Mother Earth. It Will Surely Prove Interesting Reading

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter Five Publishing the Private, Or the Economics of Experience

Chapter Five Publishing the Private, or The Economics of Experience Sometimes it has occurred to me that a man should not live more than he can record, as a farmer should not have a larger crop than he can gather in. – Boswell: The Hypochondriack Though the earth and all inferior creatures be common to all men, yet every man has a property in his own person; this nobody has any right to but himself – Locke: Second Treatise on Civil Government I In a finely tempered and persuasive record of her encounters with Strindberg in Switzerland in 1884, Hélène Welinder recalls a conversation in which his young compatriot’s sympathetic concern prompted the tired and harassed writer to describe the condition of almost permanent literary production in which he lived with unusual clarity. ‘I cannot rest, even if I would like to,’ he is reported as saying: I have to write for my daily bread, to maintain my wife and children, and in other respects, too, I cannot leave it alone. If I am travelling by train or whatever I’m doing, my mind works without ceasing, it grinds and grinds like a mill, and I cannot stop it. I get no peace before I have put it down on paper, but then I begin all over again, and so the misery goes on.1 Whether or not the image of the remorseless and insatiable mill reached this quotation as a direct transcription of Strindberg’s words is, of course, open to question. Nevertheless, even if it belongs entirely to Welinder’s reconstruction, it is apposite, for it not only features frequently in Strindberg’s later work as an image for the treadmill of conscience and the tenacity with which the past clings to the present;2 it also encompasses the suggestion that to write out what experience provides affords at best only temporary relief. -

Anarchy! an Anthology of Emma Goldman's Mother Earth

U.S. $22.95 Political Science anarchy ! Anarchy! An Anthology of Emma Goldman’s MOTHER EARTH (1906–1918) is the first An A n t hol o g y collection of work drawn from the pages of the foremost anarchist journal published in America—provocative writings by Goldman, Margaret Sanger, Peter Kropotkin, Alexander Berkman, and dozens of other radical thinkers of the early twentieth cen- tury. For this expanded edition, editor Peter Glassgold contributes a new preface that offers historical grounding to many of today’s political movements, from liber- tarianism on the right to Occupy! actions on the left, as well as adding a substantial section, “The Trial and Conviction of Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman,” which includes a transcription of their eloquent and moving self-defense prior to their imprisonment and deportation on trumped-up charges of wartime espionage. of E m m A g ol dm A n’s Mot h er ea rt h “An indispensable book . a judicious, lively, and enlightening work.” —Paul Avrich, author of Anarchist Voices “Peter Glassgold has done a great service to the activist spirit by returning to print Mother Earth’s often stirring, always illuminating essays.” —Alix Kates Shulman, author of Memoirs of an Ex-Prom Queen “It is wonderful to have this collection of pieces from the days when anarchism was an ism— and so heady a brew that the government had to resort to illegal repression to squelch it. What’s more, it is still a heady brew.” —Kirkpatrick Sale, author of The Dwellers in the Land “Glassgold opens with an excellent brief history of the publication. -

Strindberg on International Stages/ Strindberg in Translation

Strindberg on International Stages/ Strindberg in Translation Strindberg on International Stages/ Strindberg in Translation Edited by Roland Lysell Strindberg on International Stages/Strindberg in Translation, Edited by Roland Lysell This book first published 2014 Cambridge Scholars Publishing 12 Back Chapman Street, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2XX, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2014 by Roland Lysell and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-5440-9, ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-5440-5 CONTENTS Contributors ............................................................................................... vii Introduction ................................................................................................. 1 Section I The Theatrical Ideas of August Strindberg Reflected in His Plays ........... 11 Katerina Petrovska–Kuzmanova Stockholm University Strindberg Corpus: Content and Possibilities ........ 21 Kristina Nilsson Björkenstam, Sofia Gustafsson-Vapková and Mats Wirén The Legacy of Strindberg Translations: Le Plaidoyer d'un fou as a Case in Point ....................................................................................... 41 Alexander Künzli and Gunnel Engwall Metatheatrical -

