By Mike Finley 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

What I Learned Over Summer Vacation

Part of the Easy Peasy All-in-One Homeschool What I Learned Over Summer Vacation Balderdash and Other Stories By Lee Giles Copyright 2012 All Rights Reserved 1 Part of the Easy Peasy All-in-One Homeschool Balderdash School started back this week, and my teacher said we each had to take a turn telling the class what we did over the summer. Sarah and Michael, the twins, told all about their trip to space camp. They’re practically astronauts already. Randy told about skiing in Chile in July! I’ve never even been skiing in January. Julie flew in a hot air balloon, and Steve built a car, though I’m pretty sure his dad did most of the work. Their summers were all so exciting, so interesting, so unique, that I knew my summer vacation story had to be absolutely amazing. I wanted them to fall out of their seats for the sheer thrill of it! Do you want to hear my story? You might want to strap on a seat belt. Summer started out in the usual way with a bus ride home. I’m the first one on and the last one off, so it was just me and bus driver Fran left on the bus when a hail storm ripped through the sky like my big brother opening a box of marshmallow cereal. The hail stones were so big that they tore right through the bus hood and crushed the engine. Well, the bus wouldn’t go anywhere without an engine, but I got an idea. -

Arizona 500 2021 Final List of Songs

ARIZONA 500 2021 FINAL LIST OF SONGS # SONG ARTIST Run Time 1 SWEET EMOTION AEROSMITH 4:20 2 YOU SHOOK ME ALL NIGHT LONG AC/DC 3:28 3 BOHEMIAN RHAPSODY QUEEN 5:49 4 KASHMIR LED ZEPPELIN 8:23 5 I LOVE ROCK N' ROLL JOAN JETT AND THE BLACKHEARTS 2:52 6 HAVE YOU EVER SEEN THE RAIN? CREEDENCE CLEARWATER REVIVAL 2:34 7 THE HAPPIEST DAYS OF OUR LIVES/ANOTHER BRICK IN THE WALL PART TWO ANOTHER BRICK IN THE WALL PART TWO 5:35 8 WELCOME TO THE JUNGLE GUNS N' ROSES 4:23 9 ERUPTION/YOU REALLY GOT ME VAN HALEN 4:15 10 DREAMS FLEETWOOD MAC 4:10 11 CRAZY TRAIN OZZY OSBOURNE 4:42 12 MORE THAN A FEELING BOSTON 4:40 13 CARRY ON WAYWARD SON KANSAS 5:17 14 TAKE IT EASY EAGLES 3:25 15 PARANOID BLACK SABBATH 2:44 16 DON'T STOP BELIEVIN' JOURNEY 4:08 17 SWEET HOME ALABAMA LYNYRD SKYNYRD 4:38 18 STAIRWAY TO HEAVEN LED ZEPPELIN 7:58 19 ROCK YOU LIKE A HURRICANE SCORPIONS 4:09 20 WE WILL ROCK YOU/WE ARE THE CHAMPIONS QUEEN 4:58 21 IN THE AIR TONIGHT PHIL COLLINS 5:21 22 LIVE AND LET DIE PAUL MCCARTNEY AND WINGS 2:58 23 HIGHWAY TO HELL AC/DC 3:26 24 DREAM ON AEROSMITH 4:21 25 EDGE OF SEVENTEEN STEVIE NICKS 5:16 26 BLACK DOG LED ZEPPELIN 4:49 27 THE JOKER STEVE MILLER BAND 4:22 28 WHITE WEDDING BILLY IDOL 4:03 29 SYMPATHY FOR THE DEVIL ROLLING STONES 6:21 30 WALK THIS WAY AEROSMITH 3:34 31 HEARTBREAKER PAT BENATAR 3:25 32 COME TOGETHER BEATLES 4:06 33 BAD COMPANY BAD COMPANY 4:32 34 SWEET CHILD O' MINE GUNS N' ROSES 5:50 35 I WANT YOU TO WANT ME CHEAP TRICK 3:33 36 BARRACUDA HEART 4:20 37 COMFORTABLY NUMB PINK FLOYD 6:14 38 IMMIGRANT SONG LED ZEPPELIN 2:20 39 THE -

