fin on the back of the fish. What do they look like? The bowfin is an elongate and nearly-cylindrical fish with a long dorsal (back) fin that extends from the middle of the back to the tail. The tail fin is rounded and has a black spot on the upper base of the tail. This black spot resembles an eye that predators will mistakenly attack, allowing the bowfin to get away. The back and tail fins are dark- green with darker bands or bars and the lower fins are bright green. The back and upper sides are mottled olive-green with pale green on the belly. The head is without scales but the body is covered in smooth-edged scales. They also have a large mouth with many sharp teeth and each nostril has a prominent barbel-like flap. Photo Credit: Duane Raver, USFWS 2012-MLC Page 1 Bowfin vs. Snakehead Bowfins are often mistaken as snakeheads, which are an exotic fish species native to Africa and Asia. Snakeheads are an aggressive invasive species that have little to no predators outside their native waters. -

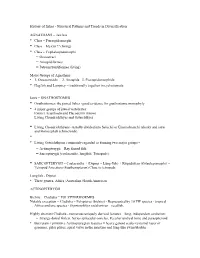

History of Fishes - Structural Patterns and Trends in Diversification

History of fishes - Structural Patterns and Trends in Diversification AGNATHANS = Jawless • Class – Pteraspidomorphi • Class – Myxini?? (living) • Class – Cephalaspidomorphi – Osteostraci – Anaspidiformes – Petromyzontiformes (living) Major Groups of Agnathans • 1. Osteostracida 2. Anaspida 3. Pteraspidomorphida • Hagfish and Lamprey = traditionally together in cyclostomata Jaws = GNATHOSTOMES • Gnathostomes: the jawed fishes -good evidence for gnathostome monophyly. • 4 major groups of jawed vertebrates: Extinct Acanthodii and Placodermi (know) Living Chondrichthyes and Osteichthyes • Living Chondrichthyans - usually divided into Selachii or Elasmobranchi (sharks and rays) and Holocephali (chimeroids). • • Living Osteichthyans commonly regarded as forming two major groups ‑ – Actinopterygii – Ray finned fish – Sarcopterygii (coelacanths, lungfish, Tetrapods). • SARCOPTERYGII = Coelacanths + (Dipnoi = Lung-fish) + Rhipidistian (Osteolepimorphi) = Tetrapod Ancestors (Eusthenopteron) Close to tetrapods Lungfish - Dipnoi • Three genera, Africa+Australian+South American ACTINOPTERYGII Bichirs – Cladistia = POLYPTERIFORMES Notable exception = Cladistia – Polypterus (bichirs) - Represented by 10 FW species - tropical Africa and one species - Erpetoichthys calabaricus – reedfish. Highly aberrant Cladistia - numerous uniquely derived features – long, independent evolution: – Strange dorsal finlets, Series spiracular ossicles, Peculiar urohyal bone and parasphenoid • But retain # primitive Actinopterygian features = heavy ganoid scales (external -

Recycled Fish Sculpture (.PDF)

Recycled Fish Sculpture Name:__________ Fish: are a paraphyletic group of organisms that consist of all gill-bearing aquatic vertebrate animals that lack limbs with digits. At 32,000 species, fish exhibit greater species diversity than any other group of vertebrates. Sculpture: is three-dimensional artwork created by shaping or combining hard materials—typically stone such as marble—or metal, glass, or wood. Softer ("plastic") materials can also be used, such as clay, textiles, plastics, polymers and softer metals. They may be assembled such as by welding or gluing or by firing, molded or cast. Researched Photo Source: Alaskan Rainbow STEP ONE: CHOOSE one fish from the attached Fish Names list. Trout STEP TWO: RESEARCH on-line and complete the attached K/U Fish Research Sheet. STEP THREE: DRAW 3 conceptual sketches with colour pencil crayons of possible visual images that represent your researched fish. STEP FOUR: Once your fish designs are approved by the teacher, DRAW a representational outline of your fish on the 18 x24 and then add VALUE and COLOUR . CONSIDER: Individual shapes and forms for the various parts you will cut out of recycled pop aluminum cans (such as individual scales, gills, fins etc.) STEP FIVE: CUT OUT using scissors the various individual sections of your chosen fish from recycled pop aluminum cans. OVERLAY them on top of your 18 x 24 Representational Outline 18 x 24 Drawing representational drawing to judge the shape and size of each piece. STEP SIX: Once you have cut out all your shapes and forms, GLUE the various pieces together with a glue gun. -

