Brighton and Hove Case Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Derby and Nottingham Transforming Cities Fund Tranche 2 Strategic Outline Business Case November 2019

Derby and Nottingham Transforming Cities Fund Tranche 2 Strategic Outline Business Case November 2019 Derby and Nottingham Transforming Cities Fund Tranche 2 Strategic Outline Business Case November 2019 Produced by: With support from: Contact: Chris Carter Head of Transport Strategy Nottingham City Council 4th Floor, Loxley House Station Street Nottingham NG2 3NG 0115 876 3940 [email protected] Derby & Nottingham - TCF Tranche 2 – Strategic Outline Business Case Document Control Sheet Ver. Project Folder Description Prep. Rev. App. Date V1-0 F:\2926\Project Files Final Draft MD, NT CC, VB 28/11/19 GT, LM, IS V0-2 F:\2926\Project Files Draft (ii) MD, NT CC, VB 25/11/19 GT, LM, IS V0-1 F:\2926\Project Files Draft (i) MD, NT NT 11/11/19 GT, LM, IS i Derby & Nottingham - TCF Tranche 2 – Strategic Outline Business Case Table of Contents 1. Introduction .............................................................................................................................. 1 Bid overview ................................................................................................................................................... 1 Structure of the remainder of this document ................................................................................... 2 2. Strategic Case: The Local Context ................................................................................... 3 Key statistics and background ............................................................................................................... -

Slough Children's Social Care Services

— Slough Children’s Social Care Services Report to Department for Education June 2014 OPM SLOUGH CHILDREN’S SOCIAL CARE SERVICES Client Department for Education Title Slough Children’s Social Care Services Date Modified 10 June 2014 Status Final OPM Project Code 9853 Author Hilary Thompson with Deborah Rozansky, Dave Hill and Helen Lincoln Quality Assurance by Hilary Thompson Main point of contact Hilary Thompson Telephone 020 7239 7800 Email [email protected] If you would like a large text version of this document, please contact us. OPM 252b Gray’s Inn Road 0845 055 3900 London www.opm.co.uk WC1X 8XG [email protected] 2 OPM SLOUGH CHILDREN’S SOCIAL CARE SERVICES Table of Contents Introduction 4 Terms of reference 4 Process 5 Background 6 Our analysis 10 Scale and funding 10 Current structures and processes 12 People and culture 14 Capacity for improvement 17 Transition issues 18 Criteria and options 19 Criteria 22 Options 24 Recommendations 26 Scope 26 Organisational and governance arrangements 27 Transition 31 Duration of arrangements 32 Appendix 1 – Local contributors 33 Appendix 2 – Documents 35 Appendix 3 – Good governance standard 37 Appendix 4 – A ‘classic’ model of a children’s service 39 Appendix 5 – Proposals from SBC 40 3 Introduction Following the Ofsted inspection of children’s services in Slough in November and early December 2013, the Department for Education (DfE) appointed a review team to look at arrangements for the future. The team was led by Hilary Thompson, working with OPM colleague Deborah Rozansky and with Dave Hill, Executive Director of People Commissioning (and statutory DCS) at Essex County Council, and his colleague Helen Lincoln, Executive Director for Family Operations. -

Sexual Health Introduction This Constitutes the Full Section on Sexual Health for the Adults’ JSNA 2016