Tribute to the Cars to Appear at Hht

PRESS RELEASE – September 17, 2018 Susan Carrier (951) 551-5363 [email protected] TRIBUTE TO THE CARS TO APPEAR AT HHT On Saturday October 6th, the Historic Hemet Theatre will host a tribute to The Cars, a band that pioneered synthesizer pop music in the late 70's and early 80's. Performing the tribute will be Heartbeat City, a band that has recreated the look and sound of the Cars, dressing in the 80's style of the band and perfecting a sound that is amazingly close to the real thing! Although less well known than other classic bands, The Cars were quite successful in their day, including being named "Best New Artist" by Rolling Stone in 1978 and "Video of the Year" for "You Might Think" at the very first MTV Video Music Awards in 1984. Their debut album, The Cars, sold six million copies and appeared on the Billboard 200 album chart for 139 weeks. Robert Palmer, music critic for Rolling Stone, described the Cars' musical style by saying: "they have taken some important but disparate contemporary trends—punk minimalism, the labyrinthine synthesizer and guitar textures of art rock, the '50s rockabilly revival and the melodious terseness of power pop—and mixed them into a personal and appealing blend." The Cars most memorable hits include "My Best Friend's Girl," "Just What I Needed," "Who's Gonna Drive You Home Tonight?," and "Good Times Roll." The members of Heartbeat City are Phil Rowland (drums), Jamie Rio (lead vocals, guitar), Don E Sachs (Lead guitar, vocals), Andy Catt (bass, lead vocals), Mark Adame (keyboard, vocals). -

OAG Hearing on Interactions Between NYPD and the General Public Submitted Written Testimony

OAG Hearing on Interactions Between NYPD and the General Public Submitted Written Testimony Tahanie Aboushi | New York, New York I am counsel for Dounya Zayer, the protestor who was violently shoved by officer D’Andraia and observed by Commander Edelman. I would like to appear with Dounya to testify at this hearing and I will submit written testimony at a later time but well before the June 15th deadline. Thank you. Marissa Abrahams | South Beach Psychiatric Center | Brooklyn, New York As a nurse, it has been disturbing to see first-hand how few NYPD officers (present en masse at ALL peaceful protests) are wearing the face masks that we know are preventing the spread of COVID-19. Demonstrators are taking this extremely seriously and I saw NYPD literally laugh in the face of a protester who asked why they do not. It is negligent and a blatant provocation -especially in the context of the over-policing of Black and Latinx communities for social distancing violations. The complete disregard of the NYPD for the safety of the people they purportedly protect and serve, the active attacks with tear gas and pepper spray in the midst of a respiratory pandemic, is appalling and unacceptable. Aaron Abrams | Brooklyn, New York I will try to keep these testimonies as precise as possible since I know your office likely has hundreds, if not thousands to go through. Three separate occasions highlighted below: First Incident - May 30th - Brooklyn - peaceful protestors were walking from Prospect Park through the streets early in the day. At one point, police stopped to block the street and asked that we back up. -

Why Am I Doing This?

LISTEN TO ME, BABY BOB DYLAN 2008 by Olof Björner A SUMMARY OF RECORDING & CONCERT ACTIVITIES, NEW RELEASES, RECORDINGS & BOOKS. © 2011 by Olof Björner All Rights Reserved. This text may be reproduced, re-transmitted, redistributed and otherwise propagated at will, provided that this notice remains intact and in place. Listen To Me, Baby — Bob Dylan 2008 page 2 of 133 1 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................................................................. 4 2 2008 AT A GLANCE ............................................................................................................................................................. 4 3 THE 2008 CALENDAR ......................................................................................................................................................... 5 4 NEW RELEASES AND RECORDINGS ............................................................................................................................. 7 4.1 BOB DYLAN TRANSMISSIONS ............................................................................................................................................... 7 4.2 BOB DYLAN RE-TRANSMISSIONS ......................................................................................................................................... 7 4.3 BOB DYLAN LIVE TRANSMISSIONS ..................................................................................................................................... -

