The Image of Romanian State in Bukovina Between the Two World Wars

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PEP: Zastavna District Administration, Chernivtsi Oblast (Region)

Logo • About • blog • Investigations • Contacts • Open Data • Scoring uk • About • blog • Investigations • Contacts • Open Data • Scoring content • Main page • Politically Exposed Persons • Zastavna District Administration, Chernivtsi Oblast (Region) Last dossier update: Feb. 27, 2021 PDF photo Zastavna District Administration, Chernivtsi Oblast (Region) Сategory State agency Taxpayer's 04062133 number Current state on the dissolvement stage since Jan. 28, 2021 59400, Чернівецька обл., Заставнівський р-н, місто Address Заставна, ВУЛ. В. ЧОРНОВОЛА, будинок 6 icon Connected PEPs Type of Власність, Name Period connection % Confirmed: Feb. 27, 2021 Jan. 30, РОЗПОРЯДЖЕННЯ Kozariichuk Head of the 2020 — ПРЕЗИДЕНТА Dmytro District State Feb. №81/2020-рп Vasylovych Administration 26, РОЗПОРЯДЖЕННЯ 2021 ПРЕЗИДЕНТА №113/2021-рп March Confirmed: July 15, 2019 Head of the 31, Kitar Yurii Відповідь АПУ.pdf District State 2015 — Vasylovych РОЗПОРЯДЖЕННЯ Administration July 11, ПРЕЗИДЕНТА 2019 №197/2019-рп Acting Head July 29, Moldovan of District 2019 — Vasyl State Jan. 30, Confirmed: Jan. 31, 2020 Mykolaiovych Administration 2020 Show more Show less Visualization of connections icon Structure Власність, Name Position Period % Confirmed: Feb. 27, 2021 Jan. 30, РОЗПОРЯДЖЕННЯ Kozariichuk Head of the 2020 — ПРЕЗИДЕНТА Dmytro District State Feb. №81/2020-рп Vasylovych Administration 26, РОЗПОРЯДЖЕННЯ 2021 ПРЕЗИДЕНТА №113/2021-рп March Confirmed: July 15, 2019 Head of the 31, Kitar Yurii Відповідь АПУ.pdf District State 2015 — Vasylovych РОЗПОРЯДЖЕННЯ Administration -

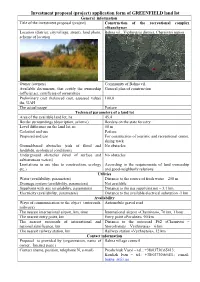

Investment Proposal (Project) Application Form of GREENFIЕLD

Investment proposal (project) application form of GREENFIЕLD land lot General information Title of the investment proposal (project) Construction of the recreational complex «Stanchyna» Location (district, city/village, street), land photo, Bahna vil., Vyzhnytsia district, Chernivtsi region scheme of location Owner (owners) Community of Bahna vil. Available documents, that certify the ownership General plan of construction (official act, certificate of ownership) Preliminary cost (balanced cost, assessed value) 100,0 ths. UAH The actual usage Pasture Technical parameters of a land lot Area of the available land lot, ha 45,4 Border surroundings (description, scheme) Borders on the state forestry Level difference on the land lot, m 50 m Cadastral end use Pasture Proposed end use For construction of touristic and recreational center, skiing track Ground-based obstacles (risk of flood and No obstacles landslide, ecological conditions) Underground obstacles (level of surface and No obstacles subterranean waters) Limitations in use (due to construction, ecology According to the requirements of land ownership etc.) and good-neighborly relations Utilities Water (availability, parameters) Distance to the source of fresh water – 250 m Drainage system (availability, parameters) Not available Supplying with gas (availability, parameters) Distance to the gas supplying net – 3,1 km. Electricity (availability, parameters) Distance to the available electrical substation -1 km Availability Ways of communication to the object (autoroads, Automobile gravel -

