The Grass-Roots Urbanism of the Hindu Temple

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Circumambulation in Indian Pilgrimage: Meaning And

232 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF SCIENTIFIC & ENGINEERING RESEARCH, VOLUME 12, ISSUE 1, JANUARY-2021 ISSN 2229-5518 Circumambulation in Indian pilgrimage: Meaning and manifestation Santosh Kumar Abstract— Our ancient literature is full of examples where pilgrimage became an immensely popular way of achieving spiritual aims while walking. In India, many communities have attached spiritual importance to particular places or to the place where people feel a spiritual awakening. Circumambulation (pradakshina) around that sacred place becomes the key point of prayer and offering. All these circumambulation spaces are associated with the shrines or sacred places referring to auspicious symbolism. In Indian tradition, circumambulation has been practice in multiple scales ranging from a deity or tree to sacred hill, river, and city. The spatial character of the path, route, and street, shift from an inside dwelling to outside in nature or city, depending upon the central symbolism. The experience of the space while walking through sacred space remodel people's mental and physical character. As a result, not only the sacred space but their design and physical characteristics can be both meaningful and valuable to the public. This research has been done by exploring in two stage to finalize the conclusion, In which First stage will involve a literature exploration of Hindu and Buddhist scripture to understand the meaning and significance of circumambulation and in second, will investigate the architectural manifestation of various element in circumambulatory which help to attain its meaning and true purpose. Index Terms— Pilgrimage, Circumambulation, Spatial, Sacred, Path, Hinduism, Temple architecture —————————— —————————— 1 Introduction Circumambulation ‘Pradakshinā’, According to Rig Vedic single light source falling upon central symbolism plays a verses1, 'Pra’ used as a prefix to the verb and takes on the vital role. -

Perhaps Do a Series and Take One Particular Subject at a Time

perhaps do a series and take one particular subject at a time. Sadhguru just as I was coming to see you I saw this little piece in one of the newspapers which said that one doesn’t know about India being a super power but when it comes to mysticism, the world looks to Indian gurus as the help button on the menu. You’ve been all over the world and spoken at many international events, what is your take on all the divine gurus traversing the globe these days? India as a culture has invested more time, energy and human resource toward the spiritual development of human beings for a very long time. This can only happen when there is a stable society for long periods without much strife. While all other societies were raked by various types of wars, and revolutions, India remained peaceful for long periods of time. So they invested that time in spiritual development, and it became the day to day ethos of every Indian. The world looking towards India for spiritual help is nothing new. It has always been so in terms of exploring the inner spaces of a human being-how a human being is made, what is his potential, where could he be taken in terms of his experiences. I don’t think any culture has looked into this with as much depth and variety as India has. Mark Twain visited India and after spending three months and visiting all the right places with his guide he paid India the ultimate compliment when he said that anything that can ever be done by man or God has been done in this land. -

In the Name of Krishna: the Cultural Landscape of a North Indian Pilgrimage Town

In the Name of Krishna: The Cultural Landscape of a North Indian Pilgrimage Town A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Sugata Ray IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Frederick M. Asher, Advisor April 2012 © Sugata Ray 2012 Acknowledgements They say writing a dissertation is a lonely and arduous task. But, I am fortunate to have found friends, colleagues, and mentors who have inspired me to make this laborious task far from arduous. It was Frederick M. Asher, my advisor, who inspired me to turn to places where art historians do not usually venture. The temple city of Khajuraho is not just the exquisite 11th-century temples at the site. Rather, the 11th-century temples are part of a larger visuality that extends to contemporary civic monuments in the city center, Rick suggested in the first class that I took with him. I learnt to move across time and space. To understand modern Vrindavan, one would have to look at its Mughal past; to understand temple architecture, one would have to look for rebellions in the colonial archive. Catherine B. Asher gave me the gift of the Mughal world – a world that I only barely knew before I met her. Today, I speak of the Islamicate world of colonial Vrindavan. Cathy walked me through Mughal mosques, tombs, and gardens on many cold wintry days in Minneapolis and on a hot summer day in Sasaram, Bihar. The Islamicate Krishna in my dissertation thus came into being. -

