A Defense of the Privilege Against Self-Incrimination Andrew E

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Your Name Here

PHENOMENAL BODIES, PHENOMENAL GIRLS: HOW YOUNG ADOLESCENT GIRLS EXPERIENCE BEING ENOUGH IN THEIR BODIES by HILARY ELIZABETH HUGHES (Under the Direction of Mark D. Vagle) ABSTRACT Drawing on philosophers (Ahmed, 2006; Fanon, 1986; Heidegger, 1927, 1962, 1992; Merleau-Ponty, 1962) and social science scholars (Dahlberg, Dahlberg, & Nystrom, 2008; Vagle, 2009, 2010, 2011; van Manen, 1990, 2000) for this phenomenological study, I asked what it was like for the seventh grade girls who participated with me in a year-long writing group to experience moments where they found themselves in bodily-not-enoughness: moments when someone or something was telling them they were not enough of something in their bodies. Using a multigenre magazine format for the dissertation, I describe how I learned—as an adult, a qualitative researcher, a middle grades teacher, and a teacher educator—from these seventh grade girls how to be-enough in my own body, by illustrating various moments when some of the girls seemed to talk-back-TO those societal messages telling them they were not pretty- enough, thin-enough, English-speaking-enough, white-enough, popular-enough, or smart-enough by embodying some kind of resistance-to those messages. I then suggest that if we as adults, qualitative researchers, middle grades educators, and teacher educators wish to try and understand better how female young adolescents of color experience living in their bodies, we should begin listening differently so that we can begin seeing/knowing/thinking the bodies of young adolescents, -

37131054409156D.Pdf

YEZAD A Romance of the Unknown By GEORGE BABCOCK PUBLISHED BY CO-OPERATIVE PUBLISHING CO., INC. BRIDGEPORT, CONN. NEW YORK, N. Y. Copyright, November, 1922, by GEORGE BABCOCK All rights reserved To MY S1sTER, EVA STANTON (BABCOCK) BROWNING., this story 1s affectionately inscribed. GEORGE BABCOCK. Brooklyn, N. Y. November, 19ff. CHARACTERS l JOHN BACON, Aviator. 2 JuLIA BACON, His Wife. 3 PAUL BACON, Son. 4 ELLEN BACON, Daughter. 5 AnoLPH VON PosEN, Inventor, in love. 6 SALLY T1MPOLE, the Cook, also in love. 7 JASPER PERKINS } 8 SILAS CUMMINGS The old quaint cronies. 9 NANCY PRINDLE 10 DOCTOR PETER KLOUSE. 11 HESTER DOUGLASS} 12 F IN LEY D OU GLASS Grandchildren of the Doctor. 13 SAM WILLIS, the dreadful liar. 14 WILLIAM THADDEUS TITUS, Champion of several trades. 15 WILLIAM GRENNELL, the Village Blacksmith. 16 MINNA BACON } 17 B RENDA B ACON Children of Paul and Hester. 18 RoBERT DouGLAss, Son of Finley and Ellen. 19 CHARLOTTE Dun LEY, a Maiden of Mars. 20 CHRISTOPHER SPENCER, Astronomer of Mars. 21 FELIX CLAUDIO, the Devil's Son. 22 DocToR NATHAN ELIZABRAT of Mars. 23 MARCOMET, a Guard of the Great White \Vay. 24 JOHN BACON'S DUALITY. Note:-A Glossary of coined and unusual words and their mean ing, used by the author in Yezad, will be found on pages 449 to 463. CONTENTS CHAPTER PAGE I THE PRICE OF PROGRESS 1 II THE GHOST • 20 III NEW NEIGHBORS 33 IV DOCTOR KLOUSE 45 V HEREDITY VS. KLOUSE PHILOSOPHY 52 VI A DREADFUL LIAR • 57 VII AMONG THE ABORIGINES 71 VIII AN ODD EXPERIMENT . -

