1:14-Cv-04361 Document #: 76 Filed: 07/17/14 Page 1 of 126 Pageid #:1233

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

U.S. Government Printing Office Style Manual, 2008

U.S. Government Printing Offi ce Style Manual An official guide to the form and style of Federal Government printing 2008 PPreliminary-CD.inddreliminary-CD.indd i 33/4/09/4/09 110:18:040:18:04 AAMM Production and Distribution Notes Th is publication was typeset electronically using Helvetica and Minion Pro typefaces. It was printed using vegetable oil-based ink on recycled paper containing 30% post consumer waste. Th e GPO Style Manual will be distributed to libraries in the Federal Depository Library Program. To fi nd a depository library near you, please go to the Federal depository library directory at http://catalog.gpo.gov/fdlpdir/public.jsp. Th e electronic text of this publication is available for public use free of charge at http://www.gpoaccess.gov/stylemanual/index.html. Use of ISBN Prefi x Th is is the offi cial U.S. Government edition of this publication and is herein identifi ed to certify its authenticity. ISBN 978–0–16–081813–4 is for U.S. Government Printing Offi ce offi cial editions only. Th e Superintendent of Documents of the U.S. Government Printing Offi ce requests that any re- printed edition be labeled clearly as a copy of the authentic work, and that a new ISBN be assigned. For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512-1800; DC area (202) 512-1800 Fax: (202) 512-2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402-0001 ISBN 978-0-16-081813-4 (CD) II PPreliminary-CD.inddreliminary-CD.indd iiii 33/4/09/4/09 110:18:050:18:05 AAMM THE UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE STYLE MANUAL IS PUBLISHED UNDER THE DIRECTION AND AUTHORITY OF THE PUBLIC PRINTER OF THE UNITED STATES Robert C. -

A Collection of Stories and Memories by Members of the United States Naval Academy Class of 1963

A Collection of Stories and Memories by Members of the United States Naval Academy Class of 1963 Compiled and Edited by Stephen Coester '63 Dedicated to the Twenty-Eight Classmates Who Died in the Line of Duty ............ 3 Vietnam Stories ...................................................................................................... 4 SHOT DOWN OVER NORTH VIETNAM by Jon Harris ......................................... 4 THE VOLUNTEER by Ray Heins ......................................................................... 5 Air Raid in the Tonkin Gulf by Ray Heins ......................................................... 16 Lost over Vietnam by Dick Jones ......................................................................... 23 Through the Looking Glass by Dave Moore ........................................................ 27 Service In The Field Artillery by Steve Jacoby ..................................................... 32 A Vietnam story from Peter Quinton .................................................................... 64 Mike Cronin, Exemplary Graduate by Dick Nelson '64 ........................................ 66 SUNK by Ray Heins ............................................................................................. 72 TRIDENTS in the Vietnam War by A. Scott Wilson ............................................. 76 Tale of Cubi Point and Olongapo City by Dick Jones ........................................ 102 Ken Sanger's Rescue by Ken Sanger ................................................................ 106 -

Good Reads for Fifth Graders

Fullerton Public Library Good Reads for Fifth Graders Items may be found in multiple locations. Check the catalog or ask a librarian for assistance. Adventure Barry, Dave. Peter and the Starcatchers. [AR BL 5.2, Pts. 13.0] Soon after Peter, an orphan, sets sail from England on the ship Never Land, he befriends and assists Molly, a young starcatcher, whose mission is to guard a trunk of magical stardust from a greedy pirate and the native inhabitants of a remote island. Black, Holly. Doll Bones. [AR BL 5.4, Pts. 7.0] Zach, Alice, and Poppy, friends from a Pennsylvania middle school who have long enjoyed acting out imaginary adventures with dolls and action figures, embark on a real-life quest to Ohio to bury a doll made from the ashes of a dead girl. Brown, Peter. The Wild Robot. [AR BL 5.1, Pts. 5.0] Roz the robot discovers that she is alone on a remote, wild island with no memory of where she is from or why she is there, and her only hope of survival is to try to learn about her new environment from the island's hostile inhabitants. George, Jean Craighead. My Side of the Mountain. [AR BL 5.2, Pts. 6.0] A boy relates his adventures during the year he spends living alone in the Catskill Mountains including his struggle for survival, his dependence on nature, his animal friends, and his ultimate realization that he needs human companionship. Healy, Christopher. A Dastardly Plot. (A Perilous Journey of Danger and Mayhem #1) [AR BL 5.2, Pts. -