Territorial Structure of the West-Ukrainian Region Settling System

Słupskie Prace Geograficzne 8 • 2011 Vasyl Dzhaman Yuriy Fedkovych National University Chernivtsi (Ukraine) TERRITORIAL STRUCTURE OF THE WEST-UKRAINIAN REGION SETTLING SYSTEM STRUKTURA TERYTORIALNA SYSTEMU ZASIEDLENIA NA TERYTORIUM ZACHODNIEJ UKRAINY Zarys treści : W artykule podjęto próbę charakterystyki elementów struktury terytorialnej sys- temu zasiedlenia Ukrainy Zachodniej. Określono zakres organizacji przestrzennej tego systemu, uwzględniając elementy społeczno-geograficzne zachodniego makroregionu Ukrainy. Na podstawie przeprowadzonych badań należy stwierdzić, że struktura terytorialna organizacji produkcji i rozmieszczenia ludności zachodniej Ukrainy na charakter radialno-koncentryczny, co jest optymalnym wariantem kompozycji przestrzennej układu społecznego regionu. Słowa kluczowe : system zaludnienia, Ukraina Zachodnia Key words : settling system, West Ukraine Problem Statement Improvement of territorial structure of settling systems is among the major prob- lems when it regards territorial organization of social-geographic complexes. Ac- tuality of the problem is evidenced by introducing of the Territory Planning and Building Act, Ukraine, of 20 April 2000, and the General Scheme of Ukrainian Ter- ritory Planning Act, Ukraine, of 7 February 2002, both Acts establishing legal and organizational bases for planning, cultivation and provision of stable progress in in- habited localities, development of industrial, social and engineering-transport infra- structure ( Territory Planning and Building ... 2002, General Scheme of Ukrainian Territory ... 2002). Initial Premises Need for improvement of territorial organization of productive forces on specific stages of development delineates a circle of problems that require scientific research. 27 When studying problems of settling in 50-70-ies of the 20 th century, national geo- graphical science focused the majority of its attention upon separate towns and cit- ies, in particular, upon limitation of population increase in big cities, and to active growth of mid and small-sized towns. -

Cronologia Unirii Bucovinei Cu România (II): Intervenția Românească În Bucovina Și Unirea Acesteia Cu România (8-28 Noiembrie 1918)

Cronologia unirii Bucovinei cu România (II): Intervenția românească în Bucovina și unirea acesteia cu România (8-28 noiembrie 1918) Paul BRUSANOWSKI Universitatea „Lucian Blaga” din Sibiu Lucian Blaga University of Sibiu Personal e-mail: [email protected] The Chronology of Bucovina’s Union with Romania (II): The Romanian Intervention in Bucovina and its Union with Romania (8-28 November 1918) During the dissolution of Habsburg Austria, the Ukrainians organized a National Assembly in Lviv on October 19 and declared the establishment of the Ukrainian state, stretching from the San River in the west (today, in south- eastern Poland) to the Siret River in the east (thus including the northern half of Bukovina). The Romanians in Bukovina held a Constituent Assembly on October 27 and decided the unification of the whole Bukovina with Romania. On November 1, 1918, the Ukrainians organized a coup d’état and took over Eastern Galicia, and on November 6, the city of Chernivtsi. Upon the request of the Romanian Constituent Assembly, the Romanian Royal Army entered Bukovina, and on November 12, occupied the city of Chernivtsi, from which the Ukrainian soldiers and officials had fled. The Romanian National Council, established by the Constituent Assembly, took over the power in Bukovina, issued a new constitution of the country and instituted a Romanian government in Bukovina. On November 28, the Romanian government organized a Congress of all the inhabitants of Bukovina, which proclaimed the union of the province with Romania. The German and the Polish inhabitants of the province officially attended the Congress and sanctioned the union; the Jewish community boycotted the Congress, while only 13 unofficial representatives of the Ukrainian community from several Ruthenian villages participated. -

Istoria Primului Control Administrativ Al Populaţiei României Întregite Din 24 Aprilie – 5 Mai 1927

