An Interactive Qualifying Project Report: Degree Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oriental Adventures James Wyatt

620_T12015 OrientalAdvCh1b.qxd 8/9/01 10:44 AM Page 2 ® ORIENTAL ADVENTURES JAMES WYATT EDITORS: GWENDOLYN F. M. KESTREL PLAYTESTERS: BILL E. ANDERSON, FRANK ARMENANTE, RICHARD BAKER, EIRIK BULL-HANSEN, ERIC CAGLE, BRAIN MICHELE CARTER CAMPBELL, JASON CARL, MICHELE CARTER, MAC CHAMBERS, TOM KRISTENSEN JENNIFER CLARKE WILKES, MONTE COOK , DANIEL COOPER, BRUCE R. CORDELL, LILY A. DOUGLAS, CHRISTIAN DUUS, TROY ADDITIONAL EDITING: DUANE MAXWELL D. ELLIS, ROBERT N. EMERSON, ANDREW FINCH , LEWIS A. FLEAK, HELGE FURUSETH, ROB HEINSOO, CORY J. HERNDON, MANAGING EDITOR: KIM MOHAN WILLIAM H. HEZELTINE, ROBERT HOBART, STEVE HORVATH, OLAV B. HOVET, TYLER T. HURST, RHONDA L. HUTCHESON, CREATIVE DIRECTOR: RICHARD BAKER JEFFREY IBACH, BRIAN JENKINS, GWENDOLYN F.M. KESTREL, TOM KRISTENSEN, CATIE A. MARTOLIN, DUANE MAXWELL, ART DIRECTOR: DAWN MURIN ANGEL LEIGH MCCOY, DANEEN MCDERMOTT, BRANDON H. MCKEE, ROBERT MOORE, DAVID NOONAN, SHERRY L. O’NEAL- GRAPHIC DESIGNER: CYNTHIA FLIEGE HANCOCK, TAMMY R. OVERSTREET, JOHN D. RATELIFF, RICH REDMAN, THOMAS REFSDAL, THOMAS M. REID, SEAN K COVER ARTIST: RAVEN MIMURA REYNOLDS, TIM RHOADES, MIKE SELINKER, JAMES B. SHARKEY, JR., STAN!, ED STARK, CHRISTIAN STENERUD, OWEN K.C. INTERIOR ARTISTS: MATT CAVOTTA STEPHENS, SCOTT B. THOMAS, CHERYL A. VANMATER-MINER, LARRY DIXON PHILIPS R. VANMATER-MINER, ALLEN WILKINS, PENNY WILLIAMS, SKIP WILLIAMS CRIS DORNAUS PRONUNCIATION HELP: DAVID MARTIN RON FOSTER, MOE MURAYAMA, CHRIS PASCUAL, STAN! RAVEN MIMURA ADDITIONAL THANKS: WAYNE REYNOLDS ED BOLME, ANDY HECKT, LUKE PETERSCHMIDT, REE SOESBEE, PAUL TIMM DARRELL RICHE RICHARD SARDINHA Dedication: To the people who have taught me about the cultures of Asia—Knight Biggerstaff, Paula Richman, and my father, RIAN NODDY B S David K. -

Maqueta Def. Nueva

L ARTE INTEGRADO EN LA BATALLA. ESTUDIO TECNOLÓGICO PREVIO A LA RESTAURACIÓN E DE CINCO ARMADURAS JAPONESAS DEL MUSEO DEL EJÉRCITO DE TOLEDO MARTA PLAZA BELTRÁN // JORGE RIVAS LÓPEZ1 Departamento de Pintura-Restauración. Universidad Complutense de Madrid Abstract: Throughout the eighteenth century the Chinoiserie style spread among the European courts. Based on Chinese and Japanese models, it was reflected both in painting and in architecture, as well as in decorative and textile arts. During this period many oriental items were imported from the Far East in order to decorate palaces and mansions. This was a determining factor for the increment of exotic art collecting, like Japanese lacquerware and Chinese porcelain. Samurai armours represent an exceptional example, which are veritable masterpieces made with remarkable complexity and using a great variety of materials. The main purpose of this article is to show the results prior to the intervention on the restoration of the collection of Japanese ar- mours belonging to the Army Museum in Toledo, Spain. In this way, a formal and symbolic analysis of the different elements involved in these sets will be exposed, as well as the most applied artistic technique to de- corate them: the Japanese lacquer. Key words: armour / samurai / artistic techniques / lacquer. Resumen: A lo largo del siglo XVIII la moda Chinoiserie se difundió entre las cortes europeas. Basada en mo- delos chinos y japoneses, la veremos reflejada tanto en la pintura como en la arquitectura, las artes decorativas o el arte textil. Durante este periodo se importaron numerosos objetos de Extremo Oriente con destino a los palacios y casas señoriales, factor determinante en el auge del coleccionismo de piezas de arte exótico, como las lacas japonesas y la porcelana china. -