Over 500 New and Used Boats YOUR DISCOUNT SOURCE! the BRANDS YOU WANT and TRUST in STOCK for LESS

Volume XIX No. 5 June 2008 Over 500 New and Used Boats YOUR DISCOUNT SOURCE! THE BRANDS YOU WANT AND TRUST IN STOCK FOR LESS Volume discounts available. # Dock & Anchor Line # Largest Samson Dealer Samson Yacht Braid # Yacht Braid # in 49 States! for all Applications # Custom Splicing # • Apex • Ultra-Lite # HUGE Selection # An example of our buying power • XLS Yacht Braid • Warpspeed Most orders ship the Over Half a Million 3/8” XLS Yacht Braid • Trophy Braid • LS Yacht Braid same day! Feet in Stock for • Ultratech • XLS Solid Color Immediate Delivery! Only 78¢/foot • Amsteel • Tech 12 • XLS Extra Your Discount ® Defender Boating Supply FREE 324 page Source for Catalog! www.defender.com 800-628-8225 • [email protected] Over 70 Years! Boating, The Way It Should Be! Over 650,000 BoatU.S. Members know how to stretch their boating dollars and get more out of boating. With access to discounts on boating equipment, time-saving services, information on boating safety and over 26 other benefits, our Members know it pays to belong! U Low-cost towing services and boat insurance U Subscription to BoatU.S. Magazine U Discounts on fuel, repairs and more at marinas nationwide U Earn a $10 reward certificate for every $250 spent at West Marine Stores With a BoatU.S. Membership, You Can Have it All! Call 800-395-2628 or visit BoatUS.com Mention Priority Code MAFT4T Join today for a special offer of just $19—that’s 25% off! Simply Smart™ Lake Minnetonka’s ROW Lake Minnetonka’s Premier Sailboat Marina Limited Slips Still Available! SAIL MOTOR Ask About Spring Get more fun from your tender. -

La Passion Est En Vous » Projet Handivoile Soutenu

«La Passion est en vous » projet handivoile soutenu par l’association Envol Océan Objectif Bol d’or mirabaud 2019 éric ERWAN Un défi unique Erwan Charamel, malvoyant et Éric Le Bouëdec, dyslexique se sont lancés un défi un peu fou : être le tout premier équipage handivoile sur un bâteau volant (flying phantom elite) à participer en juin 2019 au Bol d’Or Mirabaud en Suisse. Leur objectif : porter les couleurs du handicap dans le sport durant la plus grande régate du monde en bassin fermé. Un équipage hors norme Erwan et Éric se sont rencontrés en 2017, à ce moment là, Erwan cherchait un barreur pour participer à la National Hobie Cat Wild de La Rochelle. Leur duo voile sur un catamaran de sport a tout de suite fonctionné ! C’est le début de l’aventure pour Erwan et Éric. L’équipage handivoile est formé et décide de partir à la conquête de nouveaux défis ! C’est l’histoire de deux passionnés qui unissent leurs forces pour montrer que le handicap est compatible avec le sport et que rien n’est impossible ! ERWAN ÉRIC CHARAMEL LE BOUËDEC #malvoyant #dyslexique À l’âge de 7 ans, Erwan Charamel a perdu Pour Éric Le Bouëdec, le handicap ne doit pas quasiment la totalité de son acuité visuelle en à être un frein à la pratique du sport. Dyslexique, peine 6 mois - Maladie de Stargardt - ce qui ne son handicap est moins visible. Pourtant Éric a l’a pas empêché de se lancer dans de nombreux lui aussi dû s’adapter et développer sa capacité défis sportifs ! de visualisation : penser en image plutôt qu’en De l’optimist, au kitesurf en passant par le Flying mots. -

