The TUSC Results

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Combined Authorities and Metro Mayors

Combined Authorities and Metro Mayors What is a combined authority (CA)? A combined authority (CA) is a legal body set up using national legislation that enables a group of two or more councils to collaborate and take collective decisions across council boundaries. It is far more robust than an informal partnership or even a joint committee. The creation of a CA means that member councils can be more ambitious in their joint working and can take advantage of powers and resources devolved to them from national government. While established by Parliament, CAs are locally owned and have to be initiated and supported by the councils involved. 54 (17%) Number of local authorities (excluding the 33 London boroughs) with full membership of a combined authority 22% Percentage of population of England outside London living in a mayoral combined authority area Brief background to devolution and the combined authorities The idea of devolution has excited the imaginations of the political class for a long time even if the public has been less enthusiastic. The turnout rates for the May 2017 Metro Mayor 1 elections attest to this. Devolution was given a big push under New Labour but John Prescott’s North East Devolution Referendum 2004 was decisively rejected by the people (78% of voters were against). The idea was nevertheless pursued by the Coalition. Heseltine’s No Stone Unturned: In pursuit of growth 2012 report made a reasonable case for the concentration of funding streams and for these to be placed under local political control for greater efficiency and flexibility and to maximise effect. -

Final Recommendations on the Future Electoral Arrangements for Wakefield

Final recommendations on the future electoral arrangements for Wakefield Report to The Electoral Commission July 2003 © Crown Copyright 2003 Applications for reproduction should be made to: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office Copyright Unit. The mapping in this report is reproduced from OS mapping by The Electoral Commission with the permission of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, © Crown Copyright. Unauthorised reproduction infringes Crown Copyright and may lead to prosecution or civil proceedings. Licence Number: GD 03114G. This report is printed on recycled paper. Report no. 342 2 Contents Page What is The Boundary Committee For England? 5 Summary 7 1 Introduction 13 2 Current electoral arrangements 15 3 Draft recommendations 19 4 Responses to consultation 21 5 Analysis and final recommendations 23 6 What happens next? 67 Appendices A Final recommendations for Wakefield: Detailed mapping 69 B First draft of electoral change Order for Wakefield 71 C Guide to interpreting the first draft of the electoral Order 76 3 4 What is The Boundary Committee for England? The Boundary Committee for England is a committee of The Electoral Commission, an independent body set up by Parliament under the Political Parties, Elections and Referendums Act 2000. The functions of the Local Government Commission for England were transferred to The Electoral Commission and its Boundary Committee on 1 April 2002 by the Local Government Commission for England (Transfer of Functions) Order 2001 (SI 2001 no. 3692). The Order also transferred to The Electoral Commission the functions of the Secretary of State in relation to taking decisions on recommendations for changes to local authority electoral arrangements and implementing them. -

Liverpool City Council: Representation

Tony Reeves Chief Executive 24 May 2021 Catherine Frances Director General, Local Government, Strategy And Analysis Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government 2 Marsham Street London SW1P 4DF Dear Ms. Frances Liverpool City Council at its meeting on 19th May, considered the ‘Best Value’ Inspection Report undertaken by Max Caller, Mervyn Greer and Viviane Geary and your letter dated 24th March 2021 setting out the Secretary of State’s proposed intervention package for Liverpool. By unanimous agreement at Full Council, I have been instructed to send this letter outlining the council’s response, together with the detailed tables attached at Annex A. The Mayor and Leaders from all opposition parties are clear in their commitment to collectively leading the Council’s improvement journey and playing a full role in the design, implementation and monitoring of the Improvement Plan. The report acknowledges our openness and co-operation with the inspection team as they conducted their work and I would equally like to put on record, our thanks for their professionalism and subsequent ongoing support, as we develop our response to the report and improvement plans. As you will be aware, at our suggestion, we have consulted Max Caller on urgent property transactions. We are also doing so on the recruitment of a new City Solicitor and Monitoring Officer, resulting from the retirement of the current post holder. Max Caller has also been consulted on transitional arrangements for the Monitoring Officer position and either he or incoming Commissioners, will be involved in all further decisions leading up to the appointment of a new postholder. -