Redalyc.The Universalization of the Bhakti Yoga of Chaytania

VIBRANT - Vibrant Virtual Brazilian Anthropology E-ISSN: 1809-4341 [email protected] Associação Brasileira de Antropologia Brasil Silva da Silveira, Marcos The Universalization of the Bhakti Yoga of Chaytania Mahaprabhu. Ethnographic and Historic Considerations VIBRANT - Vibrant Virtual Brazilian Anthropology, vol. 11, núm. 2, diciembre, 2014, pp. 371-405 Associação Brasileira de Antropologia Brasília, Brasil Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=406941918013 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative The Universalization of the Bhakti Yoga of Chaytania Mahaprabhu Ethnographic and Historic Considerations Marcos Silva da Silveira Abstract Inspired by Victor Turner’s concepts of structure and communitas, this article commences with an analysis of the Gaudiya Vaishnavas – worshipers of Radha, and Krishna Chaitanya Mahaprabhu followers. Secondly, we present data from ethnographic research conducted with South American devotees on pilgrimage to the ceremonial center ISCKON in Mayapur, West Bengal, during the year 1996, for a resumption of those initial considerations. The article seeks to demonstrate that the ritual injunction characteristic of Hindu sects, only makes sense from the individual experience of each devotee. Keywords: religion, Hinduism, New Age, Hare Krishna, ritual process Resumo Este artigo trata de revisitar o conceito consagrado de Victor Turner Estrutura – Communitas , tendo, como ponto de partida, uma análise de seus estudos de caso do Leste da Índia , em particular, entre os Gaudiya Vaishnavas – adoradores de Radha e Krishna, seguidores de Chaitanya Mahaprabhu. -

Chapter 6: EPILOGUE I. Significance of the Study A) the Study Is Basically

Chapter 6: EPILOGUE I. Significance of the study a) The study is basically a very good documentation of Goa's ancient and medieval period icons and sculptural remains. So far a wrong notion among many that Goa religio cultural past before the arrival of the Portuguese is intangible has been critically viewed and examined in this study. The research would help in throwing light on the pre-Portuguese era of the Goa's history. b) The craze of modernization and renovation of ancient and historic temples have made changes in the religio-cultural aspect of the society. Age old deities and concepts of worships have been replaced with new sculptures or icons. The new sculptures installed in places of the historic ones have been modified to the whims and fancies of many trustees or temple authorities thus changing the pattern of the religio-cultural past. While new icons substitute the old ones there are changes in attributes, styles and the historic features of the sculpture or image. Not just this but the old sculptures are immersed in water when the new one is being installed. Some customary rituals have been rapidly changed intentionally or unintentionally by the stake holders or the devotees. Moreover the most of the ancient rituals and customs associated with some icons have are in process of being stopped by the locals. Therefore a thorough documentation of these sculptures and antiquities with scientific attitude and research was the need of the hour. c) The iconographic details about many sculptures, worships or deities are scattered in many books and texts. -