For feedback, please contact [email protected] Last updated 4-Apr-16 Review date 30-Apr-17 Sexual Health Introduction This constitutes the full section on Sexual Health for the Adults’ JSNA 2016. ‘Sexual health is a state of physical, mental and social well-being in relation to sexuality. It requires a positive and respectful approach to sexuality and sexual relationships, as well as the possibility of having pleasurable and safe sexual experiences, free of coercion, discrimination and violence.’1 Who’s at risk and why? According to the National Survey of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles Surveys (Natsal)2,3 sexual health behaviour of the population of England has changed since the survey was first undertaken in 1991. The 2011 Natsal survey demonstrated an increase in the: number of sexual partners over a person’s lifetime, particularly for women, where this has increased from 3.7 (1991) to 7.7 (2011) sexual repertoire of heterosexual partners, particularly with oral and anal sexual intercourse All sexually active individuals of all ages are at risk of sexually transmitted infections (STIs), including HIV, and unplanned pregnancies (in the fertile years). However, the risks are not equally distributed amongst the population, with certain groups being at greater risk. Poor sexual health may also be associated with other poor health outcomes. Those at highest risk of poor sexual health are often from specific population groups, with varying needs which include: Men who have sex with men (MSM) Young people who are more likely to become re-infected with STIs Some black and ethnic minority groups Sex workers Victims of sexual and domestic abuse Other marginalised or vulnerable groups, including prisoners Nationally, there is a correlation between STIs and deprivation. -

BERKSHIRE PROSPECTUS AMBITION, COLLABORATION and GROWTH Thames Valley Berkshire LEP Berkshire Prospectus Local Authorities As Well As Other Key Stakeholders

BERKSHIRE PROSPECTUS AMBITION, COLLABORATION AND GROWTH 02 THE BERKSHIRE Berkshire Prospectus Berkshire PROSPECTUS THE OPPORTUNITIES IN THIS PROSPECTUS It is no coincidence that this prospectus for Berkshire has been released in tandem with the Thames Valley Berkshire Local Enterprise Partnership (LEP) Recovery and REPRESENT A CHANCE Renewal Plan. The two documents sit alongside each other, evidencing the formidable collaborative nature of how TO RESET POST COVID the LEP is working in partnership with the six Berkshire Local Authorities as well as other key stakeholders. AND MAKE BERKSHIRE This prospectus clearly identifies several key schemes and projects which, when delivered, will greatly enhance Berkshire’s appeal as a place to live and EVEN BETTER work in the years ahead. The projects highlighted in this prospectus represent unique opportunities for new investment that will appeal to a wide range of partners, locally, regionally and nationally. The LEP and Local Authorities will work alongside private and public sector colleagues to facilitate the development and successful delivery of these great opportunities. COLLABORATIVE WORKING We should highlight the constructive partnership between the Local Authorities and the LEP, who together have forged a great working relationship with One Public Estate (OPE). Established in 2013, OPE now works nationally with more than 300 councils.These projects are transforming local communities and public services right across the country. They provide technical support and funding to councils to deliver ambitious property and place-focused programmes in collaboration with central government and other public sector partners. Thames Valley Berkshire LEP Berkshire Thames Valley 03 As highlighted in the Recovery and Renewal Plan, Thames Valley Berkshire is more than the sum of its parts. -

76, Eldred Avenue, Brighton, BN1 5EH 76, Eldred Avenue, Brighton, BN1 5EH Guide Price £500,000 - Freehold

76, Eldred Avenue, Brighton, BN1 5EH 76, Eldred Avenue, Brighton, BN1 5EH Guide Price £500,000 - Freehold • Stylish semi detached house • Dual aspect living room with leafy views • White modern kitchen breakfast room • Three good size first floor bedrooms • Modern first floor bathroom/WC • Shared driveway and garage • Large rear garden with two patio spaces • Delightful garden room & deck • Mature architectural plants • Viewing highly recommended GUIDE PRICE - £500,000-£525,000 Leafy Green Westdene. This stylish light filled home has lovely views from all the principle rooms which feature neutral decoration and wooden flooring. WE LOVE the large rear garden with mature architectural plants, two patio spaces, ideal for entertaining and an amazing garden room with deck. The home features a large dual aspect living room with full height patio doors overlooking the rear Brighton is something very special, a lively, cultured, sophisticated seaside town within a stones throw garden and patio. There is ample space for sofa's and a dining table of the South Downs. Eldred Avenue is ideally situated to take advantage of the express transport and chairs. The spacious kitchen is equipped with white modern links to both Brighton and London along with nearby amenities in Patcham Old Village and Preston units, wood block work tops and a sit up breakfast bar. Lets not forget Park. Schools catering for all ages can be easily accessed. the range style cooker and space for an american style fridge/freezer. On the first floor there are three good size bedrooms and a modern bathroom/WC with a white suite. -

