(Title of the Thesis)*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Layout 1 (Page 2)

SEPTEMBER 9-15, 2011 CCURRENTSURRENTS The News-Review’s guide to arts, entertainment and television ToastToast ofof thethe towntown WinemakersWinemakers featurefeature theirtheir concoctionsconcoctions atat thethe 42nd42nd annualannual UmpquaUmpqua ValleyValley WineWine ArtArt andand MusicMusic FestivalFestival MICHAEL SULLIVAN/The News-Review INSIDE: What’s Happening/3 Calendar/4 Book Review/10 Movie Review/14 TV/15 Page 2, The News-Review Roseburg, Oregon, Currents—Thursday, September 8, 2011 * &YJUt$BOZPOWJMMF 03t*OGPt3FTtTFWFOGFBUIFSTDPN Roseburg, Oregon, Currents—Thursday, September 8, 2011 The News-Review, Page 3 what’s HAPPENING TENMILE An artists’ reception will be held from 5 to 7 p.m. Friday at Remembering GEM GLAM the gallery, 638 W. Harrison St., Roseburg. 9/11 movie, songs Also hanging is art by pastel A special 9/11 remembrance painter Phil Bates, mixed event will be held at 5 p.m. media artist Jon Leach and Sunday at the Tenmile Com- acrylic painter Holly Werner. munity United Methodist Fisher’s is open regularly Church, 2119 Tenmile Valley from 9 to 5 p.m. Monday Road. through Friday. The event includes a show- Information: 541-817-4931. ing of a one-hour movie, “The Cross and the Towers,” fol- lowed by patriotic music and MYRTLE CREEK sing-alongs with musicians Mark Baratta and Scott Van Local artist’s work Atta. hangs at gallery The event is free, but dona- Myrtle Creek artist Darlene tions for musicians’ expenses Musgrave is the featured artist are welcome. Refreshments at Ye Olde Art Shoppe. will be served. An artist’s reception for Information: 541-643-1636. Musgrave will be held from 10 a.m. -

Jobs Rally Goes Off As Planned

A1 Vol. 131, Issue 249 .50 INDEX Obits ... page 3 Opinions ... page 4 Business ... page 5 Sports ... page 6 Classifieds ... page 7 Scattered Showers Serving Surry County since 1880. High Low Braves take Dodgers Page 6 Forsubscriptions, call 786-4141. 70 61 The Mount Airy News www.mtairynews.com Printed on recycled newspaper Tuesday, September 6, 2011 Weekend event to celebrate agriculture Staff Report DOBSON — The sixth annual Celebrating Agricul- ture festival will take place this Saturday at Fisher River Park. The festival, put on each year by the Surry County Cooperative Extension, is designed to provide a chance for families to learn more about agriculture and farming and its role in daily life. “It’s going to be awe- some. I’m so excited about it,” said Joanna Radford, extension agent who is orga- nizing the event. Once again there will be plenty of activities for children during the event including rides, games and other activities. There will be a 4-H activity area for kids and a train ride made of barrels to take kids around MORGAN WALL/THE NEWS the park. Kids will even be Mount Airy Mayor Deborah Cochran, along with Surry County Board of Commissioner Chairman Paul Johnson, Mount Airy City Com- able to visit a chicken coop missioner Steve Yokeley, Mount Airy City Commisioner Todd Harris and Mount Airy City Commissioner Dean Brown, address the crowd and help collect eggs. There also will be bounce houses gathered for Monday evening’s jobs rally. for kids. Antique, classic and new tractors will be on display and local craftsmen and farmers will be putting on Jobs rally goes a blacksmithing demonstra- tion and making corn meal. -