The Son of a Servant

THE SON OF A SERVANT BY AUGUST STRINDBERG AUTHOR OF "THE INFERNO," "ZONES OF THE SPIRIT," ETC. TRANSLATED BY CLAUD FIELD WITH AN INTRODUCTION BY HENRY VACHER-BURCH G.P. PUTNAM'S SONS NEW YORK AND LONDON The Knickerbocker Press 1913 CONTENTS I. FEAR AND HUNGER II. BREAKING-IN III. AWAY FROM HOME IV. INTERCOURSE WITH THE LOWER CLASSES V. CONTACT WITH THE UPPER CLASSES VI. THE SCHOOL OF THE CROSS VII. FIRST LOVE VIII. THE SPRING THAW IX. WITH STRANGERS X. CHARACTER AND DESTINY AUGUST STRINDBERG AS NOVELIST From the Publication of "The Son of a Servant" to "The Inferno" (1886-1896) A celebrated statesman is said to have described the biography of a cardinal as being like the Judgment Day. In reading August Strindberg's autobiographical writings, as, for example, his Inferno, and the book for which this study is a preface, we must remember that he portrays his own Judgment Day. And as his works have come but lately before the great British public, it may be well to consider what attitude should be adopted towards the amazing candour of his self-revelation. In most provinces of life other than the comprehension of our fellows, the art of understanding is making great progress. We comprehend new phenomena without the old strain upon our capacity for readjusting our point of view. But do we equally well understand our fellow-being whose way of life is not ours? We are patient towards new phases of philosophy, new discoveries in science, new sociological facts, observed in other lands; but in considering an abnormal type of man or woman, hasty judgment or a too contracted outlook is still liable to cloud the judgment. -

Herald of the Future? Emma Goldman, Friedrich Nietzsche and the Anarchist As Superman

The University of Manchester Research Herald of the future? Emma Goldman, Friedrich Nietzsche and the anarchist as superman Document Version Accepted author manuscript Link to publication record in Manchester Research Explorer Citation for published version (APA): Morgan, K. (2009). Herald of the future? Emma Goldman, Friedrich Nietzsche and the anarchist as superman. Anarchist Studies, 17(2), 55-80. Published in: Anarchist Studies Citing this paper Please note that where the full-text provided on Manchester Research Explorer is the Author Accepted Manuscript or Proof version this may differ from the final Published version. If citing, it is advised that you check and use the publisher's definitive version. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the Research Explorer are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Takedown policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please refer to the University of Manchester’s Takedown Procedures [http://man.ac.uk/04Y6Bo] or contact [email protected] providing relevant details, so we can investigate your claim. Download date:04. Oct. 2021 Herald of the future? Emma Goldman, Friedrich Nietzsche and the anarchist as superman Kevin Morgan In its heyday around the turn of the twentieth century, Emma Goldman more than anybody personified anarchism for the American public. Journalists described her as anarchy’s ‘red queen’ or ‘high priestess’. At least one anarchist critic was heard to mutter of a ‘cult of personality’.1 Twice, in 1892 and 1901, Goldman was linked in the public mind with the attentats or attempted assassinations that were the movement’s greatest advertisement. -

Sholem Schwarzbard: Biography of a Jewish Assassin

Sholem Schwarzbard: Biography of a Jewish Assassin The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Johnson, Kelly. 2012. Sholem Schwarzbard: Biography of a Jewish Assassin. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:9830349 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA © 2012 Kelly Scott Johnson All rights reserved Professor Ruth R. Wisse Kelly Scott Johnson Sholem Schwarzbard: Biography of a Jewish Assassin Abstract The thesis represents the first complete academic biography of a Jewish clockmaker, warrior poet and Anarchist named Sholem Schwarzbard. Schwarzbard's experience was both typical and unique for a Jewish man of his era. It included four immigrations, two revolutions, numerous pogroms, a world war and, far less commonly, an assassination. The latter gained him fleeting international fame in 1926, when he killed the Ukrainian nationalist leader Symon Petliura in Paris in retribution for pogroms perpetrated during the Russian Civil War (1917-20). After a contentious trial, a French jury was sufficiently convinced both of Schwarzbard's sincerity as an avenger, and of Petliura's responsibility for the actions of his armies, to acquit him on all counts. Mostly forgotten by the rest of the world, the assassin has remained a divisive figure in Jewish-Ukrainian relations, leading to distorted and reductive descriptions his life. -

'I'm a Devilish Fellow Who Can Do Many Tricks'

