Shoreline Technical Assistance for Homeowners in the Puget Sound Region Potential Service Delivery Models and Lessons Learned from Existing Programs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Snohomish Estuary Wetland Integration Plan

Snohomish Estuary Wetland Integration Plan April 1997 City of Everett Environmental Protection Agency Puget Sound Water Quality Authority Washington State Department of Ecology Snohomish Estuary Wetlands Integration Plan April 1997 Prepared by: City of Everett Department of Planning and Community Development Paul Roberts, Director Project Team City of Everett Department of Planning and Community Development Stephen Stanley, Project Manager Roland Behee, Geographic Information System Analyst Becky Herbig, Wildlife Biologist Dave Koenig, Manager, Long Range Planning and Community Development Bob Landles, Manager, Land Use Planning Jan Meston, Plan Production Washington State Department of Ecology Tom Hruby, Wetland Ecologist Rick Huey, Environmental Scientist Joanne Polayes-Wien, Environmental Scientist Gail Colburn, Environmental Scientist Environmental Protection Agency, Region 10 Duane Karna, Fisheries Biologist Linda Storm, Environmental Protection Specialist Funded by EPA Grant Agreement No. G9400112 Between the Washington State Department of Ecology and the City of Everett EPA Grant Agreement No. 05/94/PSEPA Between Department of Ecology and Puget Sound Water Quality Authority Cover Photo: South Spencer Island - Joanne Polayes Wien Acknowledgments The development of the Snohomish Estuary Wetland Integration Plan would not have been possible without an unusual level of support and cooperation between resource agencies and local governments. Due to the foresight of many individuals, this process became a partnership in which jurisdictional politics were set aside so that true land use planning based on the ecosystem rather than political boundaries could take place. We are grateful to the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), Department of Ecology (DOE) and Puget Sound Water Quality Authority for funding this planning effort, and to Linda Storm of the EPA and Lynn Beaton (formerly of DOE) for their guidance and encouragement during the grant application process and development of the Wetland Integration Plan. -

South Tacoma Way, Circa 1913, Photo Courtesy of the Tacoma Public Library, Amzie D

The west side of the 5200 block of South Tacoma Way, circa 1913, photo courtesy of the Tacoma Public Library, Amzie D. Browning Collection 158 2 011 Historic South Tacoma Way South Tacoma Way Business District In early 2011, Historic Tacoma reached out to the 60+ member South Tacoma Business District Association as part of its new neighborhood initiative. The area is home to one of the city’s most intact historic commercial business districts. A new commuter rail station is due to open in 2012, business owners are interested in S 52nd St taking advantage of City loan and grant programs for façade improvements, and Historic Tacoma sees S Washington St great opportunities in partnering with the district. S Puget Sound Ave The goals of the South Tacoma project are to identify and assess historic structures and then to partner with business owners and the City of Tacoma to conserve and revitalize the historic core of the South Tacoma Business District. The 2011 work plan includes: • conducting a detailed inventory of approximately 50 commercial structures in the historic center of the district • identification of significant and endangered South Way Tacoma properties in the district • development of action plans for endangered properties • production of a “historic preservation resource guide for community leaders” which can be S 54th St used by community groups across the City • ½ day design workshop for commercial property owners • production & distribution of a South Tacoma Business District tour guide and map • nominations to the Tacoma Register of Historic Places as requested by property owners • summer walking tour of the district Acknowledgements Project funding provided by Historic Tacoma, the South Tacoma Business District Association, the South Tacoma Neighborhood Council, the University of Washington-Tacoma, and Jim and Karen Rich. -

South Puget Sound Community College Year Three Mid-Cycle Evaluation

South Puget Sound Community College Year Three Mid-Cycle Evaluation Dr. Timothy Stokes President September, 2014 Table of Contents Report on Year One Recommendation ......................................................................................................... 1 Mission .......................................................................................................................................................... 1 Part I .............................................................................................................................................................. 1 Mission Fulfillment .................................................................................................................................... 1 Operational Planning ................................................................................................................................ 2 Core Themes, Objectives and Indicators .................................................................................................. 3 Part II ............................................................................................................................................................. 4 Rationale for Indicators of Achievement .................................................................................................. 5 Increase Student Retention (Objective 1.A) ......................................................................................... 5 Support Student Completion (Objective 1.B) ...................................................................................... -