(Korra): Holy Mt Kailash and Mansarovar Lake

27 - A/C, GANDHI NAGAR, JAMMU - 180004 (J&K) INDIA. Tele:- +91-191-2430662, 2452309, 2456656. Fax:- +91-191-2456656. Website: - www.mastertoursindia.com. Email: - [email protected] / [email protected] / [email protected] **OM NAMAH SHIVAYA** Holy Mt. KAILASH YATRA WITH NANDI & INNER PARIKRAMA (KORRA): HOLY MT KAILASH AND MANSAROVAR LAKE- AN INTRODUCTION: Holy Mt Kailash and Mansarowar Lake, center of creation & the Universe are as old as the creation. Thousands of Sages, Ordinary Mortals, Philosophers and even Gods had submerged in the blissful trance at the very sight of this divine grandeur. It is the MERU, SUMERU, SUSHUMNA, HEMADRI (Golden Mountain), RATNASANU (Jewel Peak), KARNIKACHALA (Lotus Mountain), AMARADRI, DEVA PARVATHA (Summit of Gods), GANAPARVATHA, AJATADRI (Silver Mountain). Regarded as SWAYAMBHU, the self-created one, everythingis said to emanate from here and finally returns here. Mind is the knot tying consciousness and matter-that is set free here. Famously known to be an abode of LORD SHIVA and his divine consort PARVATI, Mt. Kailash expounds the philosophy of PURUSHA and PRAKRITI-SHIVA and SHAKTI. The radiant SILVERLY summit is the throne of TRUTH, WISDOM and BLISS-SACHIDANANDAM. The primordial sound AUM (NADABINDU) from the tinkling anklets of LALITA PRAKRITI created the visible patterns of the universe and the vibrations (DVANI) from the feet of Lord Shiva (NATARAJA) weaved the essence of ATMAN, the ultimate truth. Mt. Kailash is considered to be the centre of Hindu philosophy and civilization. Kalpa Viruksha tree is supposed to adorn the slopes. South face is described as Sapphire, east as crystal, west as Ruby and north as Gold. -

Parikrama Booklet 2020

All glories to Çré Guru and Gauräìga Çré Navadvépa Maëòala Parikrama Gauräbda 534 (2020) 30th anniversary celebration Itinerary & General Information ISKCON International Society for Kåñëa Consciousness Sri Mayapur Chandrodaya Mandir Founder-Äcärya: His Divine Grace A.C. Bhaktivedänta Swämi Prabhupäda 2 śrī-rādhāyāḥ praṇaya-mahimā kīdṛśo vānayaivā- svādyo yenādbhuta-madhurimā kīdṛśo vā madīyaḥ saukhyaṁ cāsyā mad-anubhavataḥ kīdṛśaṁ veti lobhāt tad-bhāvāḍhyaḥ samajani śacī-garbha-sindhau harīnduḥ Desiring to understand the glory of Rādhārāṇī’s love, the wonderful qualities in Him that She alone relishes through Her love, and the happiness She feels when She realizes the sweetness of His love, the Supreme Lord Hari, richly endowed with Her emotions, appeared from the womb of Śrīmatī Śacī-devī, as the moon appeared from the ocean. Sri Caitanya Caritamrta, 1.1.6 by Krsnadasa Kaviraj Goswami WELCOME TO SRI NAVADVIPA MANDALA PARIKRAMA 2020! 30TH ANNIVERSARY CELEBRATION FESTIVAL HARE KRSNA! JAY GAUR! JAY NITAI! ALL GLORIES TO SRILA PRABHUPADA AND HIS FOLLOWERS! DEAR DEVOTEES, WELCOME HOME! ALL THE MAYAPUR DEVOTEES ARE VERY HAPPY TO SERVE YOU IN THIS WONDERFUL CELEBRATION OF 30 YEARS OF JOY, WHERE WE DO WHAT WE LOVE, JUST WALKING IN THE HOLY DHAM, IN THE ASSOCIATION OF LOVELY PEOPLE, CHANTING HARE KRSNA AND HAVING BHAGAVAT PRASADA! JAY HO! IN THE YEAR 1990 A VERY IMPORTANT CHANGE HAPPENED TO THE PARIKRAMA. ALL THE PILGRIMS HAD THE OPPORTUNITY TO STAY OVERNIGHT INSTEAD OF COMING BACK TO ISKCON MAYAPUR COM- PLEX IN THE END OF THE DAY. IT MAKES -