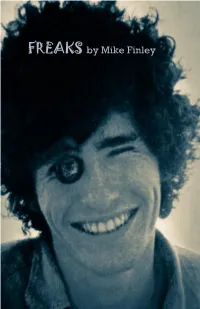

FREAKS by Mike Finley

FREAKS by Mike Finley ` 1 FREAKS A memoir of the 60s by Mike Finley Kraken Press, St. Paul © 2019 by Mike Finley ` 2 Note to Readers................................................................... 7 Vicklebar.............................................................................. 9 High on a Hilltop................................................................ 16 The Fake Riot......................................................................19 The Plot to Murder Me...................................................... 25 Dancing with Mister D....................................................... 33 Life Artists.......................................................................... 39 The Commons.................................................................... 44 Mail Order Ministry........................................................... 50 What We Lacked................................................................57 The Pickwick.......................................................................60 Good Soap..........................................................................64 The Creek Bed Glittered With Flecks Of Gold....................74 Trucking..............................................................................80 Big Bonito...........................................................................83 Deserters............................................................................90 Thompson's Chicken Ranch............................................... 99 Charles Manson and the Sons -

Read Book Just What I Needed Ebook Free Download

JUST WHAT I NEEDED PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Lorelei James | 368 pages | 02 Aug 2016 | Signet Book | 9780451477569 | English | United States Just What I Needed PDF Book Retrieved 19 September Funtime New Musical Express. Get promoted. Hello Again Thesaurus Entries near needed nectar nectars need needed needful needfulness needfuls See More Nearby Entries. Carlisle - 2m 4f - 2m 4f - 2m - 2m 1f - 2m 1f - 3m 2f - 2m 4f - 2m 4f View all races at Carlisle. Full Terms apply. Summary - Data does not include this horse 10 runs, 1 win 1 horse , 2 placed, 7 unplaced. We're gonna stop you right there Literally How to use a word that literally drives some pe The Cars. Bye Bye Love 5. Save Cancel. Down Boys. ATR Future Form Summary - Data does not include this horse 11 runs, 0 wins 0 horses , 2 placed, 9 unplaced Next time out 6 runs, 0 wins, 1 placed, 5 unplaced Class analysis 0 runs up in class, 0 wins, 0 placed, 0 unplaced Ratings check Highest winning OR: 0; Highest placed OR: 42 Index value from 6 horses. ATR Future Form Summary - Data does not include this horse 9 runs, 1 win 1 horse , 3 placed, 5 unplaced Next time out 4 runs, 1 win, 1 placed, 2 unplaced Class analysis 0 runs up in class, 0 wins, 0 placed, 0 unplaced Ratings check Highest winning OR: 57; Highest placed OR: 58 Index value from 4 horses. Save Word. Summary - Data does not include this horse 13 runs, 0 wins 0 horses , 2 placed, 11 unplaced. Next time out 6 runs, 0 wins, 1 placed, 5 unplaced. -

Red, Yellow, Blue Lauren Elizabeth Eyler University of South Carolina

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Theses and Dissertations 1-1-2013 Red, Yellow, Blue Lauren Elizabeth Eyler University of South Carolina Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd Part of the Creative Writing Commons Recommended Citation Eyler, L. E.(2013). Red, Yellow, Blue. (Master's thesis). Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/2315 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RED, YELLOW, BLUE by Lauren Eyler Bachelor of Arts Georgetown University, 2005 Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Fine Arts in Creative Writing College of Arts and Sciences University of South Carolina 2013 Accepted by: Elise Blackwell, Director of Thesis David Bajo, Reader John Muckelbauer, Reader Agnes Mueller, Reader Lacy Ford, Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies © Copyright by Lauren Eyler, 2013 All Rights Reserved. ii ABSTRACT Red, Yellow, Blue is a hybrid, metafictional novel/autobiography. The work explores the life of Ellis, Lotte, Diana John-John and Lauren as they wander through a variety of circumstances, which center on loss and grief. As the novel develops, the author loses control over her intentionality; the character’s she claims to know fuse together, leaving the reader to wonder if Lauren is synonymous with Ellis or if Diana is actually Lotte disguised by a signifier. Red, Yellow, Blue questions the author’s as well as the reader’s ability to understand the transformation that occurs in an individual during long periods of grief and anxiety. -