Grandmaster Book of Ninja Training

The Grandmaster's Book of Ninja Training Dr Masaaki Hatsumi Translated by Chris, W. P. Reynolds Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Hatsumi, Masaaki, 1931- The grandmaster's book of ninja training / Masaaki Hatsumi. p. cm. Includes index. ISBN 0-8092-4629-5 (paper) 1. Hand-to-hand fighting, Oriental. 2. Ninjutsu. 3. Hatsumi, Masaaki, 1931- I. Title. U167.5.H3H358 1987 613.7'1—dc19 87-35221 CIP TRANSLATION NOTE Although some of the Japanese of these interviews was capably translated at the time it was given by Doron Navon, the entire text has been retranslated from the original. Unnecessary repetitions, inaudible phrases, etc., have been edited out. Dr. Hatsumi's manner of speak- ing is by no means always straightforward, and little attempt has been made to reproduce it, since it was felt that this would be too confusing and barely read- able. However, efforts have been made (including consultation with Hatsumi Sensei himself) to clarify the many points that required it. Only a few of his very frequently used interjected phrases (expressions Published by Contemporary Books A division of NTC/Contemporary Publishing Group, Inc. like "you see," "right?," etc.) have been retained, just 4255 West Touhy Avenue, Lincolnwood (Chicago), Illinois 60712-1975 U.S.A. for the sake of naturalness; and for the same reason, Copyright © 1988 by Masaaki Hatsumi some of the broken sentences and changes of direc- All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, tion characteristic of informal speech have been re- photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of tained, as long as the meaning is clear. -

Knights at the Museum Interactive Qualifying Project Submitted to the Faculty of the Worcester Polytechnic Institute in Fulfillment of the Requirements for Graduation

Knights! At the Museum Knights at the Museum Interactive Qualifying Project Submitted to the faculty of the Worcester Polytechnic Institute in fulfillment of the requirements for graduation. By: Jonathan Blythe, Thomas Cieslewski, Derek Johnson, Erich Weltsek Faculty Advisor: Jeffrey Forgeng JLS IQP 0073 March 6, 2015 1 Knights! At the Museum Contents Knights at the Museum .............................................................................................................................. 1 Authorship: .................................................................................................................................................. 5 Abstract: ...................................................................................................................................................... 6 Introduction ................................................................................................................................................. 7 Introduction to Metallurgy ...................................................................................................................... 12 “Bloomeries” ......................................................................................................................................... 13 The Blast Furnace ................................................................................................................................. 14 Techniques: Pattern-welding, Piling, and Quenching ...................................................................... -

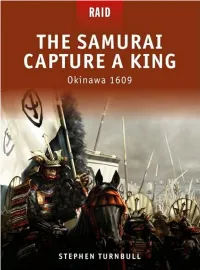

Raid 06, the Samurai Capture a King

THE SAMURAI CAPTURE A KING Okinawa 1609 STEPHEN TURNBULL First published in 2009 by Osprey Publishing THE WOODLAND TRUST Midland House, West Way, Botley, Oxford OX2 0PH, UK 443 Park Avenue South, New York, NY 10016, USA Osprey Publishing are supporting the Woodland Trust, the UK's leading E-mail: [email protected] woodland conservation charity, by funding the dedication of trees. © 2009 Osprey Publishing Limited ARTIST’S NOTE All rights reserved. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private Readers may care to note that the original paintings from which the study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright, colour plates of the figures, the ships and the battlescene in this book Designs and Patents Act, 1988, no part of this publication may be were prepared are available for private sale. All reproduction copyright reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by whatsoever is retained by the Publishers. All enquiries should be any means, electronic, electrical, chemical, mechanical, optical, addressed to: photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright owner. Enquiries should be addressed to the Publishers. Scorpio Gallery, PO Box 475, Hailsham, East Sussex, BN27 2SL, UK Print ISBN: 978 1 84603 442 8 The Publishers regret that they can enter into no correspondence upon PDF e-book ISBN: 978 1 84908 131 3 this matter. Page layout by: Bounford.com, Cambridge, UK Index by Peter Finn AUTHOR’S DEDICATION Typeset in Sabon Maps by Bounford.com To my two good friends and fellow scholars, Anthony Jenkins and Till Originated by PPS Grasmere Ltd, Leeds, UK Weber, without whose knowledge and support this book could not have Printed in China through Worldprint been written. -