Economic Development Goals

six ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT GOALS GOAL EC–1 Diversify and expand Tacoma’s economic base to create a robust economy that offers Tacomans a wide range of employment opportunities, goods and services. GOAL EC–2 Increase access to employment opportunities in Tacoma and equip Tacomans with the education and skills needed to attain high- quality, living wage jobs. GOAL EC–3 Cultivate a business culture that allows existing establishments to grow in place, draws new firms to Tacoma and encourages more homegrown enterprises. GOAL EC–4 Foster a positive business environment within the City and proactively invest in transportation, infrastructure and utilities to grow Tacoma’s economic base in target areas. GOAL EC–5 Create a city brand and image that supports economic growth and leverages existing cultural, community and economic assets. GOAL EC–6 Create robust, thriving employment centers and strengthen and protect Tacoma’s role as a regional center for industry and commerce. 6-2 SIX Book I: Goals + Policies 1 Introduction + Vision ECONOMIC 2 Urban Form 3 Design + Development 4 Environment + Watershed Health DEVELOPMENT 5 Housing 6 Economic Development 7 Transportation 8 Parks + Recreation 9 Public Facilities + Services 10 Container Port 11 Engagement, Administration + Implementation 12 Downtown Book II: Implementation Programs + Strategies 1 Shoreline Master Program WHAT IS THIS CHAPTER ABOUT? 2 Capital Facilities Program 3 Downtown Regional Growth The goals and policies in this chapter convey the City’s intent to: Center Plans 4 Historic Preservation Plan • Diversify and expand Tacoma’s economic base to create a robust economy that offers Tacomans a wide range of employment opportunities, goods and services; leverage Tacoma’s industry sector strengths such as medical, educational, and maritime operations and assets such as the Port of Tacoma, Joint Base Lewis McChord, streamlined permitting in downtown and excellent quality of life to position Tacoma as a leader and innovator in the local, regional and state economy. -

Tacoma‐Pierce County Board of Health

Tacoma‐Pierce County Board of Health Regular Meeting Agenda 3629 South D Street, Tacoma, WA 98418 January 20, 2021 Board of Health Clerk, (253) 798‐2899 3 ‐ 5 p.m. Board Members Remote Attendance Only Keith Blocker Dial in: 253 215 8782 Marty Campbell Meeting ID: 992 6138 9468 Bruce Dammeier William Hirota, MD Passcode: 575390 Patricia Johnson Dave Morell Catherine Ushka I. CALL TO ORDER Derek Young II. ROLL CALL III. ELECTION OF BOARD OF HEALTH (BOH) OFFICERS Motion for 2021 BOH Chair Motion for 2021 BOH Vice Chair IV. COMMENTS BY THE PUBLIC The Board will consider written and oral public comments. Submit written comments any time prior to when a Board of Health meeting adjourns at [email protected]. Written comments we receive prior to noon on the date of a Board of Health meeting will go to Board members before the meeting. For the duration of the declared public health emergency, make oral comments when you join the meeting by phone with the number, meeting ID, and passcode at the top of the agenda. Press *9 to raise your hand and signal you wish to make a comment. You will be announced by your name or the last four digits of your phone number. Comments unrelated to specific agenda items have a two‐minute limit per person. The Chair has the authority to change the time limits as deemed necessary. All written and oral comments will become part of the meeting record. V. COVID‐19: Update [Anthony L‐T Chen, Director of Health] [Nigel Turner, Incident Commander] [Kayla Scrivner, Public Health Nurse] VI. -

Development of a Hydrodynamic Model of Puget Sound and Northwest Straits

PNNL-17161 Prepared for the U.S. Department of Energy under Contract DE-AC05-76RL01830 Development of a Hydrodynamic Model of Puget Sound and Northwest Straits Z Yang TP Khangaonkar December 2007 DISCLAIMER This report was prepared as an account of work sponsored by an agency of the United States Government. Neither the United States Government nor any agency thereof, nor Battelle Memorial Institute, nor any of their employees, makes any warranty, express or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed, or represents that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the United States Government or any agency thereof, or Battelle Memorial Institute. The views and opinions of authors expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the United States Government or any agency thereof. PACIFIC NORTHWEST NATIONAL LABORATORY operated by BATTELLE for the UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF ENERGY under Contract DE-AC05-76RL01830 Printed in the United States of America Available to DOE and DOE contractors from the Office of Scientific and Technical Information, P.O. Box 62, Oak Ridge, TN 37831-0062; ph: (865) 576-8401 fax: (865) 576-5728 email: [email protected] Available to the public from the National Technical Information Service, U.S. Department of Commerce, 5285 Port Royal Rd., Springfield, VA 22161 ph: (800) 553-6847 fax: (703) 605-6900 email: [email protected] online ordering: http://www.ntis.gov/ordering.htm This document was printed on recycled paper. -

