A New Account of George Shell and the Newport Rising

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

X24 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

X24 bus time schedule & line map X24 Blaenavon - Newport View In Website Mode The X24 bus line (Blaenavon - Newport) has 5 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Blaenavon: 6:22 AM - 8:20 PM (2) Cwmbran: 6:02 PM - 7:02 PM (3) Cwmbran: 6:00 PM - 9:15 PM (4) Newport: 6:00 AM - 8:15 PM (5) Varteg: 9:20 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest X24 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next X24 bus arriving. Direction: Blaenavon X24 bus Time Schedule 42 stops Blaenavon Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 9:15 AM - 6:00 PM Monday 6:22 AM - 8:20 PM Market Square 16, Newport Tuesday 6:22 AM - 8:20 PM Llanyravon Boating Lake, Llanyrafon Wednesday 6:22 AM - 8:20 PM Llanyravon Square, Llanyrafon Thursday 6:22 AM - 8:20 PM Llan-yr-avon Square, Llanyrafon Community Friday 6:22 AM - 8:20 PM Redbrook House, Southville Saturday 6:22 AM - 8:20 PM Llantarnam Grange, Cwmbran Bus Station E, Cwmbran Gwent Square, Cwmbran X24 bus Info Llantarnam Grange, Cwmbran Direction: Blaenavon Stops: 42 Trussel Road, Northville Trip Duration: 58 min St David's Road, Cwmbran Line Summary: Market Square 16, Newport, Llanyravon Boating Lake, Llanyrafon, Llanyravon Ebenezer, Northville Square, Llanyrafon, Redbrook House, Southville, Llantarnam Grange, Cwmbran, Bus Station E, Avondale Close, Pontrhydyrun Cwmbran, Llantarnam Grange, Cwmbran, Trussel Road, Northville, Ebenezer, Northville, Avondale Avondale Close, Cwmbran Close, Pontrhydyrun, Ashbridge, Pontrhydyrun, Parc Ashbridge, Pontrhydyrun Panteg, Pontrhydyrun, South Street, Sebastopol, -

Chartist Newsletter 4

No 4 March 2014 Celebrating the Chartists NEWSLETTER THE 175TH ANNIVERSARY ROLLS OUT ACROSS THE REGION Newport City Council sets up ALSO in this EDITION: Chartist Commission: 4 A Dame, ex-Archbishop and retired NEW FEATURE starts this month! DIGITAL Teacher appointed CHARTISM SOURCES page 6 The Council is keen to make 2014 a How to search the ‘Northern Star’ - also ‘celebration of Chartism’ and will support the commission in its work’, announced Councillor excerpts from the ‘Western Vindicator’ Bob Bright, Leader of Newport Council BOOK of the MONTH: Voices for the Vote Shire Hall at Monmouth plans video (Shire Hall publication 2011) page 3 link with Tasmania 8 In our February edition, we boasted ONE HUNDRED & SEVENTY FIVE YEARS that we intended to reach the parts AGO During March 1839, Henry Vincent on “where Frost & Co were banished”. Tour From Bristol to Monmouth page 7 Gwent Archives starts activities in March 20th Vincent takes tea with the the Gwent Valleys. Rhondda LHS Chartist Ladies at Newport page 11 9 supporting ‘Chartist Day School’ at Pontypridd WHAT’s in NEWPORT MUSEUM? Two Silver CHARTIST HERITAGE rescued Cups for a loyal power broker page 2 at Merthyr – Vulcan House 10 restored and our NETWORKING pages 10 & 11 Before After Vulcan House, Morganstown in Merthyr Tydfil, - Now 1 WHAT’s in NEWPORT MUSEUM? SILVER CUPS PRESENTED TO THOMAS PHILLIPS Silver cup with profuse vine clusters, cover with figure finial, Silver cup with inscribed lid “presented by Benj Hall Esq., inscribed as presented “by the Committee for Conducting MP of llanover to Thomas Phillips Esq.,Jnr., as a testimony the Election for William Adams Williams Esq MP 1831” of the high estimation he entertains of his talents and of the great professional knowledge and ability WHICH HE SO DISINTERESTEDLY AND PERSERVERINGLY EXERTED FOR THE GOOD OF HIS COUNTRY during the arduous contest FOR THE UNITED BOROUGHS OF MONMOUTH, NEWPORT, AND USK, IN 1831 & FIDUS ET FIRMUS” Received for political services was usually settled without contest. -