FACTS ABOUT SWEDEN | AUGUST STRINDBERG sweden.se P P H H O O T T O: O: S N T ORDI RIND S B K ER A MU GS MU S EE S T EE T August Strindberg: self-portrait from Gersau, Switzerland, 1886. Jealousy Night, painted by Strindberg in Berlin, Germany, 1893. AUGUST STRINDBERG: ‘I’M A DEVILISH FELLOW WHO CAN DO MANY TRICKS’ A hundred years after his death, August Strindberg (1849–1912) continues to fascinate. He was a trailblazer and innovator in his time and still manages to provoke audiences in theaters around the world. There is always an aspect of Strindberg’s everyday language, and today his texts led. His literary development largely fol- character – from the raging sociopoliti- feel remarkably modern. lowed the twists and turns of his private cal polemicist to the psychologically life, including the crises arising from his introspective writer – that fits the prevail- Man of many talents marriage break-ups and political contro- ing spirit and intellectual climate of the People are amazed by Strindberg’s ver- versies. times. His thoughts on morality, class, satility. He tackled most genres. Aside power structures and familial politics from being an innovator in drama and Upbringing and studies are still relevant today. The unflagging prose, he was a poet, a painter, a pho- Johan August Strindberg was born on struggle for free thinking and free speech tographer, even a sinologist. 22 January 1849. He would later claim that he waged throughout his life is more Strindberg’s stormy private life also that his childhood was one of poverty important than ever in a time when cen- explains his enduring appeal, especially and neglect but the family was not poor. -

Novels/Fiction

NOVELS/FICTION Achebe, Chinua Things Fall Apart F ACH:C Also available as an eBook. Okonkwo, a member of the Ibo tribe in Nigeria at the end of the last century, is a man of power and substance. He reveres his family ancestors and gods and unquestioningly upholds the laws of the tribe. Adichie, Chimamanda Half of a Yellow Sun F ADI:C Set in Nigeria during the 1960s, at the time of a vicious civil war in which a million people died and thousands were massacred in cold blood. The three main characters in the novel are swept up in the violence during these turbulent years. Adichie, Chimamanda Ngozi Americanah : a Novel F ADI:C As teenagers in Lagos, Ifemelu and Obinze fall in love. Their Nigeria is under military dictatorship, and people are fleeing the country if they can. Adiga, Aravind The White Tiger F ADI:A Also available as an eBook. Meet Balram Halwai, the `White Tiger': servant, philosopher, entrepreneur and murderer. Born in a village in the dark heart of India, the son of a rickshaw puller, Balram is taken out of school by his family and put to work in a teashop. As he crushes coal and wipe tables, he nurses a dream of escape. Adiga, Aravind Between the Assassinations F ADI:A An illiterate Muslim boy working at the train station finds himself tempted by an Islamic terrorist; a bookseller is arrested for selling a copy of The Satanic Verses; a rich, spoiled, half-caste student decides to explode a bomb in school; a sexologist has to find a cure for a young boy who may have AIDS. -

“For a World Without Oppressors:” U.S. Anarchism from the Palmer

“For a World Without Oppressors:” U.S. Anarchism from the Palmer Raids to the Sixties by Andrew Cornell A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Social and Cultural Analysis Program in American Studies New York University January, 2011 _______________________ Andrew Ross © Andrew Cornell All Rights Reserved, 2011 “I am undertaking something which may turn out to be a resume of the English speaking anarchist movement in America and I am appalled at the little I know about it after my twenty years of association with anarchists both here and abroad.” -W.S. Van Valkenburgh, Letter to Agnes Inglis, 1932 “The difficulty in finding perspective is related to the general American lack of a historical consciousness…Many young white activists still act as though they have nothing to learn from their sisters and brothers who struggled before them.” -George Lakey, Strategy for a Living Revolution, 1971 “From the start, anarchism was an open political philosophy, always transforming itself in theory and practice…Yet when people are introduced to anarchism today, that openness, combined with a cultural propensity to forget the past, can make it seem a recent invention—without an elastic tradition, filled with debates, lessons, and experiments to build on.” -Cindy Milstein, Anarchism and Its Aspirations, 2010 “Librarians have an ‘academic’ sense, and can’t bare to throw anything away! Even things they don’t approve of. They acquire a historic sense. At the time a hand-bill may be very ‘bad’! But the following day it becomes ‘historic.’” -Agnes Inglis, Letter to Highlander Folk School, 1944 “To keep on repeating the same attempts without an intelligent appraisal of all the numerous failures in the past is not to uphold the right to experiment, but to insist upon one’s right to escape the hard facts of social struggle into the world of wishful belief. -