Ground-Water Flooding in Glacial Terrain of Southern Puget Sound

science fora changing world Ground-Water Flooding in Glacial Terrain of Southern Puget Sound, Washington glacial lakes, and diverting drainage landforms and, in some places, eroded southward to the Chehalis River and then away sediments deposited during the west to the Pacific Ocean to create exten glacial advance. Coarse sediment, known sive outwash plains6' 7' 10. At its maximum as the Steiiacoom Gravel, was also extent, the glacier stretched from the deposited on the upland by water flowing Cascade Range to the Olympic Mountains through the intersecting channels and and extended south as far as Tenino, braided streams that further conveyed the Wash., in Thurston County, occupying all water away from the proglacial lake.2- 13 of the lowland area and lower mountain This gravel deposit is consistently coarse valleys. The glacier reached altitudes up over the central Pierce County upland to 4,000 feet along the mountain front10; area. Stones in the Steiiacoom Gravel are 6,000 feet near the present day United predominantly 1 inch in size and most do States-Canada border; 3,000 feet near not exceed 3 inches. 13 The thickness of Seattle; 2,200 feet near Tacoma; and less the gravel is generally 20 feet or less with than 1.000 feet near Olympia. 1' 4- 10 a maximum that rarely exceeds 60 feet. The resulting landscape is characterized T^\ ue to a global warming trend, the by many shallow, elongated depressions Figure 1. Proglacial Lake Puyattup and J ^Vashon Glacier began retreating and ice-contact depressions (kettles). The successive Lake Spillways (modified from its terminus about 17.000 years ago.7 larger and deeper depressions are occu from Thorson, 1979). -

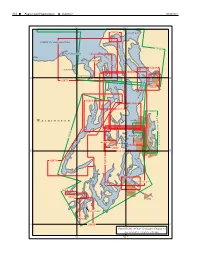

Kitsap County Watershed Location Map Washington State Seems to Have an Abundance of Water

KITSAP COUNTY INITIAL BASIN ASSESSMENT October 1997 With the multitudes of lakes, streams, and rivers, Kitsap County Watershed Location Map Washington State seems to have an abundance of water. The demand for water resources, however, has steadily increased each year, while the water supply has stayed the same, or in some cases, appears to have declined. This increased demand for limited water resources has made approving new water uses complex and controversial. To expedite decisions about pending water rights, it is vital to accurately assess the quality and quantity of our surface and ground water. The Washington State Department of Ecology (Ecology) recognizes that water right decisions must be based on accurate scientific information. Ecology is working with consultants and local governments to conduct special studies called Initial What do we know about the Kitsap County Watershed or Basin Assessments throughout the Basin? State. The assessments describe existing water rights, streamflows, precipitation, geology, hydrology, Kitsap County encompasses almost 400 square miles and water quality, fisheries resources, and land use occupies a peninsula and several islands in Puget Sound. patterns. It is bounded on the east and north by Puget Sound and The assessments evaluate existing data on water which Admiralty Inlet, and on the west by Hood Canal. The will assist Ecology to make decisions about pending County is adjoined by Pierce and Mason Counties on the water right applications. The assessments do not affect south, Jefferson County -

Chapter 13 -- Puget Sound, Washington

514 Puget Sound, Washington Volume 7 WK50/2011 123° 122°30' 18428 SKAGIT BAY STRAIT OF JUAN DE FUCA S A R A T O 18423 G A D A M DUNGENESS BAY I P 18464 R A A L S T S Y A G Port Townsend I E N L E T 18443 SEQUIM BAY 18473 DISCOVERY BAY 48° 48° 18471 D Everett N U O S 18444 N O I S S E S S O P 18458 18446 Y 18477 A 18447 B B L O A B K A Seattle W E D W A S H I N ELLIOTT BAY G 18445 T O L Bremerton Port Orchard N A N 18450 A 18452 C 47° 47° 30' 18449 30' D O O E A H S 18476 T P 18474 A S S A G E T E L N 18453 I E S C COMMENCEMENT BAY A A C R R I N L E Shelton T Tacoma 18457 Puyallup BUDD INLET Olympia 47° 18456 47° General Index of Chart Coverage in Chapter 13 (see catalog for complete coverage) 123° 122°30' WK50/2011 Chapter 13 Puget Sound, Washington 515 Puget Sound, Washington (1) This chapter describes Puget Sound and its nu- (6) Other services offered by the Marine Exchange in- merous inlets, bays, and passages, and the waters of clude a daily newsletter about future marine traffic in Hood Canal, Lake Union, and Lake Washington. Also the Puget Sound area, communication services, and a discussed are the ports of Seattle, Tacoma, Everett, and variety of coordinative and statistical information. -

South Puget Sound Prairies the Nature Conservancy of Washington 2007 Conservation Vision

