Fairness Commissions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Combined Authorities and Metro Mayors

Combined Authorities and Metro Mayors What is a combined authority (CA)? A combined authority (CA) is a legal body set up using national legislation that enables a group of two or more councils to collaborate and take collective decisions across council boundaries. It is far more robust than an informal partnership or even a joint committee. The creation of a CA means that member councils can be more ambitious in their joint working and can take advantage of powers and resources devolved to them from national government. While established by Parliament, CAs are locally owned and have to be initiated and supported by the councils involved. 54 (17%) Number of local authorities (excluding the 33 London boroughs) with full membership of a combined authority 22% Percentage of population of England outside London living in a mayoral combined authority area Brief background to devolution and the combined authorities The idea of devolution has excited the imaginations of the political class for a long time even if the public has been less enthusiastic. The turnout rates for the May 2017 Metro Mayor 1 elections attest to this. Devolution was given a big push under New Labour but John Prescott’s North East Devolution Referendum 2004 was decisively rejected by the people (78% of voters were against). The idea was nevertheless pursued by the Coalition. Heseltine’s No Stone Unturned: In pursuit of growth 2012 report made a reasonable case for the concentration of funding streams and for these to be placed under local political control for greater efficiency and flexibility and to maximise effect. -

Liverpool City Council: Representation

Tony Reeves Chief Executive 24 May 2021 Catherine Frances Director General, Local Government, Strategy And Analysis Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government 2 Marsham Street London SW1P 4DF Dear Ms. Frances Liverpool City Council at its meeting on 19th May, considered the ‘Best Value’ Inspection Report undertaken by Max Caller, Mervyn Greer and Viviane Geary and your letter dated 24th March 2021 setting out the Secretary of State’s proposed intervention package for Liverpool. By unanimous agreement at Full Council, I have been instructed to send this letter outlining the council’s response, together with the detailed tables attached at Annex A. The Mayor and Leaders from all opposition parties are clear in their commitment to collectively leading the Council’s improvement journey and playing a full role in the design, implementation and monitoring of the Improvement Plan. The report acknowledges our openness and co-operation with the inspection team as they conducted their work and I would equally like to put on record, our thanks for their professionalism and subsequent ongoing support, as we develop our response to the report and improvement plans. As you will be aware, at our suggestion, we have consulted Max Caller on urgent property transactions. We are also doing so on the recruitment of a new City Solicitor and Monitoring Officer, resulting from the retirement of the current post holder. Max Caller has also been consulted on transitional arrangements for the Monitoring Officer position and either he or incoming Commissioners, will be involved in all further decisions leading up to the appointment of a new postholder. -

(Public Pack)Agenda Document for Liverpool City Region Combined

MEETING OF THE LIVERPOOL CITY REGION COMBINED AUTHORITY To: The Members of the Liverpool City Region Combined Authority Dear Member, You are requested to attend a meeting of the Liverpool City Region Combined Authority to be held on Friday, 22nd January, 2021 at 1.00pm. This meeting is being held remotely. The meeting will be live webcast. To access the webcast please go to the Combined Authority’s website at the time of the meeting and follow the instructions on the page. If you have any queries regarding this meeting, please contact Trudy Bedford on telephone number (0151) 330 1330. Yours faithfully Chief Executive WEBCASTING NOTICE This meeting will be filmed by the Combined Authority for live and/or subsequent broadcast on the Combined Authority’s website. The whole of the meeting will be filmed, except where there are confidential or exempt items. If you do not wish to have your image captured or if you have any queries regarding the webcasting of the meeting please contact the Democratic Services Officer on the above number or email [email protected]. A Fair Processing Notice is available on the Combined Authority’s website at https://www.liverpoolcityregion-ca.gov.uk/wp-content/uploads/Fair-Processing- Notice-CA-Meeting-Video-Recording.pdf. (Established pursuant to section 103 of the Local Democracy, Economic Development and Construction Act 2009 as the Halton, Knowsley, Liverpool, St Helens, Sefton and Wirral Combined Authority) LIVERPOOL CITY REGION COMBINED AUTHORITY AGENDA 1. APOLOGIES FOR ABSENCE 2. DECLARATIONS OF INTEREST 3. MINUTES OF THE MEETING OF THE LCR COMBINED AUTHORITY HELD ON 18 DECEMBER 2020 (Pages 1 - 10) 4. -