Bowfin DNR Information

Bowfin Did you know that Rock Lake is home to the prehistoric native fish species, the bowfin (Amia calva)? This fish is a living dinosaur. This fish was represented in middle Mesozoic strata over 100 million years ago. This is the only fish that survived from its family (Amiidae) of fishes from long ago. While primitive, the bowfin exhibits several evolutionary advances, including a gas bladder that can be used as a primitive lung (they can often be seen gulping air at the surface of the water), and specialized reproduction including male parental care (the male builds nests and guards the young for months). Not only is this fish a dinosaur, but it is important to the lake’s ecosystem. Bowfin are voracious, effective and opportunistic predators that have been mislabeled as a threat to panfish and sport fish populations. The bowfin is frequently found as part of the native fish fauna in many excellent sport and panfish waters in Wisconsin. In fact, studies have shown that the bowfin is effective in preventing stunting in sport fish populations. Bowfin have also been used as an additional predator in waters that are prone to overpopulation of carp and other rough fish species. Bowfin (native) The bowfin (commonly referred to as dogfish) has a large mouth equipped with many sharp teeth. Its large head has no scales. The dorsal fin is long, extending more than half the length of the back. The tail fin is rounded. There is a barbel-like flap associated with each nostril. The back is mottled olive green shading to lighter green on the belly. -

The Spotted Gar Genome Illuminates Vertebrate Evolution and Facilitates Human-To-Teleost Comparisons

Europe PMC Funders Group Author Manuscript Nat Genet. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2016 September 22. Published in final edited form as: Nat Genet. 2016 April ; 48(4): 427–437. doi:10.1038/ng.3526. Europe PMC Funders Author Manuscripts The spotted gar genome illuminates vertebrate evolution and facilitates human-to-teleost comparisons A full list of authors and affiliations appears at the end of the article. Abstract To connect human biology to fish biomedical models, we sequenced the genome of spotted gar (Lepisosteus oculatus), whose lineage diverged from teleosts before the teleost genome duplication (TGD). The slowly evolving gar genome conserved in content and size many entire chromosomes from bony vertebrate ancestors. Gar bridges teleosts to tetrapods by illuminating the evolution of immunity, mineralization, and development (e.g., Hox, ParaHox, and miRNA genes). Numerous conserved non-coding elements (CNEs, often cis-regulatory) undetectable in direct human-teleost comparisons become apparent using gar: functional studies uncovered conserved roles of such cryptic CNEs, facilitating annotation of sequences identified in human genome-wide association studies. Transcriptomic analyses revealed that the sum of expression domains and levels from duplicated teleost genes often approximate patterns and levels of gar genes, consistent with subfunctionalization. The gar genome provides a resource for understanding evolution after genome duplication, the origin of vertebrate genomes, and the function of human regulatory sequences. Europe PMC Funders Author Manuscripts Keywords GWAS; comparative medicine; polyploidy; zebrafish; medaka; neofunctionalization Teleost fish represent about half of all living vertebrate species1 and provide important models for human disease (e.g. zebrafish and medaka)2-9. -

![Kyfishid[1].Pdf](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2624/kyfishid-1-pdf-1462624.webp)

Kyfishid[1].Pdf

Kentucky Fishes Kentucky Department of Fish and Wildlife Resources Kentucky Fish & Wildlife’s Mission To conserve, protect and enhance Kentucky’s fish and wildlife resources and provide outstanding opportunities for hunting, fishing, trapping, boating, shooting sports, wildlife viewing, and related activities. Federal Aid Project funded by your purchase of fishing equipment and motor boat fuels Kentucky Department of Fish & Wildlife Resources #1 Sportsman’s Lane, Frankfort, KY 40601 1-800-858-1549 • fw.ky.gov Kentucky Fish & Wildlife’s Mission Kentucky Fishes by Matthew R. Thomas Fisheries Program Coordinator 2011 (Third edition, 2021) Kentucky Department of Fish & Wildlife Resources Division of Fisheries Cover paintings by Rick Hill • Publication design by Adrienne Yancy Preface entucky is home to a total of 245 native fish species with an additional 24 that have been introduced either intentionally (i.e., for sport) or accidentally. Within Kthe United States, Kentucky’s native freshwater fish diversity is exceeded only by Alabama and Tennessee. This high diversity of native fishes corresponds to an abun- dance of water bodies and wide variety of aquatic habitats across the state – from swift upland streams to large sluggish rivers, oxbow lakes, and wetlands. Approximately 25 species are most frequently caught by anglers either for sport or food. Many of these species occur in streams and rivers statewide, while several are routinely stocked in public and private water bodies across the state, especially ponds and reservoirs. The largest proportion of Kentucky’s fish fauna (80%) includes darters, minnows, suckers, madtoms, smaller sunfishes, and other groups (e.g., lam- preys) that are rarely seen by most people. -