Your Name Here

PHENOMENAL BODIES, PHENOMENAL GIRLS: HOW YOUNG ADOLESCENT GIRLS EXPERIENCE BEING ENOUGH IN THEIR BODIES by HILARY ELIZABETH HUGHES (Under the Direction of Mark D. Vagle) ABSTRACT Drawing on philosophers (Ahmed, 2006; Fanon, 1986; Heidegger, 1927, 1962, 1992; Merleau-Ponty, 1962) and social science scholars (Dahlberg, Dahlberg, & Nystrom, 2008; Vagle, 2009, 2010, 2011; van Manen, 1990, 2000) for this phenomenological study, I asked what it was like for the seventh grade girls who participated with me in a year-long writing group to experience moments where they found themselves in bodily-not-enoughness: moments when someone or something was telling them they were not enough of something in their bodies. Using a multigenre magazine format for the dissertation, I describe how I learned—as an adult, a qualitative researcher, a middle grades teacher, and a teacher educator—from these seventh grade girls how to be-enough in my own body, by illustrating various moments when some of the girls seemed to talk-back-TO those societal messages telling them they were not pretty- enough, thin-enough, English-speaking-enough, white-enough, popular-enough, or smart-enough by embodying some kind of resistance-to those messages. I then suggest that if we as adults, qualitative researchers, middle grades educators, and teacher educators wish to try and understand better how female young adolescents of color experience living in their bodies, we should begin listening differently so that we can begin seeing/knowing/thinking the bodies of young adolescents, -

Friday Morning, Nov. 6

FRIDAY MORNING, NOV. 6 6:00 6:30 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 VER COM 4:30 KATU News This Morning (N) Good Morning America (N) (cc) 78631 AM Northwest Be a Millionaire The View (N) (cc) (TV14) 64438 Live With Regis and Kelly (N) (cc) 2/KATU 2 2 (cc) (Cont’d) 297235 (cc) 55693 86051 77902 KOIN Local 6 Early News 81631 The Early Show (N) (cc) (TVG) 65411 Let’s Make a Deal (N) (cc) (TVPG) The Price Is Right (N) (cc) (TVG) The Young and the Restless (N) (cc) 6/KOIN 6 6 at 6 58490 74438 99148 (TV14) 15952 Newschannel 8 at Sunrise at 6:00 Today “Sesame Street” anniversary; Jeff Corwin; Fran Drescher; makeovers. (N) (cc) (TVG) 894186 Rachael Ray (cc) (TVG) 97780 8/KGW 8 8 AM (N) (cc) 28761 Power Yoga Between the Lions Curious George Sid the Science Super Why! Dinosaur Train Sesame Street Big Bird & Snuffy Clifford the Big Dragon Tales WordWorld (TVY) Martha Speaks 10/KOPB 10 10 18896 (TVY) 18709 (TVY) 34235 Kid (TVY) 46070 (TVY) 59070 (TVY) 58341 Talent Show. (TVY) 27544 Red Dog 92761 (TVY) 45877 86525 (TVY) 87254 Good Day Oregon-6 (N) 79419 Good Day Oregon (N) 58815 The 700 Club (cc) (TVPG) 12612 Paid 27457 Paid 63273 The Martha Stewart Show (N) (cc) 12/KPTV 12 12 (TVG) 57186 Key of David Paid 17235 Paid 33761 Paid 52896 Through the Bible Life-Robison Paid 56525 Paid 87983 Paid 31815 Paid 52709 Paid 93457 Paid 94186 22/KPXG 5 5 (TVG) 62380 66902 65273 Praise-A-Thon (Left in Progress) Fundraising event. -

37131054409156D.Pdf

YEZAD A Romance of the Unknown By GEORGE BABCOCK PUBLISHED BY CO-OPERATIVE PUBLISHING CO., INC. BRIDGEPORT, CONN. NEW YORK, N. Y. Copyright, November, 1922, by GEORGE BABCOCK All rights reserved To MY S1sTER, EVA STANTON (BABCOCK) BROWNING., this story 1s affectionately inscribed. GEORGE BABCOCK. Brooklyn, N. Y. November, 19ff. CHARACTERS l JOHN BACON, Aviator. 2 JuLIA BACON, His Wife. 3 PAUL BACON, Son. 4 ELLEN BACON, Daughter. 5 AnoLPH VON PosEN, Inventor, in love. 6 SALLY T1MPOLE, the Cook, also in love. 7 JASPER PERKINS } 8 SILAS CUMMINGS The old quaint cronies. 9 NANCY PRINDLE 10 DOCTOR PETER KLOUSE. 11 HESTER DOUGLASS} 12 F IN LEY D OU GLASS Grandchildren of the Doctor. 13 SAM WILLIS, the dreadful liar. 14 WILLIAM THADDEUS TITUS, Champion of several trades. 15 WILLIAM GRENNELL, the Village Blacksmith. 16 MINNA BACON } 17 B RENDA B ACON Children of Paul and Hester. 18 RoBERT DouGLAss, Son of Finley and Ellen. 19 CHARLOTTE Dun LEY, a Maiden of Mars. 20 CHRISTOPHER SPENCER, Astronomer of Mars. 21 FELIX CLAUDIO, the Devil's Son. 22 DocToR NATHAN ELIZABRAT of Mars. 23 MARCOMET, a Guard of the Great White \Vay. 24 JOHN BACON'S DUALITY. Note:-A Glossary of coined and unusual words and their mean ing, used by the author in Yezad, will be found on pages 449 to 463. CONTENTS CHAPTER PAGE I THE PRICE OF PROGRESS 1 II THE GHOST • 20 III NEW NEIGHBORS 33 IV DOCTOR KLOUSE 45 V HEREDITY VS. KLOUSE PHILOSOPHY 52 VI A DREADFUL LIAR • 57 VII AMONG THE ABORIGINES 71 VIII AN ODD EXPERIMENT . -