(Public Pack)Agenda Document for Cabinet, 19/07/2017 16:00

Public Document Pack Agenda Cabinet Date: Wednesday, 19 July 2017 Time: 4.00 pm Venue: Committee Room 1 - Civic Centre To: Councillors D Wilcox (Chair), P Cockeram, G Giles, D Harvey, R Jeavons, D Mayer, J Mudd, R Truman and M Whitcutt Item Wards Affected 1 Apologies for Absence 2 Agenda yn Gymraeg (Pages 3 - 4) 3 Declarations of Interest 4 Minutes of the Last Meeting (Pages 5 - 10) 5 Sale of Friars Walk (Pages 11 - 24) Stow Hill 6 Director of Social Services Annual Report (Pages 25 - 78) All Wards 7 City of Democracy (Pages 79 - 118) All Wards 8 Newport Economic Network (Pages 119 - 126) All Wards 9 Wales Audit Office Action Plan (Pages 127 - 148) All Wards 10 Budget Consultation and Engagement Process (Pages 149 - 160) All Wards 11 Medium Term Financial Plan (Pages 161 - 186) All Wards 12 Revenue Budget Monitor (Pages 187 - 204) All Wards 13 21st Century Schools (Pages 205 - 226) All Wards 14 Cabinet Work Programme (Pages 227 - 232) Contact: Eleanor Mulligan, Head of Democratic Services (Interim) Tel: 01633 656656 E-mail: [email protected] Date of Issue: 12 July 2017 This page is intentionally left blank Agenda Item 2 Agenda Cabinet Dyddiad: Dydd Mercher, 19 Gorffennaf 2017 Amser: 4 y.p. Lleoliad: Ystafell Bwyllgor 1 – Y Ganolfan Ddinesig At: Cynghorwyr: D Wilcox (Cadeirydd), P Cockeram, G Giles, D Harvey, R Jeavons, D Mayer, J Mudd, R Truman a M Whitcutt Eitem Wardiau Dan Sylw 1 Agenda yn Gymraeg 2 Ymddiheuriadau am absenoldeb 3 Datganiadau o fuddiant 4 Cofnodion 5 Gwerthu Friars Walk 6 Adroddiad Blynyddol y Cyfarwyddwr -

Wales Would Have to Invent Them

Celebrating Democracy Our Voice, Our Vote, Our Freedom 170th anniversary of the Chartist Uprising in Newport. Thursday 15 October 2009 at The Newport Centre exciting opportunities ahead. We stand ready to take on bad Introduction from Paul O’Shea employers, fight exploitation and press for social justice with a clear sense of purpose. Chair of Bevan Foundation and Regional Let us put it this way, if unions did not exist today, someone Secretary , Unison Cymru / Wales would have to invent them. Employers need to talk to employees, Freedom of association is rightly prominent in every charter government needs views from the workplace and above all, and declaration of human rights. It is no coincidence that employees need a collective voice. That remains as true today, as authoritarians and dictators of left and right usually crack down it was in Newport, in November 1839. on trade unions as a priority. Look to the vicious attacks on the union movement by the Mugabe regime, the human rights abuses of Colombian trade unionists or indeed, the shooting and Electoral Reform Society incarceration of Chartists engaged in peaceful protest as a grim reminder of this eternal truth. The Electoral Reform Society is proud to support this event commemorating 170 years since the Newport Rising. The ERS A free and democratic society needs to be pluralist. There must campaigns on the need to change the voting system to a form of be checks and balances on those who wield power. There must proportional representation, and is also an active supporter Votes be a voice for everyone, not just the rich, the privileged and at 16 and involved in producing materials for the citizenship the powerful. -

The Blaenavon Ironmasters

THE BLAENAVON IRONMASTERS The industrial revolution would never have occurred if it were not for the risks and innovation of entrepreneurs. In south Wales, during the late eighteenth century, ironmasters set up a string of new ironworks, making the region the most important iron-producing region in the world. The labouring classes undeniably played a hugely significant role in the industrialisation process but it was the capital and experience of businessmen that made the industrial revolution a success. This article examines the history of the Blaenavon ironmasters and how they used their experience and their influence to create the town of Blaenavon. The Experience of the Blaenavon Ironmasters The leases for the area of Blaenavon, known as ‘Lord Abergavenny’s Hills’, were not renewed during the 1780s. The West Midlands industrialist, Thomas Hill (1736-1824), and his partners, Thomas Hopkins (d.1793) and Benjamin Pratt (1742-1794), seized the opportunity to invest in the Blaenavon site, which they knew was rich in mineral resources. The businessmen invested some £40,000 into the ironworks project and erected three blast furnaces. It was an incredibly risky venture but the three men were confident that the enterprise would be a large-scale success and that their investment would provide considerable returns. The experience that all three men had acquired in iron-making, business and banking, proved invaluable in numerous ways. Family Background Thomas Hill, the leading partner, came from a very wealthy industrial background. He was a successful Worcestershire banker and ran Wollaston slitting mill. Hill had also inherited a considerable fortune from his father, Waldron Hill (1706-88), and his uncle, Thomas Hill (1711-82), who were successful glassmakers at Coalbournhill, Stourbridge. -