(Public Pack)Agenda Document for Liverpool City Region Combined

MEETING OF THE LIVERPOOL CITY REGION COMBINED AUTHORITY To: The Members of the Liverpool City Region Combined Authority Dear Member, You are requested to attend a meeting of the Liverpool City Region Combined Authority to be held on Friday, 22nd January, 2021 at 1.00pm. This meeting is being held remotely. The meeting will be live webcast. To access the webcast please go to the Combined Authority’s website at the time of the meeting and follow the instructions on the page. If you have any queries regarding this meeting, please contact Trudy Bedford on telephone number (0151) 330 1330. Yours faithfully Chief Executive WEBCASTING NOTICE This meeting will be filmed by the Combined Authority for live and/or subsequent broadcast on the Combined Authority’s website. The whole of the meeting will be filmed, except where there are confidential or exempt items. If you do not wish to have your image captured or if you have any queries regarding the webcasting of the meeting please contact the Democratic Services Officer on the above number or email [email protected]. A Fair Processing Notice is available on the Combined Authority’s website at https://www.liverpoolcityregion-ca.gov.uk/wp-content/uploads/Fair-Processing- Notice-CA-Meeting-Video-Recording.pdf. (Established pursuant to section 103 of the Local Democracy, Economic Development and Construction Act 2009 as the Halton, Knowsley, Liverpool, St Helens, Sefton and Wirral Combined Authority) LIVERPOOL CITY REGION COMBINED AUTHORITY AGENDA 1. APOLOGIES FOR ABSENCE 2. DECLARATIONS OF INTEREST 3. MINUTES OF THE MEETING OF THE LCR COMBINED AUTHORITY HELD ON 18 DECEMBER 2020 (Pages 1 - 10) 4. -

Reconstructing Public Housing Liverpool’S Hidden History of Collective Alternatives

Reconstructing Public Housing Liverpool’s hidden history of collective alternatives Reconstructing Public Housing Liverpool’s hidden history of collective alternatives Reconstructing Public Housing Matthew Thompson LIVERPOOL UNIVERSITY PRESS First published 2020 by Liverpool University Press 4 Cambridge Street Liverpool L69 7ZU Copyright © 2020 Matthew Thompson The right of Matthew Thompson to be identified as the author of this book has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication data A British Library CIP record is available ISBN 978-1-78962-108-2 paperback eISBN 978-1-78962-740-4 Typeset by Carnegie Book Production, Lancaster An Open Access edition of this book is available on the Liverpool University Press website and the OAPEN library. Contents Contents List of Figures ix List of Abbreviations x Acknowledgements xi Prologue xv Part I Introduction 1 Introducing Collective Housing Alternatives 3 Why Collective Housing Alternatives? 9 Articulating Our Housing Commons 14 Bringing the State Back In 21 2 Why Liverpool of All Places? 27 A City of Radicals and Reformists 29 A City on (the) Edge? 34 A City Playing the Urban Regeneration Game 36 Structure of the Book 39 Part II The Housing Question 3 Revisiting -

Inaugural Meeting

Inaugural meeting Tuesday 21st January, 12:30 to 13:00 in the Thatcher Room, Portcullis House NON-VERBATIM MINUTES Parliamentarians in attendance Alison McGovern, MP for Wirral South George Howarth, MP for Knowsley Margaret Greenwood, MP for Wirral West Conor McGinn, MP for St Helens North Paula Barker, MP for Liverpool Wavertree Mike Amesbury, MP for Weaver Valley Mick Whitley, MP for Birkenhead Derek Twigg, MP for Halton Ian Byrne, MP for West Darby Lord Alton of Liverpool Others Steve Rotheram, Metro Mayor, Liverpool city Region Rich Durber, Political Advisor to the Metro Mayor Steve Barwick, DevoConnect, Secretariat to APPG Gill Morris, DevoConnect, Secretariat to APPG Dean Butterworth, Liverpool Housing Providers Ciaran Tully, National Housing Federation NW Fiona Stanton, Northern Powerhouse Partnership Apologies Lord Heseltine Lord Hunt of the Wirral Baroness Newlove Baroness Chalker Kim Johnson MP Dan Carden MP Angela Eagle MP 1. Welcome and introductions Alison McGovern MP welcomed all attendees and informed them that the Group was set up in the last Parliament and had held meetings in Westminster and in Liverpool itself on transport, culture and the local industrial strategy as well as being a useful forum to know about LCRCA/Mayoral priorities and issues. The purpose of the APPG when initially established in 2018 was adopted for use in the new Parliamentary session: "to bring MPs and Peers of all parties together with key leaders, including the Liverpool City Region Metro Mayor and those in local government, the private sector and social enterprise, to help maximise future investment in the wider Liverpool City Region for the benefit of all its local communities." 2. -