I May Not Use the Japanese Terms for Everything in This Document, Or Spell Them the Way You Think They May Be Spelled

Please note: I may not use the Japanese terms for everything in this document, or spell them the way you think they may be spelled. Deal. Different sources happen. Sources will appear at the end of this document. Oh, and I hereby give permission for AEG and any forum moderators acting as representatives thereof to post this (unmodified and in its entirety, except as directed by me) as a reference document anywhere they need to do so, if they feel so inclined. SECTION ONE: INTRODUCTION AND ARMOR Armor exists in a constant state of flux, always attempting to protect the wearer against an ever-more lethal variety of battlefield threats. There are many reasons NOT to wear armor. It’s expensive. It’s high-maintenance. It is hot and smelly (sometimes to the point of causing heatstroke). It restricts your mobility. It dulls your senses and slows your reflexes. It’s never perfect, 100% protection. Therefore, it is reasonable to assume that if armor did not perform some valid battlefield function, people would not have worn it. People aren’t stupid. We may be more educated today, but people have a long history of seeing a problem, and then devoting all of their time and technological progress to that point in history finding a way to SOLVE that problem. Again, it stands to reason that, especially in a culture like that of Japan, where weaponry and armor simply did not evolve after reaching a certain level of technological development, there must be a rough balance between weaponry and protection. If armor was useless against battlefield weaponry, it would not have been worn. -

Asiatic Society of Japan

http://e-asia.uoregon.edu TRANSACTIONS OF THE ASIATIC SOCIETY OF JAPAN VOL XLVI.-PART II 1918 THE ASIATIC SOCIETY OF JAPAN, KEIOGIJIKU, MITA, TŌKYŌ AGENTS KELLY & WALSH, L'd., Yokohama, Shanghai, Hongkong Z. P. MARUYA Co., L'd., Tokyo KEGAN PAUL,TRUEBNER & Co., L'd., London TRANSACTIONS OF THE ASIATIC SOCIETY OF JAPAN VOL XLVI.-PART II 1918 THE ASIATIC SOCIETY OF JAPAN, KEIOGIJIKU, MITA, TŌKYŌ AGENTS KELLY & WALSH, L'd., Yokohama, Shanghai, Hongkong Z. P. MARUYA Co., L'd., Tokyo KEGAN PAUL,TRUEBNER & Co., L'd., London INTRODUCTION. Subject and Structure .---The Heike Monogatari, one of the masterpieces of Japanese literature, and also one of the main sources of the history of the Gempei period, is a poetic narrative of the fall of the Heike from the position of supremacy it had gained under Taira Kiyomori to almost complete destruction. The Heike, like the Genji, was a warrior clan, but had quickly lost its hardy simplicity under the influence of life in the Capital, and identified itself almost entirely with the effeminate Fujiwara Courtiers whose power it had usurped, so that the struggle between it and the Genji was really more one between courtiers and soldiers, between literary officials and military leaders. Historically this period stands between the Heian era of soft elegance and the Kamakura age of undiluted militarism. The Heike were largely a clan of emasculated Bushi, and their leader Kiyomori, though he obtained his supremacy by force of arms, assumed the role of Court Noble and strove to rule the country by the same device of making himself grandfather to the Emperor as the Fujiwara family had previously done. -