The Wombats' Daniel Haggis

OBMAGAZINE 2020 INSIDE... PARLOPHONE RECORDS' NICK BURGESS SARAH CREED ART CURATOR OF ONE OF LONDON’S MOST TALKED ABOUT MUSEUMS Playwright, author and television scriptwriter JONATHAN HARVEY Blue Coat Eco-Committee drives NEW GREEN AGENDA CHESS CLUB’S THE WOMBATS' RESURGENCE DANIEL HAGGIS NICK COWAN ON PERFORMING WITH PUTTING THE BLAZE THE ROLLING STONES INTO BLAZER CONTENTS CONTENTS KEEP IN TOUCH! We require your consent to communicate with you. 12 To view our Privacy Notice and communications consent form head over to our website. Once complete you will never miss an event invitation, e-newsletter or Old Blues magazine. www.bluecoatschoolliverpool. 38 HITTING36 THE RIGHT org.uk/old-blues/keep-touch 4 16 NOTE You can contact the Development 4 SCHOOL NEWS 22 AND THE AWARD 39 TECH STARTUP ZYNG Team directly at development-team @bluecoatschool.org.uk or on 7 SPORT REPORT GOES TO… 40 CALL THE BLUE COAT 0151 733 1407 ext. 207 9 CATCHING UP WITH… 23 ROBERT SKYNER MIDWIFE Don’t forget you can also keep in touch THE CLASS OF 2019 RAISES THE BAR 41 FLYING DOCTOR MATT with Blue Coat using our social media platforms: 10 TAKING TO THE STAGE 24 WOMEN IN STEAM IS READY FOR TAKE 12 INTERVIEW WITH… 26 INTRODUCING NICK OFF - AGAIN! /bluecoatschoololdblues JONATHAN HARVEY BURGESS, CO-PRESIDENT 42 5 MINUTES WITH… 14 IN BRIEF... OF PARLOPHONE RICHARD DOWNEY @LiverpoolBCS 16 EMPOWERING ART 28 NICK COWAN, PUTTING 43 REDMEN OF LIVERPOOL 18 POPPING IN TO SAY THE BLAZE INTO BLAZER www.linkedin.com/ 44 OLD BLUES AROUND groups/8153535 HELLO 30 OLD BLUES INSPIRING THE WORLD 19 5 MINUTES WITH… THE NEXT GENERATION 46 BE MINDFUL ABOUT Cover photo: Old Blue Daniel Haggis, GRAHAM JONES 32 PASS IT ON YOUR MENTAL HEALTH from the Class of 2002, and his band The Wombats perform at the 2019 19 DELVE INTO THE ARCHIVE 36 CLASS OF 1991: OUR 47 5 MINUTES WITH… Leeds Festival. -

![Bright (2017) Screenplay by Max Landis [Shooting Draft 02.29.2016]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9123/bright-2017-screenplay-by-max-landis-shooting-draft-02-29-2016-1729123.webp)

Bright (2017) Screenplay by Max Landis [Shooting Draft 02.29.2016]

BRIGHT Written by Max Landis 12/28/15 Current Revisions by David Ayer 02/29/16 red and blue lights flash in the dark rushing down streets you recognize a glimpse of magic, just a spark the monsters are familiar but the castles are amiss you've been here before but not quite like this For JRR Tolkien and David Ayer, who bring worlds to life. INT. WARD’S HOUSE - BEDROOM - DAY SCOTT WARD can’t sleep. He scowls in defiance at the golden midday sun scorching through the blinds. Plain but handsome, with an ‘I’m in charge here’ buzzcut. A thoughtful man, but no genius, he’s stymied by the daylight. We note the ANGRY BRUISING on his 200-pushups-a-day chest. Ward tries to fall back asleep. No dice. He shifts his weight and peels his Glock off his sweaty back. Sighs and starts counting the cracks in his bedroom ceiling... SMASH TO: EXT. LIQUOR STORE - WARD’S FLASHBACK - DAY A GANGBANGER in a black hoodie bursts out the door with a shotgun! WARD stands there in LAPD uniform. Reaches for his holster -- Breaks leather. Steps into a textbook shooting stance. Muzzle coming on target. Too Late... The GANGBANGER spins aims fires -- KABOOM! INT. WARD’S HOUSE - BEDROOM - DAY Ward gasps awake. His fingertips skim the ugly green and purple bruises on his chest. I’m still alive... INT. WARD’S HOUSE - KITCHEN - DAY Ward shuffles into the kitchen -- Sees SHERRI, his age, inspecting dishes in the sink, looking for the easiest one to wash. Pretty in a champagne room kind of way. -