Karnali Excursions, Nepal

1 Karnali Excursions Kailash Yatra 2020 1 ç Om Namah Shivaya Karnali Excursions, Nepal Kailash - Mansarovar Yatra & Other Himalayan Pilgrimages 2020 Join with us for the journey of a lifetime to experience Satyam, Shivam and Sundaram www.karnaliexcursions.com Karnali Excursions Kailash Yatra 2020 2 Table of Contents: SN. Contents Page No. 1. About Kailash & Our Services 3 2. Kailash-Mansarovar & Other Yatra Maps 4 3. Fixed Departure Dates of Kailash-Mansarovar Yatra & Other Pilgrimages 5 - 6 4. Kailash-Mansarovar Yatra only 7 5. Kailash-Mansarovar Yatra with Muktinath Darshan 8 6. Kailash-Mansarovar with Muktinath-Janakpur Dham-Valmiki Ashram-Devghat-Lumbini 9 7. About Muktinath, Damodar Kunda, Janakpur Dham, Devghat, Valmiki Ashram, Lumbini and Chitwan National Park 10 - 13 8. Kailash-Mansarovar with Chardham Yatra 14 9. Kailash-Mansarovar with Shree Amarnath Yatra 15 10. Shree Amarnath Yatra only 16 - 17 11. Chardham Yatra only 18 - 19 12. Jyotirling Darshan Yatra 20 - 21 13. Narmad Parikrama-Arunachal Hill-Pancha Mahabhoot Yatra 22 14. Swaminarayan Trail Tour 23 - 24 15. World-wide Contact Details 26 2 Karnali Excursions Kailash Yatra 2020 3 Om Namah Shivaya! “As the dew is dried up by the morning sun, so are the sins of human beings by the sight of Mt. Kailash and Lake Manasarovar” - Skanda Purana” Holy Mount Kailash is believed as an important pilgrimage destination as well as a power point, where it is possible to gain inspiration and energy to transform oneself from this physical to higher spiritual level. The custom of circumambulating Mount Kailash is believed to purify the soul and cultivate in each visiting pilgrim the ability to experience the divinity. -

Why I Became a Hindu

Why I became a Hindu Parama Karuna Devi published by Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Copyright © 2018 Parama Karuna Devi All rights reserved Title ID: 8916295 ISBN-13: 978-1724611147 ISBN-10: 1724611143 published by: Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Website: www.jagannathavallabha.com Anyone wishing to submit questions, observations, objections or further information, useful in improving the contents of this book, is welcome to contact the author: E-mail: [email protected] phone: +91 (India) 94373 00906 Please note: direct contact data such as email and phone numbers may change due to events of force majeure, so please keep an eye on the updated information on the website. Table of contents Preface 7 My work 9 My experience 12 Why Hinduism is better 18 Fundamental teachings of Hinduism 21 A definition of Hinduism 29 The problem of castes 31 The importance of Bhakti 34 The need for a Guru 39 Can someone become a Hindu? 43 Historical examples 45 Hinduism in the world 52 Conversions in modern times 56 Individuals who embraced Hindu beliefs 61 Hindu revival 68 Dayananda Saraswati and Arya Samaj 73 Shraddhananda Swami 75 Sarla Bedi 75 Pandurang Shastri Athavale 75 Chattampi Swamikal 76 Narayana Guru 77 Navajyothi Sree Karunakara Guru 78 Swami Bhoomananda Tirtha 79 Ramakrishna Paramahamsa 79 Sarada Devi 80 Golap Ma 81 Rama Tirtha Swami 81 Niranjanananda Swami 81 Vireshwarananda Swami 82 Rudrananda Swami 82 Swahananda Swami 82 Narayanananda Swami 83 Vivekananda Swami and Ramakrishna Math 83 Sister Nivedita -