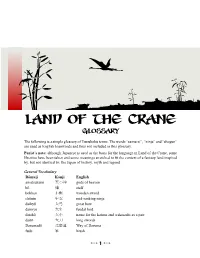

Land of the Crane Glossary

Land of the Crane Glossary The following is a simple glossary of Tsurukoku terms. The words “samurai”, “ninja” and “shogun” are used as English loanwords and thus not included in this glossary. Purist’s note: although Japanese is used as the basis for the language in Land of the Crane, some liberties have been taken and some meanings stretched to fit the context of a fantasy land inspired by, but not identical to, the Japan of history, myth and legend. General Vocabulary Rōmaji Kanji English amatsukami 天つ神 gods of heaven bō 棒 staff bokken 木剣 wooden sword chūnin 中忍 mid-ranking ninja daikyū 大弓 great bow daimyō 大名 feudal lord daishō 大小 name for the katana and wakizashi as a pair daitō 大刀 long swords Darumadō 達磨道 Way of Daruma fude 筆 brush Rōmaji Kanji English gaki 餓鬼 hungry ghost genin 下忍 low-ranking ninja geta 下駄 wooden clogs gō 業 karma hakama 袴 pleated divided skirt han 藩 fief hankyū 半弓 small bow hanyō 半妖 offspring of humans and supernatural creatures hara-ate 腹当 light armor haramaki 腹巻 medium armor harinezumi 猬 porcupine, hedgehog; porcupine race inkan 印鑑 personal seal irezumi 入墨 tattoo jashin 邪神 evil gods jō 杖 short staff jōnin 上忍 high-ranking ninja kama 鎌 sickle kami 神 gods, spirits, supernatural beings kami 紙 paper katana 刀 sword ki 気 spiritual or cosmic energy kidō 鬼道 Way of the Demons kimono 着物 kimono kitsune 狐 fox; fox people koku 石 unit of dry volume (about 180 liters or 5.11 bushels) kote 籠手 wrist and forearm guard kuge 公家 aristocracy, aristocrat kunai 苦無 small double-edged knife kuni 圀 country; also used to refer to large geographical -

Il Samurai. Da Guerriero a Icona

Il fiume di parole e d’immagini sul Giappone che si riversò a icona Da guerriero Il samurai. in Occidente dopo il 1860 lo configurò per sempre come l’idillica terra del Monte Fuji, coi laghi sereni punteggiati di vele, le geisha in pose seminude e gli indomabili samurai dalle misteriose armature. Il fascino che i guerrieri giapponesi e la loro filosofia di vita esercitarono sulla cultura del Novecento fu pari soltanto al desiderio di conoscere meglio la loro storia e i loro costumi, per svelare i segreti di una casta che prima Il samurai. di sconfiggere il nemico in battaglia aveva deciso, senza rinunciare ai piaceri della vita, di educare il corpo e la mente Da guerriero a icona a sconfiggere i propri limiti e le proprie paure, per raggiungere l’impalpabile essenza delle cose. a cura di Moira Luraschi 10 10 Antropunti Collana diretta da Francesco Paolo Campione Christian Kaufmann Antropunti € 32,00 Collana diretta da Francesco Paolo Campione Il samurai. Christian Kaufmann Da guerriero a icona La Collezione Morigi e altre recenti acquisizioni del MUSEC a cura di Antropunti Moira Luraschi 10 Sommario Note di trascrizione Prefazione 6 e altre avvertenze per la lettura Roberto Badaracco La trascrizione delle parole giapponesi Per la lettura delle parole trascritte ci si ba- segue il Sistema Hepburn modificato, fa- serà sulla fonologia italiana per le vocali, su Saggi I samurai. Guerrieri, politici, intellettuali 11 cendo eccezione per quei pochi casi in cui quella inglese per le consonanti. Si tenga Moira Luraschi un nome è entrato nell’uso corrente in una dunque presente che: ch è la c semiocclu- forma diversa (es. -

Nippon: Land of the Rising Sun Arms & Armour on Arms And

NIPPON: LAND OF THE RISING SUN ARMS & ARMOUR Written and Illustrated by Andrew R Fawcett for www.criticalhit.co.uk ON ARMS AND ARMOUR Armour worn in Nippon is completely different to that worn in the Old World. It is, on the whole, lighter and is heavily leather-based. Armour is restricted to the armouries of a clan and its usage depends upon the rank of the clansman; commoners do not wear armour other than, maybe, leather. Any rank of bushi (warrior) can wear armour although the high-ranking members of the clan will inevitably wear the more elaborate pieces. Furthermore, not every warrior in a clan is armed and armoured to the teeth, as some clans are richer or poorer than others and may not even have the necessary expertise in the making of some armour and weapons. The warriors of a clan are equipped according to what the clan has available or what they are left by their fathers; the latter case is the most common. Generally speaking, armour and weapons are usually owned by the family and handed down from father to son (such weapons and armour have pride of place in a bushi's house where an entire room is given over to them). Trade also does happen: a warrior may buy items from the clan's artisans but he should be wary of purchasing things which are inappropriate to his rank, i.e. a low-ranking bushi is not permitted to use a longbow. A warrior might trade with another warrior if he can afford it or he might even kill him for what he wears or carries. -