Inaugural Meeting

Inaugural meeting Tuesday 21st January, 12:30 to 13:00 in the Thatcher Room, Portcullis House NON-VERBATIM MINUTES Parliamentarians in attendance Alison McGovern, MP for Wirral South George Howarth, MP for Knowsley Margaret Greenwood, MP for Wirral West Conor McGinn, MP for St Helens North Paula Barker, MP for Liverpool Wavertree Mike Amesbury, MP for Weaver Valley Mick Whitley, MP for Birkenhead Derek Twigg, MP for Halton Ian Byrne, MP for West Darby Lord Alton of Liverpool Others Steve Rotheram, Metro Mayor, Liverpool city Region Rich Durber, Political Advisor to the Metro Mayor Steve Barwick, DevoConnect, Secretariat to APPG Gill Morris, DevoConnect, Secretariat to APPG Dean Butterworth, Liverpool Housing Providers Ciaran Tully, National Housing Federation NW Fiona Stanton, Northern Powerhouse Partnership Apologies Lord Heseltine Lord Hunt of the Wirral Baroness Newlove Baroness Chalker Kim Johnson MP Dan Carden MP Angela Eagle MP 1. Welcome and introductions Alison McGovern MP welcomed all attendees and informed them that the Group was set up in the last Parliament and had held meetings in Westminster and in Liverpool itself on transport, culture and the local industrial strategy as well as being a useful forum to know about LCRCA/Mayoral priorities and issues. The purpose of the APPG when initially established in 2018 was adopted for use in the new Parliamentary session: "to bring MPs and Peers of all parties together with key leaders, including the Liverpool City Region Metro Mayor and those in local government, the private sector and social enterprise, to help maximise future investment in the wider Liverpool City Region for the benefit of all its local communities." 2. -

Open PDF 250KB

Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy Committee Oral evidence: Post-pandemic economic growth: Levelling up – local and regional structures and the delivery of economic growth, HC 675 Thursday 22 October 2020 Ordered by the House of Commons to be published on 22 October 2020. Watch the meeting Members present: Darren Jones (Chair); Judith Cummins; Paul Howell; Charlotte Nichols; Mark Pawsey. Questions 57 - 87 Witnesses I: Rt Hon Andy Burnham, Mayor, Greater Manchester Combined Authority; Jamie Driscoll, Mayor, North of Tyne Combined Authority; Tim Bowles, Mayor, West of England Combined Authority; Steve Rotheram, Mayor, Liverpool City Region Combined Authority. Written evidence from witnesses: – [Greater Manchester Combined Authority (LRS0060)] Examination of Witnesses Witnesses: Andy Burnham, Jamie Driscoll, Tim Bowles and Steve Rotheram. Q57 Chair: Welcome to this morning’s session of the Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy Select Committee for our hearing today on levelling up and the delivery of regional growth. We are grateful this morning to have four busy, in-demand witnesses before the Committee: Andy Burnham, metro Mayor for Greater Manchester; Steve Rotheram, the equivalent metro Mayor for the Liverpool City Region; Tim Bowles from the West of England Combined Authority; and Jamie Driscoll from the North of Tyne Combined Authority. Welcome and good morning to all of you. Today we are going to split the session into an opening question on the impact of Covid on your regional economies and the functioning of the combined authorities, and then dive into some of the detail about how it has been going since you have been elected and what lessons might need to be learned for delivering the levelling-up agenda and the industrial strategy in the years to come. -

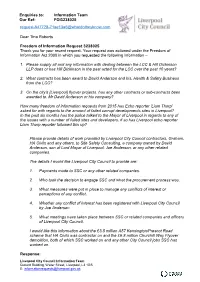

Enquiries To: Information Team Our Ref: FOI3238025 [email protected] Dear Tina Roberts Freedom of In

Enquiries to: Information Team Our Ref: FOI3238025 [email protected] Dear Tina Roberts Freedom of Information Request 3238025 Thank you for your recent request. Your request was actioned under the Freedom of Information Act 2000 in which you requested the following information – 1. Please supply all and any information with dealing between the LCC & Hill Dickinson LLP does or has Hill Dickinson in the past acted for the LCC over the past 10 years? 2. What contracts has been award to David Anderson and his, Health & Safety Business from the LCC? 3. On the city's [Liverpool] flyover projects, has any other contracts or sub-contracts been awarded to, Mr David Anderson or his company? How many freedom of information requests from 2015 has Echo reporter 'Liam Thorp' asked for with regards to the amount of failed corrupt developments sites in Liverpool? In the past six months has the police talked to the Mayor of Liverpool in regards to any of the issues with a number of failed sites and developers, if so has Liverpool echo reporter Liam Thorp reporter followed this up? Please provide details of work provided by Liverpool City Council contractors, Graham, HA Civils and any others, to Site Safety Consulting, a company owned by David Anderson, son of Lord Mayor of Liverpool, Joe Anderson, or any other related companies. The details I would like Liverpool City Council to provide are: 1. Payments made to SSC or any other related companies. 2. Who took the decision to engage SSC and what the procurement process was. -