Conservation Action Planning Report for the SOUTH PUGET SOUND PRAIRIES The Nature Conservancy of Washington 2007 CONSERVATION VISION Successful conservation of the South Puget Sound Prairies will entail elements of protection, active land management and restoration, and integration of the full suite of partners working within the Willamette Valley - Puget Trough - Georgia Basin Ecoregion. The portfolio of protected conservation sites will contain a mosaic of habitats that support the full-range of prairie and oak woodland species. This portfolio will be a total of 20 protected sites, including at least six core areas. The core areas of the portfolio consist of protected sites embedded within a mosaic of land-use that complements prairie conservation and the protected conservation sites. The portfolio will take advantage of the wide-range of microclimates in the South Puget Sound, aimed at providing resiliency to the potential effects of climate change. The South Puget Sound will contribute to the conservation of rare species by promoting and implementing recovery actions throughout their historic range. Active management of the prairie maximizes the contribution to conservation of all portfolio sites. These management actions are coordinated and integrated across a range of partners and landowners. This integration ensures that information transfer is exemplary, that organizations are linked formally and informally and that sufficient resources are generated for all partners. The South Puget Sound Prairies will be a primary source for prairie-specific science and restoration techniques. It will similarly be a source concerning the science and conservation for fragmented natural systems. Prairie conservation in the South Puget Sound will be supported by a community that is actively engaged through a vigorous volunteer program and supports the financial and policy issues that affect prairies. -

PUGET SOUND PLAZA PUGET SOUND PLAZA 1325 Fourth Avenue | Seattle, Washington 98101

PUGET SOUND PLAZA PUGET SOUND PLAZA 1325 Fourth Avenue | Seattle, Washington 98101 VIEW THE NEW ONLINE TOUR BOOK HERE BUILDING FACTS BUILDING AMENITIES ON-SITE RETAIL » Lobby » Total Building Size ...................279,586 RSF » Union Deli » Conference room facility » Number of Floors ....................21 » Key Bank » Shower » Average Floor Plate ................13,800 RSF » Seattle Vision Care » 306 parking stalls » Year Built .....................................1960 » Skyline Hair Design » EV charging system » Parking Ratio .............................1 / 1,800 SF » Northwest Pendleton » Bike storage » LEED Gold Certified » UW - Husky Central » Fitwel Viral Response Certified » Kudedon Noodles Click the play buttons for virtual tours Damon McCartney David Greenwood (206) 838-7633 (206) 838-7635 [email protected] [email protected] Fairview Ave N Aloha St Valley St Roy St E Roy St Mercer St Yale Ave N Ave Yale E Mercer St Republican St Republican St Bellevue E Ave Westlake Ave N Ave Westlake Fairview Ave N Ave Fairview Dexter N Ave 9th Ave N 9th Ave Harrison St Thomas St John St Denny Way Westlake Ave 6th Ave Stewart St Battery St WALK SCORE Bell St PUGET SOUND PLAZA Blanchard St 99AVG ACROSS ALL 1325 Fourth Avenue | Seattle, Washington 98101 Olive Way METROPOLITAN TRACT BLDGS Lenora St Pine St 1 Virginia St RAINIER 6th Ave TOWER 1 CBD 7 PUGET SOUND 1 5th Ave PLAZA Pike St Lifestyle 6 1. Regal Cinemas 4th Ave 1 2 2. Westlake Park 5 2 1 3. Home Street Bank 3 9 Union St SKINNER 4. 5th Avenue Theater 2 2nd Ave BUILDING 5. U.S. Post Office 7 1 6. Key Bank 4 7 3 6 4 7. -

Lime Kiln Point State Park (San Juan Island)

Ranald MacDonald’s Grave Your guide to state parks in the Auto-accessible parks Auto-accessible parks Lime Kiln Point State Park Moran State Park Spencer Spit State Park Obstruction Pass State Park Welcome (San Juan Island) (Orcas Island) (Lopez Island) (Orcas Island) San Juan The San Juan archipelago north of Puget At Lime Kiln Point State Park, the loud neighbors Pass through the welcome arch at Moran State Spencer Spit on Lopez Island provides dramatic Obstruction Pass State Park is one of the few Sound is like no other place on earth. The cluster gear up for a party that runs from spring into Park, and time begins to slow. You’ll find yourself views of Decatur and Blakely islands and Mount public beaches on famed Orcas Island. of 400 islands and rocks in the Salish Sea is a fall. Those would be the spouting Orcas, fin- in a Northwest island frame of mind, free to relax, Constitution on Orcas Island, and it features a Though most people flock to its bigger world unto itself. It is a world where people are slapping gray whales, barking sea lions and breathe and head into the vast, varied terrain. rare sand spit enclosed by a salt-chuck lagoon. neighbor, Moran State Park, this property’s friendly and hearty, where the land smells like splashing porpoises. Hike, cycle or drive to the summit of Mount The effect is a driftwood-scattered beach on quiet beauty is unsurpassed. Clear waters lap at the sea, and wind, art and history are celebrated. Constitution for expansive views of the San Juan one side of the spit and a spongy marsh on the pebbly beaches, and madrone trees cling to Obstruction Pass Islands For island dwellers and visitors, the pace of life other.