NICOLAE ENCIU* „Confidenţial şi exclusiv pentru uzul autorităţilor administrative”. ISTORIA PRIMULUI CONTROL ADMINISTRATIV AL POPULAŢIEI ROMÂNIEI ÎNTREGITE DIN 24 APRILIE – 5 MAI 1927 Abstract The present study deals with an unprecedented chapter of the demographic history of in- terwar Romania – the first administrative control of the population from 24 April to 5 May 1927. Done in the second rule of General Alexandru Averescu, the administrative control had the great merit of succeeding to determine, for the first time after the Great Union of 1918, the total number of the population of the Entire Romania, as well as the demographic dowry of the historical provinces that constituted the Romanian national unitary state. Keywords: administrative control, census, counting, total population, immigration, emigration, majority, minority, ethnic structure. 1 e-a lungul timpului, viaţa şi activitatea militarului de carieră Alexandru DAverescu (n. 9.III.1859, satul Babele, lângă Ismail, Principatele Unite, astăzi în Ucraina – †3.X.1938, Bucureşti, România), care şi-a legat numele de ma- rea epopee naţională a luptelor de la Mărăşeşti, în care s-a ilustrat Armata a 2-a, comandată de el, membru de onoare al Academiei Române (ales la 7 iunie 1923), devenit ulterior mareşal al României (14 iunie 1930), autor a 12 opere despre ches- tiuni militare, politice şi de partid, inclusiv al unui volum de memorii de pe prima linie a frontului1, a făcut obiectul mai multor studii, broşuri şi lucrări ale specialiş- tilor, pe durata întregii perioade interbelice2. * Nicolae Enciu – doctor habilitat în istorie, conferenţiar universitar, director adjunct pentru probleme de ştiinţă, Institutul de Istorie, mun. -

The Bukovina Society of the Americas NEWSLETTER

The Bukovina Society of the Americas NEWSLETTER P.O. Box 81, Ellis, KS 67637 USA March 2003 Editor: Dr. Sophie A. Welisch Board of Directors Darrell Seibel Larry Jensen e-mail: [email protected] Oren Windholz, President Martha Louise McClelland Dr. Ortfried Kotzian Web Site: www.bukovinasociety.org [email protected] Betty Younger Edward Al Lang Raymond Haneke, Vice President Paul Massier Joe Erbert, Secretary International Board Van Massirer Bernie Zerfas, Treasurer Michael Augustin Steve Parke Shirley Kroeger Dr. Ayrton Gonçalves Celestino Dr. Kurt Rein Ralph Honas Irmgard Ellingson Wilfred Uhren Ray Schoenthaler Aura Lee Furgason Dr. Sophie A. Welisch Dennis Massier Rebecca Hageman Werner Zoglauer Ralph Burns Laura Hanowski SOCIETY NEWS The board extends its sincere thanks to everyone who responded to our annual dues notice and request for donations for the web site fund. Your support is greatly appreciated. New members of the Lifetime Club Darlene E. Kauk (Regina, SK) Cheryl Runyan (Wichita, KS) Brian Schoenthaler (Calgary, AB) John Douglas Singer (New Haven, CT) Dr. Sophie A. Welisch (Congers, NY) We have received a good response from our request for presenters at the Bukovinafest 2003. Program plans are now under review and will be published in the June 2003 Newsletter. Mark the dates of September 19-21. BUKOVINA PEOPLE AND EVENTS . Our webmaster, Werner Zoglauer, received notice that our web site was named “Site of the Day” for December 9, 2002 by Family Tree Magazine, <www.familytreemagazine.com>, because “it will be a wonderful online resource for our readers.” More than 100,000 people visit the Family Tree Magazine web site each month with their weekly e-mail newsletter, which also highlights the Bukovina Society, going out to more than 30,000 subscribers. -

Crop Prices in the Austrian Monarchy (1770–1816): the Role of Crop Failures and Money Inflation