Why Some Men Kill

CONTENTS He n r . G d d ar In troducti on by Dr . y H o d I . Chapter , The Delinquent Moron Chapter II . , Psychology of Confessions of Crime Chapter III The Murder of William Booth and the Convie tion of William Branson and Mrs . Booth Chapter IV William Biggin Shows Warden Murphy Where He Concealed the Revolver a Chapter V . , Appe l to the Public for the Release of Wil liam Branson and Mrs . Booth . a an d He r Chapter VI . , The Murder of Mrs Daisy Wehrm n Child VII a . Ch pter , The Crime Indicates the Criminal ’ We h rm a n s D e a d Chapter VIII The Hair Found in Mrs . Hands IX ’ Chapter . , John Sierks Letters About the Murder ’ th e X . Chapter , Confirmation of John Sierks Confession of Murder Chapter XI Circumstantial Evidence XL ’ Supplement to Chapter , Containing Judge Pipes Brief II X . Chapter , Characteristics of Sadism . X e Chapter III Personal Character of Mr . Pend r Chapter XIV The Sadistic Murder of the Hill Family ’ B n Chapter XV . , William iggins Confessio Chapter XVI The Murder of Mary Spina XV Chapter II . , Conclusion f Pre ss o Pa ci$ c Coas t Res cue a nd Prot e ct ive Socie ty o n N G . mx s J . H S n a , medium grade w h o moron , confessed to kill ing Mrs . Wehrma n and her child i n Columbia S 1 91 1 County , Oregon , in eptember , , and a then repudi ted his confession . Chap 6 - 1 3 ters . -

CLAT-2021-LLB-Question-Paper-2

CONSORTIUM OF NATIONAL LAW UNIVERSITIES COMMON LAW ADMISSION TEST (CLAT) 2021 National Law School of India University Nagarbhavi, Bengaluru – 560 072 Contact No. 08047162020 Email: [email protected] Website: consortiumofnlus.ac.in July 23, 2021 NOTIFICATION FOR INVITING OBJECTIONS Candidates who appeared in CLAT-2021 for UG and PG Programmes on July 23, 2021 may file their objections, if any, on Consortium website. The portal for objection(s) will open at 09:00 P.M. on July 23, 2021 and close at 09:00 P.M. on July 24, 2021. After 09:00 P.M. on July 24, 2021 the link will be de-activated. No Objection(s) will be entertained thereafter. Objection(s) received over email or phone calls will not be entertained. A fee of Rs. 1,000/- (Rs. One Thousand only) is to be paid for each objection and if the objection turns out to be valid, the said fee will be refunded/remitted to the same account from which it was paid. No requests of depositing it in any other account will be entertained. Objection(s) without the prescribed fee will not be entertained. Important Note on Raising Objection(s): (a) Master Question Booklet and Master Answer Key will be uploaded on the Consortium website at 09:00 P.M. on July 23, 2021; (b) Students shall tally the Question Number from their own Question Booklet (Note: there are four different series of Question Booklets) with the Master Question Booklet and raise Objection only on appropriate Question Number(s) from Master Question Booklet. (c) If Candidates raise Objections on their own Question Booklet and the Question Number does not match with the Master Question Booklet, CLAT Office will not respond to such objection(s). -