Neighbourhoods in England Rated E for Green Space, Friends of The

Neighbourhoods in England rated E for Green Space, Friends of the Earth, September 2020 Neighbourhood_Name Local_authority Marsh Barn & Widewater Adur Wick & Toddington Arun Littlehampton West and River Arun Bognor Regis Central Arun Kirkby Central Ashfield Washford & Stanhope Ashford Becontree Heath Barking and Dagenham Becontree West Barking and Dagenham Barking Central Barking and Dagenham Goresbrook & Scrattons Farm Barking and Dagenham Creekmouth & Barking Riverside Barking and Dagenham Gascoigne Estate & Roding Riverside Barking and Dagenham Becontree North Barking and Dagenham New Barnet West Barnet Woodside Park Barnet Edgware Central Barnet North Finchley Barnet Colney Hatch Barnet Grahame Park Barnet East Finchley Barnet Colindale Barnet Hendon Central Barnet Golders Green North Barnet Brent Cross & Staples Corner Barnet Cudworth Village Barnsley Abbotsmead & Salthouse Barrow-in-Furness Barrow Central Barrow-in-Furness Basildon Central & Pipps Hill Basildon Laindon Central Basildon Eversley Basildon Barstable Basildon Popley Basingstoke and Deane Winklebury & Rooksdown Basingstoke and Deane Oldfield Park West Bath and North East Somerset Odd Down Bath and North East Somerset Harpur Bedford Castle & Kingsway Bedford Queens Park Bedford Kempston West & South Bedford South Thamesmead Bexley Belvedere & Lessness Heath Bexley Erith East Bexley Lesnes Abbey Bexley Slade Green & Crayford Marshes Bexley Lesney Farm & Colyers East Bexley Old Oscott Birmingham Perry Beeches East Birmingham Castle Vale Birmingham Birchfield East Birmingham -

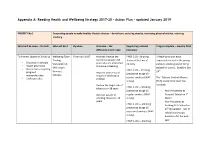

Appendix A: Reading Health and Wellbeing Strategy 2017-20 - Action Plan - Updated January 2019

Appendix A: Reading Health and Wellbeing Strategy 2017-20 - Action Plan - updated January 2019 PRIORITY No 1 Supporting people to make healthy lifestyle choices – dental care, reducing obesity, increasing physical activity, reducing smoking What will be done – the task Who will do it By when Outcome – the Supporting national Progress Update – January 2019 difference it will make indicators To Prevent Uptake of Smoking Wellbeing Team; From April 2017 Maintain/reduce the PHOF 2.03 - Smoking 3 Reading schools have Trading number of people >18 status at the time of expressed interest in the young - Education in schools Standards; CS; years who are estimated delivery person’s smoking and drinking - Health promotion to smoke in Reading S4H; Youth attitudinal survey. Deadline Dec - Quit services targeting PHOF 2.09i – Smoking th pregnant Services; 14 . Improve awareness of prevalence at age 15- women/families Schools; impact of smoking on current smokers (WAY The Tobacco Control Alliance - Underage sales children survey) [TCA] Coordinator work has Reduce the illegal sale of involved: PHOF 2.09ii – Smoking tobacco to >18 years prevalence at age 15 – - Year 9 Assembly at st Increase uptake of regular smokers (WAY Prospect School on 1 smoking cessation >18 survey) March. years - Year 9 students at PHOF 2.09iii – Smoking Reading Girls School on prevalence at age 15 – 27th November – rest of occasional smokers (WAY school year groups survey) booked in for the next PHOF 2.09iv – Smoking year prevalence at age 15 – - Year 7 students about regular smokers (SDD smoking health harms at survey) The Wren School on 7th November. Rest of PHOF 2.09v – Smoking school booked in for prevalence at age 15 – next year. -