ECONOMICS AND MANAGEMENT CROP PRICES IN THE AUSTRIAN MONARCHY (1770–1816): THE ROLE OF CROP FAILURES AND MONEY INFLATION J. Blahovec Czech University of Life Sciences Prague, Faculty of Engineering, Prague, Czech Republic The paper is based on data about local cereal prices in Bohemia recorded in the course of 46 years (1770–1816) by F.J. Vavák, Czech farmer living close to Prague. This information appeared in a series of his memoirs published within 1907–1938 and in 2009. The data analysis shows that annual means of prices of wheat, rye, and barley are relatively well correlated and can be used for illustration of the state monetary situation. A higher variation of the annual mean values was observed only in times of crop failure and was also related to the new harvest. The data obtained for pea differ from the data mentioned above. It was shown that the market prices were influenced mainly by crop failures caused by weather and climate and by the state monetary policies. The money purchasing power was influenced either by objective causes, like crop failures of reversible character, or by subjective changes caused mainly by inflationary monetary policies which in the case of Austria had conduced to a state bankruptcy. cereals; market; weather; monetary policy; bankruptcy doi: 10.1515/sab-2015-0026 Received for publication on January 16, 2015 Accepted for publication on June 24, 2015 INTRODUCTION for financing a powerful army, the problem was re- solved traditionally by various methods of credit. For Austria started to change from a conservative Middle this reason, Banco dell Giro (1703) was founded, and Age country to a better, centrally managed one in the after its closing down later in 1705 it was replaced by 18th century. -

Vasyl BOTUSHANSKYY(Chernivtsi) the SOURCES of STATE

Vasyl BOTUSHANSKYY(Chernivtsi) THE SOURCES OF STATE ARCHIVES OF CHERNIVTSI REGION AS COMPONENT OF STUDIING THE EVENTS OF THE WORLD WAR I AT BUKOVYNA This article gives an overview of the sources of the State Archives of Chernivtsi region, including funds of the Austrian and Russian occupation administrations acting in Bukovina in 1914 - 1918, which recorded information about the events of World War I in the region and that can serve as sources for research of the history of these events. Keywords: Bucovina, archive, fund, information, military, troops, war, occupation, empire, requisition, refugees, internment, deportation. 1914 year - the year of the First World War, but not last, and a hundred years it was the most ambitious and bloody war, which is known to humanity, killed 10 million. People., Injuring about 20 million. The war engulfed vast areas of the world, first of all the leading countries of military-political blocs: the Triple (Germany and Austria-Hungary) and the Entente (Russia, Great Britain and France). Have covered the war and area of residence of the Ukrainian people - eastern Ukraine, which was part of the Russian Empire and the West in the empire of Austria-Hungary, including Galicia and Bukovina. Ukrainian tragedy of this war was that mobilized in the opposite army, they were forced to kill each other. Coverage of the history of World War II Ukrainian lands, including and Bukovina, has dedicated many works, and this research continues. Of course, they would have been impossible without the historical sources. For the sake of objectivity it should be recognized that archaeography Bukovina already has on this issue considerable achievements, but many more sources should be identified and investigated. -

Jewish Cemetries, Synagogues, and Mass Grave Sites in Ukraine

Syracuse University SURFACE Religion College of Arts and Sciences 2005 Jewish Cemetries, Synagogues, and Mass Grave Sites in Ukraine Samuel D. Gruber United States Commission for the Preservation of America’s Heritage Abroad Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/rel Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Gruber, Samuel D., "Jewish Cemeteries, Synagogues, and Mass Grave Sites in Ukraine" (2005). Full list of publications from School of Architecture. Paper 94. http://surface.syr.edu/arc/94 This Report is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts and Sciences at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Religion by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. JEWISH CEMETERIES, SYNAGOGUES, AND MASS GRAVE SITES IN UKRAINE United States Commission for the Preservation of America’s Heritage Abroad 2005 UNITED STATES COMMISSION FOR THE PRESERVATION OF AMERICA’S HERITAGE ABROAD Warren L. Miller, Chairman McLean, VA Members: Ned Bandler August B. Pust Bridgewater, CT Euclid, OH Chaskel Besser Menno Ratzker New York, NY Monsey, NY Amy S. Epstein Harriet Rotter Pinellas Park, FL Bingham Farms, MI Edgar Gluck Lee Seeman Brooklyn, NY Great Neck, NY Phyllis Kaminsky Steven E. Some Potomac, MD Princeton, NJ Zvi Kestenbaum Irving Stolberg Brooklyn, NY New Haven, CT Daniel Lapin Ari Storch Mercer Island, WA Potomac, MD Gary J. Lavine Staff: Fayetteville, NY Jeffrey L. Farrow Michael B. Levy Executive Director Washington, DC Samuel Gruber Rachmiel -