06 10-27-09 TV Guide.Indd 1 10/27/09 7:56:14 AM

Page 6 THE NORTON TELEGRAM Tuesday, October 27, 2009 WEEK OF FRIDAY , OCT . 30 THROUGH THURSDAY , NOV . 5 Norton TV Listings: For your convenience the TV Listing is Brought to You by . Friday Evening October 30, 2009 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 KHGI/ABC Supernanny Ugly Betty 20/20 Local Nightline Jimmy Kimmel Live KBSH/CBS Ghost Whisperer Medium NUMB3RS Local Late Show-Letterman Late Late KSNK/NBC Law & Order Dateline NBC The Jay Leno Show Local Tonight Show Late Nigh FOX House Local Cable Channels A&E Criminal Minds Criminal Minds Criminal Minds CSI: Miami Criminal Minds AMC Young Frankenstein Amityvl Horror ANIM Mr. and Mrs. Wolfman I'm Alive Pit Bulls-Parole I'm Alive Mr. and Mrs. Wolfman CNN Campbell Brown Larry King Live Anderson Cooper 360 Larry King Live DISC Dirty Jobs Lobstermen Lobstermen Dirty Jobs Lobstermen DISN Wizards The Suite Phineas Phineas Wizards Montana Phineas So Raven The Suite Cory E! Lamas Dating 2 Girls Girls The Soup The Soup Chelsea E! News Chelsea The Soup ESPN NBA Basketball NBA Basketball ESPN2 College Football SportsCenter Baseball NFL Live FAM Scooby-Doo 2 Funniest Home Videos The 700 Club '70s Show '70s Show FX The Invisible '70s Show '70s Show Sons of Anarchy The Invisible HGTV Property Property House Buck House House The Unsel My First House Buck HIST Modern Marvels Modern Marvels Modern Marvels Modern Marvels Modern Marvels LIFE DietTribe Project Runway Project Runway Models Will Frasier Medium MTV Super Psycho Ulalume: Howling Scream 3 Ulalume NICK The Troop The Troop Lopez Lopez Lopez Lopez The Nanny The Nanny The Nanny The Nanny SCI Interview-Vamp Stargate Universe Sanctuary Stargate Universe Sanctuary SPIKE Forrest Gump Forrest Gump TBS Fam. -

Las Vegas in Singapore: Casinos and the Taming of Vice

Las Vegas in Singapore: Casinos and the Taming of Vice By Kah-Wee Lee A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In Architecture and the Designated Emphasis in Global Metropolitan Studies in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Nezar AlSayyad, Chair Professor C. Greig Crysler Professor Andrew M. Shanken Professor Aihwa Ong Fall 2012 Las Vegas in Singapore: Casinos and the Taming of Vice ©2012 Kah-Wee Lee 1 Abstract Las Vegas in Singapore: Casinos and the Taming of Vice by Kah-Wee Lee Doctor of Philosophy in Architecture University of California, Berkeley Professor Nezar AlSayyad, Chair This dissertation investigates the historical formation of the modern casino as a “dividing practice” that cuts society along moral, legal and economic lines. It analyzes specific episodes in Singapore’s and Las Vegas’ histories when the moral problem of vice was transformed into a series of practical interventions devised by lawyers, detectives, architects and bureaucrats to criminalize and legalize gambling. Spatial containment and aesthetic form are key considerations and techniques in these schemes. I show how such schemes revolve around the complex management of the political costs and practical limits of changing the moral-legal status of gambling, whether it is to criminalize a popular form of illegality or to legalize an activity that threatens the normative order of society. The rise of the modern casino as a spatially bounded and concentrated form of gambling that is seamless with corporate management practices and popular culture is an indication of how far such costs and limits have been masked and stretched. -

The Dalhousie Undergraduate History Journal 2013

The Dalhousie Undergraduate History Journal 2013 Pangaea Editor Kate Park Assistant Editors Daisy Ramsden Lindsay Oliver Cover Design Jeremy Bridge Editorial Board Conner Coles Rebecca Riordon Stephanie Conrod Alex Sisley Sarah Kasupski Shoshana Deutsh Faculty Advisors Dr. Justin Roberts Dr. Michael Ramsay Dr. Jack Mitchell Dr. Krista Kesselring Dr. Cynthia Neville Dr. Denis Kozlov Dr. Shirley Tillotson Dr. Roger Marsters Special Thanks The Dalhousie History Department The Dalhousie Undergraduate History Society Tina Jones Dr. Ruth Bleasdale Editor’s Note “To me, history ought to be a source of pleasure. It isn’t just part of our civic responsibility. To me, it’s an enlargement of the experience of being alive, just the way literature or art or music is.” ― David McCullough For us, history is a source of pleasure; it is the reason we came to school, and it is the reason for this journal. Pangaea 2013 is a result of much hard work and dedication, from our contributors, editors, faculty members, and staff. Each contributor was able to bring a fresh perspective to the topics they covered in their respective fields, thus creating a diverse and engrossing read. Many hours of research and writing have brought us the thorough and thought provoking papers within these pages. Papers in this journal come from a variety of historical backgrounds and cover diverse topics, from Ancient Rome to an English prison to Soviet Russia. While these papers were written for a variety of classes each and every paper reflects the individual style of its author and their personal interests. Each editor was also able to bring their solid and differing opinions to the table giving way to many hours of discourse and many more emails. -