Making a Big Splash with Louisiana Fishes

Making a Big Splash with Louisiana Fishes Written and Designed by Prosanta Chakrabarty, Ph.D., Sophie Warny, Ph.D., and Valerie Derouen LSU Museum of Natural Science To those young people still discovering their love of nature... Note to parents, teachers, instructors, activity coordinators and to all the fishermen in us: This book is a companion piece to Making a Big Splash with Louisiana Fishes, an exhibit at Louisiana State Universi- ty’s Museum of Natural Science (MNS). Located in Foster Hall on the main campus of LSU, this exhibit created in 2012 contains many of the elements discussed in this book. The MNS exhibit hall is open weekdays, from 8 am to 4 pm, when the LSU campus is open. The MNS visits are free of charge, but call our main office at 225-578-2855 to schedule a visit if your group includes 10 or more students. Of course the book can also be enjoyed on its own and we hope that you will enjoy it on your own or with your children or students. The book and exhibit was funded by the Louisiana Board Of Regents, Traditional Enhancement Grant - Education: Mak- ing a Big Splash with Louisiana Fishes: A Three-tiered Education Program and Museum Exhibit. Funding was obtained by LSUMNS Curators’ Sophie Warny and Prosanta Chakrabarty who designed the exhibit with Southwest Museum Services who built it in 2012. The oarfish in the exhibit was created by Carolyn Thome of the Smithsonian, and images exhibited here are from Curator Chakrabarty unless noted elsewhere (see Appendix II). -

Population Genetics of Bowfins (Amiidae, Amia Spp.) Across the Laurentian Great Lakes and the Carolinas

SUNY College of Environmental Science and Forestry Digital Commons @ ESF Honors Theses 12-2015 Population Genetics of Bowfins (Amiidae, Amia spp.) Across the Laurentian Great Lakes and the Carolinas Madeline J. Clark Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.esf.edu/honors Part of the Aquaculture and Fisheries Commons Recommended Citation Clark, Madeline J., "Population Genetics of Bowfins (Amiidae, Amia spp.) Across the Laurentian Great Lakes and the Carolinas" (2015). Honors Theses. 90. https://digitalcommons.esf.edu/honors/90 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ ESF. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ ESF. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Population Genetics of Bowfins (Amiidae, Amia spp.) Across the Laurentian Great Lakes and the Carolinas By Madeline J. Clark Candidate for Bachelor of Science Environmental and Forest Biology With Honors December 2015 APPROVED: Thesis Project Advisor: ______________________________ (Donald J. Stewart, Professor) Second Reader: ______________________________ (Steven M. Bogdanowicz, M.S.) Honors Director: _____________________________ William M. Shields, Professor Date: _____1 December 2015__________ 1 Abstract The Bowfin, Amia calva Linneaus (1766), is a common Eastern North American fish and the last extant member of the order Amiiformes. By 1870, twelve additional species of Bowfin had been described from widely dispersed localities from lakes Huron and Champlain in the north to Charleston, SC, and New Orleans, LA, in the south. This diversity of nominal forms was synonymized into a single species, A. calva, by Jordan and Evermann in 1896. Since then, this monotypy hypothesis has been generally accepted, but never scientifically validated. -

Checklist of Kansas Fishes

CHECKLIST OF KANSAS FISHES From "A Checklist of the Vertebrate Animals of Kansas", second edition, 1999, by George Potts, Joseph Collins and Kate Shaw (Species marked with an asterisk * are extirpated from the wild in Kansas.) 142 Species REFERENCE: Fishes in Kansas, 2nd edition, 1995 By Frank Cross and Joseph Collins, KU Press Order of Lampreys (Petromyzontiformes) Family Petromyzontidae Chestnut Lamprey - Ichthyomyzon castaneus Order of Sturgeons and Paddlefish (Acipenseriformes) Family Acipenseridae Lake Sturgeon - Acipenser fulvescens Pallid Sturgeon - Scaphirhynchus albus Shovelnose Sturgeon - Scaphirhynchus platorynchus Family Polyodontidae Paddlefish - Polyodon spathula Order of Gars (Semionotiformes) Family Lepisosteidae Spotted Gar - Lepisosteus oculatus Longnose Gar - Lepisosteus osseus Shortnose Gar - Lepisosteus platostomus Order of Bowfins (Amiiformes) Family Amiidae Bowfin - Amia calva Order of Bony-tongued fishes (Osteoglossiformes) Family Hiodontidae Goldeye - Hiodon alosoides * Mooneye - Hiodon tergisus Order of Eels (Anguilliformes) Family Anguillidae American Eel - Anguilla rostrata Order of Herrings (Clupeiformes) Family Clupeidae Skipjack Herring - Alosa chrysochloris Gizzard Shad - Dorosoma cepedianum Threadfin Shad - Dorosoma petenense Page 1 of 5 Order of Carp-like fishes (Cypriniformes) Family Cyprinidae Central Stoneroller - Campostoma anomalum Goldfish - Carassius auratus Grass Carp - Ctenopharyngodon idella Bluntface Shiner - Cyprinella camura Red Shiner - Cyprinella lutrensis Spotfin Shiner - Cyprinella spiloptera -