Highway Asset Management Plan 2019-2025

TORFAEN COUNTY BOROUGH COUNCIL HIGHWAY ASSET MANAGEMENT PLAN 2019 – 2025 Setting the Standard This set of documents outlines the methods and specifications for the recording and maintenance of all highway assets and has been divided into the following sections: Section 1: Highway Asset Management Policy for the Adopted Highway Section 2: Highway Asset Management Strategy for the Adopted Highway Section 3: Highway Asset Data Management Plan for the Adopted Highway Section 4: Highway Asset Maintenance Manual for the Adopted Highway Section 5: Risk Based Approach Methodology for the Adopted Highway Section 6: Highway Drainage Cleansing Service for the Adopted Highway Section 7: Skid Resistance Policy for the Adopted Highway Section 1 TORFAEN COUNTY BOROUGH COUNCIL HIGHWAY ASSET MANAGEMENT POLICY FOR THE ADOPTED HIGHWAY 2019 TO 2025 Date March 2019 Author Mark Strickland Issued to Version No 2 .3 1 Introduction 1.1 The over-riding asset management policy for the Authority was agreed by Cabinet on 24 February 2009. It states: “That the Council will only retain or acquire properties that are sufficient, suitable and sustainable in the delivery of its corporate plan priorities and will prioritise the use of its capital and revenue budgets accordingly. Property resources that are surplus to, unsuitable or unsustainable in the delivery of Corporate Plan priorities will be considered for disposal at best consideration”. 1.2 Whilst this policy relates to Council owned buildings and land it is deemed appropriate and good practice to include the highway assets that Torfaen County Borough Council maintain in its role as a Highway Authority. To ensure that the Council apply the same principles to both assets the following Highway Asset Management Policy is to be placed before the Torfaen County Borough Council Cabinet in 2019. -

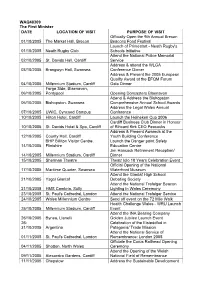

WAQ48309 the First Minister DATE LOCATION OF

WAQ48309 The First Minister DATE LOCATION OF VISIT PURPOSE OF VISIT Officially Open the 9th Annual Brecon 01/10/2005 The Market Hall, Brecon Beacons Food Festival Launch of Primestart - Neath Rugby's 01/10/2005 Neath Rugby Club Schools Initiative Attend the National Police Memorial 02/10/2005 St. Davids Hall, Cardiff Service Address & attend the WLGA 03/10/2005 Brangwyn Hall, Swansea Conference Dinner Address & Present the 2005 European Quality Award at the EFQM Forum 04/10/2005 Millennium Stadium, Cardiff Gala Dinner Forge Side, Blaenavon, 06/10/2005 Pontypool Opening Doncasters Blaenavon Attend & Address the Bishopston 06/10/2005 Bishopston, Swansea Comprehensive Annual School Awards Address the Legal Wales Annual 07/10/2005 UWIC, Cyncoed Campus Conference 10/10/2005 Hilton Hotel, Cardiff Launch the Heineken Cup 2006 Cardiff Business Club Dinner in Honour 10/10/2005 St. Davids Hotel & Spa, Cardiff of Rihcard Kirk CEO Peacocks Address & Present Awareds at the 12/10/2005 County Hall, Cardiff Youth Building Conference BHP Billiton Visitor Centre, Launch the Danger point Safety 14/10/2005 Flintshire Education Centre Jim Hancock Retirement Reception/ 14/10/2005 Millennium Stadium, Cardiff Dinner 15/10/2005 Sherman Theatre Theatr Iolo 18 Years Celebration Event Official Opening of the National 17/10/2005 Maritime Quarter, Swansea Waterfront Museum Attend the Glantaf High School 21/10/2005 Ysgol Glantaf Debating Society Attend the National Trafalgar Beacon 21/10/2005 HMS Cambria, Sully Lighting in Wales Ceremony 23/10/2005 St. Paul's Cathedral, London Attend the National Trafalgar Service 24/10/2005 Wales Millennium Centre Send off event on the 72 Mile Walk Health Challenge Wales - WRU Launch 25/10/2005 Millennium Stadium, Cardiff Event Attend the INA Bearing Company 26/10/2005 Bynea, Llanelli Golden Jubilee Launch Event 26- Celebration of the Eisteddfod in 31/10/2005 Argentina Patagonia/ Trade Mission Attend the National Service of 01/11/2005 St. -