Tv Guide Pg1b 9-27.Indd

The Goodland Star-News / Tuesday, Sept. 27, 2011 1b All Mountain Time, for Kansas Central TIme Stations subtract an hour TV Channel Guide Tuesday Evening September 27, 2011 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 ABC 28 ESPN 57 Cartoon Net 21 TV Land 41 Hallmark Dancing With Stars Body of Proof Local Nightline Jimmy Kimmel Live S&T Eagle CBS NCIS NCIS: Los Angeles Unforgettable Local Late Show Letterman Late 29 ESPN 2 58 ABC Fam 22 ESPN 45 NFL NBC The Biggest Loser Parenthood Local Tonight Show w/Leno Late 2 PBS KOOD FOX Glee New Girl Raising Local 2 PBS KOOD 30 ESPN Clas 59 TV Land 23 ESPN 2 47 Food Cable Channels 3 KWGN WB 31 Golf 60 Hallmark 3 NBC-KUSA 24 ESPN Nws 49 E! A&E Storage Storage Storage Storage Storage Storage Storage Storage Wars Local 4 ABC-KLBY AMC The Mummy The Mummy Local 5 KSCW WB 32 Speed 61 TCM 25 TBS 51 Travel ANIM Madagascar River Monsters Madagascar Local 6 ABC-KLBY 6 Weather BET 33 Versus 62 AMC 26 Animal 54 MTV Preacher's Kid The Perfect Man Wendy Williams Show Prchr Kid Local 7 CBS-KBSL BRAVO Rachel Zoe Project Rachel Zoe Project Rachel Zoe Project Rachel Zoe Project Most Eligible Dallas 7 KSAS FOX 34 Sportsman 63 Lifetime 27 VH1 55 Discovery CMT Local Local Extreme Makeover Grumpier Old Men Angels 8 NBC-KSNK 8 NBC-KSNK 28 TNT 56 Fox Nws CNN Piers Morgan Tonight Anderson Cooper 360 John King, USA Piers Morgan Tonight Anderson Local 35 NFL 64 Oxygen 9 Eagle COMEDY Tosh.0 Tosh.0 Tosh.0 Work. -

A Heart Full of Goodness Luke 6:39-49

A Sermon Rev. W. Kevin Holder Grace Baptist Church Bryans Road, Maryland January 7, 2018 A Heart Full of Goodness Luke 6:39-49 In the reality television series Storage Wars, professional buyers visit storage facilities throughout the state of California and bid on the contents of the lockers. Before each locker is auctioned, the buyers are given five minutes to inspect the contents from the doorway. They can’t actually enter the locker or touch any of the items until the auctions are complete. This means that a buyer has to have a good eye and bold instincts to estimate the value of the goods. After the day's auctions are complete, the winning bidders get to sort through the lockers, estimating the prices they’ll set on the contents if they want to put items up for resale. In the case of an unusual item, they might consult an expert for appraisal. On the screen are running totals that display the cost versus estimated total value. Then at the end of the episode, there’s a final tally of the buyer’s net profit or loss. During the show’s first season, a new member named Jarrod, who had lost several auctions to the veteran bidders, vowed to win the next unit up for bid. A visual scan of the unit revealed some cardboard boxes, newspapers, and old bottles, as well as a large combination safe in the middle of the floor. Imagining that the safe might be filled with gems, gold bars, bearer bonds, land deeds, or other riches, Jarrod made a hefty bid of $1,500. -