Kinematics of Ribbonfin Locomotion in the Bowfin, Amia Calva

RESEARCH ARTICLE Kinematics of Ribbon‐Fin Locomotion in the Bowfin, Amia calva 1,2 KEVIN JAGNANDAN * AND CHRISTOPHER P. SANFORD1 1Department of Biology, Hofstra University, Hempstead, New York 2Department of Evolution, Ecology and Organismal Biology, University of California, Riverside, California ABSTRACT An elongated dorsal and/or anal ribbon‐fin to produce forward and backward propulsion has independently evolved in several groups of fishes. In these fishes, fin ray movements along the fin generate a series of waves that drive propulsion. There are no published data on the use of the dorsal ribbon‐fin in the basal freshwater bowfin, Amia calva. In this study, frequency, amplitude, wavelength, and wave speed along the fin were measured in Amia swimming at different speeds (up to 1.0 body length/sec) to understand how the ribbon‐fin generates propulsion. These wave properties were analyzed to (1) determine whether regional specialization occurs along the ribbon‐ fin, and (2) to reveal how the undulatory waves are used to control swimming speed. Wave properties were also compared between swimming with sole use of the ribbon‐fin, and swimming with simultaneous use of the ribbon and pectoral fins. Statistical analysis of ribbon‐fin kinematics revealed no differences in kinematic patterns along the ribbon‐fin, and that forward propulsive speed in Amia is controlled by the frequency of the wave in the ribbon‐fin, irrespective of the contribution of the pectoral fin. This study is the first kinematic analysis of the ribbon‐fin in a basal fish and the model species for Amiiform locomotion, providing a basis for understanding ribbon‐fin locomotion among a broad range of teleosts. -

ASFIS ISSCAAP Fish List February 2007 Sorted on Scientific Name

ASFIS ISSCAAP Fish List Sorted on Scientific Name February 2007 Scientific name English Name French name Spanish Name Code Abalistes stellaris (Bloch & Schneider 1801) Starry triggerfish AJS Abbottina rivularis (Basilewsky 1855) Chinese false gudgeon ABB Ablabys binotatus (Peters 1855) Redskinfish ABW Ablennes hians (Valenciennes 1846) Flat needlefish Orphie plate Agujón sable BAF Aborichthys elongatus Hora 1921 ABE Abralia andamanika Goodrich 1898 BLK Abralia veranyi (Rüppell 1844) Verany's enope squid Encornet de Verany Enoploluria de Verany BLJ Abraliopsis pfefferi (Verany 1837) Pfeffer's enope squid Encornet de Pfeffer Enoploluria de Pfeffer BJF Abramis brama (Linnaeus 1758) Freshwater bream Brème d'eau douce Brema común FBM Abramis spp Freshwater breams nei Brèmes d'eau douce nca Bremas nep FBR Abramites eques (Steindachner 1878) ABQ Abudefduf luridus (Cuvier 1830) Canary damsel AUU Abudefduf saxatilis (Linnaeus 1758) Sergeant-major ABU Abyssobrotula galatheae Nielsen 1977 OAG Abyssocottus elochini Taliev 1955 AEZ Abythites lepidogenys (Smith & Radcliffe 1913) AHD Acanella spp Branched bamboo coral KQL Acanthacaris caeca (A. Milne Edwards 1881) Atlantic deep-sea lobster Langoustine arganelle Cigala de fondo NTK Acanthacaris tenuimana Bate 1888 Prickly deep-sea lobster Langoustine spinuleuse Cigala raspa NHI Acanthalburnus microlepis (De Filippi 1861) Blackbrow bleak AHL Acanthaphritis barbata (Okamura & Kishida 1963) NHT Acantharchus pomotis (Baird 1855) Mud sunfish AKP Acanthaxius caespitosa (Squires 1979) Deepwater mud lobster Langouste