The Haunted Continent and Andrew Bird's Apocrypha

University of Mississippi eGrove Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2013 Chasing That Ghost On Stage: The Haunted Continent And Andrew Bird's Apocrypha Mary Elizabeth Lasseter University of Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons Recommended Citation Lasseter, Mary Elizabeth, "Chasing That Ghost On Stage: The Haunted Continent And Andrew Bird's Apocrypha" (2013). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 1163. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd/1163 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CHASING THAT GHOST ON STAGE: THE HAUNTED CONTINENT AND ANDREW BIRD’S APOCRYPHA A Thesis presented in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Southern Studies The University of Mississippi by M.E. LASSETER May 2013 Copyright M.E. Lasseter 2013 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT This thesis traces the various physical and metaphorical journeys south of Chicago musician Andrew Bird. Using what historical record is publicly available, I examine Bird’s formal musical training. I then explore the years between 1995 and 2001, or what I call Bird’s period of apprenticeship. Next is an exploration of the canonical narratives surrounding the blues of the Mississippi Delta, especially the music of Charley Patton. When Andrew Bird encountered a canon, or dominant histories and meanings of Southern music that influence how musicians play and how audiences interpret that music, he began to react against that canon in his own compositions and performances. -

Personal Music Collection

Christopher Lee :: Personal Music Collection electricshockmusic.com :: Saturday, 25 September 2021 < Back Forward > Christopher Lee's Personal Music Collection | # | A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | | DVD Audio | DVD Video | COMPACT DISCS Artist Title Year Label Notes # Digitally 10CC 10cc 1973, 2007 ZT's/Cherry Red Remastered UK import 4-CD Boxed Set 10CC Before During After: The Story Of 10cc 2017 UMC Netherlands import 10CC I'm Not In Love: The Essential 10cc 2016 Spectrum UK import Digitally 10CC The Original Soundtrack 1975, 1997 Mercury Remastered UK import Digitally Remastered 10CC The Very Best Of 10cc 1997 Mercury Australian import 80's Symphonic 2018 Rhino THE 1975 A Brief Inquiry Into Online Relationships 2018 Dirty Hit/Polydor UK import I Like It When You Sleep, For You Are So Beautiful THE 1975 2016 Dirty Hit/Interscope Yet So Unaware Of It THE 1975 Notes On A Conditional Form 2020 Dirty Hit/Interscope THE 1975 The 1975 2013 Dirty Hit/Polydor UK import {Return to Top} A A-HA 25 2010 Warner Bros./Rhino UK import A-HA Analogue 2005 Polydor Thailand import Deluxe Fanbox Edition A-HA Cast In Steel 2015 We Love Music/Polydor Boxed Set German import A-HA East Of The Sun West Of The Moon 1990 Warner Bros. German import Digitally Remastered A-HA East Of The Sun West Of The Moon 1990, 2015 Warner Bros./Rhino 2-CD/1-DVD Edition UK import 2-CD/1-DVD Ending On A High Note: The Final Concert Live At A-HA 2011 Universal Music Deluxe Edition Oslo Spektrum German import A-HA Foot Of The Mountain 2009 Universal Music German import A-HA Hunting High And Low 1985 Reprise Digitally Remastered A-HA Hunting High And Low 1985, 2010 Warner Bros./Rhino 2-CD Edition UK import Digitally Remastered Hunting High And Low: 30th Anniversary Deluxe A-HA 1985, 2015 Warner Bros./Rhino 4-CD/1-DVD Edition Boxed Set German import A-HA Lifelines 2002 WEA German import Digitally Remastered A-HA Lifelines 2002, 2019 Warner Bros./Rhino 2-CD Edition UK import A-HA Memorial Beach 1993 Warner Bros.