Initial Proposals for New Parliamentary Constituency Boundaries in the South East Region Contents

Initial proposals for new Parliamentary constituency boundaries in the South East region Contents Summary 3 1 What is the Boundary Commission for England? 5 2 Background to the 2018 Review 7 3 Initial proposals for the South East region 11 Initial proposals for the Berkshire sub-region 12 Initial proposals for the Brighton and Hove, East Sussex, 13 Kent, and Medway sub-region Initial proposals for the West Sussex sub-region 16 Initial proposals for the Buckinghamshire 17 and Milton Keynes sub-region Initial proposals for the Hampshire, Portsmouth 18 and Southampton sub-region Initial proposals for the Isle of Wight sub-region 20 Initial proposals for the Oxfordshire sub-region 20 Initial proposals for the Surrey sub-region 21 4 How to have your say 23 Annex A: Initial proposals for constituencies, 27 including wards and electorates Glossary 53 Initial proposals for new Parliamentary constituency boundaries in the South East region 1 Summary Who we are and what we do Our proposals leave 15 of the 84 existing constituencies unchanged. We propose The Boundary Commission for England only minor changes to a further 47 is an independent and impartial constituencies, with two wards or fewer non -departmental public body which is altered from the existing constituencies. responsible for reviewing Parliamentary constituency boundaries in England. The rules that we work to state that we must allocate two constituencies to the Isle The 2018 Review of Wight. Neither of these constituencies is required to have an electorate that is within We have the task of periodically reviewing the requirements on electoral size set out the boundaries of all the Parliamentary in the rules. -

Changes to Bus Services in Brighton and Hove the Following Changes To

Changes to Bus Services in Brighton and Hove The following changes to bus services will take place in September 2018 c Route details Changes to current service Service provided Date of by change 1 Whitehawk - County Hospital On Saturday mornings the combined westbound service 1/1A frequency Brighton & Hove 16.09.18 - City Centre - Hove - will be slightly reduced between approximately 7am and 8am – from Buses Portslade – Valley Road - every 10 minutes to every 12 or 13 minutes. Mile Oak On Sunday mornings, the first three eastbound journeys will additionally serve Brighton Station. The journeys concerned are the 6.29am and 6.59am from New Church Road/Boundary Road, and the 7.14am from Mile Oak. 1A Whitehawk - County Hospital Please see service 1, above. Brighton & Hove 16.09.18 - City Centre - Hove - Buses Portslade – Mile Oak Road - Mile Oak N1 (night Whitehawk - County Hospital No change Brighton & Hove bus) - City Centre - Hove - Buses Portslade - Mile Oak - Downs Park - Portslade 2 Rottingdean - Woodingdean - Some early morning and early evening journeys that currently terminate Brighton & Hove 16.09.18 Sutherland Road - City at Shoreham High Street will be extended to start from or continue to Old Buses Centre - Hove - Portslade - Shoreham, Red Lion. Shoreham - Steyning On Saturdays, the 7.03am journey from Steyning will instead start from Old Shoreham, Red Lion, at 7.20am. 2B Hove - Old Shoreham Road - Minor timetable changes Brighton & Hove 16.09.18 Steyning Buses Date of Service No. Route details Changes to current service Service provided by Change 5 Hangleton - Grenadier – Elm On Sundays, there will be earlier buses. -

Welcome Helen Barnett Marketing Manager, Bracknell Regeneration Partnership Chairman, Executive Board