Open PDF 250KB

Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy Committee Oral evidence: Post-pandemic economic growth: Levelling up – local and regional structures and the delivery of economic growth, HC 675 Thursday 22 October 2020 Ordered by the House of Commons to be published on 22 October 2020. Watch the meeting Members present: Darren Jones (Chair); Judith Cummins; Paul Howell; Charlotte Nichols; Mark Pawsey. Questions 57 - 87 Witnesses I: Rt Hon Andy Burnham, Mayor, Greater Manchester Combined Authority; Jamie Driscoll, Mayor, North of Tyne Combined Authority; Tim Bowles, Mayor, West of England Combined Authority; Steve Rotheram, Mayor, Liverpool City Region Combined Authority. Written evidence from witnesses: – [Greater Manchester Combined Authority (LRS0060)] Examination of Witnesses Witnesses: Andy Burnham, Jamie Driscoll, Tim Bowles and Steve Rotheram. Q57 Chair: Welcome to this morning’s session of the Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy Select Committee for our hearing today on levelling up and the delivery of regional growth. We are grateful this morning to have four busy, in-demand witnesses before the Committee: Andy Burnham, metro Mayor for Greater Manchester; Steve Rotheram, the equivalent metro Mayor for the Liverpool City Region; Tim Bowles from the West of England Combined Authority; and Jamie Driscoll from the North of Tyne Combined Authority. Welcome and good morning to all of you. Today we are going to split the session into an opening question on the impact of Covid on your regional economies and the functioning of the combined authorities, and then dive into some of the detail about how it has been going since you have been elected and what lessons might need to be learned for delivering the levelling-up agenda and the industrial strategy in the years to come. -

Week School on Political Issues from the History of AWL

Week school on political issues from the history of AWL Day One Session: Heterodox, orthodox, and “orthodox Mark 2” 1. Why we started: 1966-8 Trotskyism: http://www.workersliberty.org//taxonomy/term/555 http://www.workersliberty.org/wwaawwmb The AWL's tradition: http://www.workersliberty.org/node/5146 Session: Party and perspectives What happened in 1968 and how the left responded ***************** Why we fused with IS (SWP) Timeline 2. Ireland: 1968-71 1964 July 2: After years of civil rights agitation in USA, Civil Rights http://www.workersliberty.org/node/10010 Act becomes law. October 15: Labour wins general election, after 13 years of Session: The debates in 1969 - “withdraw subsidies”, Tory rule “southern arsenals”, “troops out” before August 1969, “Catholic economism” and transitional demands, “troops out” 1965 in August 1969. January 31: USA starts bombing of North Vietnam. Vietnam war, and movement against it, escalate. Day Two February: SLL, then biggest revolutionary group in Britain, launches its own independent "Young Socialists" as a 3. The Tories and Labour 1970-4 response to limited expulsions by Labour Party after SLL wins majority in Labour youth movement. Session: General strike Our Labour Party debate then: syndicalism, economism, and 1966 politics Summer: Beginning of "Cultural Revolution" in China: a faction of the bureaucracy mobilises gangs to purge rivals 4. Stalinism 1968-75 reinforce autarkic, ultra-statist policy. But many leftists in the West will admire the "Cultural Revolution"; Maoism will Session: Czechoslovakia 1968 be a big force on the revolutionary left from 1968 to the “Soviet dissidents” mid-70s, though less so in Britain than in other European Vietnam and Cambodia 1975 countries. -

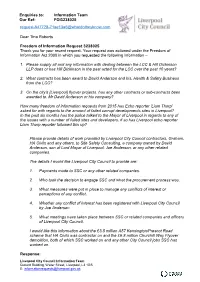

Enquiries To: Information Team Our Ref: FOI3238025 [email protected] Dear Tina Roberts Freedom of In