Exemplar Texts for Grades

COMMON CORE STATE STANDARDS FOR English Language Arts & Literacy in History/Social Studies, Science, and Technical Subjects _____ Appendix B: Text Exemplars and Sample Performance Tasks OREGON COMMON CORE STATE STANDARDS FOR English Language Arts & Literacy in History/Social Studies, Science, and Technical Subjects Exemplars of Reading Text Complexity, Quality, and Range & Sample Performance Tasks Related to Core Standards Selecting Text Exemplars The following text samples primarily serve to exemplify the level of complexity and quality that the Standards require all students in a given grade band to engage with. Additionally, they are suggestive of the breadth of texts that students should encounter in the text types required by the Standards. The choices should serve as useful guideposts in helping educators select texts of similar complexity, quality, and range for their own classrooms. They expressly do not represent a partial or complete reading list. The process of text selection was guided by the following criteria: Complexity. Appendix A describes in detail a three-part model of measuring text complexity based on qualitative and quantitative indices of inherent text difficulty balanced with educators’ professional judgment in matching readers and texts in light of particular tasks. In selecting texts to serve as exemplars, the work group began by soliciting contributions from teachers, educational leaders, and researchers who have experience working with students in the grades for which the texts have been selected. These contributors were asked to recommend texts that they or their colleagues have used successfully with students in a given grade band. The work group made final selections based in part on whether qualitative and quantitative measures indicated that the recommended texts were of sufficient complexity for the grade band. -

Centerboard Classes NAPY D-PN Wind HC

Centerboard Classes NAPY D-PN Wind HC For Handicap Range Code 0-1 2-3 4 5-9 14 (Int.) 14 85.3 86.9 85.4 84.2 84.1 29er 29 84.5 (85.8) 84.7 83.9 (78.9) 405 (Int.) 405 89.9 (89.2) 420 (Int. or Club) 420 97.6 103.4 100.0 95.0 90.8 470 (Int.) 470 86.3 91.4 88.4 85.0 82.1 49er (Int.) 49 68.2 69.6 505 (Int.) 505 79.8 82.1 80.9 79.6 78.0 A Scow A-SC 61.3 [63.2] 62.0 [56.0] Akroyd AKR 99.3 (97.7) 99.4 [102.8] Albacore (15') ALBA 90.3 94.5 92.5 88.7 85.8 Alpha ALPH 110.4 (105.5) 110.3 110.3 Alpha One ALPHO 89.5 90.3 90.0 [90.5] Alpha Pro ALPRO (97.3) (98.3) American 14.6 AM-146 96.1 96.5 American 16 AM-16 103.6 (110.2) 105.0 American 18 AM-18 [102.0] Apollo C/B (15'9") APOL 92.4 96.6 94.4 (90.0) (89.1) Aqua Finn AQFN 106.3 106.4 Arrow 15 ARO15 (96.7) (96.4) B14 B14 (81.0) (83.9) Bandit (Canadian) BNDT 98.2 (100.2) Bandit 15 BND15 97.9 100.7 98.8 96.7 [96.7] Bandit 17 BND17 (97.0) [101.6] (99.5) Banshee BNSH 93.7 95.9 94.5 92.5 [90.6] Barnegat 17 BG-17 100.3 100.9 Barnegat Bay Sneakbox B16F 110.6 110.5 [107.4] Barracuda BAR (102.0) (100.0) Beetle Cat (12'4", Cat Rig) BEE-C 120.6 (121.7) 119.5 118.8 Blue Jay BJ 108.6 110.1 109.5 107.2 (106.7) Bombardier 4.8 BOM4.8 94.9 [97.1] 96.1 Bonito BNTO 122.3 (128.5) (122.5) Boss w/spi BOS 74.5 75.1 Buccaneer 18' spi (SWN18) BCN 86.9 89.2 87.0 86.3 85.4 Butterfly BUT 108.3 110.1 109.4 106.9 106.7 Buzz BUZ 80.5 81.4 Byte BYTE 97.4 97.7 97.4 96.3 [95.3] Byte CII BYTE2 (91.4) [91.7] [91.6] [90.4] [89.6] C Scow C-SC 79.1 81.4 80.1 78.1 77.6 Canoe (Int.) I-CAN 79.1 [81.6] 79.4 (79.0) Canoe 4 Mtr 4-CAN 121.0 121.6 -