Welcome Helen Barnett Marketing Manager, Bracknell Regeneration Partnership Chairman, Executive Board I’m delighted to introduce myself as the new Chairman of Autumn 2006 No. 5 Bracknell Forest Partnership Executive Board. I’d like to thank Des Tidbury for his work as the chairman for the last six months. The newsletter for Bracknell Forest I hope to bring some of my skills to help improve the way Partnership we manage and communicate issues regarding the partnership over the next six months. Contents The September meeting of the Executive Board was very valuable and we all took away new and useful • Chairman’s welcome information. This newsletter provides you with a • Executive Board information sharing summary to share with your colleagues and peers. o Phoenix Project o Voluntary Sector Forum We will spend the next few weeks collating the ideas you o Connexions gave us for improving the way we communicate both o Local Development Framework with each other and with people across Bracknell Forest. Update We will come back to you with an improvement plan for • Consultation – Communications the December meeting – do come! • Bracknell Forest Sexual Health think tank In the meantime if you have any comments or suggestions about the Executive Board meetings or these newsletters, please email Claire Sharp, whose contact details are at the bottom of this page. Next Executive Board Meeting Helen Barnett, Marketing Manager Bracknell Regeneration Partnership 12 December 2006 9am start with refreshments available from 8.45am Executive Board Information Sharing Kitty Dancy Room, Sandhurst Town Council Phoenix Project Prepared by Bracknell Forest Borough Council on behalf of the Bracknell Forest Partnership. -

11K Donation from the DPS to Help LGBT Young People in Brighton and Hove Find a Home Through YMCA Downslink Group - Youth Advice Centre

Computershare Investor Services PLC The Pavilions Bridgwater Road Bristol BS99 6ZZ Telephone + 44 (0) 870 702 0000 Facsimile + 44 (0) 870 703 6101 www.computershare.com News Release Monday 27 February 2017 Date: Subject: £11k donation from The DPS to help LGBT young people in Brighton and Hove find a home through YMCA DownsLink Group - Youth Advice Centre Bristol, Monday 27 February 2017 – An £11,000 donation by The Deposit Protection Service (The DPS) will fund specialist support from YMCA DownsLink Group - Youth Advice Centre for LGBT young people in Brighton and Hove to help them find a home, the UK’s largest protector of tenancy deposits has announced. The Centre will train volunteers one-to-one to become ‘peer mentors’ and provide support to other members of the local LGBT community. Daren King, Head of Tenancy Deposit Protection at The DPS, said: “83,000 young people experience homelessness every year and the South East has the second highest rate of homeless applications in England. “As a result, we’re delighted to be supporting YMCA DownsLink Group - Youth Advice Centre’s fantastic work in helping LGBT young people in Brighton and Hove find a home.” YMCA DownsLink Group - Youth Advice Centre is a “one-stop shop” for advice and information for young people aged 13-25 years old in the City of Brighton and Hove. Julia Harrison, Advice Services Manager at YMCA DownsLink Group - Youth Advice Centre, said: “LGBT young people account for 13% of the total number of clients accessing our housing service, with a 50% increase in transgender clients since April 2016. -

Westdene Drive Brighton Bn1 5Hf

WESTDENE DRIVE BRIGHTON BN1 5HF Estate Agents VIRTUAL PROPERTY TOUR AVAILABLE £245,000 LEASEHOLD Westdene Drive is a quiet residential street located in the Westdene suburb of Brighton and Hove. The area is hugely popular with families and young professionals keen to find a spacious home within easy reach of the main transport links while being only a short hop to the city centre. There are a number of parks close by, as well as an excellent primary school and local shops. The property itself is a smart, modern, purpose-built apartment located on the ground floor of this well-maintained building. Access is to a wide, central hallway with all rooms located off this. At the far end of the hall is the lounge which is bright and spacious, with dual-aspect windows adding to the sense of light. Next door to this is the kitchen which has been fitted with a modern range of wall and base level units topped with contemporary work surfaces. There is a door from the kitchen opening to the balcony which benefits from a beautiful backdrop of the communal gardens. Next to the kitchen is the bathroom and separate wc; again, these have been finished in a smart contem- porary style. The master bedroom is across the corridor and this is a terrifically sized double and is complete with built-in wardrobes. The accommodation is completed by the second bedroom which is nicely sized and benefits from views across the gardens. Overall this is a superb two bedroom apartment and will make an excellent first buy or buy-to-let.