PEOPLE V. CHELSEA KORWATCH Fact Pattern

PEOPLE V. CHELSEA KORWATCH Fact Pattern: In 2010 a website launched on the dark web operating at the URL www.GaultsGulch.yg. Gault’s Gulch was a site accessible only by a Tor browser*, which allowed users to buy and sell goods and services using Bitcoin**. Gault’s Gulch operated under the motto “everything at a price” and allowed for peer-to-peer transactions. Although the site allowed for peer-to-peer transactions it was maintained by a user known as “Captain Taggart,” who received a small cut of all deals. Gault’s Gulch boasted thousands of items for sale that are illegal in some countries, ranging from fringe collectors’ items such as Nazi memorabilia (which is illegal in France) to bootlegged movies and software (which is illegal in member nations of the World Patent Treaty which does not include Taiwan , Argentina, and several others). Additionally the site served as a hub for people selling items that are illegal in all nations such as illicit drugs and violent services such as murder-for-hire. In 2013, Captain Taggart posted a “buy” item offering $50,000 to any person who killed Casey Bilty, an officer of the Northrop Police Department who had been acquitted in the shooting death of a suspect in a drug bust linked to Gault’s Gulch. Given the risky and unusual nature of the posting, Captain Taggart breached the standard protocol of paying in Bitcoin and offered to provide $10,000 cash up front and $40,000 upon completion. The bid was accepted by a user known as Pancakes. -

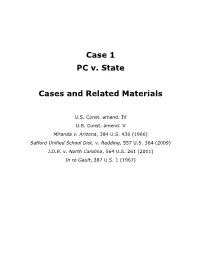

Case 1 PC V. State Cases and Related Materials

Case 1 PC v. State Cases and Related Materials U.S. Const. amend. IV U.S. Const. amend. V Miranda v. Arizona, 384 U.S. 436 (1966) Safford Unified School Dist. v. Redding, 557 U.S. 364 (2009) J.D.B. v. North Carolina, 564 U.S. 261 (2011) In re Gault, 387 U.S. 1 (1967) Amendment IV. Searches and Seizures; Warrants, USCA CONST Amend. IV-Search... United States Code Annotated Constitution of the United States Annotated Amendment IV. Searches and Seizures; Warrants U.S.C.A. Const. Amend. IV-Search and Seizure; Warrants Amendment IV. Searches and Seizures; Warrants Currentness The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no Warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by Oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized. <Historical notes and references are included in the full text document for this amendment.> <For Notes of Decisions, see separate documents for this amendment.> U.S.C.A. Const. Amend. IV-Search and Seizure; Warrants, USCA CONST Amend. IV-Search and Seizure; Warrants Current through P.L. 115-68. End of Document © 2017 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works. © 2017 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works. 1 Amendment V. Grand Jury Indictment for Capital Crimes;..., USCA CONST Amend.... United States Code Annotated Constitution of the United States Annotated Amendment V. Grand Jury; Double Jeopardy; Self-Incrimination; Due Process; Takings U.S.C.A. -