Tenpoint / What’S New

2020 PRODUCT CATALOG PERFECTION LIVES HERE™ TENPOINT / WHAT’S NEW NEW XTEND NEW TRIGGER LOCK-LATCH CRANK HANDLE • Locks trigger box in same position • Adjusts from 5" to 7.5" every time the bow is cocked • Reduces effort required • Improves down-range accuracy to cock the crossbow to by 48% only 5-pounds • Conveniently stores in the stock BUILT IN AMERICA BUILT 2 NEW ACUSLIDE NEW S1 TRIGGER • Silent Cocking • Advanced Roller Sear Design • Safe De-Cocking • 2-Stage Design • Zero-Creep • Crisp, 3.5-pound pull • Provides a level of accuracy never experienced NEW before with a crossbow THE INDUSTRY’S FIRST SILENT COCKING, SAFE DE-COCKING SYSTEM Forget holding buttons, using straps, and losing control while de-cocking. Meet TenPoint’s new ACUslide – The only safe and controlled crossbow de-cocking system on the market. Simply backwind the handle – stopping at any point without fear of damage, injury, or losing control. 2020 PRODUCT CATALOG TENPOINT / WHAT’S NEW NEW ROLLER SYSTEM 2 stainless steel rollers allow the trigger box to “glide” inside the barrel – creating an ultra-smooth feel during the silent cocking and controlled de-cocking process. ™ PERFECTION LIVES HERE 3 NEW MICRO-TRAC BARREL VECTOR QUAD™ CABLE SYSTEM “These are the most • Reduces string-to-rail contact by an • Utilizes 4 cables, instead of the traditional 2 accurate crossbows I have incredible 50% • Eliminates cam lean and generates straight ever shot. You won’t be • Increases down-range accuracy nock travel, leading to same hole down- disappointed.” • Provides the longest string life in the industry range accuracy • Unlike other crossbows on the market, allows for micro-tuning to ensure the highest level of accuracy IT TAKES A LATCH TO LOCK DOWN ACCURACY TRIGGER LOCK-LATCH Stainless steel latch locks the trigger box at full-draw – relieving the tension from the ACUslide unit and guaranteeing that your trigger box is in the same location on each shot, leading to 48% increased down-range accuracy. -

The Dictionary Legend

THE DICTIONARY The following list is a compilation of words and phrases that have been taken from a variety of sources that are utilized in the research and following of Street Gangs and Security Threat Groups. The information that is contained here is the most accurate and current that is presently available. If you are a recipient of this book, you are asked to review it and comment on its usefulness. If you have something that you feel should be included, please submit it so it may be added to future updates. Please note: the information here is to be used as an aid in the interpretation of Street Gangs and Security Threat Groups communication. Words and meanings change constantly. Compiled by the Woodman State Jail, Security Threat Group Office, and from information obtained from, but not limited to, the following: a) Texas Attorney General conference, October 1999 and 2003 b) Texas Department of Criminal Justice - Security Threat Group Officers c) California Department of Corrections d) Sacramento Intelligence Unit LEGEND: BOLD TYPE: Term or Phrase being used (Parenthesis): Used to show the possible origin of the term Meaning: Possible interpretation of the term PLEASE USE EXTREME CARE AND CAUTION IN THE DISPLAY AND USE OF THIS BOOK. DO NOT LEAVE IT WHERE IT CAN BE LOCATED, ACCESSED OR UTILIZED BY ANY UNAUTHORIZED PERSON. Revised: 25 August 2004 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS A: Pages 3-9 O: Pages 100-104 B: Pages 10-22 P: Pages 104-114 C: Pages 22-40 Q: Pages 114-115 D: Pages 40-46 R: Pages 115-122 E: Pages 46-51 S: Pages 122-136 F: Pages 51-58 T: Pages 136-146 G: Pages 58-64 U: Pages 146-148 H: Pages 64-70 V: Pages 148-150 I: Pages 70-73 W: Pages 150-155 J: Pages 73-76 X: Page 155 K: Pages 76-80 Y: Pages 155-156 L: Pages 80-87 Z: Page 157 M: Pages 87-96 #s: Pages 157-168 N: Pages 96-100 COMMENTS: When this “Dictionary” was first started, it was done primarily as an aid for the Security Threat Group Officers in the Texas Department of Criminal Justice (TDCJ). -

Air University Review

Í3M04 AIR UNIVERSITY mí reiview Irõm the êdltõFs aerie Potential authors frequently ask, “ What are you looking for?" Our first response is to refer them to the inside back cover, where the editorial policy of the journal is stated. To narrow that general guidance further, we are always looking for articles that examine the interrelationships between national objectives and developing aerospace capabilities, particularly in the light of technical advances by ourselves, our allies, and our adversaries. We do not limit our contents to matters of national policy; rather, we try to cover a broad spectrum of subjects of professional interest. New applications of improved hardware, management problems solved in innovative ways, technical breakthroughs described in lay language, human relations, and reviews of defense-related literature have always been pertinent. We are especially receptive to thoughtful and informed challenges to existing doctrine and practice. Contributors also express curiosity about the acceptance rate and if the Review pays for its articles. Acceptance rates vary, but an overall average would run close to 15 percent of the material submitted. Cash awards to eligible contributors currently vary between $80 and $150 for articles and major reviews (DOD employees are not considered eligible if they prepared the articles during normal duty time). Potential contributors should not be discouraged by the acceptance rate for major articles. Although we have a comfortable backlog of articles awaiting publication, we have an immediate and constant need for vignette and space-filler material. Flashes of humor or anecdotes that provide insight into leadership are particularly welcome. Our cover photo is of a Delta launch vehicle carrying the Intelsat III spacecraft. -