Enquiries to: Information Team Our Ref: FOI3238025 [email protected] Dear Tina Roberts Freedom of Information Request 3238025 Thank you for your recent request. Your request was actioned under the Freedom of Information Act 2000 in which you requested the following information – 1. Please supply all and any information with dealing between the LCC & Hill Dickinson LLP does or has Hill Dickinson in the past acted for the LCC over the past 10 years? 2. What contracts has been award to David Anderson and his, Health & Safety Business from the LCC? 3. On the city's [Liverpool] flyover projects, has any other contracts or sub-contracts been awarded to, Mr David Anderson or his company? How many freedom of information requests from 2015 has Echo reporter 'Liam Thorp' asked for with regards to the amount of failed corrupt developments sites in Liverpool? In the past six months has the police talked to the Mayor of Liverpool in regards to any of the issues with a number of failed sites and developers, if so has Liverpool echo reporter Liam Thorp reporter followed this up? Please provide details of work provided by Liverpool City Council contractors, Graham, HA Civils and any others, to Site Safety Consulting, a company owned by David Anderson, son of Lord Mayor of Liverpool, Joe Anderson, or any other related companies. The details I would like Liverpool City Council to provide are: 1. Payments made to SSC or any other related companies. 2. Who took the decision to engage SSC and what the procurement process was. -

Urgent Care at Pontefract Hospital 2017

Urgent Care at Pontefract Hospital 2017 Nichola Esmond Chief Executive Officer September 2017 This report and information in it can be used or reproduced however please ensure the information used is credited to Healthwatch Wakefield. Contents Pontefract Hospital emergency care provision since 2011 .......................................................................................... 4 Purpose of the engagement ......................................................................................................................................... 5 Next steps ..................................................................................................................................................................... 5 Key Findings .................................................................................................................................................................. 6 What happens currently across Wakefield District? .................................................................................................... 8 National Guidance about urgent care .......................................................................................................................... 8 The difference between A&E (or Emergency Department) and Urgent Treatment Centre .................................... 8 Responsibilities of the CCG, including legal requirements ........................................................................................... 9 Legal requirements .................................................................................................................................................. -

Towards a Green Future for Liverpool City Region

A contribution to the ‘2019 Year of the Environment ‘Environmental Summit’, Liverpool City Region’ Towards a Green Future for Liverpool City Region Issues Paper Mark Boyle, Stephen Crone, Georgina Endfield, Susan Jarvis and Andrew McClelland | 3 CONTENTS 1. Confronting the climate and ecological crisis .................................................................................................................................................... 4 2. What are the challenges? ......................................................................................................................................................................................... 7 3. What is the United Kingdom doing to tackle the crisis and is it enough?................................................................................................13 4. What is being done in Liverpool City Region?...................................................................................................................................................15 a) Tackling the climate emergency: In search of a zero-carbon future ........................................................................................................16 b) In the face of species extinction: Supporting biodiversity ..........................................................................................................................21 c) Detox: Cleaning the air we breathe .................................................................................................................................................................26 -

Libya, Anti-Imperialism, and the Socialist Party

Published on Workers' Liberty (http://www.workersliberty.org) Libya, anti-imperialism, and the Socialist Party By Sean Matgamna This is a copy-edited and slightly expanded version of the text printed in WL 3/34 Libya, anti-imperialism, and the Socialist Party Did Taaffe equate the Libyan rebels with the Nicaraguan contras? [3] Anything other than "absolute opposition" means support? [4] Intellectual hooliganism and AWL's "evasions" [5] What is more important in the situation than stopping massacre? [6] Bishop Taaffe and imperialism [7] What is the "anti-imperialist" programme in today's world? [8] From semi-colony to regional power [9] Taaffe's record as an anti-imperialist [10] The separation of AWL and the Socialist Party [11] Militant in the mid 1960s [12] How did we come to break with Militant? Anti-union laws [13] What is a Marxist perspective? [14] Peaceful revolution [15] Our general critique of Militant's politics [16] "We can't discuss what Grant and Taaffe can't reply to" [17] The US in Iraq and union freedoms [18] Socialists and the European Union [19] Toadying to Bob Crow [20] Ireland: why socialists must have a democratic programme [21] Conclusion: Pretension [22] Appendix: Militant and the Labour Party, 1969-87 - a strange symbiosis [23] What We Are And What We Must Become: critique of Militant, written in 1966, which became the founding document of the AWL tendency, is available at http://www.workersliberty.org/wwaawwmb The RSL (Militant) in the 1960s: a study of passivity: an account of how What We Are And What We Must Become came to be written, and the battle around its ideas.