Towards a Green Future for Liverpool City Region

A contribution to the ‘2019 Year of the Environment ‘Environmental Summit’, Liverpool City Region’ Towards a Green Future for Liverpool City Region Issues Paper Mark Boyle, Stephen Crone, Georgina Endfield, Susan Jarvis and Andrew McClelland | 3 CONTENTS 1. Confronting the climate and ecological crisis .................................................................................................................................................... 4 2. What are the challenges? ......................................................................................................................................................................................... 7 3. What is the United Kingdom doing to tackle the crisis and is it enough?................................................................................................13 4. What is being done in Liverpool City Region?...................................................................................................................................................15 a) Tackling the climate emergency: In search of a zero-carbon future ........................................................................................................16 b) In the face of species extinction: Supporting biodiversity ..........................................................................................................................21 c) Detox: Cleaning the air we breathe .................................................................................................................................................................26 -

Signatories to Debt Cancellation Statement

Signatories to debt cancellation statement Council Leaders Joe Anderson, Mayor of Liverpool Council Tom Beattie, Leader Corby Council 15 Julian Bell, Leader Ealing Council Matthew Brown, Leader Preston Council Doina Cornell, Leader Stroud District Council Shaun Davies, Leader Telford & Wrekin Council Chris Emmas-Williams, Leader Amber Valley Council Louise Gittins, Leader Cheshire West and Chester Pat Hackett, Leader Wirral Council Peter Marland, Leader Milton Keynes Council Shabir Pandor, Leader Kirklees Council Rob Polhill, Leader Halton Council Peter Soulsby, Mayor of Leicester Council Ian Ward, Leader Birmingham Council Alan Waters, Leader Norwich Council MPs Paula Barker, MP for Liverpool Wavertree Richard Burgon, MP for Leeds East 8 Ian Byrne, MP for Liverpool West Derby Clive Lewis, MP for Norwich South John McDonnell, MP for Hayes & Harlington Zarah Sultana, MP for Coventry South Claudia Webbe, MP for Leicester East Mick Whitley, MP for Birkenhead Opposition Labour Jim Grant, Labour Group Leader Swindon Borough Council Group Baggy Shanker, Leader Labour Group Derby Council Leaders/Deputies Kevin Stephens, Leader Labour Group Gloucester Council 3 Lead Members – Paul Bell, Cabinet Member for Housing Lewisham Council Housing Lynnie Hinnigan, Deputy Mayor of Liverpool, Housing 7 Philip O'Dell, Cabinet Member for Housing, Harrow Council Satvir Kaur, Cabinet Member for Homes & Culture, Southampton Council Mike Rowley, Portfolio Holder Housing, Oxford City Council Jeanette Thomas, Portfolio Holder for Housing, Health, and Older People, -

The Memory of Slavery in Liverpool in Public Discourse from the Nineteenth Century to the Present Day

The Memory of Slavery in Liverpool in Public Discourse from the Nineteenth Century to the Present Day Jessica Moody PhD University of York Department of History April 2014 Abstract This thesis maps the public, collective memory of slavery in Liverpool from the beginning of the nineteenth century to the present day. Using a discourse-analytic approach, the study draws on a wide range of ‘source genres’ to interrogate processes of collective memory across written histories, guidebooks, commemorative occasions and anniversaries, newspapers, internet forums, black history organisations and events, tours, museums, galleries and the built environment. By drawing on a range of material across a longue durée, the study contributes to a more nuanced understanding of how this former ‘slaving capital of the world’ has remembered its exceptional involvement in transatlantic slavery across a two hundred year period. This thesis demonstrates how Liverpool’s memory of slavery has evolved through a chronological mapping (Chapter Two) which places memory in local, national and global context(s). The mapping of memory across source areas is reflected within the structure of the thesis, beginning with ‘Mapping the Discursive Terrain’ (Part One), which demonstrates the influence and intertextuality of identity narratives, anecdotes, metaphors and debates over time and genre; ‘Moments of Memory’ (Part Two), where public commemorative occasions, anniversaries and moments of ‘remembrance’ accentuate issues of ‘performing’ identity and the negotiation of a dissonant past; and ‘Sites of Memory’ (Part Three), where debate and discourse around particular places in Liverpool’s contested urban terrain have forged multiple lieux de memoire (sites of memory) through ‘myths’ of slave bodies and contestations over race and representation. -