The Old New Journalism?

ORBIT-OnlineRepository ofBirkbeckInstitutionalTheses Enabling Open Access to Birkbeck’s Research Degree output The development and impact of campaigning journal- ism in Britain, 1840-1875 : the old new journalism? https://eprints.bbk.ac.uk/id/eprint/40128/ Version: Full Version Citation: Score, Melissa Jean (2015) The development and impact of campaigning journalism in Britain, 1840-1875 : the old new journalism? [Thesis] (Unpublished) c 2020 The Author(s) All material available through ORBIT is protected by intellectual property law, including copy- right law. Any use made of the contents should comply with the relevant law. Deposit Guide Contact: email Birkbeck, University of London The Development and Impact of Campaigning Journalism in Britain, 1840–1875: The Old New Journalism? Melissa Jean Score Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy November 2014 2 Declaration I, Melissa Jean Score, declare that this thesis is all my own work. Signed declaration_________________________________________ Date_____________________ 3 Abstract This thesis examines the development of campaigning writing in newspapers and periodicals between 1840 and 1875 and its relationship to concepts of Old and New Journalism. Campaigning is often regarded as characteristic of the New Journalism of the fin de siècle, particularly in the form associated with W. T. Stead at the Pall Mall Gazette in the 1880s. New Journalism was persuasive, opinionated, and sensational. It displayed characteristics of the American mass-circulation press, including eye-catching headlines on newspaper front pages. The period covered by this thesis begins in 1840, with the Chartist Northern Star as the hub of a campaign on behalf of the leaders of the Newport rising of November 1839. -

Blaenavon Management Plan

Nomination of the BLAENAVON INDUSTRIAL LANDSCAPE for inclusion in the WORLD HERITAGE LIST WORLD HERITAGE SITE MANAGEMENT PLAN Management Plan for the Nominated World Heritage Site of BLAENAVON INDUSTRIAL LANDSCAPE Version 1.2 October 1999 Prepared by THE BLAENAVON PARTNERSHIP TORFAEN BWRDEISTREF COUNTY SIROL BOROUGH TORFAEN Torfaen County Borough Council British Waterways Wales Tourist Royal Commission on the Ancient Blaenau Gwent County Monmouthshire Countryside Council CADW Board Board & Historical Monuments of Wales Borough Council County Council for Wales AMGUEDDFEYDD AC ORIELAU CENEDLAETHOL CYMRU NATIONAL MUSEUMS & GALLERIES OF WALES National Brecon Beacons Welsh Development Blaenavon National Museums & Galleries of Wales Trust National Park Agency Town Council For Further Information Contact John Rodger Blaenavon Co-ordinating Officer Tel: +44(0)1633 648317 c/o Development Department Fax:+44(0)1633 648088 Torfaen County Borough Council County Hall, CWMBRAN NP44 2WN e-mail:[email protected] Nomination of the BLAENAVON INDUSTRIAL LANDSCAPE for the inclusion in the WORLD HERITAGE LIST We as representatives of the Blaenavon Partnership append our signatures as confirmation of our support for the Blaenavon Industrial Landscape Management Plan TORFAEN BWRDEISTREF COUNTY SIROL BOROUGH TORFAEN Torfaen County Borough Council Monmouthshire Blaenau Gwent County County Council Borough Council Brecon Beacons Blaenavon National Park Town Council Royal Commission on the Ancient CADW & Historical Monuments of Wales AMGUEDDFEYDD AC ORIELAU -

Popular Political Oratory and Itinerant Lecturing in Yorkshire and the North East in the Age of Chartism, 1837-60 Janette Lisa M