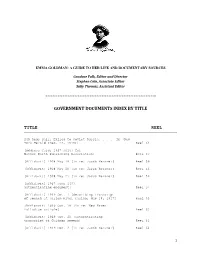

Government Documents Index by Title

EMMA GOLDMAN: A GUIDE TO HER LIFE AND DOCUMENTARY SOURCES Candace Falk, Editor and Director Stephen Cole, Associate Editor Sally Thomas, Assistant Editor GOVERNMENT DOCUMENTS INDEX BY TITLE TITLE REEL 249 Reds Sail, Exiled to Soviet Russia. In [New York Herald (Dec. 22, 1919)] Reel 64 [Address Card, 1917 July? for Mother Earth Publishing Association] Reel 57 [Affidavit] 1908 May 18 [in re: Jacob Kersner] Reel 56 [Affidavit] 1908 May 20 [in re: Jacob Kersner] Reel 56 [Affidavit] 1908 May 21 [in re: Jacob Kersner] Reel 56 [Affidavit] 1917 June 1[0? authenticating document] Reel 57 [Affidavit] 1919 Oct. 1 [describing transcript of speech at Harlem River Casino, May 18, 1917] Reel 63 [Affidavit] 1919 Oct. 18 [in re: New Haven Palladium article] Reel 63 [Affidavit] 1919 Oct. 20 [authenticating transcript of Goldman speech] Reel 63 [Affidavit] 1919 Dec. 2 [in re: Jacob Kersner] Reel 64 1 [Affidavit] 1920 Feb. 5 [in re: Abraham Schneider] Reel 65 [Affidavit] 1923 March 23 [giving Emma Goldman's birth date] Reel 65 [Affidavit] 1933 Dec. 26 [in support of motion for readmission to United States] Reel 66 [Affidavit? 1917? July? regarding California indictment of Alexander Berkman (excerpt?)] Reel 57 Affirms Sentence on Emma Goldman. In [New York Times (Jan. 15, 1918)] Reel 60 Against Draft Obstructors. In [Baltimore Sun (Jan. 15, 1918)] Reel 60 [Agent Report] In re: A.P. Olson (or Olsson)-- Anarchist and Radical, New York, 1918 Aug. 30 Reel 61 [Agent Report] In re: Abraham Schneider--I.W.W., St. Louis, Mo. [19]19 Oct. 14 Reel 63 [Agent Report In re:] Abraham Schneider, St. -

International Journal of Emerging Trends in Engineering And

International Journal of Emerging trends in Engineering and Development ISSN 2249-6149 Available online on http://www.rspublication.com/ijeted/ijeted_index.htm Issue 2, Vol.5 (July 2012) A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF PORTRAYAL OF WOMEN IN HENRIK IBSEN’S A DOLL’S HOUSE AND AUGUST STRINDBERG’S MISS JULIE RAMANDEEP MAHAL MAHARISHI MARKANDESHWAR UNIVERSITY MULLANA (AMBALA) __________________________________________________________________________________________ ABSTRACT Norwegian playwright and poet Henrik Ibsen was an acclaimed dramatist during his times. He had a great pride in his country Norway. In 1877 he was influenced by the social structure of his country. He wanted to extol the values of truth and freedom in his people with his works like The Pillars of the Society (1877) and then in 1879 A Doll’s House which questioned the suppressed role of women in the society. He is best known for creating female characters in dramas like Hedda Gabler (1890) and A Doll’s House. Nora the protagonist in the beginning of the play seems to be content with her life. She prances about and exhibits child like qualities. When Torvald enters the scene, Nora's childlike behavior becomes more patent. Torvald calls her pet names "little lark", "little squirrel", and "little miss extravagant". However Torvald‟s true character is revealed when he accuses Nora for the forgery and tries to disown her, unaware of the fact that she had forged the signature for his sake. His attitude suddenly changes when everything is sorted out. She decides to walk out of her marriage. Johan August Strindberg was a Swedish playwright, novelist and essayist. -

And They Called Them “Galleanisti”

And They Called Them “Galleanisti”: The Rise of the Cronaca Sovversiva and the Formation of America’s Most Infamous Anarchist Faction (1895-1912) A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Andrew Douglas Hoyt IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Advised by Donna Gabaccia June 2018 Andrew Douglas Hoyt Copyright © 2018 i Acknowledgments This dissertation was made possible thanks to the support of numerous institutions including: the University of Minnesota, the Claremont Graduate University, the Italian American Studies Association, the UNICO Foundation, the Istituto Italiano di Cultura negli Stati Uniti, the Council of American Overseas Research Centers, and the American Academy in Rome. I would also like to thank the many invaluable archives that I visited for research, particularly: the Immigration History Resource Center, the Archivio Centrale dello Stato, the Archivio Giuseppe Pinelli, the Biblioteca Libertaria Armando Borghi, the Archivio Famiglia Berneri – Aurelio Chessa, the Centre International de Recherches sur l’Anarchisme, the International Institute of Social History, the Emma Goldman Paper’s Project, the Boston Public Library, the Aldrich Public Library, the Vermont Historical Society, the U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, the Library of Congress, the Historic American Newspapers Project, and the National Digital Newspaper Program. Similarly, I owe a great debt of gratitude to tireless archivists whose work makes the writing of history