Extensions of Remari(S Hon. Stuart Symington Hon. Noah

1792 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD- HOUSE February 5 EXTENSIONS OF REMARI(S Need fo.r Positive Progr~ms in power to light and heat a city of 10,000 on a licans believe in high wages for money-and. pack of enriched uranium that could be the Democratic Party, high wages for people. Atomic-Space Age sent in by air mail. "I do not accuse the Republicans of bring The Senator said there is much to be ing on a depression. But like the safety EXTENSION OF REMARKS done in the field of medical and agricul engineers say about workers who have re tural research. OP' peated accidents, -that they are 'accident "And we are not even across the threshold prone'-I do charge that the Republicans of the use of atomic power in tranSporta are depression prone." HON. STUART SYMINGTON tion," he added. OF MISSOURI MoNRONEY was introduced by former Pres Senator MoNRONEY also aimed some barbs ident Harry S Truman, who presented the IN THE SENATE OF THE UNITED STATES at John Foster Dulles, Secretary of State, Senator as "an old friend who knows what Wednesday, February 5, 1958 and Ezra Taft Benson, Secretary of Agricul he's doing and where he's going; and who ture. never talks idly on any subject." Mr. SYMINGTON. Mr. President, The Senator accused the Republicans of The dinner was opened by James L. Wil Missouri was most honored last Satur lack of imagination and lack of initiative in liams, Jackson County Democratic chair day night by the presence of the dis the field of foreign affairs. -

(Title of the Thesis)*

Shameful Attachments / Attachments to Shame: Affective Unreliability and the Contemporary Moment by Taryn Beukema A thesis submitted to the Department of English Language and Literature in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Queen’s University Kingston, Ontario, Canada August, 2015 Copyright © Taryn Beukema, 2015 Abstract This dissertation undertakes a critical consideration of the productive and beneficent potential of shame. By examining texts in which characters or individuals depart from more traditional narratives, experiences, and/or manifestations of shame, this project aims to deconstruct the historically-entrenched definition of shame as a negative affect and provide a more inclusive and potentially liberating formulation. The introductory chapter charts the dominant trends in shame theory since Freud and articulates some of the main questions that propel the arguments of this dissertation: how do attachments to shame form? What is it that attracts individuals to shame? How do we begin to conceive of a form of shame that does not operate as shame “should?” Via close-readings of Rick Moody’s The Ice Storm, Chapter Two begins to answer some of these questions, examining the relation between shame and desire in order to demonstrate not only the necessity of desire to shame’s instantiation, but the ways in which shame alters our understanding of discourses of desire. Chapter Three investigates the life, writing, and art of Bob Flanagan, performance artist and “supermasochist,” to reveal the sometimes erotic nature of shame. Chapter Four’s analysis of NBC’s The Biggest Loser focuses on the more familiar narrative of shame as an enforcer of social norms, suggesting that the ostensibly passive desire to see others humiliated (schadenfreude) is actually a form of active participation in the modes of governmentality embedded in reality television and thus reveals the ubiquity of attachments to shame in contemporary culture. -

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Las Vegas in Singapore: Casinos and the Taming of Vice Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5fd9x8cg Author Lee, Kah-Wee Publication Date 2012 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Las Vegas in Singapore: Casinos and the Taming of Vice By Kah-Wee Lee A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In Architecture and the Designated Emphasis in Global Metropolitan Studies in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Nezar AlSayyad, Chair Professor C. Greig Crysler Professor Andrew M. Shanken Professor Aihwa Ong Fall 2012 Las Vegas in Singapore: Casinos and the Taming of Vice ©2012 Kah-Wee Lee 1 Abstract Las Vegas in Singapore: Casinos and the Taming of Vice by Kah-Wee Lee Doctor of Philosophy in Architecture University of California, Berkeley Professor Nezar AlSayyad, Chair This dissertation investigates the historical formation of the modern casino as a “dividing practice” that cuts society along moral, legal and economic lines. It analyzes specific episodes in Singapore’s and Las Vegas’ histories when the moral problem of vice was transformed into a series of practical interventions devised by lawyers, detectives, architects and bureaucrats to criminalize and legalize gambling. Spatial containment and aesthetic form are key considerations and techniques in these schemes. I show how such schemes revolve around the complex management of the political costs and practical limits of changing the moral-legal status of gambling, whether it is to criminalize a popular form of illegality or to legalize an activity that threatens the normative order of society.