The Chinese People's Liberation Army in 2025

The Chinese People’s Liberation Army in 2025 The Chinese People’s The Chinese People’s Liberation Army in 2025 FOR THIS AND OTHER PUBLICATIONS, VISIT US AT http://www.carlisle.army.mil/ U.S. ARMY WAR COLLEGE David Lai Roy Kamphausen Editors: Editors: UNITED STATES Roy Kamphausen ARMY WAR COLLEGE PRESS David Lai This Publication SSI Website USAWC Website Carlisle Barracks, PA and The United States Army War College The United States Army War College educates and develops leaders for service at the strategic level while advancing knowledge in the global application of Landpower. The purpose of the United States Army War College is to produce graduates who are skilled critical thinkers and complex problem solvers. Concurrently, it is our duty to the U.S. Army to also act as a “think factory” for commanders and civilian leaders at the strategic level worldwide and routinely engage in discourse and debate concerning the role of ground forces in achieving national security objectives. The Strategic Studies Institute publishes national security and strategic research and analysis to influence policy debate and bridge the gap between military and academia. The Center for Strategic Leadership and Development CENTER for contributes to the education of world class senior STRATEGIC LEADERSHIP and DEVELOPMENT leaders, develops expert knowledge, and provides U.S. ARMY WAR COLLEGE solutions to strategic Army issues affecting the national security community. The Peacekeeping and Stability Operations Institute provides subject matter expertise, technical review, and writing expertise to agencies that develop stability operations concepts and doctrines. U.S. Army War College The Senior Leader Development and Resiliency program supports the United States Army War College’s lines of SLDR effort to educate strategic leaders and provide well-being Senior Leader Development and Resiliency education and support by developing self-awareness through leader feedback and leader resiliency. -

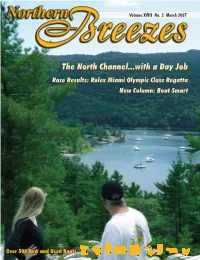

The North Channel...With a Day

Volume XVIII No. 2 March 2007 TheThe NorthNorth Channel...withChannel...with aa DayDay JobJob RaceRace Results:Results: RolexRolex MiamiMiami OlympicOlympic ClassClass RegattaRegatta NewNew Column:Column: BoatBoat SmartSmart Over 500 New and Used Boats Sail Repair Are you ready to sail in 2007? Drop your sail off now so you’re the first one on the lake this Spring! While you’re here, check out our new bag & gift ideas. 4495 Lake Ave South White Bear Lake, MN 55110 651.251.5494 Saillavieusa.com 2 Visit Northern Breezes Online @ www.sailingbreezes.com - March 2007 S A I L I N G S C H O O L Safe, fun, learning Learn to sail on Three Metro Lakes; Also Leech Lake, MN; Pewaukee Lake, WI; School of Lake Superior, Apostle Islands, Bayfield, WI; Lake Michigan; Caribbean Islands the Year Spring ashore courses: • Coastal Navigation • Radar for Mariners Gold Standard • Celestial Navigation • Weather and Seamanship • Instructor Training On-the-water courses weekends, week days, week day evenings starting May: • Basic Small Boat - $195 • Basic Keelboat - ASA Certification • Basic Coastal Cruising - ASA Certification • Coastal Navigation • Bareboat Charter - ASA Certification Lakes Michigan and Superior • Youth Camp • Advanced Coastal Cruising - ASA Offshore Course on Lakes Michigan and Superior • Vacation Courses: Basic Cruising and Bareboat Charter - 4-day live aboard courses on Lake Superior in the Beautiful Apostle Islands and Lake Michigan • Family Vacation Courses and Adventures From 3 To 5 Days • Cruising Multihull Aboard 38’ Catamaran • Celestial • Radar • Weather • Women’s Only Courses (All Levels): Call to set yours up or join others Newsletter • Rides • Call For Private, Flexible Schedule • Youth Sailing Camp (See P.