The Cable Network in an Era of Digital Media: Bravo and the Constraints of Consumer Citizenship

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations Dissertations and Theses Fall August 2014 The Cable Network in an Era of Digital Media: Bravo and the Constraints of Consumer Citizenship Alison D. Brzenchek University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_2 Part of the Communication Technology and New Media Commons, Critical and Cultural Studies Commons, Cultural History Commons, Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, Film and Media Studies Commons, History of Science, Technology, and Medicine Commons, and the Political Economy Commons Recommended Citation Brzenchek, Alison D., "The Cable Network in an Era of Digital Media: Bravo and the Constraints of Consumer Citizenship" (2014). Doctoral Dissertations. 55. https://doi.org/10.7275/bjgn-vg94 https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_2/55 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations and Theses at ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE CABLE NETWORK IN AN ERA OF DIGITAL MEDIA: BRAVO AND THE CONSTRAINTS OF CONSUMER CITIZENSHIP A Dissertation Presented by ALISON D. BRZENCHEK Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2014 Department -

Football Cleveland Browns Vs

THE HERALD The REPUBLICAN Star THE NEWS SUN September 18 - September 24, 2011 tvweekly tvweeklyT ELEVISION L ISTINGS "New Girl" is just one of the new series on Fox's fall schedule - page 2 7UXVWWKH 0LGDV 7RXFK See Midas Mike 30 YEARS OF for ALL of your EXPERIENCE! AUTO CARE NEEDS! • Brakes • Oil Changes • Tires • Emissions • Engine Diagnostics • Alignments • Alternators • Factory Scheduled Maintenance • Starters • Exhaust • Bulbs • Batteries • Radiators • Inspections • Tune-ups • Timing Belts • Shocks & Struts • Belts & Hoses • And more! Open: M-F 7:30 - 5; Sat. 7:30 - Noon 2401 N. Wayne St. Angola, IN (260) 665-3465 Don Gura, Agent Look no further. 633 N. Main St., Having one special person Kendallville for your car, home and 347-FARM (3276) life insurance lets you get www.dongura.net down to business with the rest of your life. It’s what I do. GET TO A BETTER STATE™. CALL ME TODAY. State Farm Mutual Automobile Insurance Company, State Farm Indemnity Company, State Farm Fire and Casualty Company, 1101201 State Farm General Insurance Company, Bloomington, IL 2 • September 18 - September 24, 2011 • THE NEWS SUN • THE HERALD REPUBLICAN • THE STAR Star-power surplus Fox boasts big-name stars in fall lineup Rosalyn Stevens ties, and the comedy really comes out of the Factor" -- the star quality that brought us TV Media characters," Deschanel told "Access the likes of Leona Lewis. Cowell is back Hollywood." "I'm really excited. I love with former "American Idol" judge Paula Romantic comedy, science fiction, shooting it, and every week we have new Abdul, along with Pussycat Dolls lead singer animation -- there's something for everyone amazing scripts that are so funny." Nicole Sherzinger and record executive L.A. -

Why Some Men Kill

CONTENTS He n r . G d d ar In troducti on by Dr . y H o d I . Chapter , The Delinquent Moron Chapter II . , Psychology of Confessions of Crime Chapter III The Murder of William Booth and the Convie tion of William Branson and Mrs . Booth Chapter IV William Biggin Shows Warden Murphy Where He Concealed the Revolver a Chapter V . , Appe l to the Public for the Release of Wil liam Branson and Mrs . Booth . a an d He r Chapter VI . , The Murder of Mrs Daisy Wehrm n Child VII a . Ch pter , The Crime Indicates the Criminal ’ We h rm a n s D e a d Chapter VIII The Hair Found in Mrs . Hands IX ’ Chapter . , John Sierks Letters About the Murder ’ th e X . Chapter , Confirmation of John Sierks Confession of Murder Chapter XI Circumstantial Evidence XL ’ Supplement to Chapter , Containing Judge Pipes Brief II X . Chapter , Characteristics of Sadism . X e Chapter III Personal Character of Mr . Pend r Chapter XIV The Sadistic Murder of the Hill Family ’ B n Chapter XV . , William iggins Confessio Chapter XVI The Murder of Mary Spina XV Chapter II . , Conclusion f Pre ss o Pa ci$ c Coas t Res cue a nd Prot e ct ive Socie ty o n N G . mx s J . H S n a , medium grade w h o moron , confessed to kill ing Mrs . Wehrma n and her child i n Columbia S 1 91 1 County , Oregon , in eptember , , and a then repudi ted his confession . Chap 6 - 1 3 ters . -