NORTH WEST REGIONAL CONFERENCE Blackpool Hilton Hotel, 4 - 5 November 2017

NORTH WEST REGIONAL CONFERENCE Blackpool Hilton Hotel, 4 - 5 November 2017 #LabNW17 Promoted by Anna Hutchinson on behalf of the North West Labour Party and North West Labour Party candidates all at 97 Spencer House, 81a Dewhurst Road, Birchwood, Warrington WA3 7PG. Printed by Greatledge Printers, Gorebrook Works, Pink Bank Lane, Longsight, Manchester, M12 5GH. TAMESIDE Cllr Maria Bailey 110,000 of the most vulnerable in Greater under the Tories? DELIVERED Manchester have beenFREE hit to by the Tory Bedroom Taxhomes in VOICE YOU AUDENSHAW Child care coststhe Tories have risen a whopping 30% under TAKEAWAY!The number of food banks have doubled in Tameside under the Tories I'm the only Tameside Voice The Tories and Liberal Democrats like to claim that families in Britain are better off. Just how Energyout bills of touch have can gone they be? politician keeping up £300,The on hard average,truth is that the for opposite is true. I know from speaking to constituents at my surgeries or in the street, TORYthe flame of Andrew GwynneTameside MPjust how householdshardWrites many people are still For finding things. The And I know Tameside that people across Tameside areVoice now more than under£1,600 athe year worseTories off under David Cameron. Many people living in communities like Audenshaw, Denton and Dukinfield are struggling to cope with the cost Thatcherism alive of living crisis. However hard they work, rising prices and stagnant wages mean that families are seeing a fall in TAMESIDE- Nigel Farage LOSES living standards and fewer opportunities for their children. www.greatledge.co.uk Tameside Voice David Cameron, George Osborne and Nick Clegg just do not understand the cost of living crisis facing hardworking £1 MILLION A WEEK families in Tameside. -

Local Housing Innovations

LOCAL HOUSING INNOVATIONS LOCAL HOUSING INNOVATIONS The Best of Labour in Power 2nd edition, HOUSING INNOVATIONS THE BEST OF LABOUR IN POWER 11 Spring 2017 CONTENTS 04. Introduction by John Healey MP 06. Birmingham City Council 26. Lancashire County Council A council-owned company which built its 2,000th new home A joint venture with the council’s pension fund in 2016 28. Liverpool City Council 08. Bristol City Council A scheme to turn dilapidated terraced houses into desirable, Council makes domestic abuse vicitms top priority for energy efficient homes social housing 30. London Borough of Barking and Dagenham 10. Cambridge City Council Right to invest, shared ownership of new homes for Interest-free loans of up to £25,000 to help bring empty council tenants properties back into residential use. 32. London Borough Of Croydon 12. City of Bradford District Council A council-owned housing development company aggregating Preventing homelessness through private sector lettings smaller sites for new homes 14. City of Wolverhampton Council 34. London Borough of Enfield A Trip Advisor-style rating scheme for landlords – Rent with Cost-effective temporary accommodation for homeless people Confidence – to empower residents 36. London Borough of Islington 16. Derby City Council Building genuinely affordable homes at scale Improving access to housing for homeless and hard to reach 38. London Borough of Newham young people A wholly-owned commercial development company to 18. Exeter City Council stimulate private rent and sale The council has set new ultra-high standards for healthy homes 40. Manchester City Council 20. Gateshead Council A partnership with Greater Manchester Pension Fund has built A £350million public-private partnership delivering 240 new homes 2,400 homes 42. -

'Slow Coup' Against Corbyn

Socialist Party | Print Livingstone suspension: 'Slow coup' against Corbyn Hannah Sell, Socialist Party deputy general secretary The furore around charges of antiSemitism engulfing the Labour Party is, in reality, an orchestrated and cynical new stage of the campaign by the rightwing procapitalist wing of the Labour Party to try and prepare the ground for ditching Jeremy Corbyn at the earliest possible opportunity. It is not possible to tell what the timescale will be, but this has all the hallmarks of a slow coup. Iain Watson, the BBC's Political Correspondent, reports a Labour MP telling him a week before this broke publicly that: "There is a lot more in this antiSemitism issue a lot more. And the people we will take out are all close to Corbyn." Jeremy Corbyn was elected less than a year ago by a landslide; having enthused hundreds of thousands of people with his antiausterity policies. The Blairites were trounced and these 4.5%ers were horrified at the prospect of Labour a party whose leadership had loyally acted in the interests of big business for decades being reclaimed by the working class. Backed to the hilt by big business and the rightwing media, they are dedicating all their time and energy into once again making Labour a party that can be relied on to act in the interests of the 1%. Compromise no solution As we have repeatedly warned, no amount of attempts to compromise with the right wing that dominates the parliamentary Labour Party will pacify them. On the contrary it only emboldens them.