Ayodhya: the Backbone of Hindu Ideology

International Journal of Civil Engineering and Technology (IJCIET) Volume 9, Issue 12, December 2018, pp. 736-743, Article ID: IJCIET_09_12_078 Available online at http://iaeme.com/Home/issue/IJCIET?Volume=9&Issue=12 ISSN Print: 0976-6308 and ISSN Online: 0976-6316 © IAEME Publication Scopus Indexed AYODHYA: THE BACKBONE OF HINDU IDEOLOGY Ar. Madhavendra Pratap Singh Department of Architecture, Amity University, Lucknow Campus, India, Dr. Vandana Sehgal Faculty of Architecture, Dr. APJ Abdul Kalam Technical University, Lucknow Campus, India, ABSTRACT Ayodhya is known as one of the ancient cities in India and the birthplace of Lord Ram. The city is considered to be a religious Centre for Hinduism and hence an attraction for millions of devotees across the world. The city can be called as a Vatican of India in terms of a religious centre where thousands of years old teaching and preaches are being practised on a daily basis not only by the Sadhus but by the locals living within the city. Situated on the bank of Saryu river, like all the early civilizations in India; the city has provided an ultimate source of water supply to the nearby settlements to flourish. According to the Hindu mythology in Ramayana, the city was founded by Manu (the first man in Veda). Lord Ram who was believed to be the seventh incarnation of Lord Vishnu (approx. 900000 years) was born in the city and became the most celebrated king of the Surya Dynasty and under his regime, the city became the capital of Hinduism [5]. With the rise of the Buddhism in the sixth and seventh century the city has lost its character of a holy city in Hinduism but later the city again became the spiritual centre when it was rediscovered by Vikramaditya. -

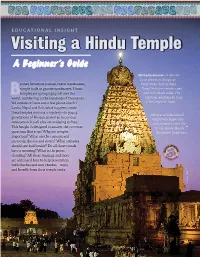

Visiting a Hindu Temple

EDUCATIONAL INSIGHT Visiting a Hindu Temple A Beginner’s Guide Brihadeeswarar: A massive stone temple in Thanjavur, e they luxurious palaces, rustic warehouses, Tamil Nadu, built by Raja simple halls or granite sanctuaries, Hindu Raja Chola ten centuries ago B temples are springing up all over the and still vibrant today. The world, numbering in the hundreds of thousands. capstone, weighing 80 tons, Yet outside of India and a few places like Sri is the largest in India. Lanka, Nepal and Bali, what happens inside these temples remains a mystery—to young This special Educational generations of Hindus as well as to curious Insight was inspired by newcomers. It’s all a bit intimidating at first. and produced expressly This Insight is designed to answer the common for the Hindu Mandir questions that arise: Why are temples Executives’ Conference important? What are the customs and protocols, the dos and don’ts? What attitudes should one hold inside? Do all those rituals ATI O C N U A D have a meaning? What is the priest L E chanting? All these musings and more I N S S T are addressed here to help newcomers— I G H both Hindus and non-Hindus—enjoy and benefit from their temple visits. dinodia.com Quick Start… Dress modestly, no shorts or short skirts. Remove shoes before entering. Be respectful of God and the Gods. Bring your problems, prayers or sorrows but leave food and improper manners outside. Do not enter the shrines without invitation or sit with your feet pointing toward the Deities or another person. -

Step by Step Explanation of the Full Wedding Ceremony

Step by Step Explanation of the Full Wedding Ceremony The marriage is the biggest, most elaborate, magnificent, spectacular and impressive of all the life cycle rituals in a Hindu's life. Of course what's given below is just a simple format. Many areas of India perform the wedding with slight variations. I am enlightening you on the most important parts as explanation of each part of the wedding will make this article rather voluminous. This is part 2 of the marriage rites with part one dealing with the preliminaries of the wedding. The marriage ceremony may be divided into three parts. Summary: Part One Reception of the bridegroom and his parents by the bride's parents at the entrance gate of the hall. The reception of the bridegroom on the stage and giving of presents by bride's father. Bride's parents give their daughter away to the bridegroom. Part Two Marriage ceremony proper Sacred Fire Ceremony Solemn vows and joining hands Stone-stepping ceremony Fried-rice (popcorn) offered as oblations into the sacred Fire. Marriage nuptial knot Walking around the Sacred Fire taking holy vows. The ceremony of Seven steps Part Three Benediction (blessings) My humble advise if the wedding is taking place at 11h00 sharp (Do note - this is an example time) the bride and groom should be at the hall around an hour before the wedding proper starts... The Samdhimilan suggested time should be around 10h20. The Parchan Puja suggested time should be around 10h25. The Dwaar Puja suggested time should be around 10h40. The Groom who walks in with his entourage should walk in around 10h50.