Proquest Dissertations

LITERATURE, MODERNITY, NATION THE CASE OF ROMANIA, 1829-1890 Alexander Drace-Francis School of Slavonic and East European Studies, University College London Thesis submitted for the degree of PhD June, 2001 ProQuest Number: U642911 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest. ProQuest U642911 Published by ProQuest LLC(2016). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 ABSTRACT The subject of this thesis is the development of a literary culture among the Romanians in the period 1829-1890; the effect of this development on the Romanians’ drive towards social modernization and political independence; and the way in which the idea of literature (as both concept and concrete manifestation) and the idea of the Romanian nation shaped each other. I concentrate on developments in the Principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia (which united in 1859, later to form the old Kingdom of Romania). I begin with an outline of general social and political change in the Principalities in the period to 1829, followed by an analysis of the image of the Romanians in European public opinion, with particular reference to the state of cultural institutions (literacy, literary activity, education, publishing, individual groups) and their evaluation for political purposes. -

Eugen Ehrlich's ›Living Law‹ and the Use of Civil Justice in The

ADMINISTORY ZEITSCHRIFT FÜR VERWALTUNGSGESCHICHTE BAND 5, 2020 SEITE 235–248 D O I : 10.2478/ADHI-2020-0015 Litigious Bukovina: Eugen Ehrlich’s ›Living Law‹ and the Use of Civil Justice in the Late Habsburg Monarchy WALTER FUCHS Ehrlich’s Living Law as a Concept of Multi-normativity of the traditional direction would undoubtedly claim The Austrian jurist Eugen Ehrlich (1862–1922) is that all these peoples have only one, and exactly considered not only one of the founders of the sociology the same, Austrian law, which is valid throughout of law but also a pioneer of legal pluralism. As a matter Austria. And yet even a cursory glance could convince of fact, he conceptually and empirically analysed him that each of these tribes observes quite different the coexistence of different normative orders within legal rules in all legal relations of daily life. […] I have one and the same society. Ehrlich was born the son decided to survey the living law of the nine tribes of of a Jewish lawyer in Czernowitz,1 then capital of the the Bukovina in my seminar for living law. 5 Bukovina, a crown land of the Habsburg Empire at its eastern periphery, where he later worked as professor Ehrlich coined the term living law for these »quite of Roman law.2 Like the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy different« norms that are actually relevant to everyday itself – against whose dissolution Ehrlich passionately action. As he theoretically outlined in his monograph argued for pacifist reasons at the end of the First World »Fundamental Principles of the Sociology of Law«, -

Academy of Romanian Scientists Series on History and Archaeology ISSN 2067-5682 Volume 10, Number 1/2018 5

Annals of the Academy of Romanian Scientists Series on History and Archaeology ISSN 2067-5682 Volume 10, Number 1/2018 5 THE RETURN OF BESSARABIA WITHIN THE BOUNDARIES OF THE COUNTRY – INTERNAL AND EXTERNAL CONDITIONS Corneliu-Mihail LUNGU Abstract. Given that over the time, a great deal has been written - fully justified - about Bessarabia’s history, I considered that there is no need to approach again some of the aspects that are too well known and dealt with scientific probity by those who dared to. We wanted to use the memory of other documents - especially those preserved in foreign archives - in order to outline, in the first place, the very special internal and external conditions in which the return of Bessarabia to Romania was made. Another aim is to demonstrate that the only ones who wanted the unity and fought for this purpose were just the Romanians, without any type of support from anyone, but obstacles and barriers. Keywords: Bessarabia, Romania, Tsarist Russia, 1812, Prut, Nistru In 1812, 200 years since the annexation of Bessarabia by Tsarist Russia, I published a study1 based on archive documents demonstrating that the act was intentional and possible due to the agreement of other great powers. Now, a century after the territory between Prut and Nistru returned in the natural boundaries of the Country, I considered appropriate, based on other documentary testimonies, to mark the event that opened both the way to fulfilling the national ideal and the completion of the process of Romania’s unification that started in 1859. Given that over the time, a great deal has been written - fully justified - about Bessarabia’s history, I considered that there is no need to approach again some of the aspects that are too well known and dealt with scientific probity by those who dared to.