CLAT-2021-LLB-Question-Paper-2

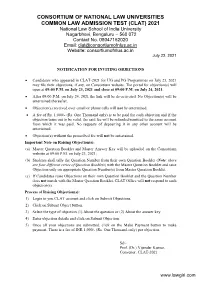

CONSORTIUM OF NATIONAL LAW UNIVERSITIES COMMON LAW ADMISSION TEST (CLAT) 2021 National Law School of India University Nagarbhavi, Bengaluru – 560 072 Contact No. 08047162020 Email: [email protected] Website: consortiumofnlus.ac.in July 23, 2021 NOTIFICATION FOR INVITING OBJECTIONS Candidates who appeared in CLAT-2021 for UG and PG Programmes on July 23, 2021 may file their objections, if any, on Consortium website. The portal for objection(s) will open at 09:00 P.M. on July 23, 2021 and close at 09:00 P.M. on July 24, 2021. After 09:00 P.M. on July 24, 2021 the link will be de-activated. No Objection(s) will be entertained thereafter. Objection(s) received over email or phone calls will not be entertained. A fee of Rs. 1,000/- (Rs. One Thousand only) is to be paid for each objection and if the objection turns out to be valid, the said fee will be refunded/remitted to the same account from which it was paid. No requests of depositing it in any other account will be entertained. Objection(s) without the prescribed fee will not be entertained. Important Note on Raising Objection(s): (a) Master Question Booklet and Master Answer Key will be uploaded on the Consortium website at 09:00 P.M. on July 23, 2021; (b) Students shall tally the Question Number from their own Question Booklet (Note: there are four different series of Question Booklets) with the Master Question Booklet and raise Objection only on appropriate Question Number(s) from Master Question Booklet. (c) If Candidates raise Objections on their own Question Booklet and the Question Number does not match with the Master Question Booklet, CLAT Office will not respond to such objection(s). -

Grayson County's Full-Coverage Community Newspaper

4 1 7 7 9 1 • GRAYSON COUNTY’S FULL-COVERAGE COMMUNITY NEWSPAPER • SATURDAY, NOVEMBER 12, 2011 • IN OUR 119TH YEAR • 75 CENTS NEWS STAND, 25 CENTS DELIVERED News-G40 PUBLIC SQUARE., LEITCHFIELD, KY. • COPYRIGHT 2009 • 270.259.9622 • waww.gcnewsgazettze.com • Vol. 13ette0, Issue 087 Admissions agreement benefits Grayson County By Rebecca Morris schools simultaneously. In a statement, ECTC President/CEO And with ECTC planning to build a new Reporter Joint admission will give students access Thelma White said the agreement will campus in Leitchfield, the joint admissions to a full range of services at both institu- allow a seamless transition from associate’s agreement means a broadening of the high- [email protected] tions, said Brian Meredith, WKU’s associ- degree programs to bachelor’s degree pro- er education opportunities expected to be ate vice president for enrollment manage- grams and allow area students to complete available in Grayson County in coming A new agreement could help Grayson ment, who was part of the team that final- most of their study closer to home. years. County students earn a degree from ized the agreement. WKU President Gary Ransdell noted the ECTC spokeswoman Mary J. King said Western Kentucky University without driv- “The timing of the agreement works agreement will allow students to complete the joint admissions agreement will cover ing any farther than Leitchfield. well with Kentucky’s move towards a their associates degree at ECTC, then con- all the college’s campuses as well as its-off On Nov. 10, WKU and Elizabethtown seamless pathway to a four-year degree,” tinue their education at the university’s campus class sites.