Popular political oratory and itinerant lecturing in Yorkshire and the North East in the age of Chartism, 1837-60 Janette Lisa Martin This thesis is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of York Department of History January 2010 ABSTRACT Itinerant lecturers declaiming upon free trade, Chartism, temperance, or anti- slavery could be heard in market places and halls across the country during the years 1837- 60. The power of the spoken word was such that all major pressure groups employed lecturers and sent them on extensive tours. Print historians tend to overplay the importance of newspapers and tracts in disseminating political ideas and forming public opinion. This thesis demonstrates the importance of older, traditional forms of communication. Inert printed pages were no match for charismatic oratory. Combining personal magnetism, drama and immediacy, the itinerant lecturer was the most effective medium through which to reach those with limited access to books, newspapers or national political culture. Orators crucially united their dispersed audiences in national struggles for reform, fomenting discussion and coalescing political opinion, while railways, the telegraph and expanding press reportage allowed speakers and their arguments to circulate rapidly. Understanding of political oratory and public meetings has been skewed by over- emphasis upon the hustings and high-profile politicians. This has generated two misconceptions: that political meetings were generally rowdy and that a golden age of political oratory was secured only through Gladstone’s legendary stumping tours. However, this thesis argues that, far from being disorderly, public meetings were carefully regulated and controlled offering disenfranchised males a genuine democratic space for political discussion. -

Newport-LDP Employment Paper Final

Final Report Newport LDP 2011-2016 Employment Context Paper March 2011 Churchill House, Churchill Way, Cardiff, CF10 2HH 02920 353400 www.aecom.com/designplanning Newport Local Development Plan 2011-2026 Employment Context Paper CONTENTS 1. Introduction 1 2. Macro Economic Outlook 2 3. The Recession in Wales 6 4. Newport Economic Context 8 5. Newport Future Trends 13 6. Employment Land Needs 14 7. Land & Property Supply 19 8. Supply & Demand Compared 22 9. Summary & Conclusions 24 Appendix 1 Employment Sites – Classification & Availability Final Report March 2011 Newport Local Development Plan 2011-2026 Employment Context Paper 1. INTRODUCTION Newport is a strategically important, gateway city to south east Wales. With a long history of economic development and growth, the city has evolved from an historic port, major steel producing and manufacturing town and is beginning to emerge as a dynamic service economy. The Vision for Newport is for “a focus for diverse economic growth that will strengthen its contribution to the region” and sees Newport being recognised as “a lively, dynamic growing city”. (Newport LDP Preferred Strategy: January 2010). Much has already been achieved to restructure the local economy and help realise the city’s growth potential. The city has not been immune, however, to the effects of the recent global economic recession and must again position itself effectively to the new economic climate and emerging challenges. This document has been prepared by AECOM on behalf of Newport City Council and provides the economic context for future employment land requirements for the LDP 2011-2016. The document reflects on the macro-economic conditions in a post recessionary UK and considers the implications for Wales generally and Newport in particular in light of the new environment. -

The Pontypool Deep Place Study

All Around Us The Pontypool Deep Place Study Dr Mark Lang 2016 Contents Page Executive Summary 3 1.0 Introduction 5 2.0 Theoretical Influences 7 2.1 Social Exclusion 9 2.2 Transition Theory 10 2.3 Total Place 11 2.4 Foundational Economy 12 3.0 Legislative Context 13 3.1 Well-being of Future Generations Act 13 3.2 Environment Act 15 3.3 Planning Act 16 4.0 Economic Context 16 4.1 The Context for Economic Policy Making in Wales 16 4.2 Welsh Economic Policy 18 5.0 Methodology 20 5.1 Selecting the Place 20 5.2 A Brief History of Pontypool 21 5.3 Methodology 23 5.4 Research Methods 23 6.0 Re-Localising Economic Activity 24 6.1 Torfaen Economic Approach 26 6.2 Tourism 28 6.3 Pontypool Town Centre 29 7.0 The Local Economic Sectors 39 7.1 Food 40 7.2 Energy and Energy Efficiency 43 7.3 Care 47 7.4 Environment 48 7.5 E-commerce and Employment 50 8.0 Breaking Down the Challenges 51 8.1 Health 54 8.2 Education and Skills 59 8.3 Housing 63 8.4 Transport 68 9.0 Conclusions 70 References 72 Appendix 1: List of Think Space Attendees 86 Appendix 2: List of Action Points 88 2 Executive Summary Undertaken with support from the Sustainable Places Research Institute at Cardiff University, this report sets out and further develops the Deep Place approach to sustainable place- making advocated in the Tredegar Study of 2014, and which has now been further applied in Pontypool.