Low-Tech Armortm

LOADOUTS:TM LOW-TECH ARMORTM Written by DAN HOWARD Edited by JASON “PK” LEVINE Illustrated by DAVID DAY, DAN HOWARD, and SHANE L. JOHNSON GURPS System Design T STEVE JACKSON e23 Manager T STEVEN MARSH GURPS Line Editor T SEAN PUNCH Marketing Director T LEONARD BALSERA Managing Editor T PHILIP REED Director of Sales T ROSS JEPSON Assistant GURPS Line Editor T JASON “PK” LEVINE Prepress Checker T NIKKI VRTIS Production Artist & Indexer T NIKOLA VRTIS Page Design T PHIL REED and JUSTIN DE WITT Art Direction T MONICA STEPHENS GURPS FAQ Maintainer T VICKY “MOLOKH” KOLENKO Lead Playtester: Douglas H. Cole Playtesters: Roger Burton West, Nathan Joy, Rob Kamm, Stephen Money, David Nichols, and Antoni Ten Monrós GURPS, Warehouse 23, and the all-seeing pyramid are registered trademarks of Steve Jackson Games Incorporated. Pyramid, Loadouts, Low-Tech Armor, e23, and the names of all products published by Steve Jackson Games Incorporated are registered trademarks or trademarks of Steve Jackson Games Incorporated, or used under license. GURPS Loadouts: Low-Tech Armor is copyright © 2013 by Steve Jackson Games Incorporated. Some art © 2013 JupiterImages Corporation. All rights reserved. The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this material via the Internet or via any other means without the permission of the publisher is illegal, and punishable by law. Please purchase only authorized electronic editions, and do not participate in or encourage the electronic piracy of copyrighted materials. Your support of the author’s rights is appreciated. An e23 Sourcebook for GURPS® STEVE JACKSON GAMES Stock #37-1581 Version 1.0 – December 2013 ® CONTENTS INTRODUCTION . -

Escape from the Haunted Lands

Escape from the Haunted Lands By Uri Kurlianchik Plot by Charles Rice Artwork: Jason Walton, Joseph Wigfield Edited by Paul King Layout by David Jarvis Playtested by Paula Rice, Edward Lennon, Corey Hodges escape from the haunted lands “To ignore tradition is foolhardy; to anger the dead guerrilla tactics. Another important weapon in Haru’s by not providing for them tempts fate; to be in a place arsenal was his wife, Etsu, who was blessed with where others have died subjects you to forces beyond an ability to speak with the kami, the spirits of the your control. Avoidance, care, ritual, respect, tradition. earth and heaven, making the very land aid him in his These are your bywords.” righteous war. -The Rule of the Dead This war raged for more than a decade but just when it seemed that Shunichi was about to leave Welcome to legendary Japan, a land of unhappy ghosts Haru alone, disaster struck. and mischievous spirits, of cannibal demons and merciful kami. A place where honor is more important One of Haru’s senior retainers, a man so than gold and where one’s skill with sword and etiquette despicably treacherous that even his allies is the only thing that stands between glorious victory won’t speak his name, referring to him and shameful defeat. as Faithless instead, opened his trusting master’s castle gates to Shunichi’s host and “The Escape from the Haunted Lands” is the first thus brought about his master’s ultimate defeat. chapter in the “Haunted Lands” Adventure Path, a 10- As the Shunichi warriors swarmed in, slaughtering installment campaign designed to lead the characters the unprepared defenders, Etsu called down a terrible on a wonderful journey through the fabled lands of curse upon her husband’s land, merging it with Yomi, ancient Japan and latter Koryo in a quest to avenge the shadowy land of the dead, and making it useless for their master’s death and restore his son and heir to his Shunichi.